The Hour of the Rat, the Koku of the Tiger – How Was Time Measured in Shogunate-Era Japan?

The Hour of the Rabbit, the Hour of the Dragon

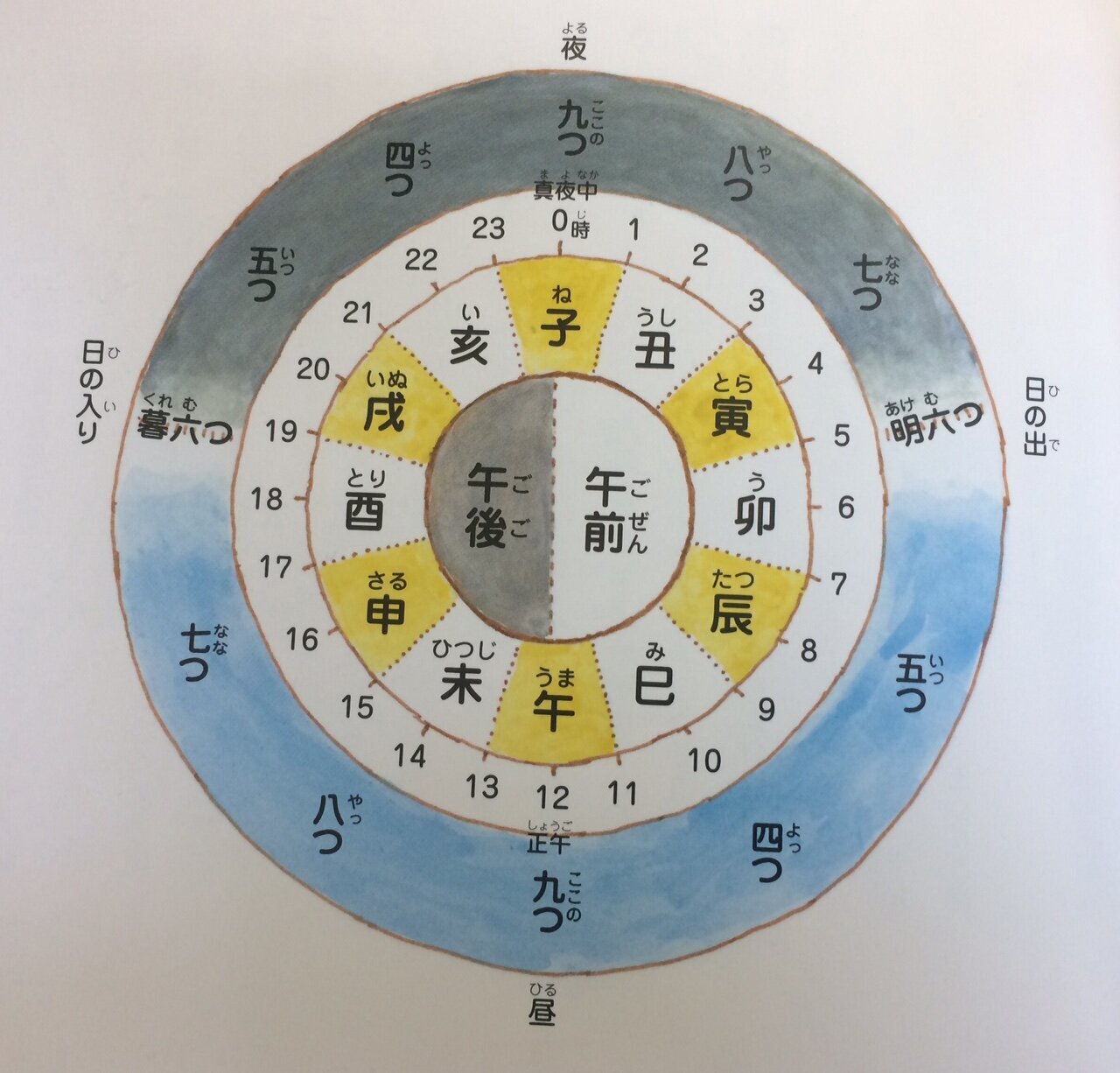

In the world of the Tokugawa, time was not a line but a garden of moving circles, where everything remained in a silent dance of light and shadow. The kanji 時 combines the sun (日) and a temple (寺), reminding us that this was not time that one “had,” but time that one “experienced” together with nature. At noon, a summer hour could last nearly 150 modern minutes, while in winter it might be barely 45. This irregular system, futei-ji (不定時), was not a primitive relic but a subtle instrument harmonized with the rhythm of nature; it allowed each moment to have its own unique flavor.

