Yaji and Kita on the Tōkaidō Road – Samurai-Era Japan Through the Eyes of Two City Rogues in Trouble on the Countryside

Though their legs are as weak as old sandals, the bill keeps chasing them relentlessly...

Here are Yaji and Kita—two crafty city dwellers from Edo, confident the world was theirs to conquer as they set off on a journey along the Tōkaidō Road through a land full of "provincial bumpkins." They dreamed of swindling free sake, tricking hosts out of meals and lodging, and foisting cheap cons onto unsuspecting villagers—but they invariably ended up worse off: swindled themselves, beaten, or left hungry. Yet each of their defeats was so hilarious and absurd that they evoked laughter rather than pity—and thanks to this, they became legends of Japan, fondly remembered to this day in literature, woodblock prints, kabuki theatre, manga, and anime.

Yajirōbei and Kitahachi are not armored samurai, but men in straw hats with tongues as sharp as a sashimi knife. Their conversations at times resemble a cabaret, sometimes drunken philosophy, and sometimes a convoluted exercise in the impossible. Their journey is merely a pretext—for eating local delicacies, bathing in hot springs, flirting with women (who are invariably indifferent or hostile), or brawling with other inn guests. Yet beneath this layer of humor lies something more than just a rowdy road comedy.

For Hizakurige is also a phenomenal chronicle of daily life in the Edo period: a cultural manual, a guide to dialects, a catalogue of provincial quirks as seen through the eyes of Edo townsfolk, or edokko. It is a satire on social order—with jabs at samurai, monks, the wealthy, and farmers. It is also a linguistic cocktail brimming with proverbs, puns, risqué innuendos, and classical quotations.

In this article, we will explore the adventures of Yaji and Kita through both the novel itself and the most fascinating ukiyo-e illustrations from the era—artworks that not only complement the story but become an independent, visual form of narrative. Strap on your sandals, grab a bottle of sake, and join us on the Tōkaidō Road. It’s going to be funny, strange, and delightfully edo-mae!

Yajirōbei and Kitahachi

The first is a not-so-young townsman from Edo who introduces himself as "just an ordinary old fellow" (tada no oyaji – ただのおやじ – an unremarkable old guy), though in fact he knows how to play instruments, reads Chinese poetry, and can compose official documents or cheeky verses off the top of his head.

Kita, on the other hand, is his younger companion with a somewhat more tangled past—he was once an apprentice in a shop, but after a failed courtship of the lady of the house and some misappropriated coins, he ended up homeless, taken in by Yaji.

Their friendship is a mix of teasing, solidarity, and a shared love of sake, good food, and every possible form of entertainment. They set off together on a pilgrimage to Ise, but—as you can easily guess—their spiritual journey quickly turns into a string of gags, blunders, and mad chases after women.

Take, for example, the famous scene with the witches. A downpour catches them near Nissaka, and they seek shelter under the eaves of an inn. Discovering that two mysterious women are staying there, they immediately decide to stay overnight. The so-called "witches" offer a ritual to summon spirits, and Yaji jumps at the chance—ostensibly to speak with his deceased wife.

Yet instead of solemnity, what we get is a colorful litany of grievances from the afterlife: unpaid rent, devoured fish, neglected temple offerings, and even the grim fact that the woman’s gravestone had become a public urinal for stray dogs. Thomas Satchell, in his 1906 English translation, captures the scene with a cabaret-like dynamism that highlights not only the situational humor but also the social irony: the spirit of the worn-out woman reproaches the man’s irresponsibility and recklessness—topics as relevant today as they were then.

And all of this is laced with a touch of eroticism, mistaken identities in the dark, and an unforgettable moment when Yaji, thinking he’s kissing a witch, ends up smooching the sleeping Kita.

Another time, they get into a dispute with a local shopkeeper they attempt to cheat, only to end up victims of an even greater swindle themselves.

Their journey often resembles a silent slapstick film where every entrance into an inn ends in a brawl, and every flirtation ends in catastrophe.

What makes everything even richer is the particular perspective of Yaji and Kita: they view the world through the lens of edokko—Edo townsfolk who consider themselves cultured, witty, and shrewd, unlike the "peasants" from all other regions.

This sense of superiority—often exaggerated and exposed by the author—allows Jippensha Ikku not only to amuse the reader but also to comment on social tensions between the center and the provinces, between tradition and urban cunning.

