Goddess Uzume dances naked and, with her sacred antics, saves us from sorrowful seriousness – Japanese mythology, how timely today

「もっと踊ってよ、アメノウズメさん

腕ふり回し、汗かき散らし、

首しならせて、

踊って、踊って、もっと、もっと」

"Dance for us again, Ame no Uzume

Swing your arms, shake off the sweat

Tilt your head toward the heavens

And dance, dance, again, again"

— Takako Arai (新井高子), Asa o kudasai,

Chizu o moyasu (『地図を燃やす』), 2013

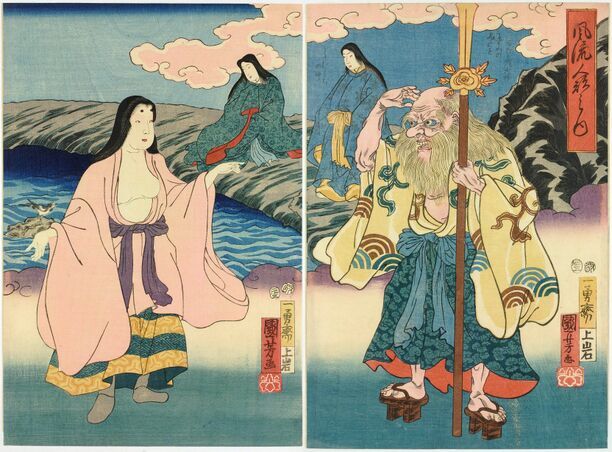

In Japanese mythology, femininity does not appear as a single fixed ideal, but as a dramatically stretched triad of archetypes: the mother, the warrior, and the shamaness. In this view, Izanami—the primordial mother of the world—is the Great Mother, both creative and destructive. Amaterasu is the virgin warrior—closed within her radiant dignity, separated from the body and emotions. And Uzume? Uzume is the third pole—wild, sensual, laughing, manifesting in rhythm, body, and intimacy. For contemporary scholar Hirosawa Aiko, Uzume is more than a myth—she is a model of 21st-century female identity. Not one that conforms to norms, but one that transforms them. Uzume does not seek acceptance—she creates a new space in which spirituality does not exclude sensuality, and tenderness can coexist with strength. Hirosawa calls this assertive receptivity (shutaiteki juyōsei): femininity not as an assigned role, but as a conscious choice. So let us see what we can still learn today from the ancient mythology of Japan!

