Your Time is Your Space, Not a Frantic Race – 5 Japanese Lessons on Managing Your Own Time

Time is the Only Thing We Truly Have – and It Can Never Be Reclaimed

Time is not a resource to be exploited – it is the space in which life unfolds.

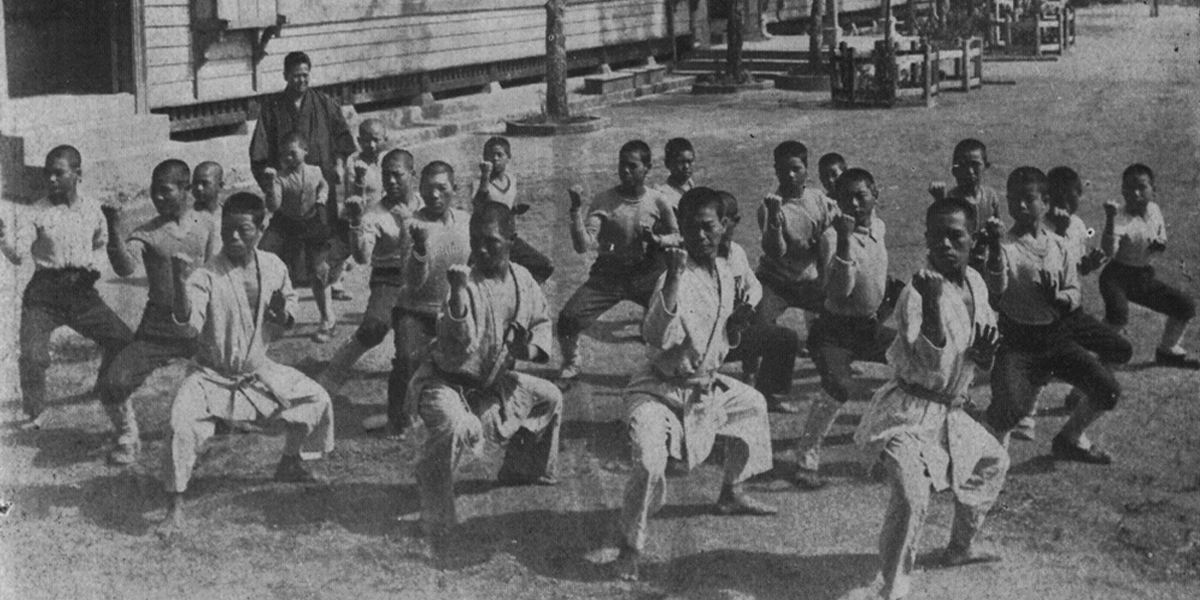

The goal is not to do more, but to do what is essential – in the right way, with peace and mindfulness. Masters of martial arts, calligraphy, and Zen did not measure their success by the number of actions they performed, but by whether each one was executed with full awareness of the moment.

How many times have we acted in haste, reacting instead of responding, throwing ourselves into a whirlwind of obligations without reflection, allowing time to slip through our fingers? We tend to believe that if we act faster, we will achieve more—that if we fill every minute, we will become more valuable. But is that really true? When life presents us with challenges, is it better to rush blindly forward, or to pause and consider which path truly makes sense? Isogaba maware—sometimes the fastest route is the long way around. Every moment is a decision—either we make it consciously, or we allow someone or something else to make it for us. Fudōshin—the immovable heart—how can we ensure that we do not react instinctively to those (whether people, brands, or corporations) who seek to manipulate our time?

It’s not about being fast. It’s about being present. It’s not about checking off tasks or letting life become a series of mechanical, random actions, but rather about shaping it like a well-composed work of art. There is no "someday," no "perfect moment"—there is only now. Time is like a calligrapher’s brush—once a stroke is made, it remains forever. The choice is ours: will we let it be an accidental mark, or will we turn it into a deliberate masterpiece?