Uneven and Variable

In practice, this meant that “9:00 AM” in May and “9:00 AM” in December lasted completely different amounts of time—though no one in Edo thought of time in terms of Western minutes. The traditional Japanese “hour” was not a fixed unit, but a flexible interval—more like a stage of the day than a mathematical quantum. And since day and night were always divided into six parts, their lengths shifted smoothly with the solar day’s changes. These shifts occurred twenty-four times a year, in accordance with the points of the lunisolar calendar—such as shunbun (spring equinox), taisho (great heat), or kanro (cold dew) (more about the calendar and 72 seasonal phases can be found here: The 72 Japanese Seasons, Part 1 – Spring and Summer in the Calendar of Subtle Mindfulness and here: 72 Japanese Micro-Seasons, Part 2 – Autumn and Winter in the Calendar of Conscious Living). Only during the equinoxes did day and night—and thus daytime and nighttime hours—become equal.

The futei-ji system might seem illogical today, but in a world that knew neither electricity nor GPS nor digital calendars, it was, in fact, practical. It adapted to the natural rhythm of light and dark, allowing people to live in harmony with nature’s cycles. It was not time that one “possessed,” but time that one lived through.

Time in Characters

The most fundamental character for time is 時 (toki or ji), used for example in the word tokei (時計 – “clock,” literally “time measuring device”). The character 時 consists of two parts: on the left, the radical 日 – “sun” or “day,” and on the right, 寺 – “temple.” The second component is no coincidence: it was in Buddhist temples that time was traditionally measured, with bells rung at set intervals. In other words, the very writing of the word “time” points to its connection with the sun’s cycle and the spiritual space of the temple.

The term futei-ji (不定時), describing the variable time system in effect until the end of the Edo period, is also fascinating. It is composed of three characters: 不 (“not” or “non-”), 定 (“fixed,” “established”), and 時 (“time”). Together, they mean “non-fixed time,” “variable time”—which perfectly expresses the philosophy behind the system. In contrast, the later-introduced Western time system was called jōtei-ji (定時) – “fixed, regular time,” the kind we use to measure days today.

Time in the Japanese language was not something external, but rather something present in rituals, seasons, names, in the structure of the calendar, and even in the syntax of thought itself. It was not digital time but imagistic time—described through metaphors of light, the zodiac, incense, and the sound of bells. And that is precisely why this system, though it may appear chaotic to the modern eye, was so deeply coherent with the culture of premodern Japan.

How Did Futei-ji Actually Work?

From the dawn of Japanese statehood, time was measured in relation to sunrise and sunset. However, the precise twelve-division scheme of variable hours began to spread in the 7th century alongside the lunisolar calendar. Under the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns, the system rose to become a pillar of daily life. It was called futei-ji – “non-fixed time” – and was regarded as a natural expression of harmony with the world, as innate as the solar and lunar cycles it helped to organize.

The Day’s Skeleton: 12 Segments Instead of 24

The Day’s Skeleton: 12 Segments Instead of 24

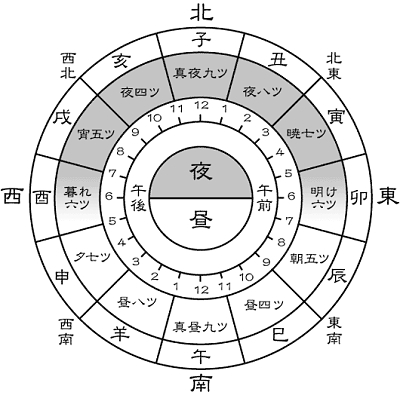

Futei-ji divided the day into twelve segments, six for daylight and six for night. Each of these was called koku (刻) or simply toki (時), but they had no fixed length—they expanded with the dawns of summer and contracted in the darkness of winter. From an astronomical standpoint, the system was elegantly simple: the first daytime koku began precisely at daybreak, the last ended with sunset; then the nighttime koku began, continuing until the next dawn. Six evenly divided portions of light and six of darkness—nothing more was needed by a farmer, merchant, or monk to synchronize fieldwork, gate-side trade, or the recitation of sutras.

Why Are the Hours Unequal?

To our modern sense of time, such an arrangement may seem troublesome, but for an agrarian society it offered only benefits. Rice ripened in the rhythm of the sun, not of the clock; the prayers of Buddhist monks echoed at dawn and dusk, so their liturgical calendar, too, had to be flexible. From the Tokugawa perspective, variable hours also served a political function: they effectively distinguished Japan from the “barbarian” West and fit into the broader ideology of sakoku—the closing of the islands to foreign dominance.

