Karakuri Ningyō of Ancient Japan – Wooden Mechanical Robots That Served Tea, Danced, and Wrote

Precursors of Toyota and Hitachi

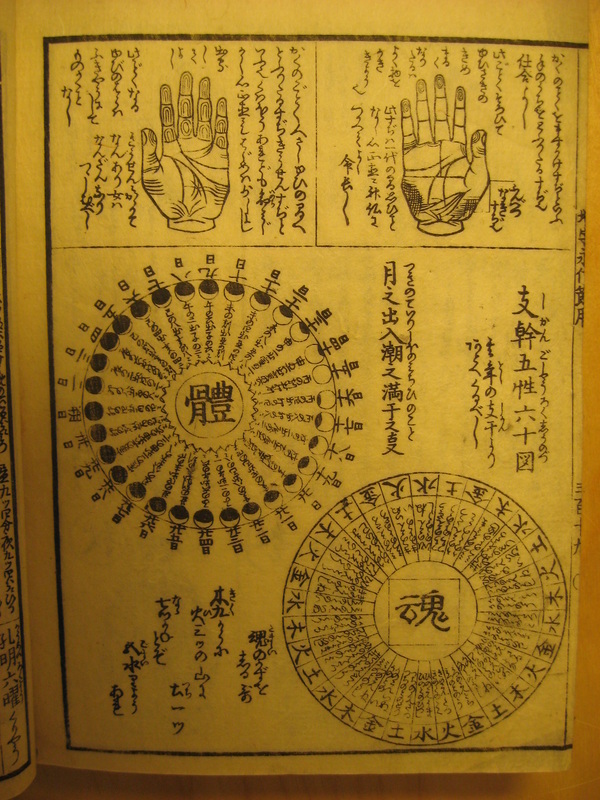

These "living machines" were not only masterpieces of craftsmanship but also objects of awe, blending art, science, and what seemed to be magic. In 1796, Hosokawa Hanzō, known as "Karakuri Hanzō," published Karakuri Zui—Japan’s first robotics manual—opening the door to the development of precise mechanisms. Moreover, the art of Japanese mechanical dolls directly inspired Sakichi Toyoda, the pioneering figure of the automotive industry and the founder of the world-famous Toyota.

The Term "Karakuri Ningyō"

Kanji

Earliest Mentions

Earliest Mentions

The etymological roots of the term stretch back to the Heian period (794–1185), or perhaps even earlier, to the Nara period (710–794). The first traces of the verb karakuru can be found in Japan’s oldest dictionaries, such as the Myōgoki from 1268, which includes definitions related to movement and thread manipulation, and the Setsuyōshū from the Muromachi period (1336–1573), which describes more practical applications of movement in craftsmanship and mechanisms.

The noun karakuri as meaning "mechanical device" only emerged during the Edo period (1603–1868), when it came to describe not only intricate clock mechanisms but also moving dolls—karakuri ningyō.

The Edo Period

In the context of karakuri ningyō, karakuri not only referred to motion and mechanics but also to the element of "magic"—the extraordinary and mysterious, as the mechanisms were hidden from the audience's view.

Today, the term karakuri remains an important symbol of Japanese engineering and craftsmanship traditions, serving as a foundation for modern technologies ranging from robotics to automated manufacturing processes.

Types of Karakuri Ningyō

Karakuri ningyō were extraordinary works of craftsmanship and engineering that took various forms during the Edo period, depending on their purpose. From intimate performances in samurai households to spectacular street shows, these wooden marvels amazed audiences. They can be divided into three main types: domestic automata, theatrical puppets, and festive dolls on platforms.

Zashiki Karakuri – The Magic of Salon Entertainment

Meanwhile, the dangaeri ningyō, or "stair-descending doll," demonstrated mastery over balance and weight distribution. By shifting internal weights, the doll could perform spectacular flips while gracefully descending stairs. In the homes of affluent merchants, shinatama ningyō—magical dolls that lifted and lowered boxes to reveal new surprises each time—were equally popular, making them perfect for social gatherings.