In the Edo period, when domestic travel was becoming increasingly popular, Hizakurige offered both entertainment and a satirical guidebook to Japan—filled with places, customs, foods, and dialects.

Today, Yaji and Kita are literary icons but also characters immortalized in countless ukiyo-e illustrations—always with a wry smile, amid some scuffle, or on the verge of another spectacular blunder.

What is Hizakurige?

Metaphorically, it’s a way of talking about wandering with humor, with a wink, without pomp or pretension.

It fits perfectly with the literary form in which the work was created—kokkeibon (滑稽本), or "funny books," full of gags, witty dialogues, and ironic commentary on daily life. Hizakurige was not the only such text, but it became the undisputed king of the genre—the first to merge bawdy humor with a travel guide.

Behind its success stands a man as colorful as his characters—Jippensha Ikku (十返舎一九). Born in 1765, his real name was Shigeta Sadakazu.

And why was Hizakurige created at that particular time? Because the Edo period (1603–1868) was an era of relative peace, urban development, trade, and... tourism.

Japan was closed off to the outside world, but internally it thrived—travel to sacred places such as Ise or Kyōto became not only a religious duty but also a form of recreation. People traveled on foot, in groups, often in disguise, with wooden sandals on their feet and bags full of snacks.

The Tōkaidō Road—linking Edo with Kyōto—was Japan’s main artery, teeming with life, gossip, and trade (for more on this route in ukiyo-e, read here: Yaji and Kita on the Tōkaidō Road – Samurai-Era Japan Through the Eyes of Two City Rogues in Trouble on the Countryside).

The entire novel consists of twelve volumes published between 1802 and 1822, each documenting the successive stages of Yaji and Kita’s journey. They start off in Edo, make a pilgrimage to Ise, detour to Kyōto and Ōsaka, and then continue through Shikoku and Kiso. Just when we think they have finally reached their destination, Zoku Hizakurige—the “Sequel to Hizakurige”—appears, carrying them even farther. The protagonists constantly fall into trouble, while readers—for over two decades—never tired of their chatter, blunders, and bawdy jokes.

But it’s not merely laughter for laughter’s sake. Hizakurige also served an educational function—a handy guide to the Tōkaidō Road, with descriptions of inns, local dishes, regional quirks, and characteristic figures. It is also a social chronicle of Japan: colloquial language, regional dialects, urban slang, and even erotic undertones—everything is there, just as in real life. In the background, a thread of social satire hums: mockery of hierarchy, caricatures of samurai, daimyō, monks, and merchants.

The language of Hizakurige is a colorful cocktail—a little classical poetry, a little street chatter, a little drunken babble.

And although today it is not easy to read in the original, thanks to ukiyo-e illustrations and numerous adaptations, the spirit of the story still lives—not only in literature but also in Japan’s cultural consciousness. There are also many versions adapted for the contemporary reader, which we will discuss later.

Hizakurige in ukiyo-e

Japan of the Edo period lived not by words alone—images were just as important.

And since Hizakurige won the hearts of readers, it is no surprise that it quickly found its way onto paper in the form of ukiyo-e—colorful woodblock prints that in the 19th century served the role of posters, comics, and... contemporary memes.