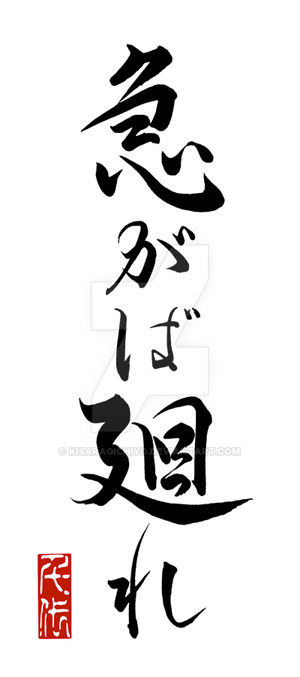

急がば回れ

(Isogaba maware)

If You Want to Reach Faster, Do Not Hurry

The Long Path: Training

Imagine a samurai warrior striving to master the art of the perfect sword cut. If he tries to achieve mastery as quickly as possible, skipping the grueling hours of training, his technique will remain flawed, and in real combat—he will fail. This is why Musashi Miyamoto, samurai, philosopher, master of the sword, and author of Gorin no Sho (The Book of Five Rings), emphasized that speed does not come from chaotic acceleration, but from fluidity and effectiveness of movement. Mindfulness in action prevents the need for corrections and, in the long run, saves time.

Paradoxically, the fastest results are achieved through dedicating countless hours to training and then unleashing that accumulated momentum in a single decisive action—whether it be a sword strike, writing an Android application, creating graphic designs, or dealing in real estate.

The Long Path: Waiting for the Right Moment

Musashi also warned against "premature movement"—acting too quickly without fully assessing the situation often led to failure. However, there is a fine line here—sometimes we mistake waiting for the right moment with procrastination, which endlessly waits for the "perfect" conditions that never come.

The Long Path: In Everyday Life

▫ Thinking: Instead of instantly reacting to stimuli and pressure, allow thoughts to mature. Many creators use the method of "setting aside" a project for a few days to look at it from a fresh perspective.

▫ Designing: Focusing on details rather than rushing leads to better results. In Japanese design, from architecture to ukiyo-e, slow, intentional composition is key. True artistry is built step by step, not in sudden bursts of inspiration.

▫ Writing: Anyone who has written anything knows that fast writing often leads to hours of revisions. Instead, it is better to write slowly and deliberately, ensuring rhythm and clarity.

▫ Decision-Making: Rushed decisions often lead to mistakes. In Japanese management strategy, the nemawashi method—gradually preparing and consulting a decision instead of acting impulsively—is valued.

In all these fields, isogaba maware reminds us: take the longer road if you wish to reach your goal faster and more effectively. It’s not about stagnation, but about conscious energy management, so that every action has meaning and value.

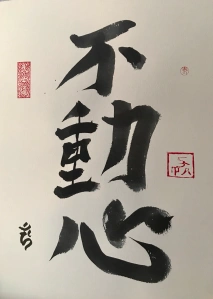

不動心

(Fudōshin)

The Immovable Heart

Samurai understood the difference between reacting and responding. Reaction is an instinct—a swift, unconscious action that once helped early humans survive. If an ancestor saw a predator, immediate escape was the key to survival. But in today’s world, reacting impulsively out of fear, emotion, or pressure often leads to poor decisions. And this is precisely what corporations, employers, brands, advertisers, and manipulators exploit. They provoke instant responses so that we act without reflection. Click, buy, agree, react, reply immediately—quick reactions benefit them, but often cost us.

“Do not react, respond.”

Reaction is mechanical and passive—it allows the situation to control us. But a person who can pause, quiet the mind, and reflect regains control. When someone attacks us verbally, should we immediately retaliate in anger? When pressured to make an instant purchase, do we truly need it? When life throws challenges our way, do we rush blindly forward, or do we stop and choose the best path?

To master time is not to dominate the clock, but to free oneself from its tyranny. In a world that demands constant urgency, there is no greater power than choosing stillness when the world demands haste.

