Where Did Japan Begin? Awaji Island and the Origins of Yamato

Japanese Capitals

Then history begins to quicken. The Sengoku period brings burning castles and the siege of Shirasu by Hideyoshi’s army. In the peaceful Edo era, the Awaji Ningyō Jōruri puppet theatre flourishes — its dolls larger and more lifelike than anywhere else — and the fragrant smoke of incense produced here has for centuries filled temples across Japan. In the 20th century, the island suffers the catastrophe of a great earthquake, yet visions of the future are born: the monumental Akashi-Kaikyō Bridge, a masterpiece of engineering, and Tadao Andō’s Yumebutai — gardens and terraces rising from the ruins of an old quarry. Today, let us uncover the story of Awaji — an island that remembers the primal dawn and the gods, the wars of aristocracy and samurai, the blossoming of culture, art, and dreams of the future.

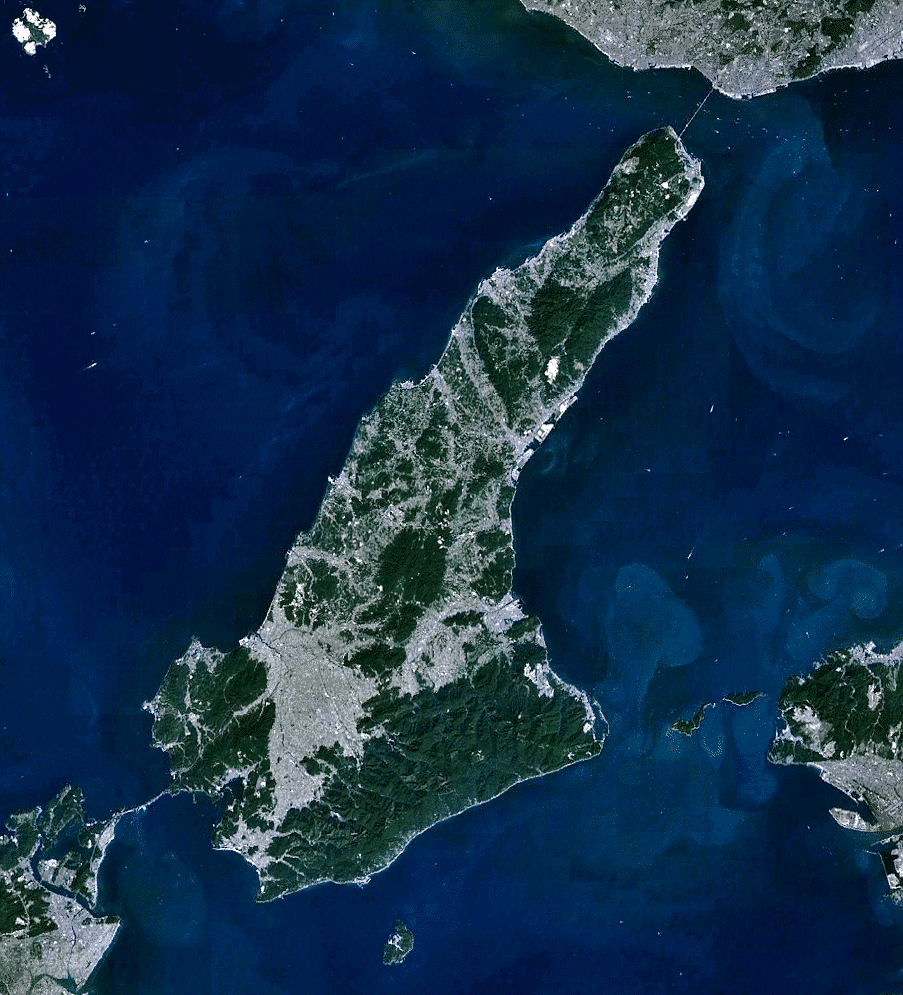

The View

Awaji is not a place that can be easily described in a single word. It is a gateway between Honshū and Shikoku, but also a point where myth meets the present. Steel bridges and geometric gardens stand side by side with sacred rocks, and every breath of sea wind seems to carry echoes of stories from millennia past. This is the island where Japan began. And we can still see it, still touch it.

