In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun – The Story of Amaterasu

A goddess “rewritten” countless times

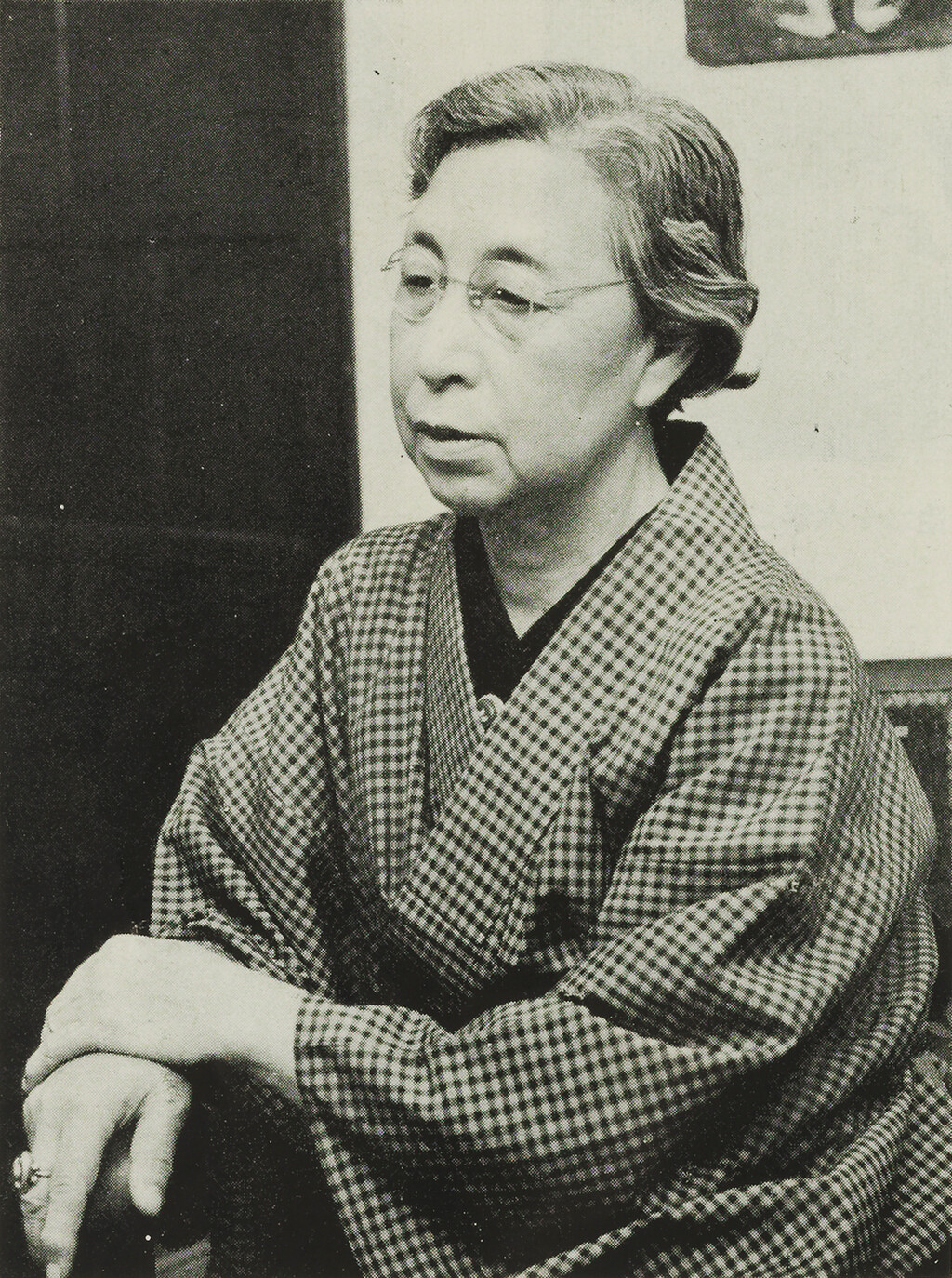

In the first issue of the journal Seitō, Raichō wrote:

"In the beginning, woman was the Sun.

