Japanese Pirates of the Murakami Clan: Educated Samurai, Bandits, Entrepreneurs, Poets – Who Were They?

The Surprising Pirates of Sengoku Japan

Today, we will explore this extraordinary history. The kaizoku (Japanese pirates) of the Murakami clan were not only guardians and sailors but also poets who composed renga and tanka. We will journey to the turbulent waters of the Seto Inland Sea to uncover their fortresses, understand how they controlled trade, and form our own opinions—were they pirates, guardians, or entrepreneurs?

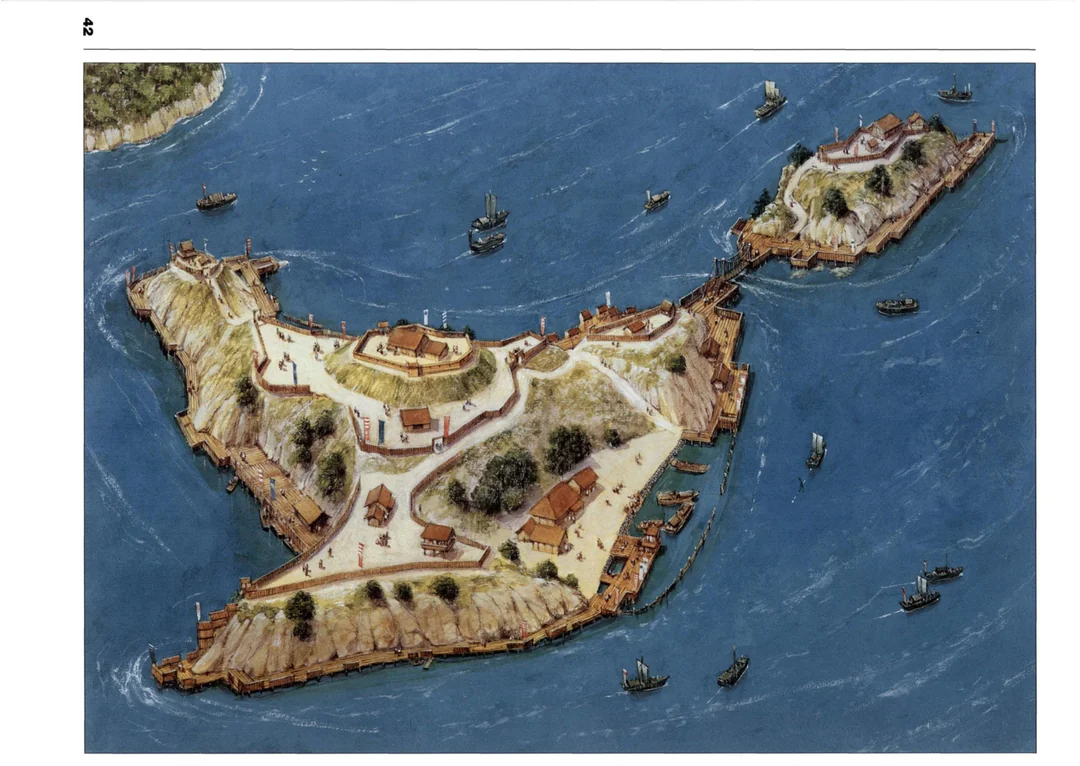

The Seto Inland Sea: The Murakami Theater of Operations

Thanks to this network of fortresses and their knowledge of treacherous currents, the Murakami kaizoku earned their reputation as the undefeated "lords of the seas." No one could pass through the Seto Inland Sea without their knowledge, and those who tried to bypass their outposts risked losing their goods—and their lives. In this way, the Geiyo Islands became not only the center of their power but also a symbol of the Murakami’s military and political genius.

Murakami as "Lords of the Seas"

The Murakami Domain

During the Sengoku period, although they were formally samurai—loyal to powerful daimyō like the Mōri or Ōuchi clans—their methods resembled a more organized group of "maritime entrepreneurs," whose actions were not always legal and could be interpreted as piracy.

The Murakami Domain: Formal Control and Informal Influence

The informal domain of the Murakami was much more extensive, relying on the reputation of their strength and networks of connections among "people of the sea"—fishermen, sailors, traders, and dock workers. For instance, the port of Akamagaseki, while not formally under Murakami control, fell under their unofficial influence due to relationships with local administrators. In every port frequented by ships, it was known that no goods could pass through the waters of Seto without the knowledge or consent of the Murakami.