Awaji — “the first island” of mythical Japan

Sources

Working with these sources is not without risk. They are not “historical” records in the modern sense. Rather, they are sacred geographies interwoven with the political interests of their time: every toponym, every rock, every ocean whirlpool becomes a point where divinity descends to earth. In this narrative, Awaji is not just an island — it is a threshold, a place where the world emerges from chaos, and at the same time a symbolic gate between the realm of the gods and the Japan of men.

The Birth of the Japanese Archipelago

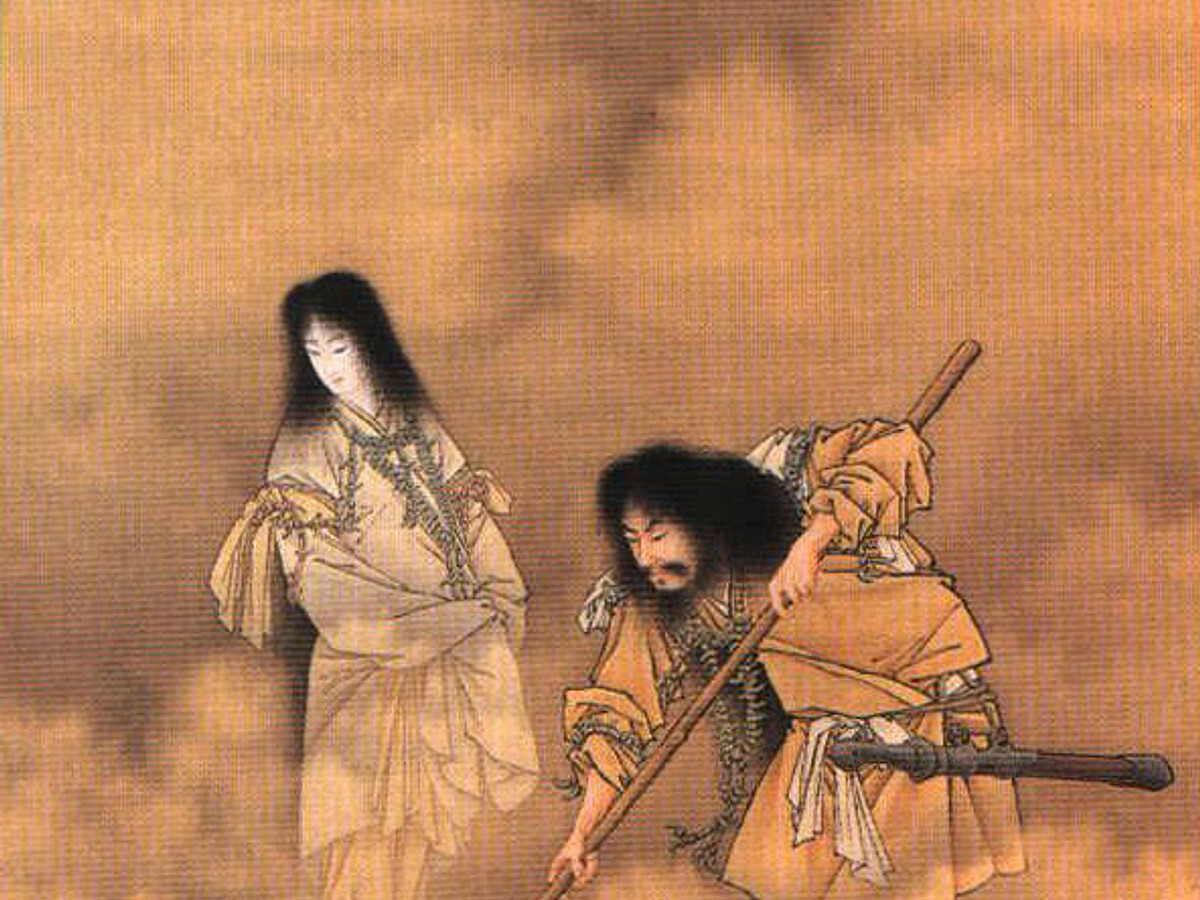

Standing upon the Heavenly Floating Bridge (Ame no ukihashi), they plunged into the shapeless ocean mass a spear called Ame-no-nuboko — the “Heavenly Spear of Jewels.” When they lifted it back up, the drops of saltwater dripping from its blade solidified and formed the first island. That island was Awaji, also known as Onogoroshima (自凝島, “The Island of Self-Condensation”).

