What Does “Shōgun” Really Mean? One word that forged the Japan of samurai in steel and blood

A land where warriors subdued emperors

In the shadow of the Fujiwara’s purple sleeves, amidst incense-scented temple corridors, a parallel civilization began to take root: men in heavy armor traded parchment for iron and composed their own verses on loyalty, shame, and revenge. The aristocracy treated them as tools, failing to notice the moment when the tool gained consciousness—and demands. No one realized it at the time, but Japan was about to change the course of its history forever. The samurai class was being born—a warrior with his own honor, his own sword, his own values, utterly alien to the aristocracy. Time passed, and increasingly daring uprisings weakened the emperor’s power. Until at last came Minamoto no Yoritomo, the first shōgun with absolute power, forging the first “field tent” government in Kamakura. The centuries that followed brought astonishing changes, ultimately drowning the Japanese Islands in an ocean of blood during the endless conflagration of the Sengoku era—here, the sword was the only currency in the scorched landscape of Japan. Finally, Tokugawa Ieyasu tamed the chaotic hosts and, in the silence of Edo, enclosed the entire archipelago in his iron grip—reviving a title abandoned for generations: Shōgun. Thus, from a temporary designation emerged the very backbone of Japanese history.

Today’s article tells the story of a single word that forged the destiny of an entire nation. We will begin at its roots—breaking down the kanji 「将軍」, uncovering its etymology and place in the Sinocentric order, and then move through centuries filled with battles, betrayals, and unexpected downfalls. We will trace the path from the campaigns of the first sei-i taishōgun against the Emishi, through the birth of the samurai ethos, to the first shōgun wielding absolute authority. Then, we will plunge into the heart of the Sengoku storm and see how a world steeped in blood gave rise to the Tokugawa shogunate, whose iron will turned Japan into a perfectly regulated mechanism. So let us embark on a journey through centuries of war, betrayal, and startling twists.

Shōgun

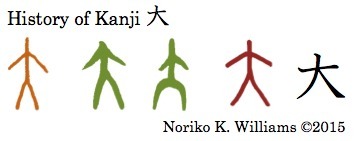

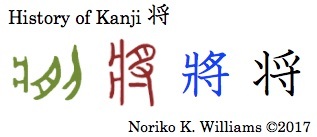

What We Can Read in the Characters 将軍 (shōgun)

The first character, 征 (sei), means “conquest,” but not only in the physical sense. It also signifies a march, an expedition whose goal is subjugation—in the name of greater order. At the core of its ideographic root lies both violence and mission. The second character, 夷 (i), means “barbarian”—though not necessarily someone wild, but rather someone outside the borders of the realm (read more on this here: Forgotten Wars of Ancient Japan – The Emishi Versus Yamato). For the Yamato court in Nara and Heian, these were above all the Emishi—northern peoples who had not submitted to the culture of writing and ritual. Together, sei-i is the “subjugator of barbarians”—one who leads an expedition not for glory, but to “enforce civilization.”

Before we move on to the periods where most of us are familiar with the term shōgun—whether the legendary Minamoto or the austere Tokugawa—let us look at its beginnings, which are not always remembered, but are equally fascinating.