Butai Karakuri – The Theater of Mechanical Perfection

Dashi Karakuri – Festival Spectacles

The oldest festival of this kind, the Nagoya Toshogu Festival, began in 1619 and became a model for others. At its peak during the Tempo era (1830–1844) of the Edo period, the parade featured nine dashi floats, each equipped with karakuri ningyō. Residents worked all year to prepare the mechanisms and costumes for the dolls, whose performance mesmerized crowds and brought glory to their communities.

Karakuri ningyō were living proof that mechanics could be beautiful and art could be precise. Their variety and craftsmanship left audiences in awe while inspiring inventors, such as Sakichi Toyoda, to develop the technologies of the future.

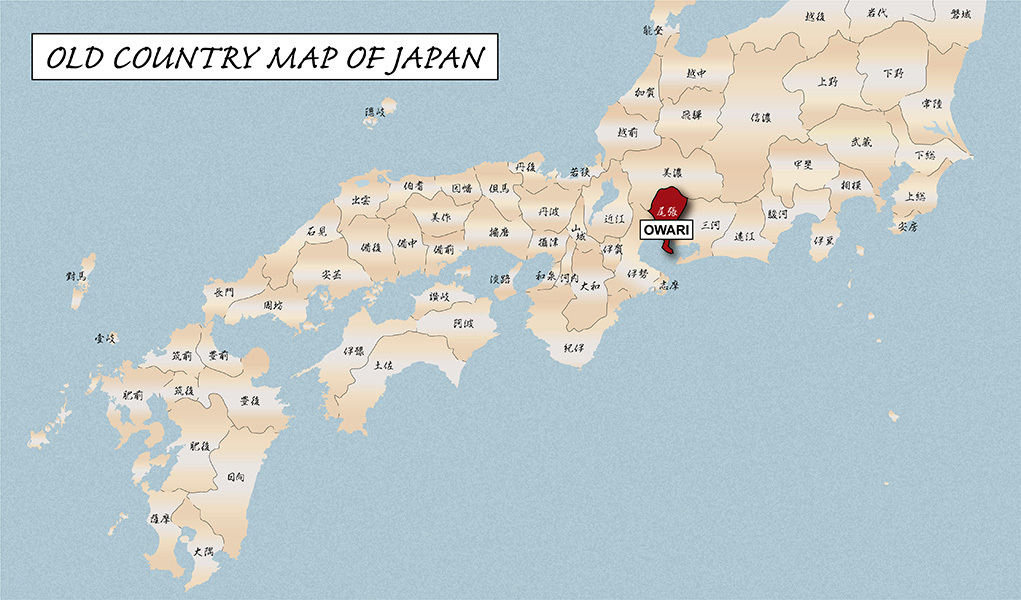

The History of the Tamaya Shobei Lineage: Geniuses of Karakuri

The story of Tamaya Shobei starts in 1734 when the first master of the family, a skilled artisan from Kyoto, moved to Nagoya at the invitation of Owari domain’s daimyō, Tokugawa Muneharu. Known for his love of luxury and entertainment, Muneharu was the perfect patron for an artist like Tamaya. In Nagoya, which was a center of clockmaking and mechanics in Japan at the time, Tamaya created his first dashi karakuri—mechanical dolls mounted on multi-tiered festival platforms. These mechanical marvels moved, performing scenes from mythology and classic stories, powered by hidden gears and springs. Spectators were left with the impression they were witnessing something magical.

However, their true masterpieces were the theatrical dolls created by the Tamaya family. One performance, still fascinating today, is Norizome Hairyono Koma—a spectacle in which a doll rode a horse, dismounted, climbed a bell, and ran around. Imagine the precision required for every movement to be smooth and natural while keeping the mechanism entirely hidden from the audience. The Tamaya theater was a phenomenon that inspired other forms of art, such as kabuki and bunraku, and drew spectators from across Japan.

Despite their success, the Tamaya lineage faced challenges. During the Meiji period, when Japan opened up to the West, traditional crafts like karakuri began to lose popularity. However, the Tamaya family survived by restoring older dolls and festival platforms. Tamaya Shobei V, fascinated by Western technologies, began documenting family techniques, preserving this knowledge for future generations.