Murakami as Navigators and Administrators

Managing Coastal Settlements: Examples of Hiburi and Futagami

An even more complex situation existed on Futagami Island, where residents lived under the dominance of various branches of the Murakami clan for years. Before 1582, the island was jointly governed by Noshima and Kurushima, who competed for influence. The residents of Futagami, primarily fishermen and salt producers, were required to pay tributes in the form of seafood, firewood, and other goods. After Noshima seized control of the island in 1582, new laws were introduced that prohibited residents from taking independent actions, such as self-organized ship protection or trade without Murakami approval.

Taxes, Trade, and the Exchange of Goods as Tools of Domination

Taxes, however, were not the only source of income—the Murakami actively participated in maritime trade. They managed a network of ports and trade hubs, collecting fees from passing ships and offering trade escorts. One example of their influence was Shiwaku Island, known as an important trade hub.

Unrivaled Maritime Administrators

Unrivaled Maritime Administrators

Balancing the roles of pirates and guardians of the sea, the Murakami created a unique administrative system that included both efficient management of coastal settlements and control over trade routes. Their knowledge of currents, navigation skills, and superior organization of trade and taxation made them not only the "kings of the sea" but also masters of governance in a challenging maritime environment. Their influence was so extensive that no ship could feel secure in the Seto Inland Sea without their consent.

Organizational Strength

It was this combination of military strength, exceptional organization, and strategic thinking that made the Murakami true "Lords of the Sea." Their domain, both formal and informal, was not just a network of influence but a mechanism of control that allowed them to transform the Seto Inland Sea into their own indivisible maritime kingdom.

Kaizoku Murakami as Poets and Educated Men

The Murakami clan, while known as "lords of the sea" and masters of maritime strategy, also stood out for their extraordinary culture and education, making their group even more remarkable. Contrary to the stereotypical image of pirates as unrefined marauders, the Murakami were well-educated individuals with deep roots in Japanese artistic and literary traditions. Poetry was a particular passion of this clan, and their works reflected their spiritual lives and erudition.