The First Shōguns in History

Ōtomo no Otomaro – The First Shōgun

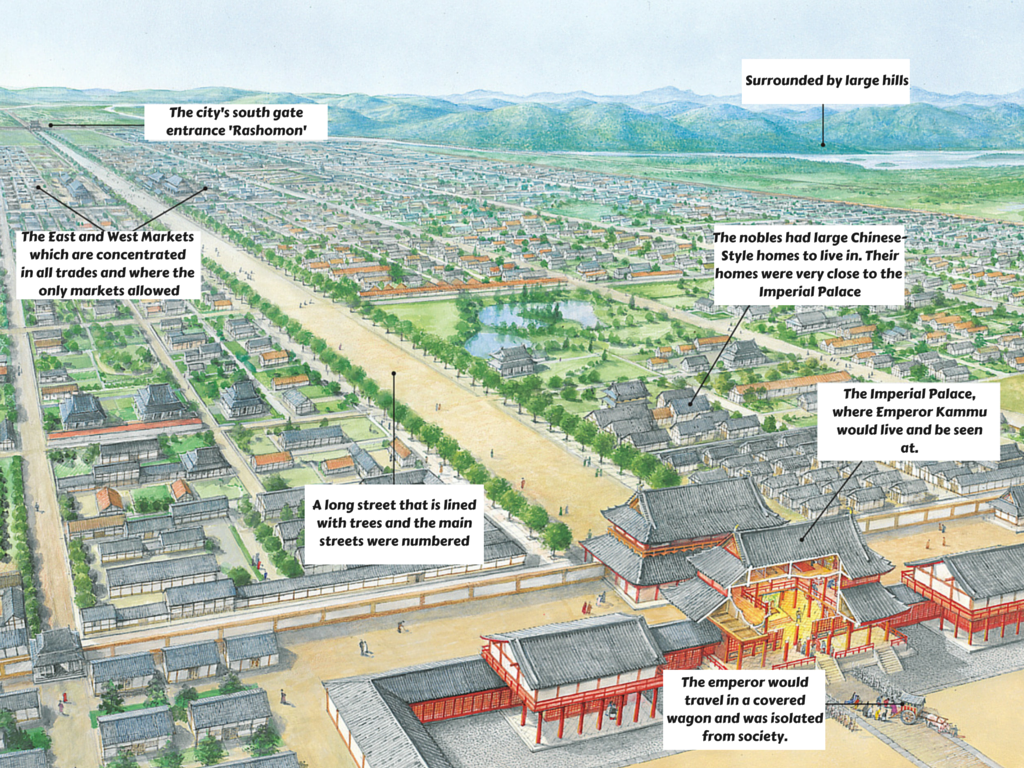

Otomaro’s campaigns were brief—two hot seasons during which the ritsuryō army marched heavily armored, while the Emishi avoided open battle. When envoys brought word to Heian-kyō of the first submissions by chieftains of the Isawa tribe, Emperor Kanmu publicly removed Otomaro’s armor and restored his courtly robes—a gesture underscoring the temporariness of the title. The shōgun departed from the field, and full authority once again resided with the throne.

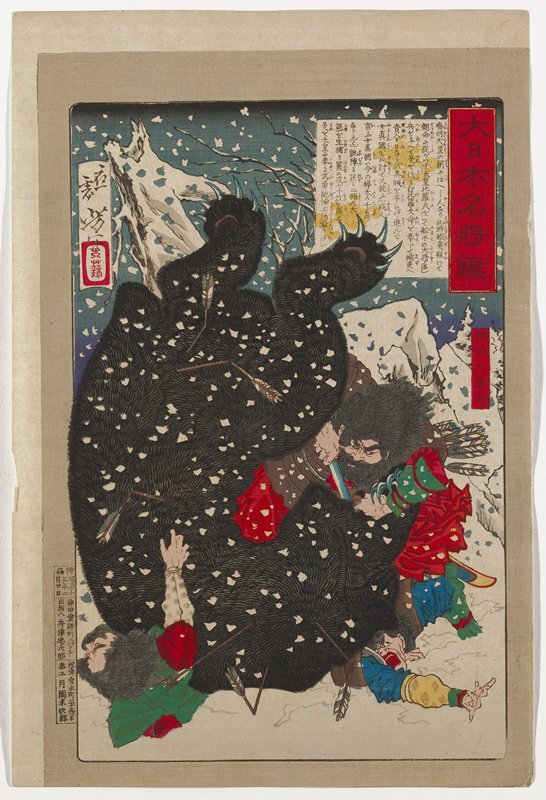

Sakanoue no Tamuramaro – Warrior-Priest in Bearskin

Tamuramaro combined ruthless tactics—swift cavalry, mobile palisades, winter raids—with subtle diplomacy. He sent swords and silk to Isawa, established garrisons that grew into farming settlements, and eventually the Emishi leader Aterui stood before him in 801, offering a truce. Legend says Tamuramaro wished to spare Aterui, moved by his courage and honor; but the court ordered the captives beheaded in the capital, to forever break the spirit of the north. With this execution, the shōgun’s first mission was symbolically concluded. Tamuramaro received a palace in Kyōto, courtly ranks, and—paradoxically—was sent into the shadows, like a sword returned to its saya when peace arrives.

A Military Official, Not a Ruler

Fujiwara

Heian – Where Temple Scents Blend with the Smell of War

Thus, when in the 9th century new local uprisings broke out—whether due to excessive taxation or clan feuds—the emperor repeatedly reached for the old formula of sei-i taishōgun. The title was meant to act like lightning: swift, blinding, instantly paralyzing resistance. The very sound of the word taishōgun froze the blood of rebels; the sight of troops under that banner robbed them of courage and reason. The power concentrated in one man—military, and in the eyes of the people, also moral and spiritual—carried within it a seed of threat. The emperors sensed it from the beginning; even Kanmu, personally removing the armor of the first taishōgun, knew what a perilous bargain he had struck with fate.

