The Tragedy of Izanami and the Fury of Izanagi in the Land of Decay – In Japanese Creation Myths, Death Always Wins

The Japanese Creation Myth: A Tale of Loss and Irrevocable Passing

(The following story is known from many sources in Japanese culture, but its primary and oldest version is found in the Kojiki, compiled in 712 by Ō-no Yasumaro at the order of Empress Gemmei.)

Act I – Beginnings

Act I - Story

Kotoamatsukami – The Primordial Gods

The gods observed this undeveloped world and decided to bring order to its chaos. To accomplish this, they brought forth **two divine beings—**Izanagi and Izanami, the first celestial pair, whose destiny was to complete the act of creation.

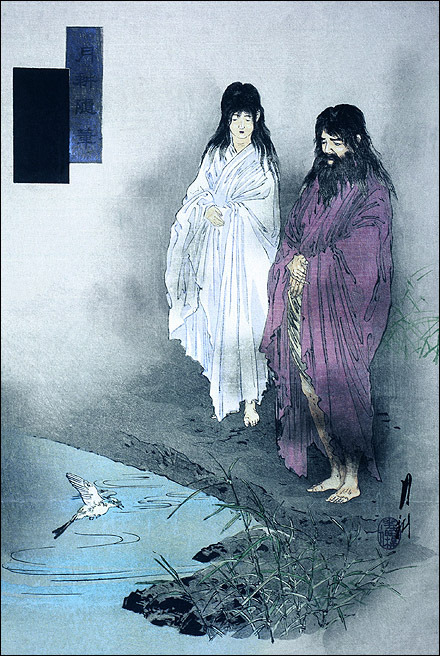

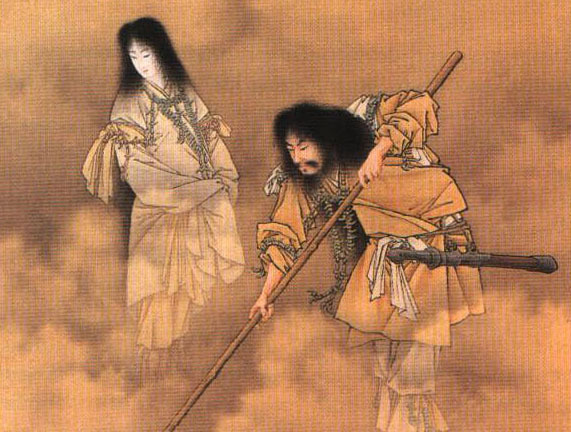

Izanagi and Izanami – The Divine Creators

— Let the land take shape beneath our will, Izanagi declared, gazing down at the swirling chaos below.

The gods gifted them the Ame-no-Nuboko (天沼矛), a sacred spear with a blade gleaming with the radiance of the heavens, so they could sculpt the world. Izanagi lifted the spear and dipped its tip into the turbulent ocean of chaos. As he withdrew it, **drops of water fell from the blade, thickening and swirling, solidifying into the first land—**the island of Onogoro (淤能碁呂島), "The Self-Forming Island."

Onogoro – The First Land and the Sacred Pillar

Awestruck by their creation, Izanagi and Izanami descended onto Onogoro, stepping upon the newborn earth for the first time. To make it their home, they erected a sacred pillar—Ame-no-Mihashira (天の御柱), "The Heavenly Pillar"—around which they would perform the sacred wedding ritual to unite their divine essences.

The Ceremony

Their hearts beat strongly, for they were not only to complete the act of creation, but also to join their souls and bodies in divine harmony. They decided to perform the sacred wedding rite by circling the pillar in opposite directions—Izanami walked one way, and Izanagi the other. When they met on the other side, Izanami spoke first:

But at that very moment, the divine winds held their breath, and the gods of the heavens furrowed their brows. Something had gone wrong.

According to the celestial order, it was the man who was supposed to speak first—such was the eternal law of the heavens. Unaware of their mistake, Izanagi and Izanami completed the ceremony and proceeded with the act of creation. Soon, their union bore its first child.