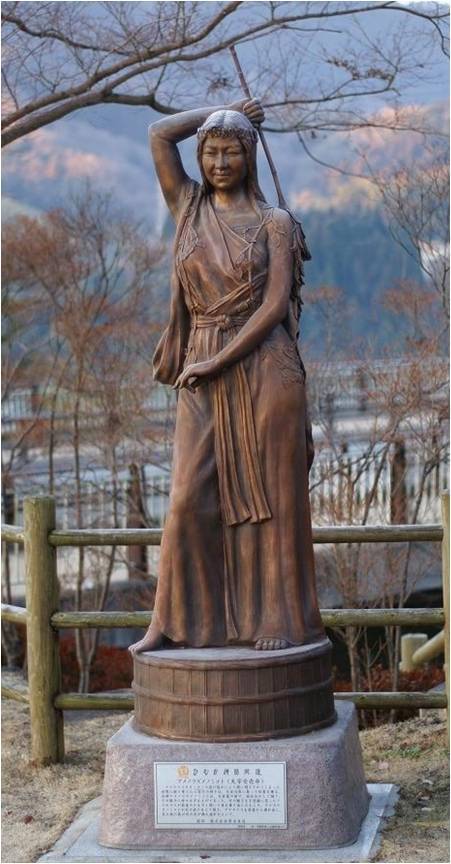

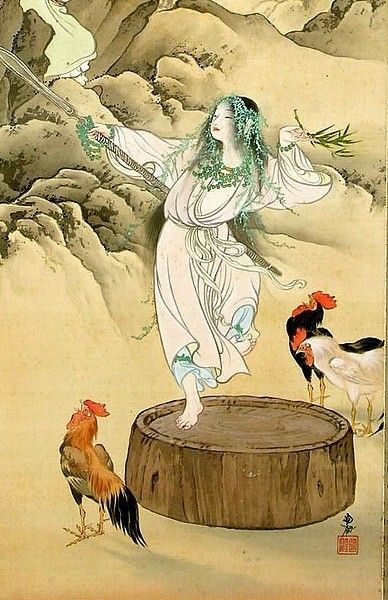

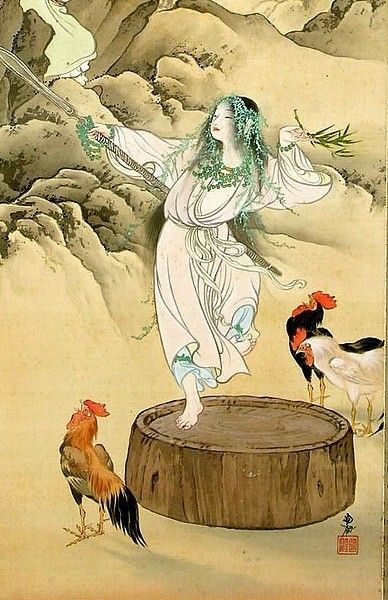

Ame no Uzume – goddess of dawn, dance, and joy

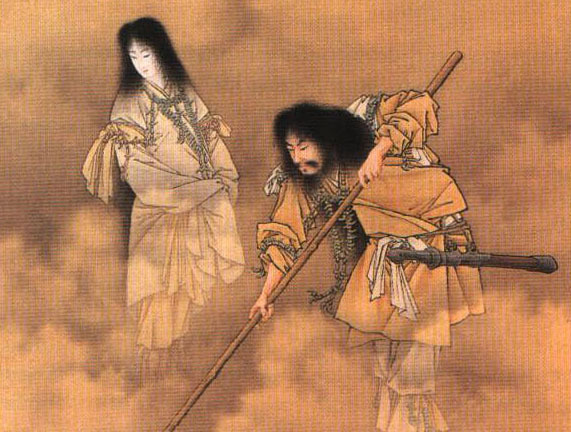

In this myth, the Sun—goddess Amaterasu—after a series of humiliations and acts of violence from her brother, the storm god Susanoo, hides herself away in the cave Ama-no-Iwato, taking with her all the light of the world. Heaven and earth fall into darkness. The world begins to die: plants wither, people suffer from hunger, and the divine order is suspended. Then eight hundred spirits gathered at the entrance to the cave convene a council. Attempts at persuasion, spells, and pleading fail—Amaterasu does not respond.

And then Uzume appears.

This dance was not merely a spontaneous ecstasy. In the Shintō tradition, it is regarded as the birth of kagura—ritual dance in honor of the kami. The kagura performances, still staged in Shintō shrines today (though no longer nude), re-enact this scene through the miko priestesses, who pass down the memory of Uzume from generation to generation. Uzume thus became the patroness of dawn (for she awakened the Sun), of laughter (for laughter heals), of theatre (for she began performance), and of fertility (for the dancing body creates life).

Her presence can still be felt today in Noh theatre, in the comedic kyōgen performances, in ceremonial kagura, but also in boisterous festivals and in laughter that unexpectedly breaks the silence—as if Uzume herself were reminding us that joy is not a luxury, but the force of life itself.

What does her name mean, and what secrets does it hold?

In the most frequently encountered classical sources, the goddess’s name appears in two versions:

► 天宇受売命 (Ame no Uzume no Mikoto) – from the Kojiki

► 天鈿女命 (Ame no Uzume no Mikoto) – from the Nihon shoki

Although the phonetic readings are the same, the differences in kanji carry various nuances of meaning, the interpretation of which requires both linguistic and cultural knowledge.

天 (Ame) – “heaven”

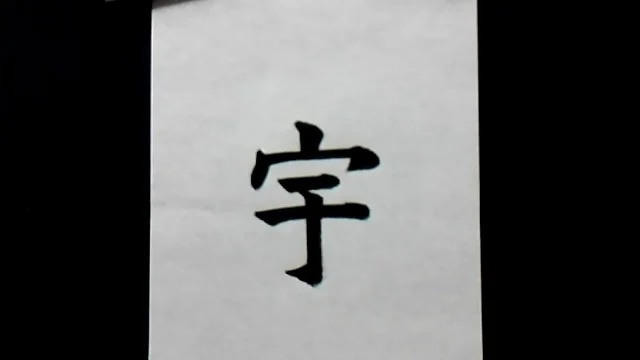

宇 / 鈿 (U) – “space, firmament / ornament”

宇 / 鈿 (U) – “space, firmament / ornament”

Here we encounter the first significant difference between the two versions of the name.

► In the spelling 天宇受売命, the character 宇 is used, meaning the celestial firmament, roof, or the expanse of the universe. It relates to the idea of a cosmic canopy, and thus also the boundary between heaven and earth. This character also appears in the word uchū (宇宙) – “cosmos.”

► In the alternative version from Nihon shoki: 天鈿女命, the character 鈿 (u) is much rarer and more poetic. It means a metallic ornament, inlaid jewelry, and in a ritual context—a feminine decoration used during kagura dance. It alludes to Uzume’s status as a goddess of performance, adorned with gleaming accessories that shimmer in the light of ritual fire.