Today, she is the Moon,

living by borrowed light."

Raichō reinterpreted the myth of Amaterasu’s cave: the goddess hiding away from the world became a metaphor for the exclusion of women, and the mirror that lured her out symbolized rediscovering one’s own identity. Her call was unambiguous — a woman should not be the moon that reflects someone else’s brilliance but the sun that shines from within. In this sense, Amaterasu becomes a symbol not only of divinity but of subjectivity. The myth, which for centuries cemented political order, became the foundation of emancipation and feminism. And perhaps that is why it remains so alive today: it keeps returning to a question that concerns us all — do I shine with my own light, or merely reflect another’s? So let us now trace the story of this extraordinary goddess.

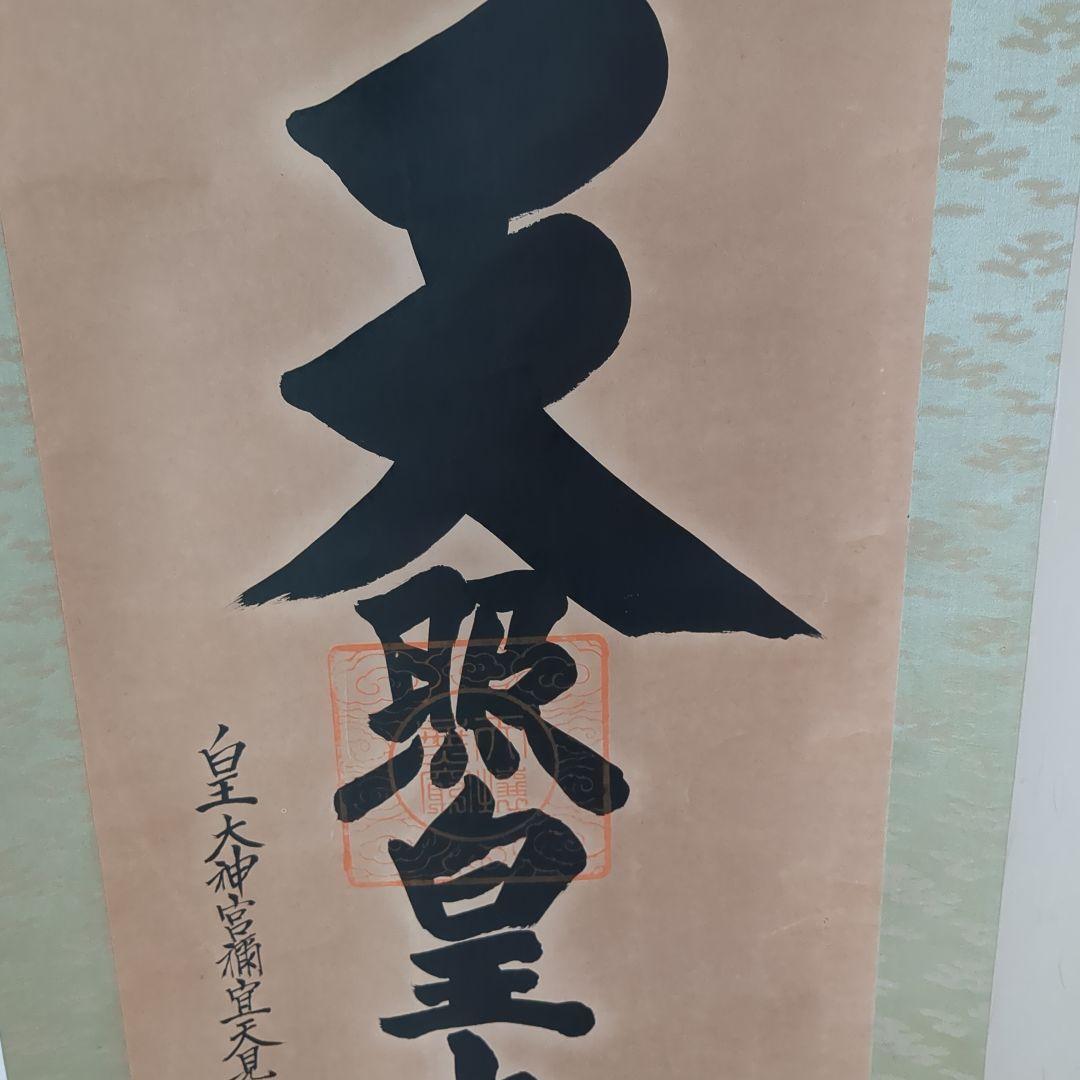

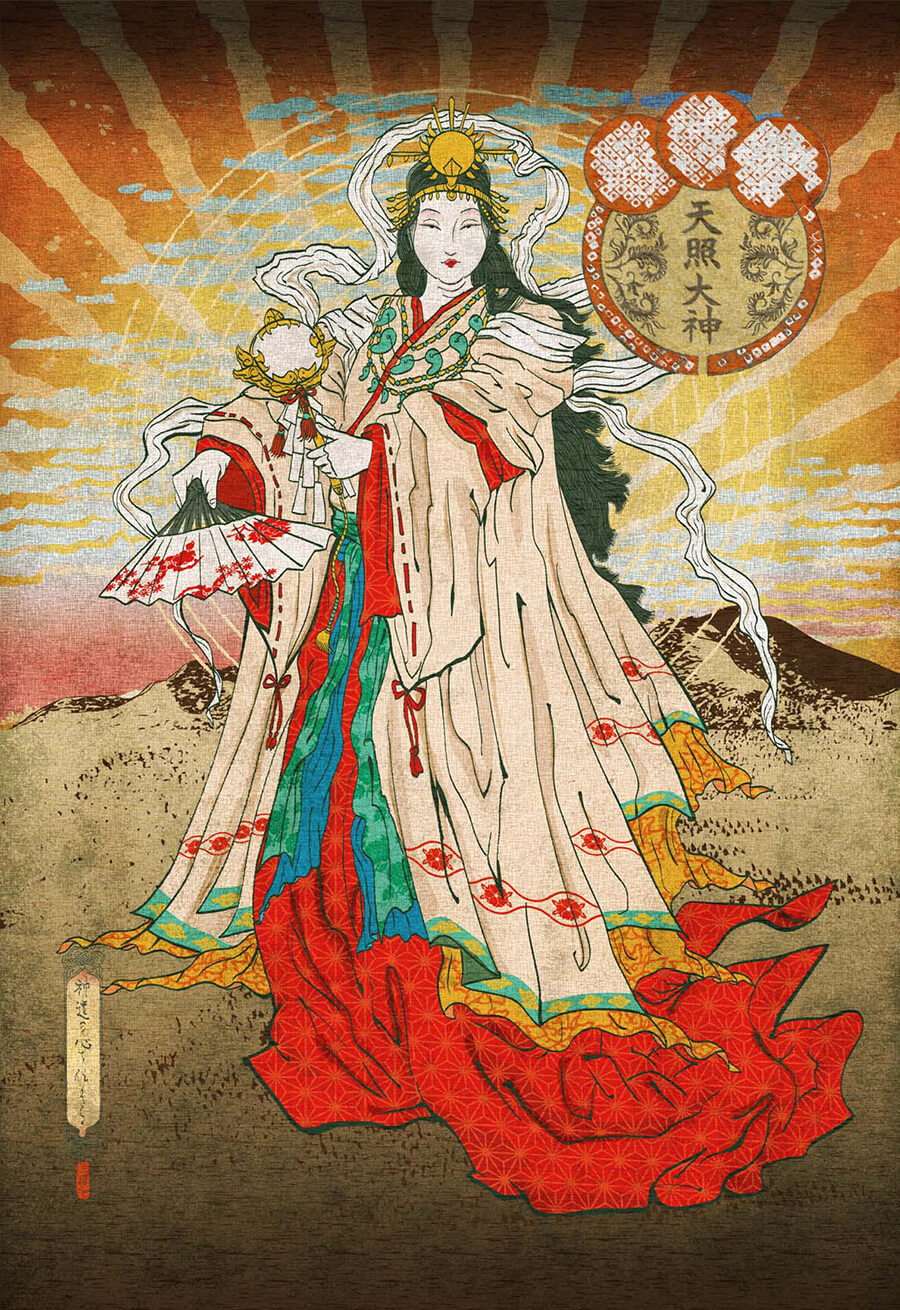

The name of the goddess

The first character, 天 (ama or ten), means “heaven” — both in the physical and metaphysical sense. In classical Japanese, ama referred to heaven as the domain of the gods, but also to the celestial order upon which the harmony of the world depends. The second character, 照 (terasu), comes from the verb terasu — “to illuminate, to brighten, to dispel darkness.” Together, they evoke the image of a being whose light sustains the rhythm of life, defines the order of day and night, and serves as the