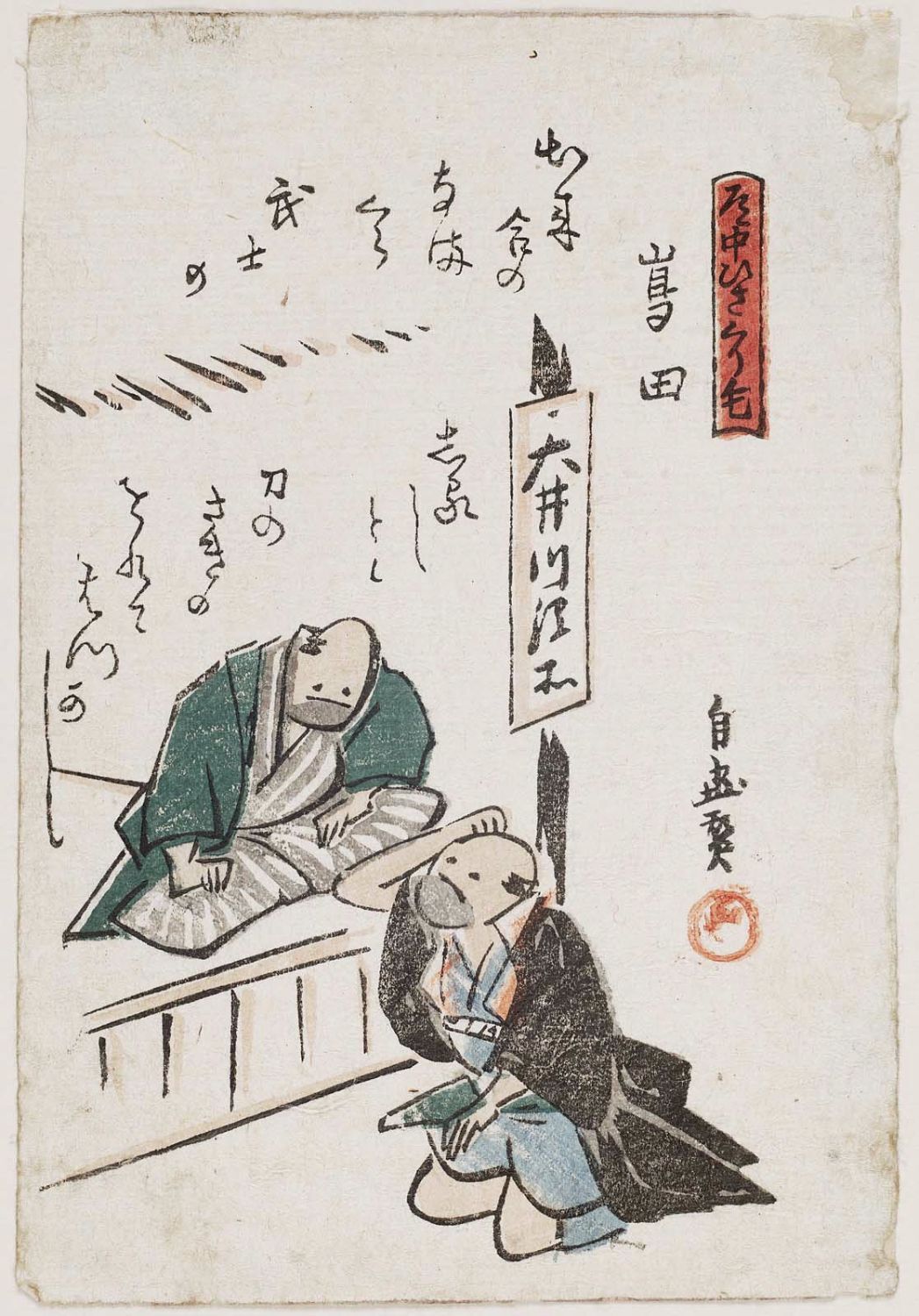

The first illustrations appeared within the volumes of the book itself, often drawn by Jippensha Ikku himself.

Over time, however, the greatest masters of ukiyo-e also turned to the novel: Utagawa Toyokuni, Utagawa Hiroshige, as well as Eisen, Kuniyoshi, and Toyohiro. Each added his own style, portraying Yaji and Kita as comic figures, instantly recognizable at a glance.

In ukiyo-e illustrations, Yaji and Kita were depicted with deliberate exaggeration.

Yaji is usually a stocky man with a face weathered by life (and sake), often slightly bowed or furrowing his brow as if not quite grasping what is going on.

Kita, by contrast, is somewhat slimmer, more combative, with a darting gaze and a readiness for action—especially where women or a bottle are involved.

In the woodblock prints, they are often shown together—one waving a fan, the other holding a straw hat, sometimes carrying their luggage.

Their figures and gestures are textbook examples of the comic duos of Edo: somewhat like a Japanese equivalent of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, but far chattier and more eager for the pleasures of life.

In the Edo period, illustrations were not mere decoration—they served an interpretive and narrative function.

The woodblock prints accompanying Hizakurige were often more than just illustrations of scenes: they commented on events, developed plotlines, added layers of meaning.

Ukiyo-e featuring Yaji and Kita are not just "scenes from the book," but independent works of art that could be admired, collected, and laughed at even without knowing the text.

Interestingly, many artists incorporated local color into their illustrations—some works depict authentic landscapes from the Tōkaidō, while others focus on facial expressions, gestures, and situational jokes.

It was a visual game with the viewer—and with reality. Thanks to this, Hizakurige became not only a literary phenomenon but also an icon of Edo’s visual culture, present on household walls, in kabuki theater, and in the collective consciousness of generations.