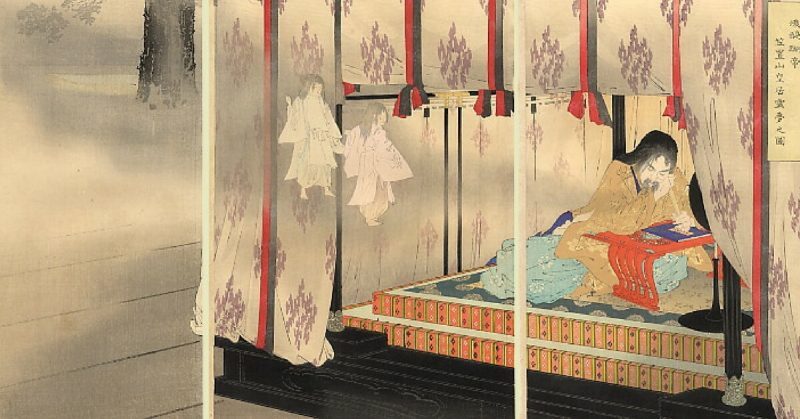

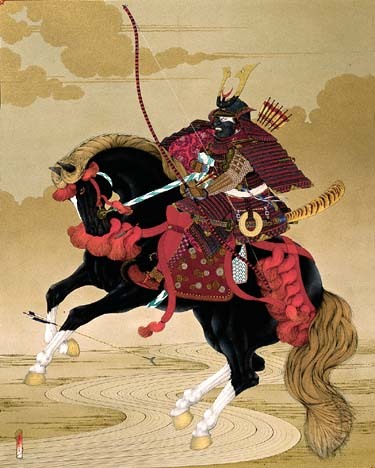

Decades passed, and the mercenaries of the northern fields became men of the sword and of honor, developing a code entirely different from the etiquette of the aristocratic court. We witness the birth of a new culture within the same linguistic sphere—a samurai culture. Thus, in an era we mostly remember through the lens of temple roofs, poetry contests, and the rustle of silk, something entirely different was ripening: the seed of an independent warrior class. For now, it existed only as a shadow—still bowing before the emperor’s purple robe. But a shadow grows when the sun is low: it needed only a few more centuries to envelop all of Japan.

Taira

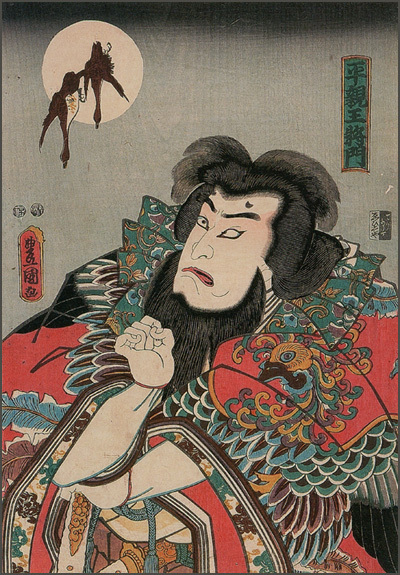

Darkness Before the Storm – Taira no Masakado and the First Defiance

Darkness Before the Storm – Taira no Masakado and the First Defiance

One misty autumn morning in the year 939, the long, silent waves of the Tone River lapped against the forests of Shimōsa Province as Taira no Masakado raised his own banner (more about his rebellion here: Ancient warrior, false emperor, vengeful onryō demon – Why does Taira no Masakado's grave stand in the very center of Tokyo?). On white silk there was no imperial lily crest, but a black character taira—“peace.” Irony? Or perhaps a forewarning of the bloody silence that seizes the air before a storm. Masakado, descendant of a collateral Heian line, broke with the old order: he declared the ancient eastern land of Kantō a “new court” and took the title Shinnō—“New Emperor.” For the first time since the founding of Heian-kyō, someone dared to say aloud what the eastern provinces had whispered for years: the land we live on has no need for court poets or Fujiwara purple—it can govern itself.

Who Were Masakado’s Warriors?

Who Were Masakado’s Warriors?

They were not yet samurai in the later sense—they knew nothing of tea or Rikyū’s death, nor of the code that centuries later would be compiled by Yamamoto Tsunetomo. They were gōzoku: armed farmers, owners of rice fields and horses, who planted seedlings in the summer and reached for the bow in autumn. The Taira clan granted them fiefs in exchange for guarding trade routes, and when the court raised taxes, it was they who raised their spears. Here, at the boundary between dense reeds and sandy plains, a new caste was being forged—men of the sword, but also of the land; lords who needed no imperial script to legitimize their power.

A Rebellion That Became Legend

The court summoned loyalist clans to arms—Taira no Sadamori (Masakado’s cousin by blood) and Fujiwara no Hidesato. Under the banner of a two-headed phoenix, they marched through winter storms to confront the rebel. The Battle of the Sumida River was short but violent; fire arrows set dry grasses ablaze, the wounded cried out, horses tore up the mud. Masakado fell—according to legend, a bolt of lightning struck his skull, as if the heavens themselves denied the seal of legitimacy to a self-proclaimed monarch. His head was impaled atop a bamboo stake and denied prayers at Kanda Myōjin—the mighty kami of war, who from then on would gaze upon it with horror.