source of vitality. The final element, 大神 (ōmikami), is an honorific title: ō — “great,” kami — “deity.” Thus, the full name points to someone standing above other gods, endowed with a unique status within shintō.

In mythological sources such as the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, we also find other designations for the goddess. One of the oldest is Ōhirume-muchi no kami (大日孁貴神), which can be translated as “The Great Noble Being of the Sun.” This archaic name suggests that she may have been venerated not so much as an individual goddess, but as the embodiment of the sun itself — its life-giving force, rhythm, and radiance. In even earlier accounts, we also encounter the form Amateru, stripped of any marker of gender. This is a crucial clue: at the dawn of her worship, Amaterasu may have been perceived as a gender-neutral deity, and only later, influenced by the rise of priestesses and female rulers in Ise, did her image acquire an explicitly feminine aspect (we will return to this point later).

The origins of Amaterasu’s cult

Before Amaterasu

Among the preserved legends, one stands out: the tale of seven suns, which one day appeared simultaneously in the sky, scorching the earth with their fierce radiance. Unable to endure the heat, the people turned to Amanojaku — a mythical giant and trickster, who shot down the excess suns with his bow until only one remained in the sky. Interestingly, similar motifs appear in the mythologies of Southeast Asian peoples, as well as in Chinese tales of the hero Hou Yi. Japanese solar myths did not emerge in isolation — they were part of a broader, transcultural sphere of imagination in which the sun served as the axis of cosmic order.

Another type of narrative revolved around conception by a sunbeam. One tale preserved in the Kojiki tells of a girl who became pregnant by sunlight and gave birth to a red stone. This stone later transformed into a woman — Akaruhime — who became the wife of Prince Ame-no-Hiboko from Shilla (modern Korea). This motif is significant, for it symbolically links sunlight with life itself and points to the cultural ties between early Japan and the Korean Peninsula. In the kingdoms of Shilla, Koguryŏ, and Paekche, it was believed that rulers were descended directly from a solar deity — and as Matsumae Takeshi emphasizes, this model of legitimizing authority also permeated Japan.

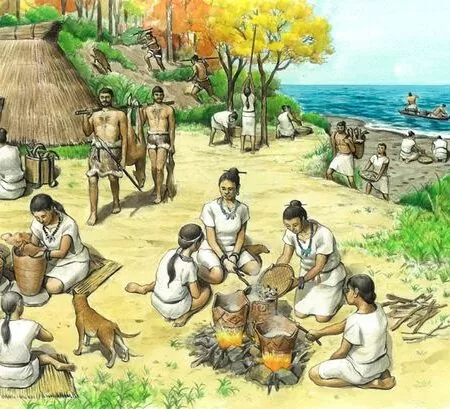

This multitude of myths and local sun stories suggests that the cult of Amaterasu did not arise suddenly, nor from a single source. It was instead the result of a slow synthesis of many traditions, rooted in agricultural, fishing, and maritime communities. Early Japan did not know a singular “goddess of the sun” — it knew many tales of light. Amaterasu only later became the one who “shines the brightest.”