Regulation – 24 Adjustments Per Year

The key to the functioning of futei-ji was a precise chart of hour lengths prepared by court astronomers (天文方 tenmonkata). Together with poets and mathematicians, they produced calendars in which the year was divided into 24 sekki—solar “nodes” marking, for example, minor cold (shōkan), great heat (taisho), or white dew (hakuro). At each of these points, the lengths of daytime and nighttime koku were corrected by a few moments (what we would now call “minutes”): hence the frequent phrase in historical sources that “time was adjusted twenty-four times a year.” From at least the 17th century, announcements with detailed tables were distributed to all major temples and castles, from which the news spread further via the beating of drums and ringing of bells.

Engineering in Service of the Sun

Engineering in Service of the Sun

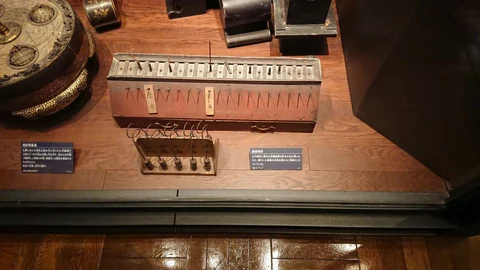

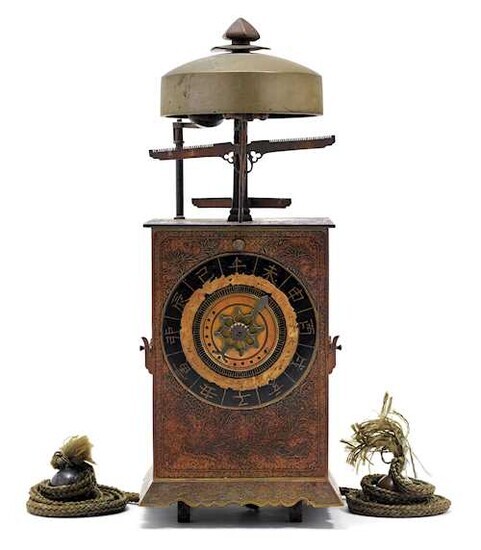

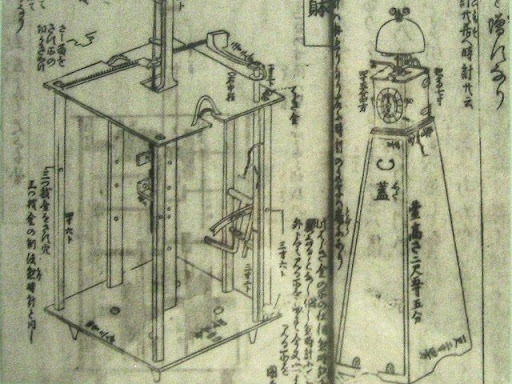

With the arrival of European clocks, Japanese craftsmen—such as Yasui Santetsu, author of the Jōkyō calendar reform of 1684—faced a conundrum: how to make metal and springs comply with non-uniform time. They solved it by inventing wadokei with dual day–night balances, adjustable dials, and zodiac signs rotating across them. The mechanism ticked at a steady pace, but the hands passed over indexes manually shifted every few days—so that their path was shortened or lengthened according to the season. Thus were created clocks that could “breathe” with the sun.

The Stewardship of Time

In Edo, the accurate measurement of futei-ji relied on an elaborate infrastructure of auditory signals. In residential districts, drums (taiko) echoed; in large squares, bells (kane) rang; and in ports, small mortar cannons fired. A watchman on duty measured the shadow on a portable gnomon or checked a water clock’s readings; if the table indicated a change in koku length, he marked it in chalk on a tablet and relayed the information to the bell tower. In this way, a kind of audible time grid was created, binding the city together before the first gas lamps had ever flickered to life.

As a result, futei-ji was not a primitive relic from before mechanization, but a subtle instrument synchronized with the rhythm of nature and the needs of society. Its irregularity allowed people to think of time not as a geometric abstraction but as something living; it made each part of the day possess its own taste, scent, and color—from the cool blue of the “Hour of the Tiger” to the glimmering gold of the “Hour of the Rooster.” Only the modernizing cut of the Meiji era transformed these pulsing koku into the 24 steel segments that now define our journey through the day.

Hours of Day in Edo

Edo-Era Clocks – From Foliots to Mechanical Marvels

Some Edo clocks had movable dials on which zodiac symbols and their corresponding numbers were shifted manually. Others featured dual mechanisms—one for day, one for night—that could be switched at dusk. Still others regulated the foliot—a horizontal bar with sliding weights—by shifting the weights daily or every few days to speed up or slow down the clock’s operation.