It is worth noting the meaning of the name Awaji itself. It most likely derives from the words awa (粟, “millet” or “foam”) and ji (路, “road”), which allows it to be read as “the road of foam” or “the passage between the waves” — describing the island as a gateway between seas, but also as a threshold between the world of chaos and the world of form.

Onogoroshima

The first is the Onokoro Island Shrine (自凝島神社) in Minamiawaji, a sanctuary perched on a hill overlooking the turquoise waters of the Seto Inland Sea. Its monumental torii gate, lacquered in deep cinnabar, rises 21.7 meters high and is counted among the “Three Great Torii of Japan.” According to legend, it was here that Izanagi and Izanami descended to earth and performed their marriage ritual, circling together around a sacred pillar standing at the center of the island.

The absence of a single “true” Onogoro speaks volumes about how the Japanese understand sacred space. Unlike in Western traditions, here sacredness is diffuse: the myth does not confine itself to a single place but lives across many locations at once, like an echo carried by the sea.

The Myth of Awaji

For scholars of religion, Awaji represents a classic example of a liminal space: a threshold between form and formlessness, life and death, heaven and earth. Here, water is both chaos and purification; rock is both origin and the pillar of the cosmos; and every geographic name is a code preserving the memory of beginnings.

Izanagi Jingū — the Founding Cult

Izanagi Jingū is also one of the few places in Japan where rituals related to the creation of the world are still performed. Every spring, the Onokorojinja Reitaisai festival takes place, during which the people of Awaji symbolically recreate the act of creation by circling a pillar driven into the earth. It is theatre, religion, and memory intertwined — living proof that, for the island’s inhabitants, the myth is still, in some sense, the present.