Amaterasu as the Deity of the Ama People

According to the Japanese historian and scholar of religion Matsumae Takeshi (松前 健, 1929–2002), it was the Ama who were the first to worship Amateru — the primordial, gender-neutral form of the solar deity that, over time, transformed into the Amaterasu we know today. For the Ama, sunlight had a practical, navigational meaning: it dictated the rhythm of fishing, the directions of sea routes, and the time to return to harbor. Their rituals were thus intimately tied to the sea and the sky.

The geographical symbolism here is profoundly eloquent. Ise lies on the eastern coast of Japan, facing directly toward the rising sun. For the Ama, this was the place where the day began earliest, where the first rays of dawn touched the earth. This “gateway of the rising sun” gave the rituals of Ise a unique significance. It was here that the transformation began — from a local fishermen’s deity to the central goddess of state shintō.

Thus, long before Amaterasu became associated with the emperor and was elevated to the throne of the gods, her cult grew out of a living relationship between humans, the sea, the sunrise, and light itself. She was the guide of fishermen, the guardian of the morning horizon, the goddess who illuminated the sea routes. Only later did she become the symbol of the state.

The “Elevation” of Amaterasu

It was only in the 5th–6th centuries that the Yamato clan began a process of mythological centralization. This was an era of rapid state formation, and a strong, unifying symbol of authority was needed. In this context, the deity venerated locally at Ise was chosen and reimagined as the divine ancestress of the imperial line. In practice, this was a process of politicizing religion: the goddess became a cornerstone of the new Yamato ideology, and the myth of her divine origin served to legitimize imperial power.

As a result, Amaterasu became not only the goddess of the sun but also the divine source of authority, a symbol of national unity, and the keystone between mythology and politics.

Amaterasu Enters Politics

7th–9th Century

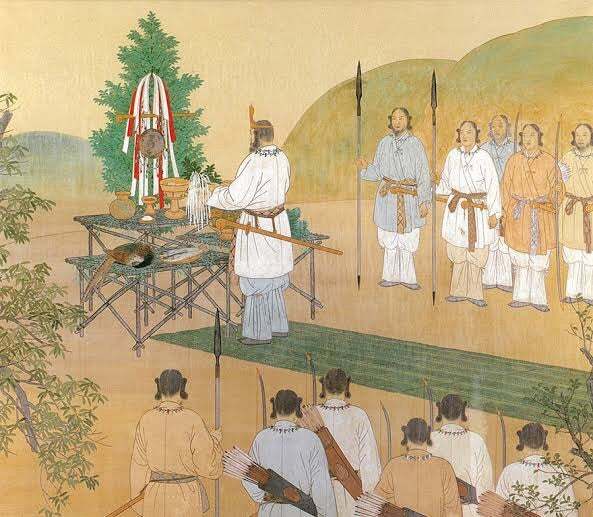

It was during this period that the institution of the saio — ritual princesses — was developed. According to tradition, each new empress of the Yamato dynasty would select an unmarried imperial princess, who, after undergoing a lengthy period of ritual purification, would travel to Ise Jingū to serve as the high priestess and medium of Amaterasu. These saio were not merely “voices of the goddess” but her symbolic incarnations. Over time, this powerful image of the female priestess at the heart of the cult contributed to reshaping Amaterasu’s identity into that of a goddess — the mother of Japan — a vision that became fixed in the iconography and rituals of the Nara period.

Amaterasu and Buddhism

It was a brilliant solution. Instead of conflict between shintō and Buddhism, the two systems were merged. Buddhist temples began to appear in Ise, and texts such as Ise Shintō (13th century) portrayed Amaterasu as an expression of universal Buddhist truth. This integration opened the cult to new social layers: pilgrims to Ise were no longer limited to aristocrats, but also included peasants, monks, and artisans.