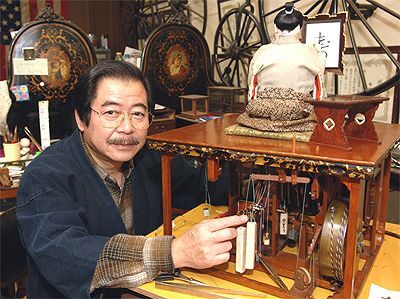

One of his most spectacular creations is a modern interpretation of the "archer" doll. He designed it based on a drawing by Professor Shunji Yamanaka, an expert in biomimetics. The doll can draw a bow and shoot an arrow, and its movements are so fluid that it’s hard to believe it is driven by a hidden mechanism and not a living being.

From Karakuri Ningyō to Toyota's Assembly Line

A Fascination with Mechanical Dolls

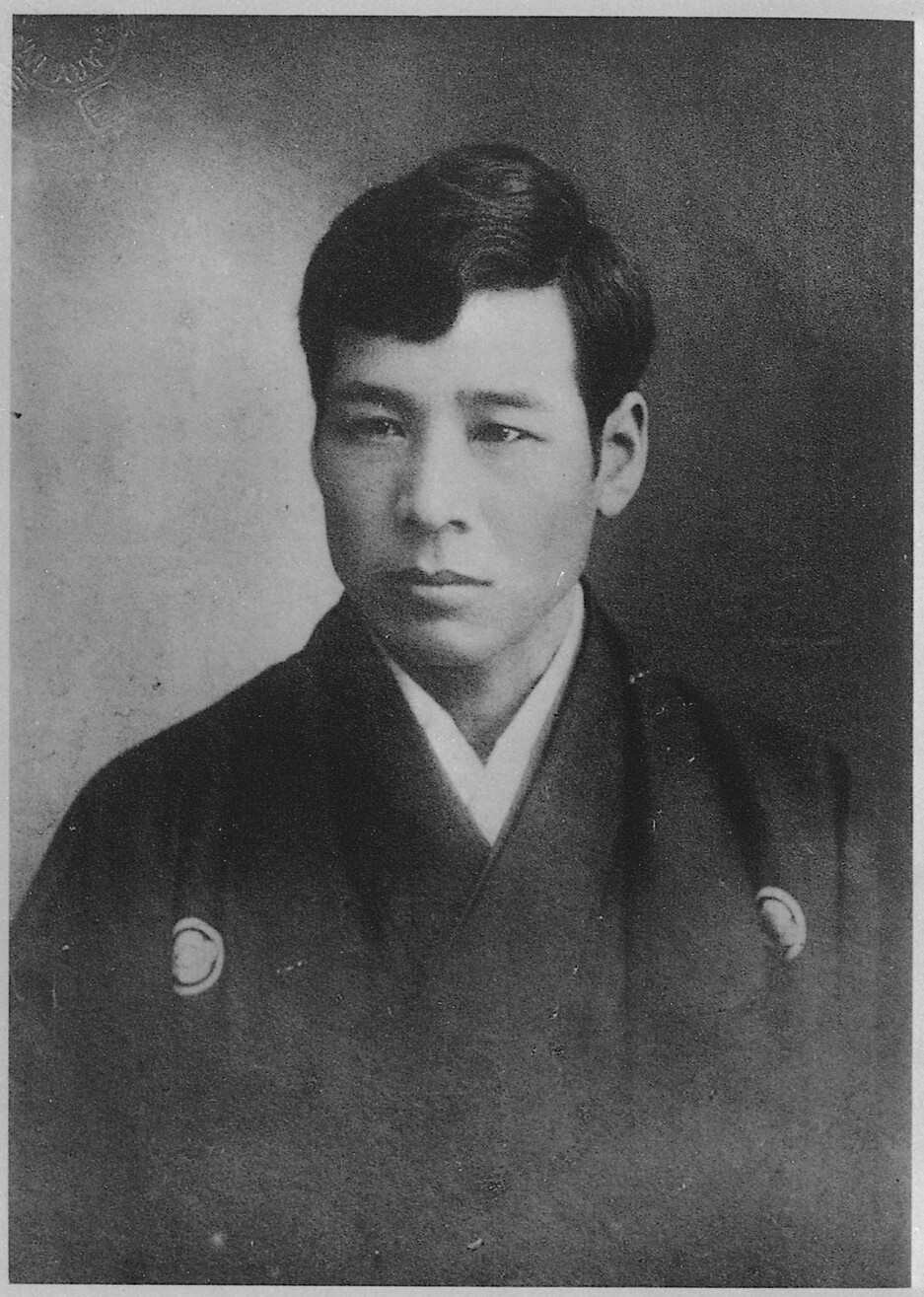

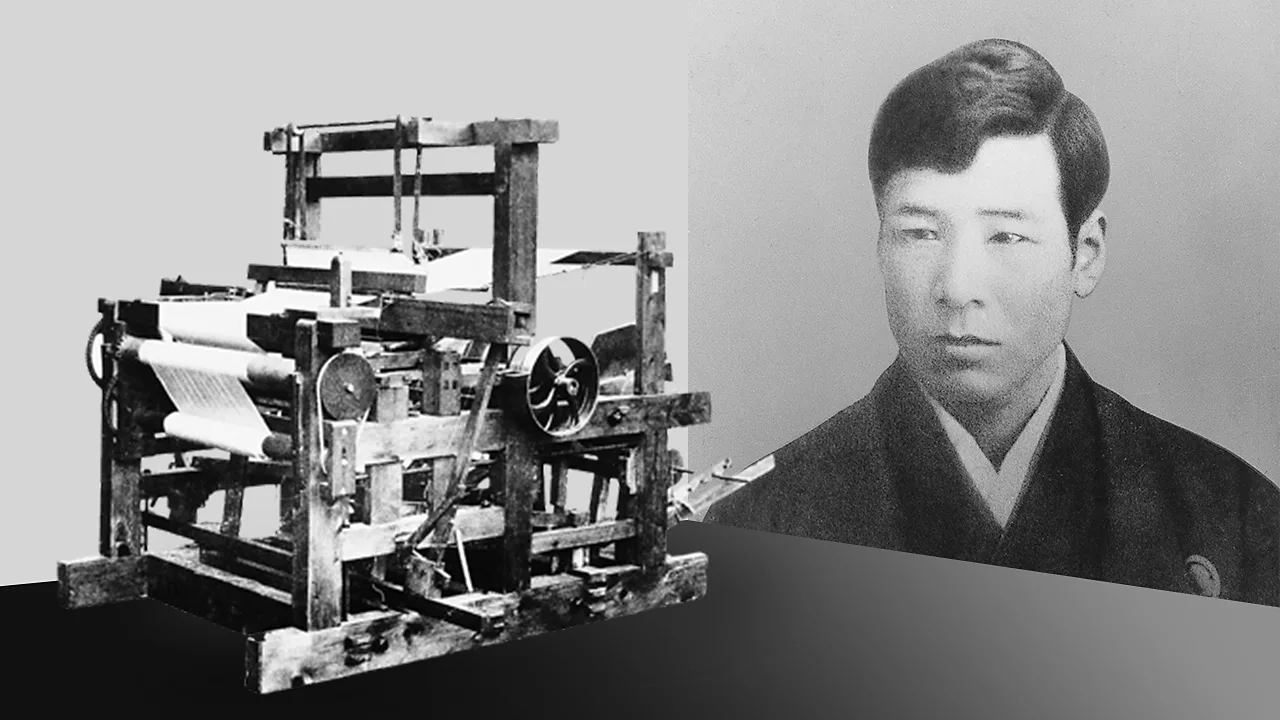

In the late 19th century, in the Owari region (modern-day Aichi Prefecture), the same area where the art of crafting karakuri ningyō flourished, a young inventor named Sakichi Toyoda marveled at the intricate mechanisms of the dolls featured on dashi platforms during traditional festivals. As the son of a carpenter, he had an innate understanding of wood precision and mechanics. His fascination with the karakuri dolls and their ability to perform smooth movements using simple mechanisms powered by springs and weights became his inspiration.