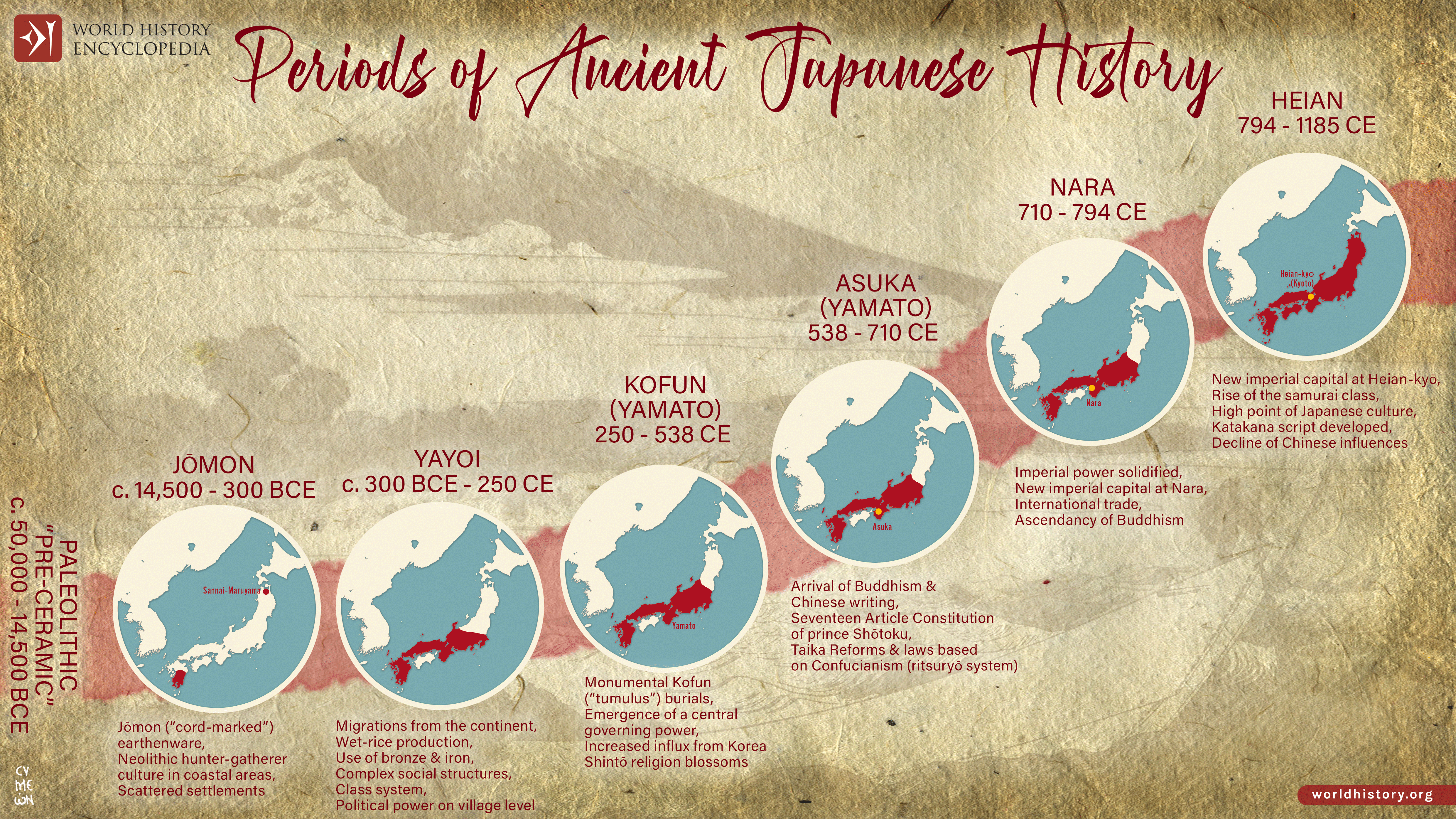

Archaeology: From the Jōmon to the Kofun Period

Awaji is often called the “first island,” the place where — according to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki — the gods first set foot upon the earth. Yet long before the myths were born, long before words were written about Izanami and Izanagi, there was human presence here — real, tangible, preserved in the soil’s layers. The archaeology of Awaji is like a slow unveiling of the island’s quiet memory — the same memory that imagination once clothed in divine stories. It is here, between sea and forest, that archaeologists search for traces of Japan’s earliest inhabitants, reconstructing their daily lives, rituals, and trade networks.

Jōmon Period (14,000 – 300 BCE)

Some of these findings can now be seen at the Hyōgo Prefectural Museum of Archaeology in Harima, where a dedicated exhibition explores Awaji’s role in the earliest settlement networks of the region. Archaeologists emphasize that the island was far more than a peripheral outpost: it served as a “maritime bridge” linking western Japan with eastern Shikoku, playing a vital role in the spread of technology and culture.

Yayoi (300 BCE – 300 CE)

These findings have completely transformed our understanding of Awaji’s role during the Yayoi period. Previously, scholars believed that iron production was concentrated in northern Kyūshū and western Honshū, but Awaji has proven to have been a key hub in the network of smelting and metal distribution across the Seto Inland Sea basin. Archaeologist Sakai Toshihiko, who led the excavations, emphasizes that thanks to Gossa, “Awaji became one of the most important technological centers of protohistoric Japan.”

In 2012, the site was granted the status of a National Historic Site (国宝, kokuhō), and in 2025, plans are underway to expand its protected area. Importantly, isotopic analysis of the iron ore indicates that it originated from various parts of the archipelago, proving the existence of an extensive exchange network linking Kyūshū, Shikoku, and Kansai. It is likely that the local rulers of Awaji — even before the emergence of the first Yamato states — held a strategic position in controlling the flow of metal and technology.

Kofun (c. 300 – 600 CE)

Near the Kifune Jinja sanctuary (貴船神社遺跡), archaeologists discovered traces of intensive salt production from this period: remnants of furnaces, fragments of ceramic vessels used for evaporating brine, and shards of large storage amphorae. Salt production was vital to the development of early state structures, enabling large-scale preservation and transport of food, and Awaji — surrounded by the sea — was perfectly positioned for such activity.

Numerous burial mounds from this era have also been preserved on the island. Though most are now modest in size, archaeologists believe that by the 5th century, parts of Awaji’s coastline served as a hinterland for Yamato elites. A powerful symbol of this connection is the mausoleum of Emperor Junnin (淳仁天皇陵), who reigned from 758 to 764 CE. After the rebellion of Fujiwara no Nakamaro, the emperor was exiled to Awaji, where he died in 765. Today, his tomb — officially recognized by the Imperial Household Agency (Kunai-chō) as an imperial mausoleum (misasagi, 御陵) — stands as a reminder that by the 8th century, Awaji was no longer merely a peripheral island but a place intimately connected to the very center of Japanese power.