It was in the medieval period that the phenomenon known as okage mairi — mass pilgrimages to Ise — first emerged, later flourishing during the Edo period (17th–19th centuries), when such pilgrimages could gather hundreds of thousands of people. Pilgrims traveled barefoot, carrying talismans and miniature mirrors — symbols of Amaterasu — believing that the goddess herself was calling them.

Numerous folk legends also arose during this time. In one tale, Amaterasu appears to a poor girl, instructing her to find a sacred stone in the Isuzu River; in another, peasants speak of a “dancing sun” during the Niiname festival, when the goddess was said to bless the harvest. These stories reveal how Amaterasu ceased to be merely the deity of the court and became a communal goddess, close to the people — a transformation that significantly expanded her cultural reach.

Amaterasu Supports Modern Meiji

Amaterasu Supports Modern Meiji

With the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Amaterasu was “rewritten” once again — this time by a modernizing state in search of a myth of exceptionalism. The government rejected Buddhist syncretism and reinstated shintō in its “pure” form as the state religion (kokka shintō).

The emperor was declared a living god, a direct descendant of Amaterasu, and Ise Jingū was transformed into the spiritual heart of a new national identity. Texts such as the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki became compulsory reading in schools. State festivals, coronation rituals, and imperial regalia — the mirror Yata no Kagami, the sword Kusanagi, and the jewel Yasakani no Magatama — constantly reminded the nation of Japan’s divine origins and its “mission to lead the world.”

Psychologically, this was an immensely powerful move. Amaterasu became the light that organized collective identity, the symbol of order, purity, and uniqueness. When, in 1890, the “Imperial Rescript on Education” was issued, children across the country were taught that “Japan is the land of the gods” (shinkoku), and the emperor — the embodiment of divine will. Even the architecture of Ise Jingū was “refreshed” to emphasize the supposed ancient continuity of the cult, though many of its “ancient” rituals were, in fact, reconstructed during the Meiji period.

A Brief Reflection on the Goddess’s History

Her light is not merely physical radiance — it is consciousness and identity. In Japan, where the concept of the individual long yielded to the primacy of the community, Amaterasu became a projection of what “we” means: imperial authority, unity of the people, cultural uniqueness. Her cult demonstrates that myth can be, all at once, a political instrument, a spiritual space, and a social matrix of memory.

“In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun”

The Birth of the “New Women”

Raichō (1886–1971), raised at the crossroads of tradition and modern thought, no longer wanted women to be mere echoes of others’ voices within culture. From the start, she was guided by what we might today call cultural feminism: rather than imitating masculine ideals, she sought to elevate the value of distinctly “female” experiences — motherhood, caregiving, bodily autonomy — and sever them from their culturally assigned inferiority. Her strategy was not a simple import of Western debates. Instead, she reworked her own tradition and invoked the myth every Japanese person knew best — the story of Amaterasu.

This was both subversive and deliberate. The Meiji authorities had transformed Amaterasu into an instrument of state legitimacy; Raichō reached for the same symbol but shifted its meaning: from a national myth, she forged a myth of emancipation.

The Manifesto

The Manifesto

Her manifesto opening the first issue of Seitō strikes with its simplicity and power: “In the beginning, woman was the Sun. Today, she is the Moon.”This is no ornamental phrase. It is a poetic compression of the cosmic order — and of Japan itself.

Woman as the Sun: the source of life, autonomy (“she shines of herself”), agency, directness. This is precisely Amaterasu — she does not reflect another’s brilliance; she is that brilliance. In a culture where — unlike so many others — the sun is a goddess, this metaphor carries an immediate resonance.

Woman as the Moon: existing “through others,” reflecting another’s light. This symbolizes the social arrangement in which a woman is cast as a mirror — an aesthetic accessory rather than a subject in her own right.

Raichō’s formula is both diagnosis and program: it points to a lost position and issues a call for return. Within a short text, she condensed a theory of symbolic power: whoever decides who shines and who merely reflects light decides the distribution of roles within society. Notice a subtle rhetorical detail: Raichō uses the singular — “woman.” This is not a statistic; it is an archetype. That is why it works so powerfully: it speaks both to “every woman” and to “this one” — to you.