Masakado became for future generations both a warning and an inspiration: a spirit of vengeance, but also a patron of those bold enough to dream of an alternative Japan—one without central oversight, where the sword carried as much weight as the brush of a court bureaucrat.

A Herald of a New Era

In the palaces of Heian-kyō, people still sang of spring mist and plum blossoms, but amid the poems, the pillars of the old world began to crack. A time was coming when the sword would no longer be merely the arm of the throne. And when the next flash split the sky above Japan, it would not fade after the storm.

Taira no Kiyomori – An Aristocrat in Armor

An Alliance of Sword and Throne

An Alliance of Sword and Throne

Kiyomori understood that court titles were like empty shells unless backed by armed clients and money. After defeating the Minamoto clan during the Heiji Rebellion (1159), he made three moves that shook the old aristocracy:

#1 – Marriage and Blood: He married off his daughter Tokuko to Emperor Takakura; their son, an infant named Antoku, became heir to the throne. In an instant, the Taira became the imperial family.

#2 – Trade and Gold: He built a port at Owada-no-Tomari (present-day Kobe) and a network of watchtowers controlling the Shimonoseki Strait. Customs duties from Chinese trade filled the private coffers of the Taira—the Fujiwara could only count the losses and gnash their teeth (it was, effectively, the end of their centuries-long dominance).

#3 – Temples and Prestige: He funded the expansion of Itsukushima on Miyajima Island; the red torii gates in the sea became the calling card of Heishi (Heishi, or Taira 平氏, used interchangeably). The sea goddess Benzaiten henceforth blessed the Taira fleet, uniting divine favor with control of the shipping lanes.

The Warrior Who Seized All Power

And yet the aristocracy itself increasingly needed protection on its way to temples or estates; Kyoto was teeming with Kiyomori’s soldiers. In the half-century since Masakado’s rebellion, a new balance of fear had emerged: the throne depended on the swords of warriors, and the warriors on the court’s tribute chests. Now the salons smelled of both agarwood incense—and steel.

The Road to Kamakura

Minamoto no Yoritomo (his name will be remembered!), son of the defeated Yoshitomo, was just ending his twentieth year of exile in Izu. Upon hearing of Mochihito’s imprisonment, he seized the white banner bearing the mon of the Minamoto clan and called the Kantō clans to arms. In a short proclamation, he promised to “restore the ancient laws”—but in truth, he promised a world in which the sword would never again bow to silk. His speeches, his actions—everything already breathed a completely new world. For decades, a distinct warrior class had been forming—but it is in the words and deeds of Minamoto no Yoritomo that we see it was now ready to seize power—not just administrative, but cultural. The samurai class had been born.

Kiyomori is said to have laughed when he received reports of the young Minamoto: “A swallow pounces on an eagle!” But he died suddenly in the winter of 1181, clutching his fevered arm and calling for monks to curse the Minamoto clan for seven generations. The curse proved useless. The mighty Taira ships still slid across the waters of the Seto Inland Sea, but the machine was now without its captain.

In old Kyoto, beneath snow-covered rooftops, Fujiwara courtiers looked at one another in silence: a warrior without a title had managed to seize the court; would a warrior with a title not manage to seize all of Japan? In the east, Yoritomo was raising palisades over Sagami Bay. The sky grew heavy, the silence rang in one’s ears—and the storm approached. No one had ever seen such a storm...

Minamoto

The Birth of the Shogunate – Minamoto no Yoritomo and Kamakura

Then came the spring of 1185 and the strait of Dan-no-ura, where the Taira fleet under red banners clashed with the white onslaught of the Minamoto. The young emperor Antoku, cradled in the arms of his grandmother Tokuko, leapt into the sea to avoid capture. In a single moment, the waters swallowed him—and with him, the old order was consumed. The bodies of warriors, weighed down by bronze armor, quickly sank to the depths of the strait—only white fans and broken taiko drums floated on the waves. At that moment, the sword ceased to bow to silk. And it would not do so again for nearly a thousand years.

Yoritomo – General–Architect

Yoritomo – General–Architect

Minamoto no Yoritomo entered Kamakura not only in triumph but bearing scrolls and maps. Victory was not enough; he needed a system that could maintain control over thousands of scattered warriors. In 1185—just months after the naval battle of Dan-no-ura—he issued an edict deploying new officials across the provinces:

- Shugo (守護) – “guardians of peace,” military governors responsible for policing, recruitment, and suppressing uprisings.

- Jitō (地頭) – “heads of the land,” tax collectors and estate managers who recorded every sprouting stalk of rice.