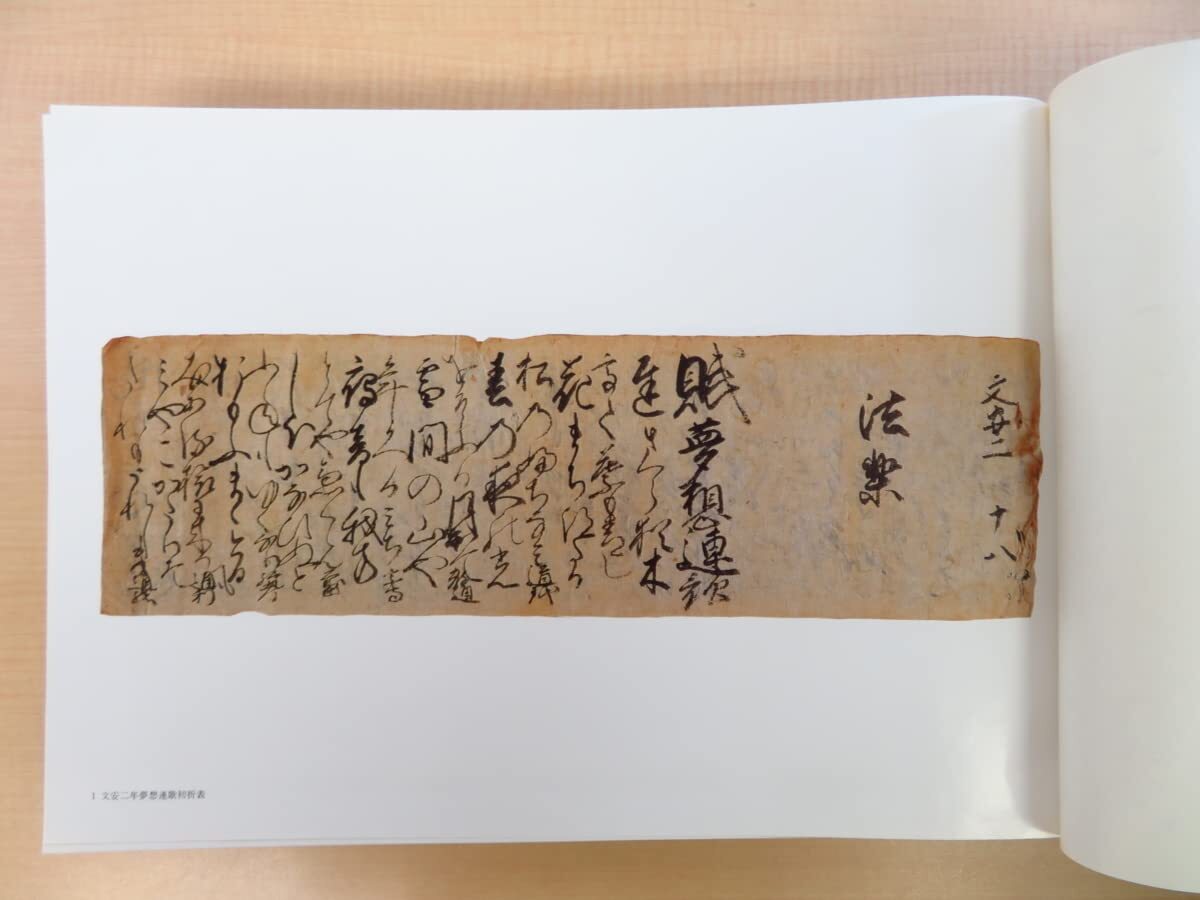

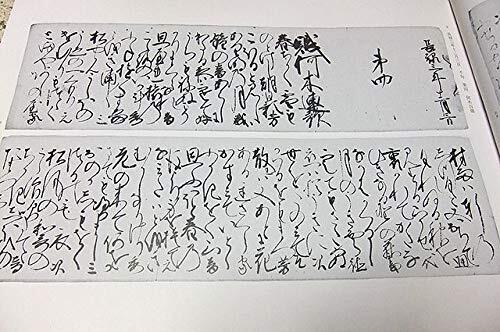

Poetry and the Renga Ceremony

Poetry and the Renga Ceremony

One of the most notable expressions of their love for literature was the composition of renga (連歌)—linked verse poetry created during ceremonies where participants added one verse at a time, building a collective narrative. The Murakami organized renga sessions at the Oyamazumi Shrine (大山祇神社), revered by sailors and warriors as sacred. These poems were often dedicated to protective deities to ensure success in maritime expeditions and battles. Renga became not only a form of prayer but also a way to emphasize their education and prestige. The verses they composed combined homage to the natural beauty of the Seto Inland Sea with their personal experiences as "guardians of the sea."

Education and the Samurai Tradition

Education and the Samurai Tradition

The Murakami were also considered well-educated in the spirit of the samurai ethos. As a samurai clan, they placed great emphasis on education, including knowledge of classical literature, calligraphy, philosophy, and military strategy. Their worldview extended beyond mere survival and enrichment—it blended elements of spirituality, loyalty, and artistic creativity. The clan’s poets and thinkers often drew inspiration from the landscapes of the Geiyo Islands and the turbulent waters of the Inland Sea.

Horaku Renga: Poetry in Honor of Deities

Their education and passion for poetry contributed to their reputation as not only invincible on the seas but also exceptional in intellectual realms. This unique combination of strength, sophistication, and literary prowess made the Murakami legendary figures that transcended the boundaries of the stereotypical pirate image.

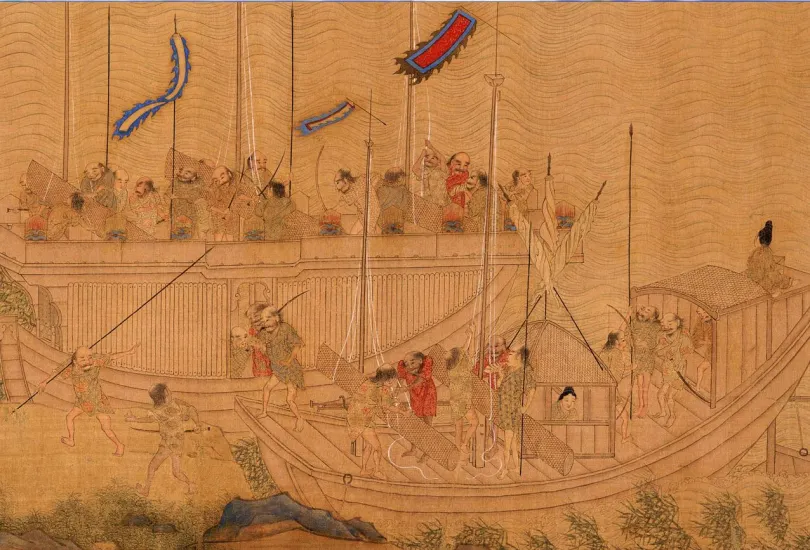

Murakami as a Military Force

The Murakami clan, known as the "lords of the seas," gained fame not only as administrators and sailors but also as masters of maritime strategy, whose actions influenced the outcomes of major conflicts during the Sengoku period. Their military history is a tale of great victories, painful defeats, and complex relationships with powerful patrons such as the Mōri, Ōtomo, and Kōno clans.