Exercises and Practices of the Samurai

Zen Meditation (and Today’s Mindfulness)

Zen meditation allowed samurai to tame their minds and detach from the chaos of thoughts. They would sit motionless, observing their breath, letting emotions flow through them without reaction. They learned to create distance from impulses, which later translated into composure in battle. A mind trained in this way could remain internally calm even amidst conflict, if only for a few seconds—long enough to resist the natural urge for mindless reaction.

The Art of the Sword (and Modern Martial Arts)

Samurai practiced cuts and evasions in endless repetition, not to act purely on instinct, but to gain complete control over their body and mind. They did not allow emotions to dictate their movements—every action was to be a conscious decision. Martial arts teach exceptional discipline and control over one’s body and natural reflexes, turning movements into deliberate choices rather than impulsive reactions.

Breath Control (Perhaps the Most Crucial of the Three)

Breath Control (Perhaps the Most Crucial of the Three)

Mastering the breath is mastering the self. In moments of stress, breathing becomes shallow and rapid, while the mind grows restless. Samurai used techniques of deep, slow breathing to calm both body and mind. The same techniques are now employed in athletic training, pilot preparation, and meditative practices by monks. In high-pressure situations, controlling one’s breath means retaining control over one’s actions, responses, and overall mental state.

We don’t have to be warriors to apply the principle of fudōshin in our lives. Every day presents us with situations that require a choice: Do we act impulsively, or do we respond with awareness? Do we allow others to dictate our time, or do we take control of it ourselves?

In Practice:

• Facing a tempting advertisement – I can give in to impulse and buy something that suddenly seems indispensable. Or I can stop for a moment and ask myself: Do I really need this?

• In moments of stress – I can panic and act chaotically, losing control of the situation. Or I can pause, take a deep breath, calm my mind, and gain clarity on what truly needs to be done next.

• When tempted to procrastinate – I can instantly give in and choose something easier and more pleasant. Or I can take a moment to reflect on the consequences and remind myself why these tasks are important in the first place.

Fudōshin does not mean passivity—it means strength. It is the conscious decision not to be a puppet controlled by impulses and emotions, but rather their master. And in a world full of distractions, where everyone demands our attention and instant reaction, the ability to pause may be our greatest advantage.

一期一会

(Ichigo ichie)

Every Encounter in Life Happens Only Once

Our lives are composed of moments. The problem is that we rarely truly inhabit them. Our bodies are here, but our minds are elsewhere—anticipating, analyzing, checking off to-do lists, worrying about what will happen in an hour, a day, a year. Meanwhile, ichigo ichie reminds us:

"What happens now will never happen in the same way again."

We can either fully experience it, or let it pass us by.

Multitasking is an Illusion

Multitasking is an Illusion

Modern life glorifies multitasking and divided attention. We are expected to be everywhere, do everything at once, and always be "productive." But multitasking is an illusion—the more we divide our focus, the less depth and value we bring to each action. As a result, we create superficially, think superficially, and miss the details. Fortunately, science has caught up with what many have instinctively known—multitasking is a myth, proven false through countless studies over the last few decades. There is no debate anymore—multitasking is a trap.

True Creativity Requires Full Immersion

If you are fully present in your work, the final result will have depth and richness.

If your mind is elsewhere, you will create something mechanical, shallow, weaker.

Ichigo ichie teaches us that work done in full presence requires fewer revisions.

A writer fully immersed in their text doesn’t need endless rewrites.

An artist painting "with their whole being" doesn’t need to return and "fine-tune" lines.

A designer fully engaged in the process creates something well-conceived from the beginning.

Japanese Rituals of Presence

For centuries, Japan has cultivated the art of being present (mono no aware is essentially the guiding principle of all Edo-period art). Examples of this philosophy can be seen in Japanese rituals:

▫ Chanoyu (茶の湯) – The Tea Ceremony – Every gesture, from pouring water to serving a cup, is performed with full attention. When drinking tea, one does not engage in small talk or think about the future. One simply drinks the tea, exists in that particular place and time—and that is enough.