1192, third year of the Kenkyū era. In the humid heat of the sixth month, envoys of Emperor Go-Toba crossed the Hakone mountains to deliver Yoritomo the title sei-i taishōgun. The warrior now officially became the “Great General for the Subjugation of Barbarians”—though no barbarians had appeared on the horizon for centuries, and the title, once a lightning bolt, now became a permanent lightning rod.

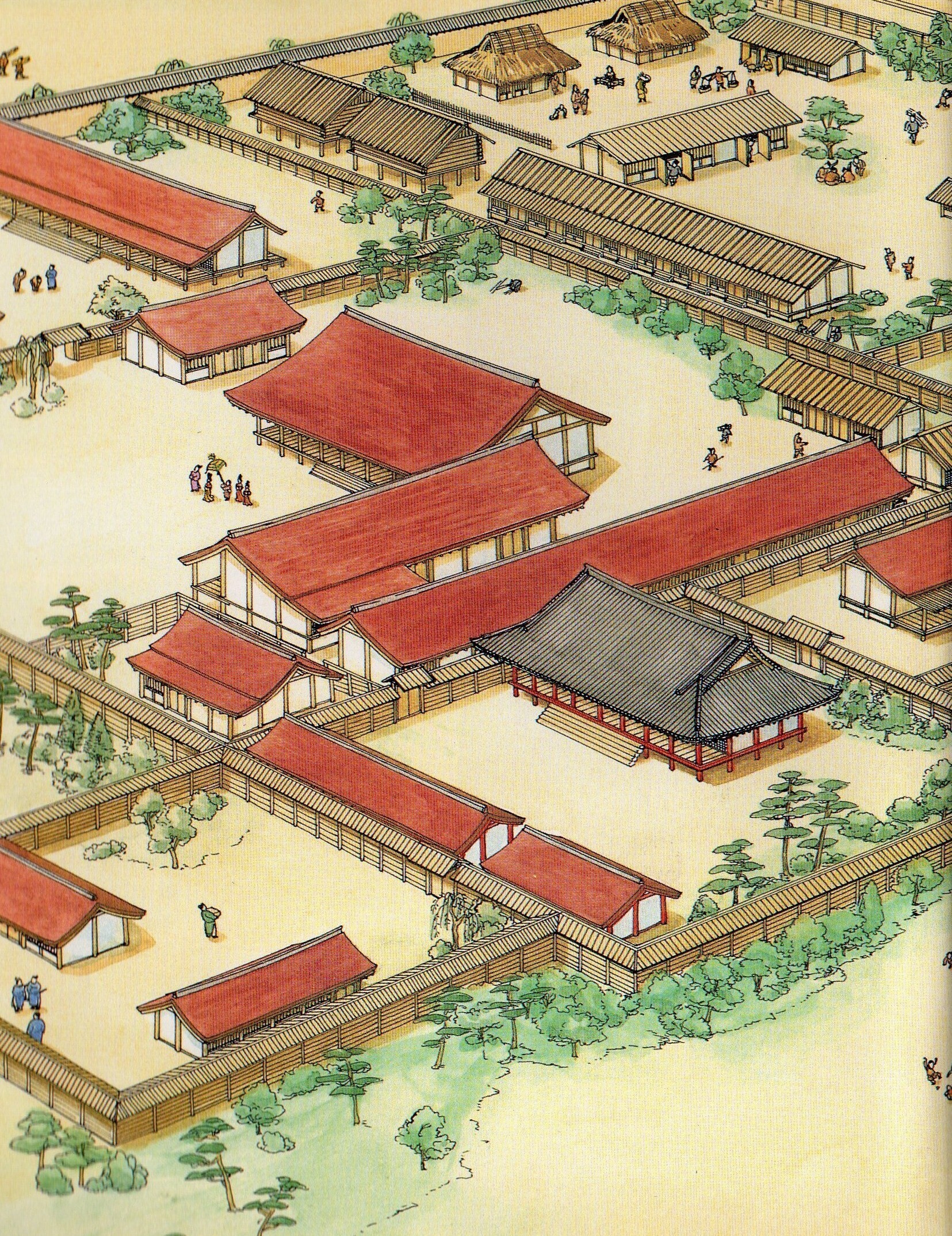

The imperial throne was to remain in Kyōto: the source of ritual, the calendar, and sacred authority. A symbol. In Kamakura, however, resided real power: the law of the sword, military orders, courts for samurai.

The court issued nengō (era names), but Yoritomo dictated who paid and who marched to war. The sun still rose over the emperor’s golden pavilion—but it was Kamakura that cast its shadow over the entire land.