The Cave as a Metaphor of Exclusion

The Cave as a Metaphor of Exclusion

In the myth of Amano-Iwato, Amaterasu, wounded by Susanoo’s violence and chaos, retreats into a cave. The world plunges into darkness; the gods panic. In a feminist reading, this becomes a striking image of withdrawal: when the woman — the “sun” — is pushed aside, humiliated, threatened, she hides in a place beyond reach, and the world loses its light.

The gods lure her out through a ritual of joy and laughter: the dance of Ame-no-Uzume, festivity, noise, the mirror. From the perspective of emancipation, the communal aspect is crucial: the return of light is made possible by collective action. This anticipates later women’s movements — solidarity as the condition of change. And then there is the Yata no Kagami, the sacred mirror: Amaterasu emerges when she sees the radiance of “another Amaterasu.” Symbolically, the woman recognizes her own face instead of seeking validation in someone else’s gaze. It is the antithesis of “moonlike” dependence.

The relationship between Amaterasu and Tsukuyomi — sun and moon — completes the metaphorical picture. After Tsukuyomi kills the goddess of food, the sun and moon are forever separated; day and night will never meet again. For Raichō, this becomes an apt metaphor: replacing the sun with the moon in public roles means that women are allowed to “shine” only when someone else’s light permits it. That is precisely the condition her manifesto names and challenges.

Why does this myth work so powerfully in an emancipatory context? Because it is not an elitist citation but a core of cultural memory. Raichō’s strategy was to reverse the current: to turn a myth that served the state into a myth serving individual subjectivity.

What Came After Raichō

The following decades brought new waves, new emphases: from the protection of motherhood (in line with Raichō’s cultural feminism), through postwar struggles for full citizenship, to the radical slogans of the 1960s and 70s (including heated debates on contraception and abortion rights). In sociological terms, as Muta Kazue notes, it is precisely here that we see the latent power of feminist history — its ability to generate new “lights” within the public sphere.

And what remains of Amaterasu? Not just rebellion, but potential: the idea that womanhood is not about reflecting someone else’s brilliance but about generating one’s own; that “emerging from the cave” is often a process rather than a single act; that the mirror — even the one at Ise — is less a fetish than an invitation for women to recognize their own worth.

Raichō achieved something brilliantly simple: she retuned the symbolism without breaking the melody. Amaterasu had been the state’s sun; she became the feminine light of consciousness. And that is precisely why this metaphor still resonates — in literature, in social movements, in everyday choices. Because the question she posed remains timeless: do I shine with my own light, or do I merely reflect another’s?

Amaterasu in Contemporary Japan

What is remarkable is that even in today’s secular world, Ise Jingū continues to draw record numbers of worshippers. In 2013, over 14 million pilgrims visited the shrine. Some come out of genuine faith; others seek to touch a living tradition they view more as cultural heritage than religious duty. Indeed, the rituals at Ise today possess a dual character: they are both religious ceremonies and state events.

In elementary schools, children still learn about Amaterasu as part of lessons on national mythology. Textbooks emphasize her role as the divine ancestress of the imperial line and guardian of cosmic order. Sociological studies reveal — as one might expect in such a modern society — that younger generations (and in Japan, “younger” often means under sixty) tend to view this knowledge more as cultural inheritance than as an act of faith.

Contemporary Japanese women, especially those engaged with feminism, increasingly reinterpret Amaterasu as a symbol of autonomy and creative power, drawing directly on the legacy of Hiratsuka Raichō.

Amaterasu in Pop Culture

In the 21st century, Amaterasu has transcended the boundaries of religion and tradition. Her figure — or at least her name — now functions as a cultural code, recognizable even to those who have never set foot in Ise or read the Kojiki. In anime, video games, and films, the motif of Amaterasu is sometimes treated with reverence, but often freely reimagined — and, at times, even playfully or ironically.