A separate category was the pillar clocks (柱時計, hashira-dokei)—vertical constructions where a weight descended along a guide rail, measuring “hours” according to the season. Their scales were interchangeable: one for spring, another for winter. These clocks resembled bronze-carved calendars more than our modern timepieces. Their mechanisms were sophisticated, but their appearance—with ornamental engravings, family crests, and ebony-gloss wood—made them works of functional art that adorned palaces and the grand halls of castles.

The art of Japanese horology reached its peak just before the end of the Edo period. In 1851, Tanaka Hisashige — a technical genius and future founder of the company that would eventually become Toshiba — unveiled his masterpiece: the “Ten Thousand Year Clock” (万年自鳴鐘, Mannen Jimeishō). This clock was a microcosm: six dials that simultaneously displayed Japanese and Western time, moon phases, seasons, the lunar calendar, and solar terms. At its center, a rotating globe turned in sync with celestial movements. What’s more, the clock adjusted the length of the hours automatically to match the seasons — without the need for manual adjustment.

Today, this marvel of engineering can be admired at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo. Gazing upon it, one can perhaps feel what Tanaka himself once did — that time is not a line, but a garden of moving circles, where everything remains in a constant, silent dance. In the Edo period, clocks did not merely measure time — they told its stories.

How People Measured Time in Daily Life

City Bells

This seemingly mysterious system had its own order. The number nine marked noon and midnight, when the sun was highest in the sky or when light was farthest away — the perfect center of day and night. From that point, the number of strikes decreased — eight, seven, down to four, assigned to the hours furthest from the zenith: daybreak and the darkest part of the night. Interestingly, the numbers one, two, and three did not appear in this system at all. There were several reasons for this. First, low odd numbers — especially “one” and “three” — carried connotations of impurity, emptiness, or bad omens in both Buddhist and folk traditions. Second, one or two bell strokes were too easily lost in the city’s bustle, easily confused with other signals, and thus abandoned in favor of clearer and more resonant sounds. And third — perhaps most importantly — in Japanese tradition, time was meant to be felt, not counted. Six bell strikes did not need to indicate an exact hour but rather evoke a familiar time of day, known from the bamboo’s shadow, the scent of rice soup, or the sound of sandals on stone.

When the bell struck six times at dusk — the Hour of the Rooster (酉の刻, tori no koku) — lanterns on bamboo poles lit up the narrow alleys. Three koku later, at the Hour of the Boar (亥の刻, i no koku), the city fell into silence: guards took their places at the gates, and only the night courtesans waited for clients by the glow of paper lamps.

Edo’s Time Infrastructure

In Zen monasteries, time was marked by taiko drums; in the mountain paths of Kii, echoes of the final strike carried through the sugi forests long after the sound itself had faded. In the ports, the fire brigade lit small mortars, and their thunder pierced the mist before reaching the fishermen’s boats on Edo Bay.