▫ Shodō (書道) – Calligraphy – A single brushstroke defines the entire work. It cannot be undone, it cannot be corrected. The essence lies in the purity of the moment of creation.

▫ Kintsugi (金継ぎ) – The Art of Repairing Ceramics – Cracks in broken pottery are highlighted with gold rather than hidden. Likewise, life’s moments—even those imperfect and flawed—are unique and valuable.

What This Means in Practice:

▫ Deep conversations and meetings – When spending time with someone important, be fully present. Don’t glance at your phone, don’t mentally plan your next task—just be there.

▫ Creating with total immersion – If you write, write with intention. If you paint, lose yourself in the colors and brushstrokes. If you work on a concept, let it fully consume you.

▫ Pausing to recognize the value of the moment – Whether in science, art, or design, solutions often come not when we desperately search for them in haste, but when we are fully present in the process.

We live in a world that demands speed, efficiency, and multitasking. But true quality, true artistry, and true creativity are born from presence, not haste.

When you sit down to work today—whether on something personal, creative, or professional—ask yourself:

Am I fully here? Am I truly creating, or just checking off another task?

Ichigo ichie is the art of treating every moment as a rare encounter—with people, with yourself, with ideas, with your work. You can embrace it, or you can miss it.

The choice is yours.

一日一時間

(Ichi nichi ichijikan)

One Day, One Hour

Time Is the Currency of Mastery

Self-improvement, learning a new skill, or nurturing creativity do not require heroic sacrifices or sudden, extreme efforts. One focused, intentional hour each day is enough. This approach aligns with the deep traditions of Japanese philosophy, where repetition and discipline are not constraints but pathways to mastery.

The Concept of Small, Conscious Steps

➤ After 1,000 repetitions, you notice your mistakes.

➤ After 10,000 repetitions, you achieve correctness.

➤ After 100,000 repetitions, movements become natural.