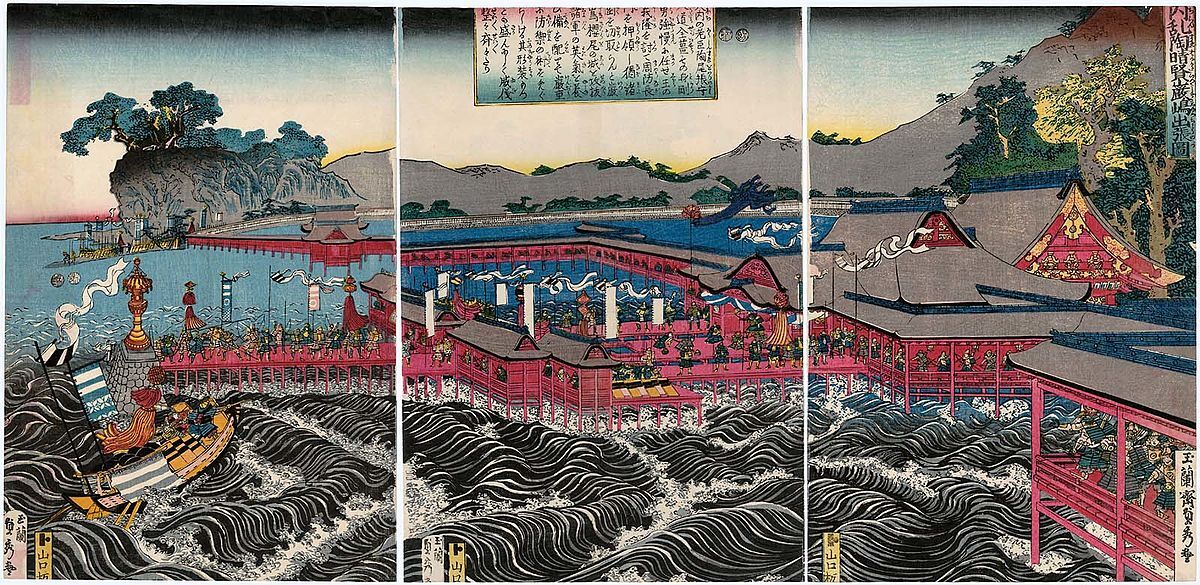

The Battle of Miyajima (1555): Victory Through Maritime Strategy

One of the most memorable moments in Murakami's history was the Battle of Miyajima in 1555, during which the clan played a crucial role in the Mōri clan's victory over the powerful Ōuchi clan. The war was fought for control of the strategically located island of Miyajima, home to the famous Itsukushima Shrine with its iconic red torii gate that appears to float on water.

In this battle, the Murakami utilized their naval expertise and intimate knowledge of the treacherous Geiyo currents to secretly transport Mōri Motonari's forces to the island under the cover of night and storm. Their fleets anchored near the island, enabling the landing of troops who launched a surprise attack on the Ōuchi forces. Thanks to this strategy, the Mōri army captured Miyao Castle, and over 4,700 Ōuchi soldiers were defeated. This success was a turning point in the history of the Mōri clan, which, with the Murakami's support, became one of the dominant powers in the Chūgoku region.

The First Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1576): Triumph Against Oda Nobunaga

The First Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1576): Triumph Against Oda Nobunaga