But when they gazed upon it, they were struck with dread. The child was deformed, unnatural—neither god nor human. They named it Hiruko (蛭子), "The Leech Child," and with heavy hearts, set it adrift upon the waves, letting the ocean carry it away into the unknown.

Shaken and sorrowful, Izanagi and Izanami prayed to the elder gods, seeking answers. The divine voices echoed from the heavens:

— You have performed the sacred ritual incorrectly. The man must speak first. Repeat the ceremony properly, and your children will be powerful and divine.

— How beautiful and noble you are, my wife!

And Izanami replied with a gentle smile:

— How handsome and strong you are, my husband!

This time, their souls united in accordance with the celestial law, and from their union, mighty deities were born—gods of the seas, rivers, winds, mountains, and forests. Their children were also the islands—one by one, like jewels scattered across the ocean, Awaji, Shikoku, Oki, Kyūshū, and Honshū emerged, forming the land that would later be called Nihon (日本)—"The Land of the Rising Sun."

Yet, as Izanagi and Izanami gazed upon their creation, filled with joy unlike any they had ever known, they remained unaware of the tragedy that awaited them—one that would forever change the fate of the world.

Act I – Commentary

Another essential aspect of this myth is the importance of ritual and its correct execution. Since ancient times, rituals in Japanese culture have not been mere symbolic gestures—their effectiveness depended on precise adherence to rules and the maintenance of spiritual harmony. If a ritual is performed incorrectly, it does not yield the desired results. This is why Izanami and Izanagi must repeat the ceremony—it is not enough to have intent; alignment with the cosmic order is required. This mindset persists in Japan to this day, from Shintō purification rites to everyday practices where form, precision, and spiritual engagement are crucial. This can be seen in martial arts (budō), the tea ceremony (sadō), and ikebana, where technique and spiritual harmony are inseparable.

It is also impossible to overlook the social implications embedded in this myth. The fact that Izanami spoke first and that this was considered a mistake reveals the gender hierarchy in ancient Japan. Although Izanami is a goddess of immense power, her initiative in the sacred ritual is deemed a disruption of cosmic order. This does not mean, however, that women in Japanese mythology were passive—quite the opposite. Izanami ultimately becomes a powerful goddess of death, and their daughter, Amaterasu, ascends as the supreme deity of the heavens. This myth not only reflects the patriarchal structure of early Japanese society but also illustrates a more nuanced philosophy of balance between masculine and feminine forces—neither can act in isolation, and harmony emerges only when each element finds its rightful place within the perpetual cycle of order and chaos. Nonetheless, the couple is punished simply because the woman spoke first. This theme will unfortunately become increasingly apparent throughout the following centuries, persisting even into modern history.

Act II – Tragedy

Act II - Story

Act II - Story

The world that Izanagi and Izanami created began to flourish. Their divine children filled the land and sky, giving form and life to nature. The fruits of their love took the shape of gods of the seas, mountains, rivers, and winds—each one an elemental force that would forever govern the world. Izanami gave birth to Ōyamatsumi (大山津見神), the deity of the great mountains, whose peaks would become the axis of the world, the stable foundation of all existence. Meanwhile, Watatsumi (綿津見神), the god of the seas, brought forth water, which cascaded into valleys, filling the land with rivers and lakes. Each of these children was an essence of the world itself, binding the heavens, earth, and waters into a single unity.

Izanami looked upon her divine offspring with joy, but she also grew weaker. With each new child, her strength waned—the more beautiful the world became, the more it drained her life force. And then, at last, it was time for the final child—a deity that would change everything.

Fire and Death

Izanagi knelt beside his beloved, cradling her trembling body. Her breath grew weaker and weaker, her gaze dimmed like the last flickering of an oil lamp before the wick burns out. And when the final sigh escaped her lips, the earth trembled once more—but this time, it was not the sign of new life, but the first death in existence.

At that moment, the world ceased to be a pure realm of creation. With Izanami's death, decay, transience, pain, and endings entered the fabric of reality.

Izanagi’s Wrath and the Bloodshed of a God

There was no trial, no doubt. Kagutsuchi, his own child, had become the enemy. He was fire—the force that had consumed Izanami. With one mighty stroke, Izanagi raised his sword and cleaved Kagutsuchi into pieces.