受 (Zu) – “to receive, receptivity”

受 (Zu) – “to receive, receptivity”

The character 受 (read here as zu) signifies receiving, accepting, receptivity, and can also be interpreted symbolically as readiness for intimacy—be it spiritual, sexual, or ritualistic. In the feminine and sacred context, it indicates the ability to incorporate heavenly power, but also to open oneself to ecstasy, laughter, and life. This is the core of Uzume’s entire symbolism—the goddess who receives, but also transforms.

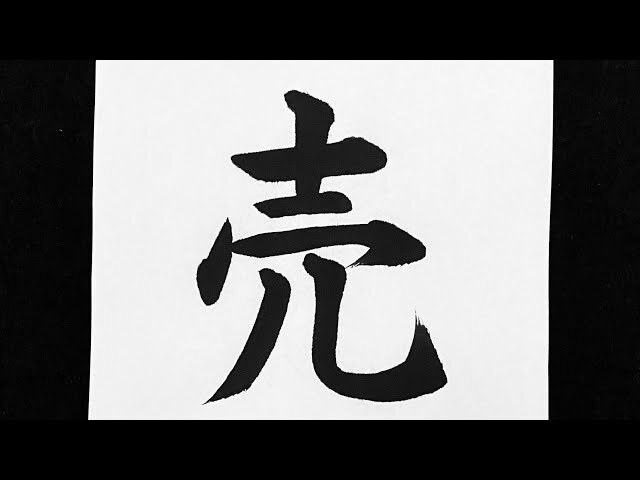

売 / 女 (Me) – “woman”

► 売 – although it now means “to sell,” in ancient Japanese it could be used phonetically as me (woman), in an archaic function. This type of usage—employing a character for its phonetic rather than semantic value—is a classical technique in man’yōgana, the ancient Japanese writing system.

► 女 – a far more straightforward character for “woman,” read as me or onna. In the Nihon shoki version, where it appears as 鈿女命, it emphasizes that Uzume not only receives divine energy, but embodies femininity itself.

Possible interpretations of the name Ame no Uzume:

Possible interpretations of the name Ame no Uzume:

► “The woman who receives heavenly energy”

→ Ame (heaven) + u (firmament, space) + zu (to receive) + me (woman)

→ An archetype of woman as a channel between heaven and earth—a medium of divine ecstasy, a guide of dawn and life.

► “Ornamented woman of the heavens”

→ With the 鈿 (metallic ornament) variant—portrays Uzume as an artist and ritual dancer, whose body and movement are both an adornment of the world and a tool of sacred transformation.

► “She who dances between heaven and earth”

→ A metaphorical interpretation, capturing her role as a liminal figure—a woman present at the border between worlds: sacred and profane, life and death, body and spirit.

Note on archaic language forms

It is worth remembering that the language of the Kojiki and Nihon shoki—written in the 8th century—employs archaic Japanese and frequently uses the man’yōgana system, where Chinese characters function primarily as carriers of sound rather than meaning. This means that many kanji used in the names of deities operate on a symbolic-phonetic level, making their interpretation multi-layered.

Example: the writing 鈿女 may be phonetic (read as Uzume), but semantically it evokes associations with ornamentation and femininity—something that perfectly aligns with Uzume’s role as a divine dancer, whose body and gestures are at once art, sanctity, and an act of world transformation. Thanks to such a polysemous name, Ame no Uzume is not only a mythological figure but also a linguistic poem about femininity, laughter, and ritual.

Let us recall the myth

Legend about Amaterasu in a Cave and Dancing Ame no Uzume

As part of a strange divine wager, Amaterasu and Susanoo began creating children from sacred objects they gifted each other—to prove the purity of their intentions. But Susanoo, as was his way, crossed the line. He destroyed rice fields, knocked down the heavenly gate, and finally, in a fit of rage, threw a dead horse—sacred to Amaterasu—straight into her weaving hall, causing the death of one of her handmaidens. Outraged and plunged into grief, Amaterasu withdrew into a cave called Ama-no-Iwato—a rocky cavern in the heavens—sealing it behind her with a massive boulder and cutting the world off from her light.

And then, seeing her own reflection in the gleaming mirror hung at the entrance—Amaterasu believed it to be a new sun goddess—she stepped forward. At that moment, a strong god standing to the side moved the boulder away, and light once again flooded heaven and earth. Uzume’s dance not only restored the day but also gave rise to the ritual theatre of kagura—and initiated the tale of feminine power that restores harmony to the world not with anger, but with laughter and the courage to be oneself.

Strong Feminity of Uzume

Dance as a spiritual and revolutionary act

Her movements created an archetype: the priestess dancing in trance, a medium between worlds. To this day, miko—Shintō priestesses—perform ceremonial kagura dances as an expression of communion with the kami. Rhythmic gestures, fans, drums, bells—all of it refers back to Uzume’s primal act, which led the world out of shadow.