Awaji During the Classical State Era (Nara / Heian)

During the period when Japan was undergoing a profound transformation toward a centralized state modeled after the Chinese ritsuryō (律令) system, Awaji ceased to be merely the place of mythical beginnings. It became part of the newly emerging political order, yet at the same time retained its aura of the sacred — a liminal space, separating the “center” from the “periphery.” It is within this duality — combining administration, religion, literature, and exile — that Awaji functioned for centuries, earning a reputation as an exceptional island.

The Ritsuryō Administration

The Ritsuryō Administration

In 701, with the enactment of the Taihō Code (大宝律令), Japan adopted a system of governance inspired by China’s Tang dynasty. The entire country was divided into provinces (kuni, 国), districts (gun, 郡), and villages (sato, 里). At this time, Awaji became 淡路国 (Awaji no kuni) — the “land of gentle waters” — and was incorporated into the larger administrative unit of Kinai (畿内), which encompassed the territories closest to the imperial court in Nara.

The provincial capital was located at the administrative headquarters known as 国府 (kokufu), situated in what is today Mihara (三原). Here stood the kokuga (国衙) — a complex of provincial government offices where the governor (kokushi, 国司) exercised authority, oversaw tax collection, and managed transportation networks and ferry routes. Beside the kokuga was the gunge (郡家), the district office combining administrative and logistical functions. Archaeologists from Kyoto University have uncovered the remains of large, rectangular buildings in Mihara whose layouts reflect continental architectural influences — central courtyards and symmetrical plans characteristic of the Nara period.

Yet the most important sanctuary remained Izanagi Jingū, regarded as the ichinomiya — the highest-ranking shrine — of the province. According to legend, it was here that the god Izanagi spent the final years of his life after descending into Yomi, the land of the dead. Already in the Nara and Heian periods, Izanagi Jingū functioned as a pilgrimage center, and its cult was directly tied to imperial genealogy — for the court in Nara (we dedicated an article to the history of this city here: The City of Nara – a Geometrically and Spiritually Designed Metropolis of Ancient Japan Long Before the Samurai) and later in Heian, it served as confirmation of the divine lineage of the ruling dynasty.

Thus, although small in size, Awaji played a role within the ritsuryō state structure far greater than its geographic scale would suggest. It was simultaneously a peripheral province and a sacred site, a space where administration, religion, and myth intertwined in a way that remains almost tangible.

How Was Awaji Portrayed in the Heian Period?

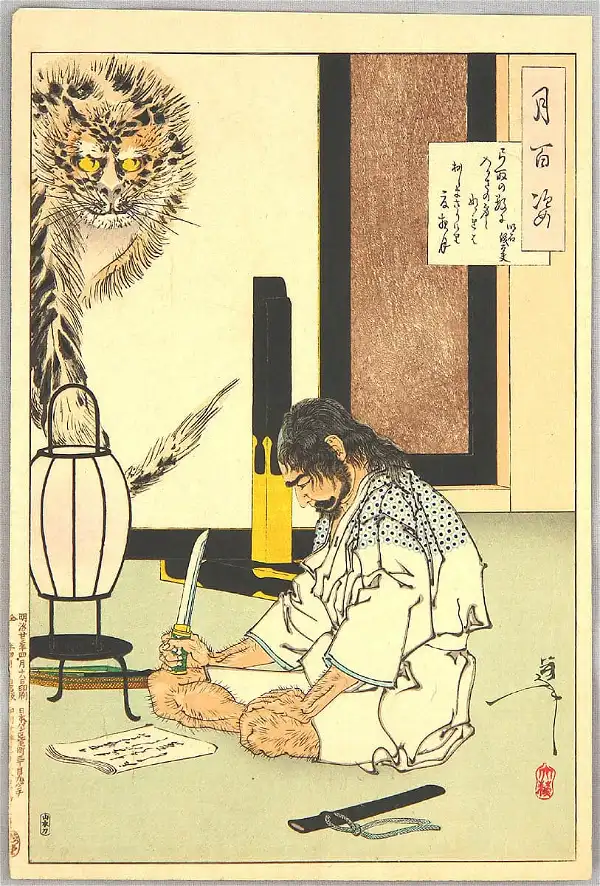

In Hyakunin Isshu — the classical anthology of one hundred poems compiled by Fujiwara no Teika in the 13th century — poem number 78, by Minamoto no Kanemasa (源兼昌), evokes Awaji in a tone suffused with melancholy:

淡路島 / かよふ千鳥の / 鳴く声に / 幾夜寝覚めぬ / 須磨の関守

Awajishima kayo-fuchidori no naku koe ni / ikuyo nezamenu Suma no sekimori

"To Awaji Island

the plovers fly and return —

and I, the watchman of Suma,

wake restless through endless nights,

still hearing their cries in the dark."