But the blood of a god is unlike that of mortals—from every drop of Kagutsuchi’s divine blood, new deities emerged. Eight mighty gods were born from his spilled essence, beings connected to the forces of storms, thunder, fire, and war. They were children of wrath, destined to bring both destruction and renewal, for in the world of the gods, every death gives birth to something new.

Yet none of these new deities could return Izanami to life. Her soul had vanished from this world. She had departed to a place where no one had ever gone before—Yomi, the realm of shadows, from which no one had ever returned.

Izanagi, the creator of light and life, now stood alone, consumed by grief for what he had lost. He refused to accept this fate.

He made his decision. He would descend into Yomi and bring Izanami back.

Commentary on Act II

Fire, which creates, is the same fire that destroys; life, which flows, is always moving toward death. This philosophy—where destruction is as fundamental as creation—permeates Japanese culture, from the fleeting beauty of ume and sakura blossoms to Shintō purification rituals following disasters.

Act III – The Descent into Yomi

Act III - Story

With his sword at his side and a resolve sharper than its blade, he set out for Yomotsu Hirasaka (黄泉津平坂), the narrow stone path leading to the underworld. The air grew heavier, thick with the acrid stench of rot. His footsteps sounded louder, their echoes unnaturally hollow. There was no wind anymore, no sky. Only the road—the road leading downward.

Deep down…

No one should walk this path…

Yomi – The Land of No Return

What they called Yomi (黄泉) was not a place of torment or fire.

It was far worse.

The darkness was so thick it seeped into his eyes, as if light had never existed.

Is this what death looks like? Izanagi thought.

A time that doesn’t pass.

And then, after what could have been a moment or an eternity, he saw her.

Izanami.