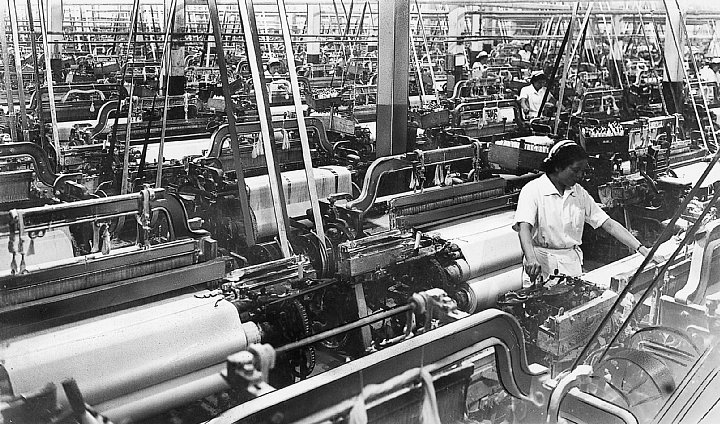

Toyoda realized that these same mechanical principles could be applied to more practical fields. At the time, Japan’s textile industry relied heavily on manual looms, requiring enormous labor. Sakichi Toyoda sought to apply mechanical innovations inspired by karakuri to create an automatic loom—a machine that revolutionized Japan’s textile industry.

A Revolution in Weaving: Toyota Automatic Loom Works

Transition to Automobiles

Transition to Automobiles

Sakichi's son, Kiichiro Toyoda, inherited his father’s passion for mechanics and spirit of innovation. In the 1930s, using the funds from the loom patent sale, he founded Toyota Motor Corporation. Although Kiichiro focused on cars, he never abandoned the philosophy that drove the development of karakuri ningyō and Toyoda’s looms—simplicity, efficiency, and precision.

Karakuri Kaizen – Modern Inspirations

Karakuri ningyō have also become an educational tool. Toyota factories host workshops where employees create mechanical models based on the principles of karakuri ningyō. This is not only a tribute to tradition but also a way to foster creativity and innovation in modern industry.

Inuyama Matsuri Festival

Since the 17th Century…

The history of Inuyama Matsuri dates back to 1635, when the local daimyō, Narusu Yoshitaka, initiated the event as part of celebrations at Haritsuna Shrine, dedicated to the region’s protective deity. While the festival began as a religious observance, it quickly evolved into a spectacle combining spirituality with entertainment. The dashi, ornate festival floats, became the centerpiece of the event, with mechanical karakuri dolls added in the 18th century, during the golden age of karakuri artistry.

In 2016, Inuyama Matsuri was inscribed on UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage as part of a group of Japanese float festivals.

Festival Highlights

One of the most thrilling moments of the festival is the nighttime display, when the floats are illuminated by hundreds of traditional lanterns, creating a magical atmosphere. The dolls, moving gracefully in the lantern light, appear almost lifelike, captivating spectators with their precision and beauty.

Exceptional Karakuri Dolls

Exceptional Karakuri Dolls

Each float features unique mechanical dolls that tell stories inspired by mythology, kabuki theater, or classical tales. Some of the most popular dolls include:

- Tengu (Mountain Spirit): A doll representing a mythical long-nosed spirit that performs intricate acrobatic movements.

Yumihiki Ningyō (The Archer): A doll that precisely lifts a bow, aims, and fires an arrow at a target, always delighting audiences with its accuracy.

- Henshin Ningyō (The Transforming Doll): A doll that changes its face or costume during the performance.

Movements such as descending stairs, spinning, or lifting objects are powered by intricate mechanisms and ropes. The entire performance is synchronized with traditional music and singing, enhancing the charm and drama of each display.

Conclusion

Karakuri ningyō continue to stand as proof of how tradition can inspire the future. They are a tribute to the artisans who not only created works of art but also laid the foundation for modern technology. As we marvel at today’s robots, it’s worth remembering that their history begins with these extraordinary, magical dolls from the Edo period.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Ninja in Retirement - What Happened to Shinobi During the Peaceful Edo Period?

The Brilliant Eccentricity of Itō Jakuchū – Discover One of the Eccentric Painters of Edo Japan

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Earliest Mentions

Earliest Mentions

Transition to Automobiles

Transition to Automobiles Exceptional Karakuri Dolls

Exceptional Karakuri Dolls Yumihiki Ningyō (The Archer): A doll that precisely lifts a bow, aims, and fires an arrow at a target, always delighting audiences with its accuracy.

Yumihiki Ningyō (The Archer): A doll that precisely lifts a bow, aims, and fires an arrow at a target, always delighting audiences with its accuracy.