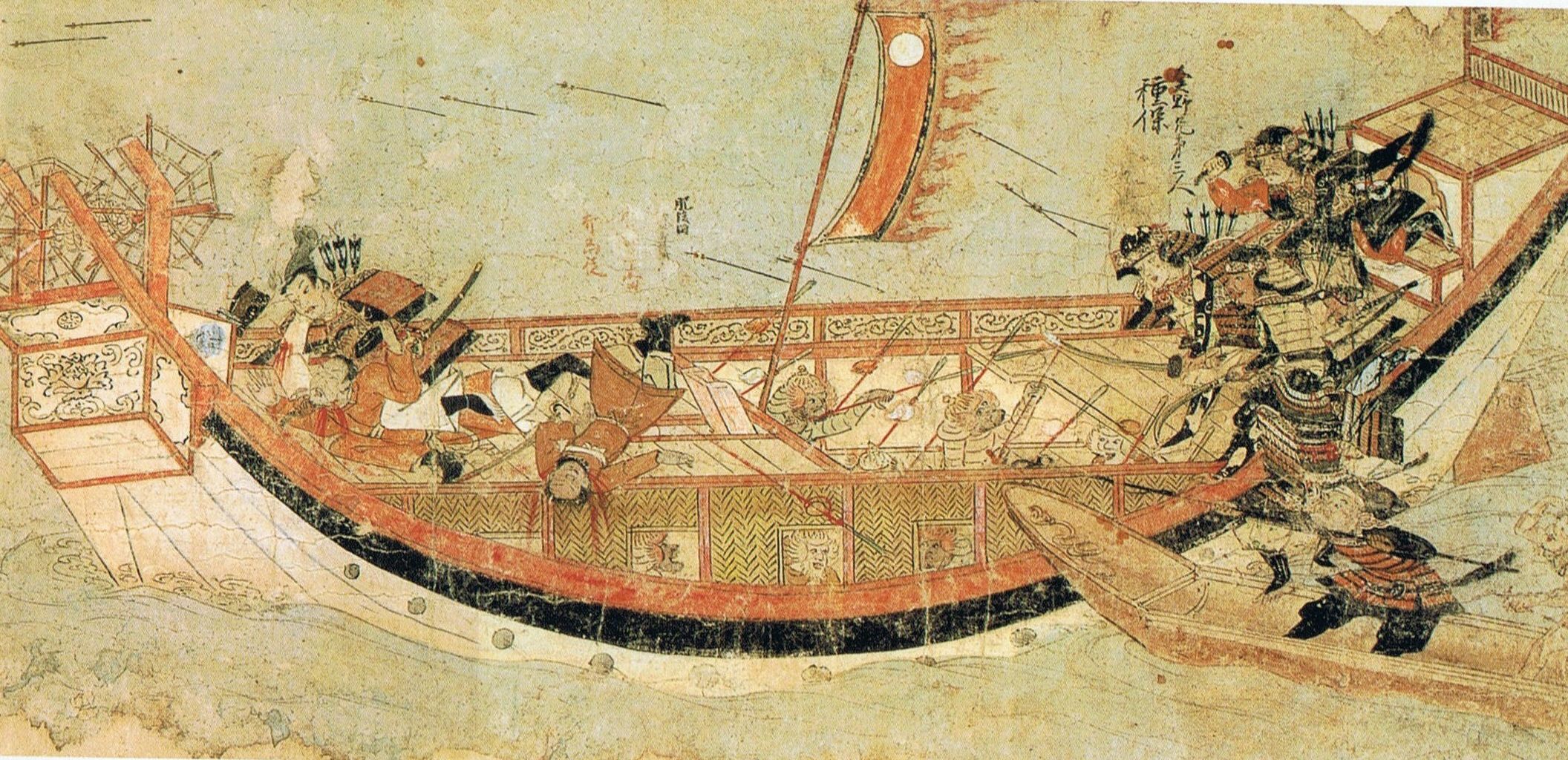

Two decades later, in 1576, the Murakami once again demonstrated their value as maritime strategists during the first Battle of Kizugawaguchi. The Murakami fleet, led by Takeyoshi Murakami's eldest son, Motoyoshi, supported the Mōri clan in their fight against Oda Nobunaga, who sought to cut off supplies to the Hongan-ji fortress in Osaka.

The Murakami employed an innovative tactic involving small, agile vessels capable of effectively attacking Nobunaga's larger ships. Their thorough knowledge of maritime currents allowed them to surprise the enemy, breaking the blockade and delivering supplies to the besieged fortress. This victory was one of the Murakami's greatest triumphs, and their tactics were later described in the famous war treatise "Murakami Naval Battle Principles" (村上舟戦要法, Murakami Shūsen Yōhō).