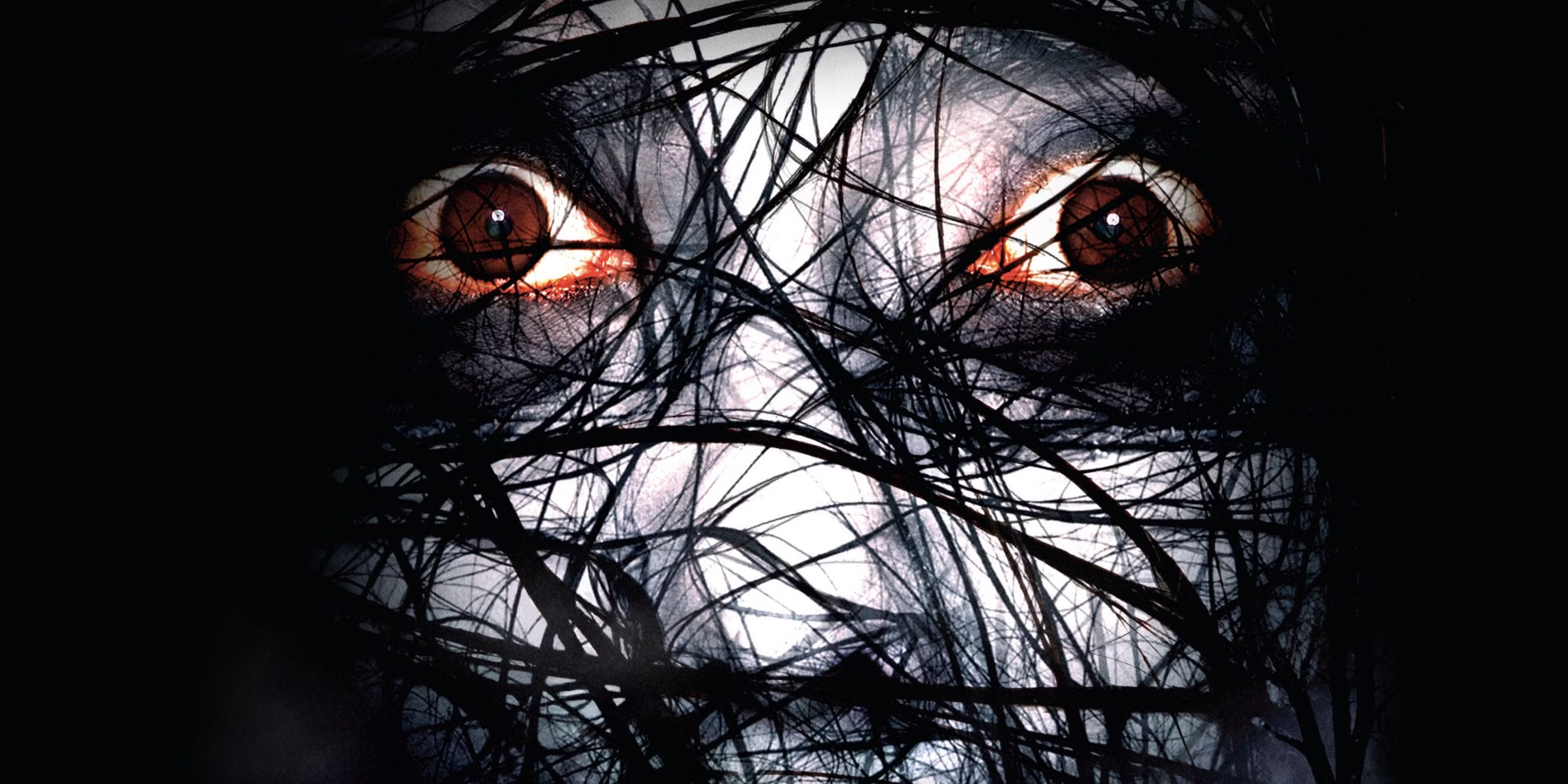

She stood before him, veiled in darkness, just as he remembered her, and yet…

not the same at all.

She was here, and yet her presence felt blurred, as if she no longer belonged to the world he knew.

“Izanami!” His voice rang unnaturally loud, vibrating in a space that should not have been able to hear him.

For a moment, he thought he saw the shadow of a sad smile on her face.

“I wish I could return,” she answered, her voice soft but not weak.

“But it is too late.”

Izanagi frowned.

“It cannot be too late. I am here. I will open the way for you.”

“You don’t understand…” Her voice sharpened. “I have eaten the food of Yomi.”

Izanagi froze.

I have eaten the food of Yomi.

Those words struck him like a blade he could not parry. The law was absolute—those who consumed the underworld’s food belonged to the underworld. They could never return.

Izanami stared at him for a long moment before speaking again.

“But since you have come… I will ask the rulers of Yomi if I may leave. Wait for me. But promise me one thing—you must not look. Do not enter. Do not seek me in the darkness.”

Do not look.

Do not enter.

Do not seek.

Izanagi nodded. There was no other choice.

The Forbidden Glance

Izanami disappeared into the depths of the void, and Izanagi was left alone.

The silence around him was suffocating, thick and unnatural. The air was dead, and even breathing it felt like a violation.

And waited.

And waited.

But how long can one wait in a place where time does not exist?

Izanagi was not human, not mortal—he was a god. But even gods have limits.

What if this was a trick?

What if Izanami was never coming back?

What if death truly was eternal?

He could not stand the darkness anymore.

Not here.

Not among the things that lurked, shifting unseen in the void.

He broke his promise.

In the blackness, he reached into his hair, broke off a tooth from his comb, and pressed it to the ground.

The wood ignited.

And then, he saw her.

But this was not Izanami.

And when she opened her mouth,

she screamed.