This poem is exquisitely subtle, yet filled with longing. The watchman of Suma, separated from the imperial world, hears the voices of the birds flying over Awaji — the sounds of nature become echoes of his exile, symbols of isolation and solitude. Heian poetry abounds in such connections between topography and the state of the soul, and Awaji — lying on the threshold between the Seto Inland Sea and the open ocean — was particularly suited to projections of melancholy.

This motif is further developed by Murasaki Shikibu in her masterpiece Genji monogatari. In the chapter titled Suma, Prince Genji, exiled from Kyoto, finds himself on the coast opposite Awaji. He gazes at the island’s rocks, listens to the waves, and becomes the central figure in one of the most celebrated scenes of contemplative impermanence in Japanese literature. The view of Awaji becomes a landscape of emotion, a space where nature, distance, and exile merge into a single reflection on the transience of life.

An Island on the Frontier in Times of War (Kamakura – Sengoku)

In the latter half of the 15th century, eastern Japan plunged into chaos, while new powers rose in the west. One of these was the Miyoshi clan, who initially served as vassals of the Hosokawa. The Miyoshi grew increasingly ambitious as they amassed wealth from trade across the Inland Sea and gained control over the routes linking Awa, Sanuki, and Awaji. By the mid-16th century, during Japan’s period of fragmentation, the Miyoshi emerged as regional hegemons. For a brief moment, it seemed that Awaji would become an integral part of their miniature “maritime principality” — its islands, ports, and castles forming a new map of power.

The Early Modern Period (Edo)

With the fall of the Toyotomi and the victory of the Tokugawa at the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), Awaji Island, like the rest of Japan, entered a period of long-lasting stability. These lands came under the rule of the Hachisuka clan, the daimyō of Tokushima, who in 1615 were granted jurisdiction over both the province of Awa on Shikoku and the entirety of Awaji Island. This was a deliberate gesture by the Tokugawa: entrusting a strategically important coastal territory to a family loyal to Edo.

However, just a few decades later, in 1615, the ikkoku ichijō rei (一国一城令, more about Tokugawa bakufu laws here: What to Do with a Society of Samurai Who Only Know War and Death in Times of Peace? - The Clever Ideas of the Tokugawa Shoguns) — the “one castle per domain edict” — was issued, forcing the Inada to dismantle most of their fortifications. Sumoto-jō was partially deconstructed, and its vast stone foundations have survived as an almost archaeological relic of the Tokugawa system of governance.

The Edo period was, therefore, a time of apparent stillness for Awaji. Under the rule of the Hachisuka and Inada families, the island was not a site of great battles or political upheaval, but rather a space of cultural refinement: puppet theatre reached unparalleled mastery, incense from Awaji perfumed palaces and temples across Japan, and local fish and rice made their way to the dining tables of Edo and Osaka. In the shadow of castles and rice paddies, Awaji’s culture was born — a culture of delicate aromas, full of stories and rituals that continue to live on this “first island” of Japan.

Modernity and Turbulent Centuries: Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa

Awaji, an island that for centuries embodied myth, art, and commerce, entered the modern era abruptly and violently. The turn of the 19th and 20th centuries marked not only the end of the feudal order but also the beginning of an entirely new political, social, and economic landscape. The Meiji Restoration, industrial growth, the advent of railways, and finally the devastation of a massive earthquake — all left marks on the island that remain visible today.

Meiji — The Inada Incident (1870)

The Inada clan, which had governed the island since the 17th century on behalf of the Hachisuka daimyō of Tokushima, refused to submit to the new order. Facing the planned integration of all domains into the imperial administrative system, they demanded that Awaji remain under their control — seeking to preserve partial autonomy and their traditional privileges. When tensions between the Inada and Hachisuka escalated, armed clashes erupted between their supporters on the island.