The Second Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1578): Confrontation With "Iron Ships"

The Second Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1578): Confrontation With "Iron Ships"

Two years later, in 1578, the Murakami faced Nobunaga's fleet again during the second Battle of Kizugawaguchi. This time, however, their opponent was Kuki Yoshitaka, commander of Nobunaga's navy, who introduced a new weapon to the battlefield: ironclad ships (鉄甲船, tekkōsen). These massive vessels, covered in iron plates, were nearly impervious to the arrows and projectiles that constituted the primary weaponry of the Murakami fleet.

Despite their experience and fierce resistance, the Murakami fleet was defeated, and Nobunaga's ironclads played a pivotal role in breaking the Mōri forces. This defeat was a painful blow for the Murakami but also a testament to the changing nature of maritime warfare in Japan, where technology began to outweigh traditional tactics.

Relationships With Patrons: Cooperation and Betrayal

For example, between 1542 and 1582, the Murakami switched sides several times, alternately supporting the Ōtomo, Mōri, and Kōno clans, depending on political and economic benefits. Additionally, different branches of the Murakami clan sometimes fought against each other if their immediate interests dictated so. In 1582, the Noshima Murakami, under the patronage of the Mōri, defeated the Kurushima Murakami and took control of their islands, solidifying their position as the most powerful branch of the clan.

Powerful patrons needed the Murakami to achieve their maritime objectives, while the Murakami used these relationships to expand their influence and secure their domains. This complex game of loyalty and independence made them exceptional players who relied equally on strength and diplomacy.

The End of the Pirate Era: What Remained of the Kaizoku

Toyotomi Hideyoshi's Edict: The End of Pirate Autonomy

This marked the dismantling of the key elements of Murakami power—their control over the Seto Inland Sea and their autonomous "maritime kingdom." However, the Murakami kaizoku did not disappear overnight; some of their structures were integrated into legitimate military and commercial fleets supporting the new centralized government. Others lost influence and gradually faded into obscurity.

Transformation and Decline

Transformation and Decline

Although the Murakami clan ceased their piratical activities, they retained their maritime traditions. Some members of the clan were incorporated into regional military structures as coastal guards or maritime guides. For example, Murakami descendants participated in protecting Japanese diplomatic delegations, such as Korean missions from the Choseon state, which traveled through the Seto Inland Sea. However, some Murakami failed to survive these transitions, disappearing from the pages of history as they struggled against Toyotomi's centralized order.

The Legacy of Murakami in Culture and Traditions

On Innoshima Island, the traditional Horaku dance (奉楽舞, Horaku-mai), once performed by the Murakami to invoke blessings for victory at sea, is still celebrated. This ritual dance combines spirituality and the region’s maritime history.

The ruins of castles, such as those on Noshima and Innoshima, remain visible, serving as reminders of the Murakami’s strategic might. The Oyamazumi Shrine, to which the Murakami dedicated their poems, continues to be a pilgrimage site and a symbol of their cultural contributions.

On the Geiyo Islands, monuments commemorating the Murakami have been erected, such as sculptures of their leaders and fleets. One particularly popular figure is the statue of Tsuruhime, often called the "Joan of Arc of Japan," who fought alongside the Murakami.

Elements of the Murakami story appear in popular culture, such as the series One Piece, where pirates are depicted as charismatic heroes with exceptional abilities (though the series leans more toward southern pirates like the Wakō). There is also a film: Setouchi Kaizoku Monogatari. In games like Total War: Shogun 2, players can fight against or form alliances with the Murakami pirate faction.

Conclusion

The Murakami legacy lives on in local traditions like the Horaku dance and in the memory of the places they once controlled. Their islands, shrines, and castle ruins serve as reminders of an era when this clan ruled the waters of Seto Naikai, and their name commanded respect among sailors and warriors.

The Murakami were not only lords of the seas but also individuals who understood that true power lies not just in military strength but in the ability to create order from chaos—through effective administration.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Wakou – Pirate Freedom, Independence, and Terror on the Seas of Japan, Korea, and China

Maurycy Beniowski: The Adventures of a Daring Pole in Edo Period Japan

The Republic of Ezo – A One-of-a-Kind Samurai Democracy

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Unrivaled Maritime Administrators

Unrivaled Maritime Administrators Poetry and the Renga Ceremony

Poetry and the Renga Ceremony Education and the Samurai Tradition

Education and the Samurai Tradition

The First Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1576): Triumph Against Oda Nobunaga

The First Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1576): Triumph Against Oda Nobunaga The Second Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1578): Confrontation With "Iron Ships"

The Second Battle of Kizugawaguchi (1578): Confrontation With "Iron Ships" Transformation and Decline

Transformation and Decline