Bakufu – Government of the Tent

The bakufu became a permanent “tent”: built of stone and wood, roofed with shingles, but never a palace draped in silks. In the dirty streets of Kamakura, the scent of smoked mackerel and horse manure rose—the scent of a new Japan, where armor was more common than the silk sleeves of a sokutai. Common? No—nobler.

The stillness of the court gave way to a new rhythm: the clatter of waraji sandals and the rattle of armor hanging above sleeping mats. Japan had entered a millennium of steel and honor, and though the sword still bowed to the heavens—it would never again bow to silk.

Puppets and Regents – How the Shōgun Lost His Power

Minamoto no Sanetomo—the second official shōgun—was a poet, not a commander. He composed waka, sang of loneliness and melancholy, not of strategy and war. Locked in the cage of Kamakura, he became a hostage to his own title. When his elder brother Yoriie was murdered, and Sanetomo himself fell victim to an assassination at the hands of his own cousin—the tragedy was complete. The Minamoto line was extinguished, and the title of sei-i taishōgun was handed to young princes from the distant imperial court—boys who had neither army nor authority. They were figures—called kubō—“heads” to which the Hōjō attached the rest of the body as they pleased.

The greatest test of this structure came in 1221 with the rebellion of Emperor Go-Toba—Jōkyū no ran. Seeing Kamakura’s weakness, the emperor attempted to reclaim power—but miscalculated. The armies of the shogunate marched into Kyōto and crushed his forces—and in the heart of the aristocratic world, beside the imperial palace, they established the Rokuhara Tandai office—a military garrison and secret police of Kamakura meant to watch over the imperial capital.

Everything had reversed. The emperor was exiled. Kamakura—once a remote military outpost—now ruled the country through a complex web of masks and proxies. The age of samurai rule was no longer a dream: it had become a mechanism. Quiet, effective, stripped of illusion. And precisely because of that—inevitably—anger began to accumulate within it. Power without a face stirs unease. And soon—from the provinces, from the mountains and fields—those would come who sought to break it. The weakness of power leads to one thing—someone stronger reaches for it. And what if there are many of them?

Sengoku

The Great Sengoku Reset – Collapse, Civil War, Attempts at Restoration

The military machine of Kamakura jammed from within. It was not a foreign invasion but internal ambition that would shatter the wall holding the country together. In the mid-14th century, Japan entered a period that cannot be described without words like “betrayal,” “schism,” “bloodshed.” For over one hundred and fifty years, the islands were immersed in boundless, all-consuming war—and it all began with a single decision.

Ashikaga Takauji—a descendant of the Minamoto clan and a general in Kamakura’s service—was sent to suppress the rebellion of Emperor Go-Daigo. But instead of destroying him… he defected. One night, without warning, Takauji turned his banners, crushed the Hōjō forces, and opened the gates to an imperial restoration—the Kenmu era (1333–1336), which aimed to restore imperial power after more than a century of samurai dominance.

But old Japan would not yield so easily. Emperor Go-Daigo fled south to Yoshino and declared himself the sole rightful ruler. Thus was born the Nanboku-chō period (1336–1392)—the era of “Two Courts”: the Northern (controlled by the Ashikaga in Kyōto) and the Southern (in the mountainous regions of Yoshino). Two Japans—two calendars, two eras, two systems of legitimacy. Brother fought brother, son battled father—every province, every castle was someone’s conquest or someone’s burning grave.

Ashikaga power rested on compromise and illusion—on support from the daimyō clans, who grew stronger and began to resemble independent kingdoms. Though Muromachi gained the trappings of a capital, it was only a theater—haunted by the shadow of mistrust behind every decision. Shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358–1408) tried to construct new majesty: he staged spectacular ceremonies, built the Golden Pavilion (Kinkaku-ji), established diplomatic ties with China, and dressed his rule in incense, lacquer, and silk. But it was only a silver thread—delicate, easy to snap. The system no longer had a central spine. It was no longer grounded in the sword. And samurai respected only the sword.

The country sank into an ocean of lawlessness. The Sengoku era began—the “Age of Warring States.” No law mattered anymore except the law of honor and clan loyalty. Samurai, born among ruins, knew only one thing: war. For three generations, children were not born for school, but for battle. They learned to tie axes, read maps, and fight from horseback. This was a Japan without a center—a thousand fortresses and not a single heart.

Oda

Power Without Title – Nobunaga and Hideyoshi

He was never shōgun—and never became one. For him, the title “Oda Nobunaga” was the only one worthy of his ambition. Yet it was he who opened Gifu Castle to trade with Europe, who modernized armies, introduced mass use of firearms, and even attempted to create a unified currency system. He needed no title to rule—his ambition was tenka fubu (天下布武): “To rule the realm by force of arms.”