Commentary on Act III

Act IV – The Escape from Yomi

Act IV - Story

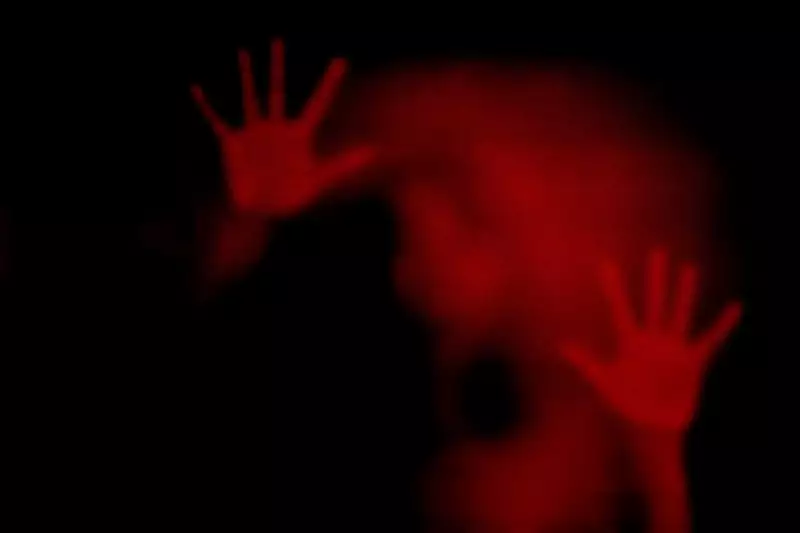

This was not the cry of a woman.

This was the howl of the goddess of death.

In an instant, the darkness moved.

Something stirred—quickly, unnaturally, as if the very void that filled Yomi had begun to seethe, violently convulsing.

Izanagi ran.

He had to stop them. He reached into his hair, tore out his comb, and flung it behind him—within seconds, the comb’s jagged teeth transformed into towering bamboo shoots, swelling, bursting with thick, resinous sap, bending under their own weight.

The yomotsu-shikome pounced like starving beasts, clawing, gnawing, tearing.

Izanagi ran on.

The shadows behind him shifted. Izanami had sent more—warriors of Yomi, 1,500 dead souls whose bodies would never decay, doomed to serve the darkness forever.

Izanagi drew his sword and slashed through the air—he did not strike any of them directly, but his fury tore through the very fabric of Yomi.

He ran.

He ran toward the light, though he could not yet see it—only feel it.

And then, at last, he saw it—the border between worlds, a thin fissure between shadow and existence, between being and nothingness.

It was Yomotsu Hirasaka (黄泉津平坂), the threshold of Yomi, where the boundaries of reality were so thin they could be torn apart with a single motion.

Izanagi lunged forward.

Death was right behind him.

But he was faster.

The darkness struck the stone.

Unseen hands, voices, fury—all of it crashed against the barrier.

And then, Izanami spoke.

Her voice was calm now—cold.

"If you have abandoned me, my dear husband… then let 1,000 people die in your world every day."

Izanagi clenched his teeth.

He had nothing left to say.

He had no more Izanami.

But he had the world.

"Then… 1,500 people will be born every day."

That was the last thing they ever said to each other.

There was nothing left to say.

The Ritual of Purification and the Birth of New Gods

The air was clean, yet he could still smell the stench of death on his own skin.

He had to purify himself.

He descended into the river and submerged himself—this was not a simple cleansing, but the first harai (祓), a ritual of purification that would later become a cornerstone of Shintō.

But Yomi did not let go so easily.

As Izanagi washed his face, from his eyes and nose, new gods were born.

From his left eye—Amaterasu (天照), the radiance of the sun.

From his right eye—Tsukuyomi (月読), the tranquility of the moon.

From his nose—Susanoo (須佐之男), the rage of the storm.

They were to rule the world now.

But Izanagi’s role was over.

He had crossed the threshold of death, seen the realm of shadows, and could never forget it.

It was not he who would rule the world of the living now, but the new generation of gods.

Commentary on Act IV and Conclusion

Izanagi, in his rebellion against death, tried to break this order—he wanted to reclaim what was lost.

But in the end, he had to accept that some things cannot be undone.

The sealing of Yomi and Izanami’s curse marks the first instance in Japanese mythology where the cycle of life and death is established. The myth justifies the eternal order of existence—people die, but they are also born, and death and birth become two equal forces. This concept is deeply ingrained in Japanese philosophy—from the melancholy of mono no aware to the belief that destruction always brings something new.

And so this story ends—not with triumph over death, but with the realization that the world exists only because there is a balance between light and shadow—one that no one can break.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Vengeful Cat Demons in Japanese Legends: The Sinister Bakeneko

The Aokigahara Suicide Forest: What Secrets Do the Silent Trees Guard?

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Act II - Story

Act II - Story