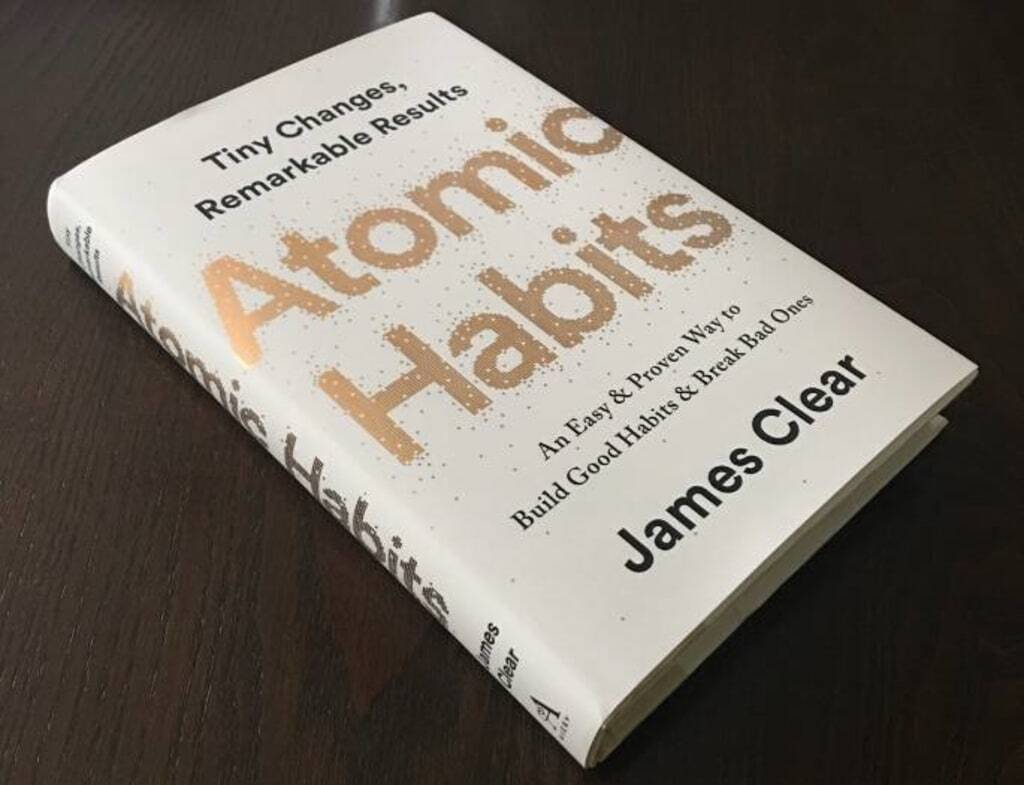

Psychological studies on habit formation (such as James Clear’s Atomic Habits or Anders Ericsson’s Deliberate Practice theory) confirm this approach. It’s not grand efforts that change lives, but small, daily rituals that gradually lead to mastery.

Japanese traditions emphasize consistency above all. In calligraphy, craftsmanship, and martial arts, there is no room for random bursts of intensity. The focus is on steady, gradual development. What today seems like microscopic progress can, in a few years, evolve into unparalleled mastery. This is the principle of compound interest—the most powerful force in the universe, according to Einstein (probably).

Application in Daily Work and Creativity

One hour a day for a year is 365 hours—nearly ten full weeks of work.

That is more than enough to transform yourself into someone entirely different.

▫ For an artist – One hour of sketching daily leads to noticeable improvements within a month, and after a year, a completely new artistic level.

▫ For a writer – An hour of writing each day means a finished book in a year, rather than endlessly postponing it for "someday."

▫ For a programmer – 365 hours of coding is enough to master a new programming language at a level suitable for professional work.

▫ For an athlete – One hour of conscious training daily is more effective than several random, intense sessions per week (although this may depend on the sport).

Every great master is simply someone who kept doing their work daily, without excuses, even when their motivation faded.

Because motivation is powerful, but temporary—it ignites like a flame, burning intensely, but quickly fading. What remains on the battlefield is something else—discipline. Discipline is what distinguishes those who reach mastery from those who never begin.

Time Is Not the Problem—Its Misuse Is

People often say, "I don’t have time." But we all have the same 168 hours in a week.

The real question is:

Do we truly lack time, or do we not know where it disappears?

One focused hour a day is enough to transform your life and achieve mastery—if that hour is used wisely, with concentration and discipline.

The idea of ichi nichi ichijikan is not about grand resolutions or radical changes. It is about building mastery through small, intentional steps.

Anyone who wants to achieve something—in art, science, sports, creativity—should ask themselves one question each day:

"Did I take at least one step toward my goal today?"

Because if you take a step every day, you will eventually arrive where others never will.

無心の心

Mushin no Shin

A Mind Free from Obstacles

The State of Flow in Japanese Philosophy

This is precisely mushin—complete dedication to action without mental distractions.

Mushin no shin is a state in which action becomes natural, almost automatic, but not mechanical. Samurai warriors described it as a state where the sword moves “by itself”, without conscious effort. Zen monks saw it as the highest form of harmony—a moment when a person ceases to be separate from their actions.

How Letting Go of Expectations Leads to Better Time Management and Efficiency

How Letting Go of Expectations Leads to Better Time Management and Efficiency

Many people approach time management obsessively—minute-by-minute planning, constant progress checking, and frustration when things don’t go as planned. But life never unfolds according to expectations. The more we try to control it, the more time we waste on stress, corrections, unnecessary revisions, and internal resistance.

The philosophy of mushin no shin teaches the opposite: act instead of overanalyzing. Focus on the process, not the outcome. Expectations are an unnecessary burden.

Fewer Expectations = Less Resistance, More Action

Many people delay new projects because they fear the result won’t be perfect.

- “I won’t start writing this book yet because I don’t have the perfect idea.”

- “I won’t learn a new skill because I’ll never be the best at it.”

But martial arts masters, calligraphers, and Zen practitioners understand that action precedes mastery. No one becomes an expert by waiting for the perfect moment. Mushin teaches that the key is to allow yourself to act without inner blockages.