When he fell—murdered by his own general, Akechi Mitsuhide, in the famous Honnō-ji Incident—Japan trembled. But it did not stop.

For then came the second of the great ones.

Toyotomi

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

He could not become shōgun—his lineage was unworthy. So he became kampaku (関白)—regent to the emperor. He took the surname Toyotomi, built a mighty castle in Ōsaka, and ruled with absolute authority. When he spoke, the daimyō fell silent. When he issued edicts—banning samurai from farming, forbidding peasants from bearing arms, prohibiting Christians from spreading their faith—the entire nation held its breath.

For Hideyoshi, titles were merely tools. He didn’t need them to govern—for he understood that hierarchy is only as strong as your sword, your allies, and your rice granaries. In that, he was a student of the great Nobunaga. Sadly—his reign was marked—again, historians still debate this—perhaps by madness.

When he died, he left behind no strong successor. The child meant to inherit his world was too young. And then—from behind the scenes, patiently, like a shadow behind a lantern—appeared the third. A brilliant strategist, a patient manipulator.

And he would become shōgun.

Tokugawa

The Return of the Shōgun – Tokugawa and a New World Order

Ieyasu and Sekigahara: Revenge Planned for Decades

Ieyasu and Sekigahara: Revenge Planned for Decades

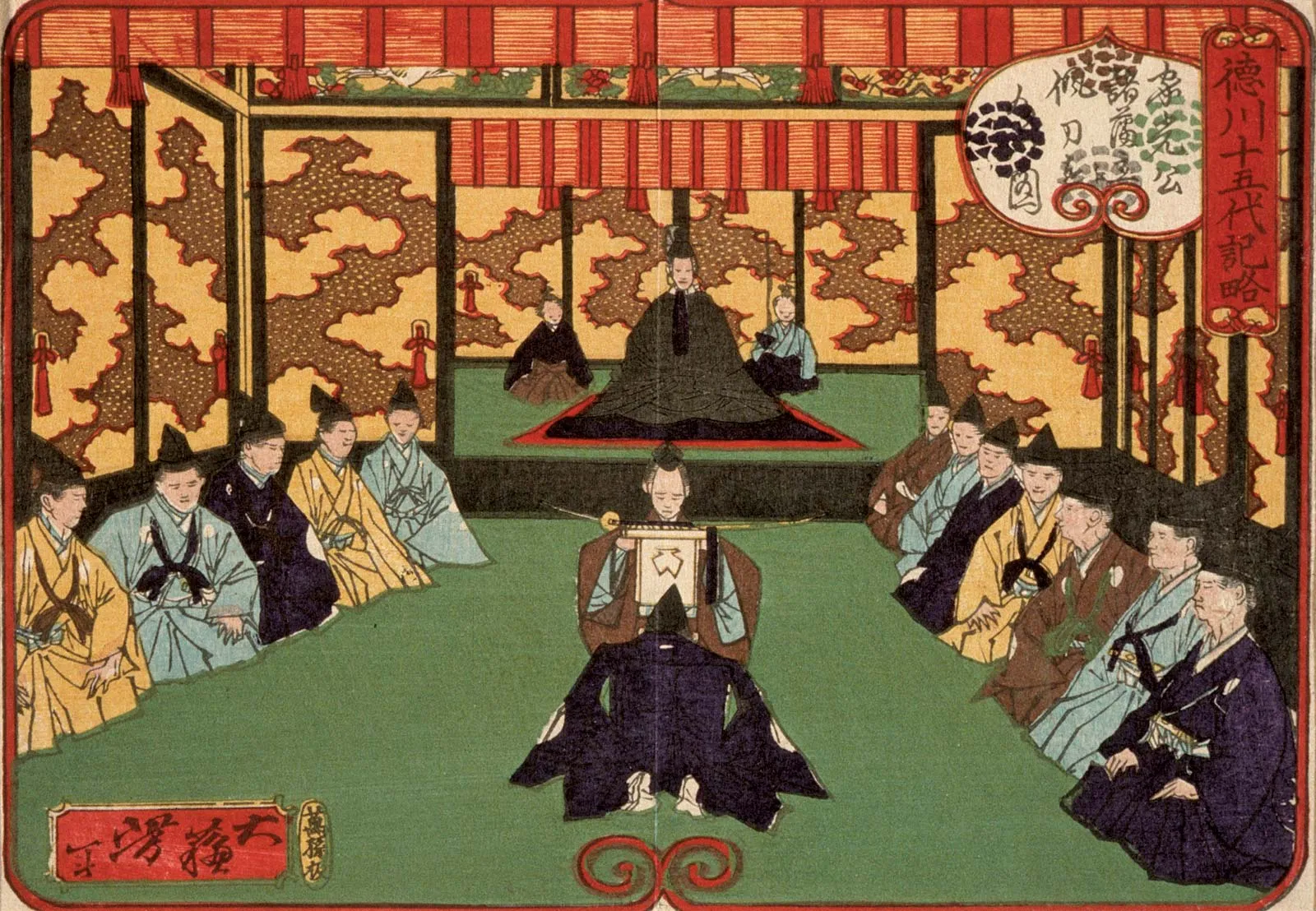

The 5th year of Keichō (1600)—a misty dawn in the valley of Sekigahara. The Western Army of Ishida Mitsunari, bolstered by the remnants of the Toyotomi, faces the Eastern Army of Tokugawa. Thousands of banners, the thunder of arquebuses, arrows falling like cold rain—but the key lies in a single name: Kobayakawa Hideaki. Ieyasu had bribed him beforehand with the promise of a domain. At noon, Hideaki betrays; his troops break through the Western flank, and Mitsunari watches as the numbers of victory slip from his grasp. The battle lasts barely six hours—but the sudden change of banner costs 30,000 lives. It is social engineering—not brute force—that wins Japan.

Two years later, Ieyasu receives in Kyōto the title sei-i taishōgun—for the first time in several generations—and moves the center of power to a small fishing town on the eastern coast… which he renames Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

The Shōgun as Father of the Nation, the Daimyō as Pawns

The shogunate issued an edict: “Let the peasant till, the samurai govern, the merchant trade.” Society was locked into four drawers—farmer, warrior, artisan, merchant—a new, immutable cosmic order.

Edo as a City of Power and Silence

The Sankin-kōtai System – Discipline Through Ritual

Ritual became a weapon subtler than steel: the cost of obedience turned into a tool of control. The “endless march” of sankin-kōtai turned a daimyō’s life into a machine of ceremony, in which every step was measured by the cadence of a drum.

Kōgi and Bakufu – The Masks of Absolutism