Incense, Candles, and Water

Incense, Candles, and Water

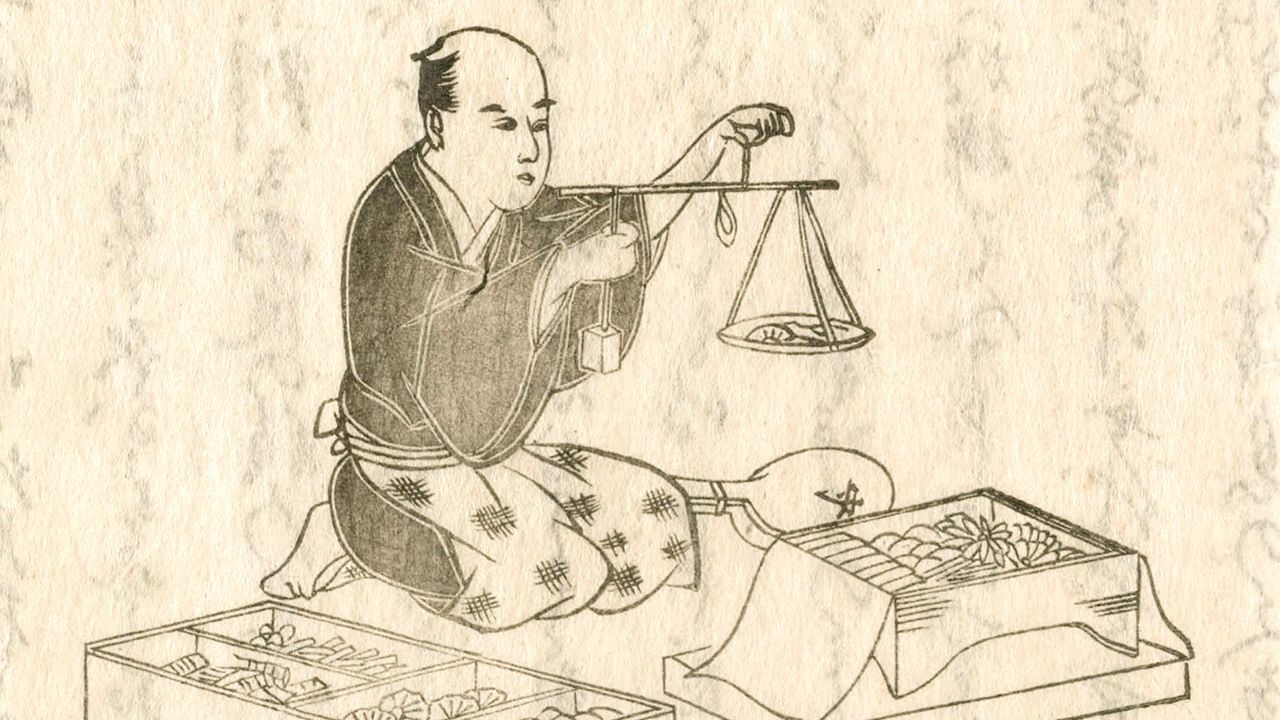

In townspeople’s homes, incense clocks (線香時計, senkō-dokei) burned quietly. One spiral of sandalwood took roughly half a koku to burn through — perfect for cooking rice or reducing soy sauce. Scholars used measuring candles with horizontal notches: as the flame reached the next groove, small metal balls would fall onto a tray, marking the next “tick” of the night. In the parlors of samurai households steeped in Confucianism, droplets from water clocks fell steadily, and a drifting cypress leaf on the surface signaled the passage of a koku.

Sandalwood Time in Yoshiwara

Thus Pulsed Time in the Japan of the Tokugawa Shoguns

Not in equal, soulless minutes, but in the warmth of sunlight and the scent of sandalwood, in the ring of bells and the rustle of silk. The clock was reality itself, and each hour — of the Tiger, Horse, or Rooster — had a color and a taste no numbered dial could ever convey.

Cats and Ninja

And when it comes to extraordinary senses of timing — ninja time deserves its own calendar. According to Shōninki, an old Japanese manual of espionage, the ideal hours for moving in the shadows were… Boar, Rat, and Tiger. In other words: late evening, deep night, and early dawn — precisely when the average guard snores and the moon trembles in a bowl of water. Everything was subordinate to strategy: during the Hour of the Rat, you slip through a fence; at Tiger, you don a monk’s disguise; and at Boar, you prepare your escape (more shinobi techniques here: Encoding the Wind – Secret Communication Techniques of Ninja Schools During the Sengoku Wars).

No wonder this all returns like a boomerang in modern Japanese pop culture. Whether in the anime Natsume Yūjinchō, where a spiritualist cat predicts weather and the moods of gods, or in the manga Neko Ramen, where lunchtime depends on a meow. Edo Japan had its clocks — and its guardians of time. And one of them, as it turns out, was an ordinary cat. Apologies — there are no ordinary cats.

Precise Mechanism and Poetry

So people began looking to the sky not only with spiritual reverence but also scientific precision. They observed stellar transits, measured local time and latitudes, and slowly — though still respectfully — the conviction emerged that time might be a mathematical abstraction, equal for all, independent of the shadow of a pine or the ringing of a temple bell.

Then came the year 1873 and, with it, an imperial edict that swept away the poetry of the old hours with a single stroke of administrative ink. Variable Japanese time — futei-ji — was abolished, and in its place came the Western, Gregorian, time-zoned, 24-hour system. The temple drums fell silent, clocks no longer tracked the sun and moon, and noon was no longer announced by a bell… but by the blast of a cannon. It was modern. And loud.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Machiya: What Were the Townhouses of Edo Like? – The Lives of Ordinary People During the Shogunate

Your Time is Your Space, Not a Frantic Race – 5 Japanese Lessons on Managing Your Own Time

Katakiuchi – A License for Samurai Clan Revenge in the Era of the Edo Shogunate

The Unidentified “Utsurobune” Object in the Time of the Shogunate – UFO, Russian Princess, or Yōkai?

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Day’s Skeleton: 12 Segments Instead of 24

The Day’s Skeleton: 12 Segments Instead of 24 Engineering in Service of the Sun

Engineering in Service of the Sun

Incense, Candles, and Water

Incense, Candles, and Water