Better Use of Time – Less Thinking, More Doing

- If you’re writing—write, don’t overthink the first sentence.

- If you’re designing—start sketching, don’t dwell on whether it’s already a masterpiece.

Psychologist Timothy Pychyl has shown that procrastination is not caused by laziness but by emotions tied to a task. If we perceive a task as too difficult, stressful, or unsatisfying, we delay it. Mushin is the antidote because it eliminates emotional blockages and allows us to focus purely on action.

Detachment from the Outcome = Less Frustration, More Effectiveness

Perfectionist expectations are one of the biggest traps in time management.

If you expect your first draft to be brilliant, you won’t allow yourself the natural process of learning and refining.

In practice:

Focus on action, not on thinking about action:

- Instead of planning the perfect work routine, just start.

- Don’t worry about how perfect your work will be—create.

Let go of pressure regarding results:

- Instead of assuming you’ll write a masterpiece, just write.

- Instead of stressing about failure, treat it as part of the process (and failure as a natural part of training).

Don’t revise endlessly:

- Sometimes, it’s better to complete something well and move forward than to waste time on endless corrections.

- Japanese calligraphers say: “The brush moves forward, it never goes back” (筆は後戻りしない, Fude wa atomodori shinai).

Find your rhythm—don’t fight time:

- If you’re entering a flow state, don’t interrupt it with analysis.

- If you feel that you’re working naturally, don’t ask yourself, “Am I doing this right?”—just do it.

Mushin no Shin – Effortless Productivity

It’s not about not planning. It’s not about acting mindlessly.

Mushin no shin is a state of lightness in work that appears when we allow ourselves to act without excessive analysis, judgment, and control.

By doing so, we save time, energy, and emotional strain that would otherwise be consumed by doubts, frustration, and unnecessary corrections. Japanese philosophy teaches:

- Don’t fear action.

- Don’t expect perfection.

- Simply be present in what you are doing—the rest will follow.

Mastery of Time

The goal is not to be busy, but to be present.

It’s not about doing more, but about doing what matters—in the right way.

Japanese masters—whether in martial arts, calligraphy, or craftsmanship—never aimed for speed or multitasking. Quite the opposite: their strength lay in awareness and harmony.

- A samurai who let emotions take control would lose his life.

- A calligrapher who tried to correct an already written stroke would ruin the entire piece.

- A craftsman who rushed to finish his work faster might destroy something that could have lasted for generations.

Japanese time philosophy is not about racing against the clock but finding a natural and balanced rhythm.

- Ichi nichi ichijikan reminds us: Dedicate one hour a day to growth, and you will achieve mastery.

- Isogaba maware warns: Don’t rush if you want to get there faster.

- Ichigo ichie reminds us: Every moment is unique—treat it with respect.

- Fudōshin teaches: Stay calm in chaos; don’t let the world control your mind.

- And mushin no shin grants freedom—act naturally, without unnecessary blockages and expectations.

It’s not about productivity for productivity’s sake. It’s not about checking off tasks.

It’s about living and working in a way that is full, conscious, and calm—so that every hour has meaning.

Time is like the brush of a calligrapher—once a stroke is made, it remains forever.

The choice is ours: will we let time leave random marks, or will we turn it into a masterpiece?

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life

The Most Important Lesson from Musashi: "In all things have no preferences" (Dokkōdō)

Winter Whispering Dreams: 10 Names for Snow in the Japanese Language

Red Tears and Black Blood: The Modern Haiku of Ban’ya Natsuishi

Ikebana: The Japanese Art of Speaking in Flowers

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Breath Control (Perhaps the Most Crucial of the Three)

Breath Control (Perhaps the Most Crucial of the Three) Multitasking is an Illusion

Multitasking is an Illusion

How Letting Go of Expectations Leads to Better Time Management and Efficiency

How Letting Go of Expectations Leads to Better Time Management and Efficiency