Tokugawa Ieyasu died in 1616, but his spirit never left the land of Japan. He was deified as Tōshō Daigongen—the divine guardian of Japan—and buried in a mountain sanctuary in Nikkō, from where he was to watch over the northern sky of Edo. Thus, a new legend was born: the shōgun not only ruled in life, but even after death—as a deity, whose shadow stretched over an entire era.

In the silence of Ninomaru Palace, amid the harmony of blooming plum trees, the Tokugawa chronicled a reign where the most important events were those that did not happen: no daimyo rebellions erupted, no civil war returned, no battle was fought. The sword rusted quietly in the scabbard of Confucian order.

Thus began the Pax Edo – long and golden, though woven from fear, surveillance, and a constant accounting of gains. And somewhere beneath that smooth surface, new forces matured: merchants wealthier than the daimyo. A sign of modernity – under every latitude. Over Edo rose a cloudless sun – and the shōgun, father of the nation, smiled, knowing all the pawns stood politely on their squares.

Meiji

Epilogue – The Twilight of the Field Tent

Thus ends the tale we began in the age of Yamato, when imperial troops marched north to subjugate the Emishi, and the title of sei-i taishōgun was carried on the blades of Tamuramaro and Otomaro. We witnessed how that fleeting flame became an enduring torch ruling the archipelago. Taira no Masakado was the first to raise his hand against the ancient order. Minamoto no Yoritomo turned the title of shōgun into the beacon of Kamakura and created the bakufu – the field tent government – which withstood many storms. Hōjō Masako and her regents concealed the light of that torch behind the layered veils of puppet rule.

The emperor once again sat on a visible throne, but the shadow of the shōguns remained in the culture: in the silence of zen doctrine, in the noble simplicity of the katana, in woodblock prints depicting the twilight at Sekigahara Valley and the moonlight over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge. For though the tent was packed away, its canvas still flutters in memory.

“Shōgun” is not just a historical term. It is the very spirit of Japaneseness – around which the axis of history has spun for centuries.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Kabukimono Longing for War: Free Spirits, Deadly Rogues, and Madmen in Women’s Kimonos

Kamikaze – Two Divine Typhoons of Life, One Grim Wind of Death

10 Facts About Samurai That Are Often Misunderstood: Let's Discover the Real Person Behind the Armor

Furuta Oribe – a ruthless killer and sensitive artist in the era of the Sengoku samurai wars

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Darkness Before the Storm – Taira no Masakado and the First Defiance

Darkness Before the Storm – Taira no Masakado and the First Defiance Who Were Masakado’s Warriors?

Who Were Masakado’s Warriors? An Alliance of Sword and Throne

An Alliance of Sword and Throne

Yoritomo – General–Architect

Yoritomo – General–Architect

Ieyasu and Sekigahara: Revenge Planned for Decades

Ieyasu and Sekigahara: Revenge Planned for Decades