The new government in Tokyo could not tolerate a rebellion that threatened to set a precedent for other regions. Imperial troops were dispatched and swiftly suppressed the unrest. Several leaders of the rebellion were sentenced to perform compulsory seppuku — the last documented cases of state-ordered ritual suicide in Japanese history. This event marked the symbolic end of the feudal era on Awaji. From then on, the island became an integral part of the modern nation-state rather than the private fief of an old clan.

Industrialization and Disaster — The 20th Century

In 1922, the Awaji Island Railway (Awaji Tetsudō, 淡路鉄道) opened, connecting the island’s north and south between Sumoto and Iwaya. This was a breakthrough moment: thanks to the railway, transporting rice, incense, textiles, and fish became faster and more profitable. Along the coast, trading ports flourished, facilitating commerce with Osaka, Kobe, Tokushima, and Takamatsu.

Small-scale industry also developed, particularly in the textile sector. Family-run workshops wove cotton fabrics and produced fishing nets, while some areas underwent land reclamation for new rice fields. Despite these developments, Awaji’s economy remained more artisanal and traditional than that of the great industrial centers of Kansai. The railway, which had so dramatically reshaped the island, was eventually shut down in 1966 due to the rise of automobile transport — but its former line still lives on in the memory of older residents as a symbol of “modernity that came too late.”

The events of 1995 became a turning point not only for Awaji but for all of Japan: they led to a sweeping revision of safety policies, reinforced building standards, and strengthened community bonds on the island. Today, the “Hanshin/Awaji Daishinsai” stands as a symbol of both tragedy and resilience, a reminder that life on the edge of tectonic plates will always be a fragile compromise between humanity and nature.

Awaji in the 21st Century

At the turn of the 21st century, Awaji ceased to be an “island” in the traditional sense. In 1998, the Akashi–Kaikyō Bridge opened — the largest and most spectacular construction project in the island’s history. Spanning the waters of the Akashi Strait, it connects Awaji to Kobe on Honshū. The bridge measures 3,911 meters in total length, with its central span stretching an unprecedented 1,991 meters — for many years, it held the world record in this category, surpassed today only by Turkey’s 1915 Çanakkale Bridge. Decades in the making, the project was both an engineering challenge and a symbolic gesture: uniting two lands separated by the sea for millennia.

The bridge carries with it an anecdote that still brings a smile. On January 17, 1995, the Hanshin–Awaji earthquake tore open the earth along the Nojima Fault, shifting the island by several dozen centimeters. When engineers began assembling the bridge’s main structural elements, they discovered that its planned length had “grown” by a full meter. Adjustments had to be made, and the event became a symbol of the paradoxical interplay between nature and technology: the land itself can change faster than humans can map it.

This new accessibility transformed the island’s identity. Once, reaching Awaji required a ferry journey — slow and weather-dependent. Today, it is less than a 30-minute drive from Kobe. Tourism has flourished: the island has become a popular weekend destination, especially for residents of the Kansai region. Modern resorts and conference centers have emerged, but one of the most symbolic undertakings was the vision of architect Tadao Andō. On the site of an abandoned quarry, he created Awaji Yumebutai (淡路夢舞台), a monumental complex combining a hotel, terraced gardens, conference halls, and public spaces. This is a place marked by history: massive stone blocks extracted from here were used to construct the iconic Akashi–Kaikyō Bridge, and today the space has been transformed into a manifesto of renewal, modern design, and dialogue between nature and architecture.

Modern Awaji is a place of paradoxes: an island that has lost its isolation yet retains a distinct identity. Here, ancient myths, monasteries, and shrines coexist with the futuristic symbols of the 21st century. It is a place where you can still stand on the shores of Nushima, believed by many to be the legendary Onogoroshima, and just hours later stroll through Andō’s terraced gardens while admiring the bridge that redefined the region’s geography. In this way, Awaji becomes not only a bridge between Honshū and Shikoku but also a bridge between Japan’s past and its future.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

To See One’s Own Path Through the “Heavenly Bridge” in the Japanese Sumi-e Art of Master Sesshu

In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun – The Story of Amaterasu

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Ritsuryō Administration

The Ritsuryō Administration