“Naruto” — the Goddess’s Black Flames

In Naruto, the second most popular anime and manga series after Dragon Ball, Amaterasu is the name of a powerful ninja technique. It manifests as black flames that never extinguish until they have completely consumed their target — metaphorically echoing the divine light that both illuminates and devours all. The character Itachi Uchiha wields this ability as his ultimate weapon. While the narrative does not delve into religious detail, the very name operates as an instant cultural signal: in Japan, it immediately evokes associations with absolute divine power.

“Ōkami” — Amaterasu as the Wolf Goddess

In the game Ōkami (Capcom, 2006), Amaterasu appears in perhaps the most creative reinterpretation of the myth. The player takes on the role of a white wolf — the incarnation of the sun goddess — tasked with restoring balance and light to the world. The game is a remarkable fusion: landscapes styled after Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints, music inspired by gagaku court compositions, and countless references to the myths recorded in the Kojiki. Ōkami has achieved cult status and is still regarded as one of the most artistically significant video games ever created about Japan.

“Smite” — the Goddess in the Battle Arena

In the popular MOBA game Smite, Amaterasu appears as one of the playable gods. Her design merges classical shintō motifs — stylized armor, radiant beams of light — with fast-paced, action-driven gameplay. Here, she is depicted as a warrior goddess, blending sacred imagery with dynamic power.

“Persona 4” — Amaterasu as an Archetype of Power

In the Persona series, which intertwines Jungian psychology with Japanese symbolism (more about the game here: Japanese Folklore in Shin Megami Tensei: Playing Persona in the Rhythms of Shinto), Amaterasu is the name of the ultimate, fully awakened form of the character Yukiko Amagi’s Persona. This reference is subtle but potent: the goddess who “regains her light” becomes a symbol of discovering one’s true identity. It resonates on a deep psychological level with Yukiko’s personal narrative arc, underscoring themes of self-realization and autonomy.

In contemporary popular culture, Amaterasu functions as an archetype: sometimes embodying raw, overwhelming energy; sometimes appearing as a protective goddess; and, at other times, surfacing with an ironic, knowing smile. In fantasy literature, goddesses inspired by Amaterasu frequently emerge, while in Japanese cosmetic advertising, her name is often used to suggest “flawless radiance.”

Interestingly, Amaterasu increasingly appears in Western pop culture as well — for example, in Neil Gaiman’s American Gods and its television adaptation, where she is portrayed as one of the deities “living among humans” in the modern world. Amaterasu, then, operates within two parallel spheres: within Japan, she remains part of ritual, collective memory, and national identity; while in global pop culture, she functions as a universal symbol of light, power, and divine energy, detached from her strictly religious context.

The Long Journey of Light

Yet Amaterasu is not merely a figure from distant antiquity. She still lives — in the rituals of Ise Jingū, in imperial ceremonies, in school textbooks, in popular culture, and in everyday language. Her mirror, the Yata no Kagami, remains one of the Three Sacred Treasures of Japan, yet it is also more than that: it is a symbol of the unending question of identity — both collective and personal.

Perhaps this is why Hiratsuka Raichō saw in Amaterasu more than a goddess — she saw an archetype: a light that can be lost but always reclaimed. Her words, “In the beginning, woman was the Sun,” are not only a manifesto of emancipation but also a call to autonomy, one that transcends questions of gender or politics.

In the myth of the goddess hiding in the cave, each of us can find ourselves: in moments of withdrawal, in losing our voice, in standing in shadow. And each of us can also find the path back — to our own radiance. For Amaterasu, though a goddess for centuries, continues to teach us that light is never something granted once and for all. It is something to be rediscovered within ourselves — each time, anew.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Born in hell, buried in Jōkanji – what have we done to the thousands of Yoshiwara women?

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Amaterasu Supports Modern Meiji

Amaterasu Supports Modern Meiji The Manifesto

The Manifesto The Cave as a Metaphor of Exclusion

The Cave as a Metaphor of Exclusion