That is why Uzume is considered not only the inventor of dance, but the inaugurator of ritual laughter as a form of spiritual transformation. Laughter became the gate between the world of suffering and the world of light—a kind of cathartic exorcism that requires no words, only rhythm, body, and courage.

Ecstasy instead of silence – Uzume in contrast to Amaterasu

Ecstasy instead of silence – Uzume in contrast to Amaterasu

In the myth, Uzume and Amaterasu meet as two poles of feminine being: the withdrawn, lonely, silent sun goddess, and the dancing, noisy, sensual goddess of dawn. Amaterasu flees into darkness, mourning, and the death of the world. Uzume—acts. Not through force, not through logical persuasion, but through active ecstasy that disarms the darkness. Uzume exposes her body, disarms convention, crosses boundaries—and that is precisely why she is effective.

This opposition is not a negation, but a complement (just as dawn is not the opposite of the sun—thus: Uzume is the complement of Amaterasu). Without silence—Uzume’s ecstasy would be mere buffoonery. Without laughter—Amaterasu’s darkness would never have lifted. Japanese mythology here reveals something deeper than a comical story of the gods: it shows the balance of feminine forces, which together create wholeness—and the courage of laughter that heals the world.

Uzume and the paradigm shift – from taoyame to ozu-me

Yet Ame no Uzume, although referred to as taoyame in one passage of the Kojiki, eludes this label entirely. When all the gods stood helpless before Amaterasu’s sealed cave, it was she—not the strongest, not the most hierarchically important—who stepped forward. She initiated action. She approached the problem from a seemingly “improper” angle—through laughter, obscenity, dance, and corporeality. And yet, it was her gesture that brought back the light. In this way, Uzume embodies a reversal of the paradigm—she is a taoyame who acts like an ozu-me (a powerful woman).

This radical contrast makes Uzume an archetype of the transformative woman—who can unite gentleness with strength, warmth with initiative, closeness with leadership. In this sense, she is not the opposite of taoyame, but its spiritual and social evolution.

Femininity as choice, not imposition

In this sense, Uzume becomes the embodiment of femininity as an act, not as an identity imposed by society or myth. Her dance and laughter are not an escape from norms, but a rewriting of them—on her own terms.

The sacred shamelessness – psychological and social dimensions of Uzume

In Japanese culture, where shame (haji) often functions as a moral and social regulator, Uzume becomes a therapeutic exception. She laughs at what cannot be spoken. She dances where silence once reigned. She is needed precisely because she transgresses—not to destroy, but to renew.

The Woman of Japanese Mythology

Uzume not only leads Amaterasu out of the cave—she also shows the path to inner integration. Symbolically, she heals the fragmented female identity, uniting the spiritual and the corporeal, the serious and the playful, the sacred and the sensual. This is not about a return to archaic wildness, but about an acceptance of wholeness—a place where joy, spontaneity, and strength do not exclude one another.

The contemporary scholar Hirosawa Aiko takes this psychosocial analysis a step further. In Uzume, she sees a model of 21st-century feminine identity—not one that “adapts” to a role, but one that chooses. Hirosawa calls this attitude shutaiteki juyōsei—“assertive receptiveness”: the awareness that one can be tender and strong at the same time, that one can laugh out loud and manage life with dignity. Uzume does not fight for a place in the system—she creates a new space, where corporeality, spirituality, and community dance together. In a world full of pressure and division, her figure becomes increasingly relevant: as a symbol of a femininity that need not be “ideal,” but true enough to bring light back into the cave.

Ame no Uzume Today – Between Symbol and Practice

Do we need more Uzume today? A woman who does not apologize for existing. Who does not ask whether it is appropriate to laugh. Who does not hide her body, but turns it into a tool of transformation. Perhaps that is why she keeps reappearing— in manga, in performances, in theatre, in the rituals of new spiritual movements, in women’s circles, and on activist forums. Not as a decorative goddess, but as an archetype—free, wild, present.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Born in hell, buried in Jōkanji – what have we done to the thousands of Yoshiwara women?

Kingdom of Ryūkyū: Where Karate Was Born, Religion Belonged to Women, and Longevity Was the Norm

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

宇 / 鈿 (U) – “space, firmament / ornament”

宇 / 鈿 (U) – “space, firmament / ornament” 受 (Zu) – “to receive, receptivity”

受 (Zu) – “to receive, receptivity” Possible interpretations of the name Ame no Uzume:

Possible interpretations of the name Ame no Uzume:

Ecstasy instead of silence – Uzume in contrast to Amaterasu

Ecstasy instead of silence – Uzume in contrast to Amaterasu