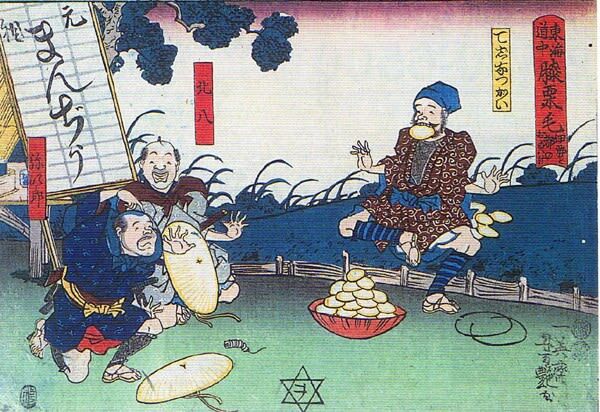

Futakawa (Frightened by a "Ghost")

二川

(Futakawa)

– Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1845–1846, Edo, series: Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui (東海道五十三対 – "Fifty-Three Pairs of the Tōkaidō Stations")

In this humor-filled and theatrically expressive scene, Hiroshige portrays two travelers—Yaji and Kita—tumbling over each other in panic, terrified by a mysterious shape floating near the road.

Their faces are distorted with fear, their poses chaotic, hurtling dynamically toward a fall.

It is, in fact, a simple kimono that frightened them—a garment fluttering on a bamboo rack, which had accidentally taken on a ghostly silhouette.

The entire composition is based on a dynamic contrast: on one hand, sudden panic and exaggerated emotionality of the characters; on the other, the banal cause of all the commotion.

It’s a scene that is not only amusing but also perfectly comments on the human tendency to succumb to imagination, especially after dark and in isolation.

This woodblock print illustrates a passage from the novel Hizakurige, in which Yaji and Kita flee, convinced they have encountered a yūrei—a Japanese ghost.

Only after a moment do they realize the apparition was merely a drying kimono.

Hiroshige captures brilliantly the transition from horror to laughter—the fleeting boundary between fear and comedy.

The illustration not only complements the literary original but reinterprets it: it emphasizes that sometimes ghosts are nothing more than wet laundry and an overactive imagination.

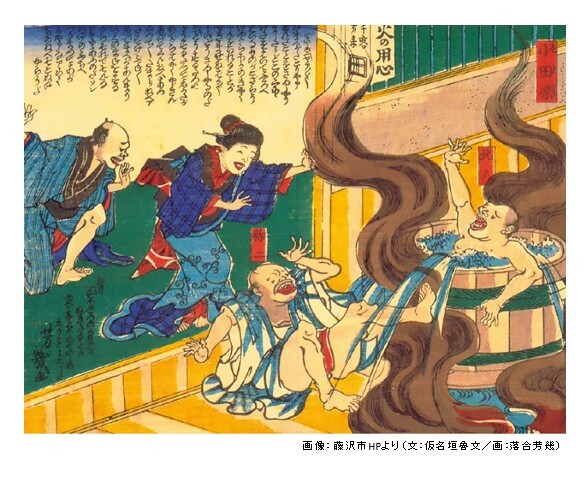

Hamamatsu – Ghost, version #2

浜松

(Hamamatsu)

– Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1845–1849, Edo, series: Hizakurige Dōchū Suzume (膝栗毛道中すゞめ – "City Sparrows on the Hizakurige Journey")

In this extremely rare and enigmatic illustration, Hiroshige depicts a moment of terror—or rather mistaken terror—experienced by Yaji and Kita, the heroes of Hizakurige.

On the veranda of an inn in Hamamatsu, during a nighttime stopover, they spot a white cloth fluttering in the wind—a kimono drying on a wooden railing. Convinced they are encountering a ghost (yūrei), they panic.

Their confused, terrified poses convey a theatrical expression typical of ukiyo-e and the comedic style of the original novel.

It is a classic example of Edo-period Japanese humor, based on fear of the supernatural and the collision between rural superstitions and everyday travel routines.

The scene from Hamamatsu is an example of a clever joke: the protagonists, known for their vivid imaginations and tendency to exaggerate, see a ghost where there is only laundry.

It is, as we see, a variation on the same theme discussed in the previous image.

Clearly, fear of the supernatural must have had a powerful hold over the people of Edo—thus, to tame that fear, irrational and comic terror often became a subject of ukiyo-e, novels, theater, and even senryū poetry (those humorous, joke-like poems formally in haiku format—more about that here: Poetry with Sake – Master Senryū and His Joyfully Malicious Insight).

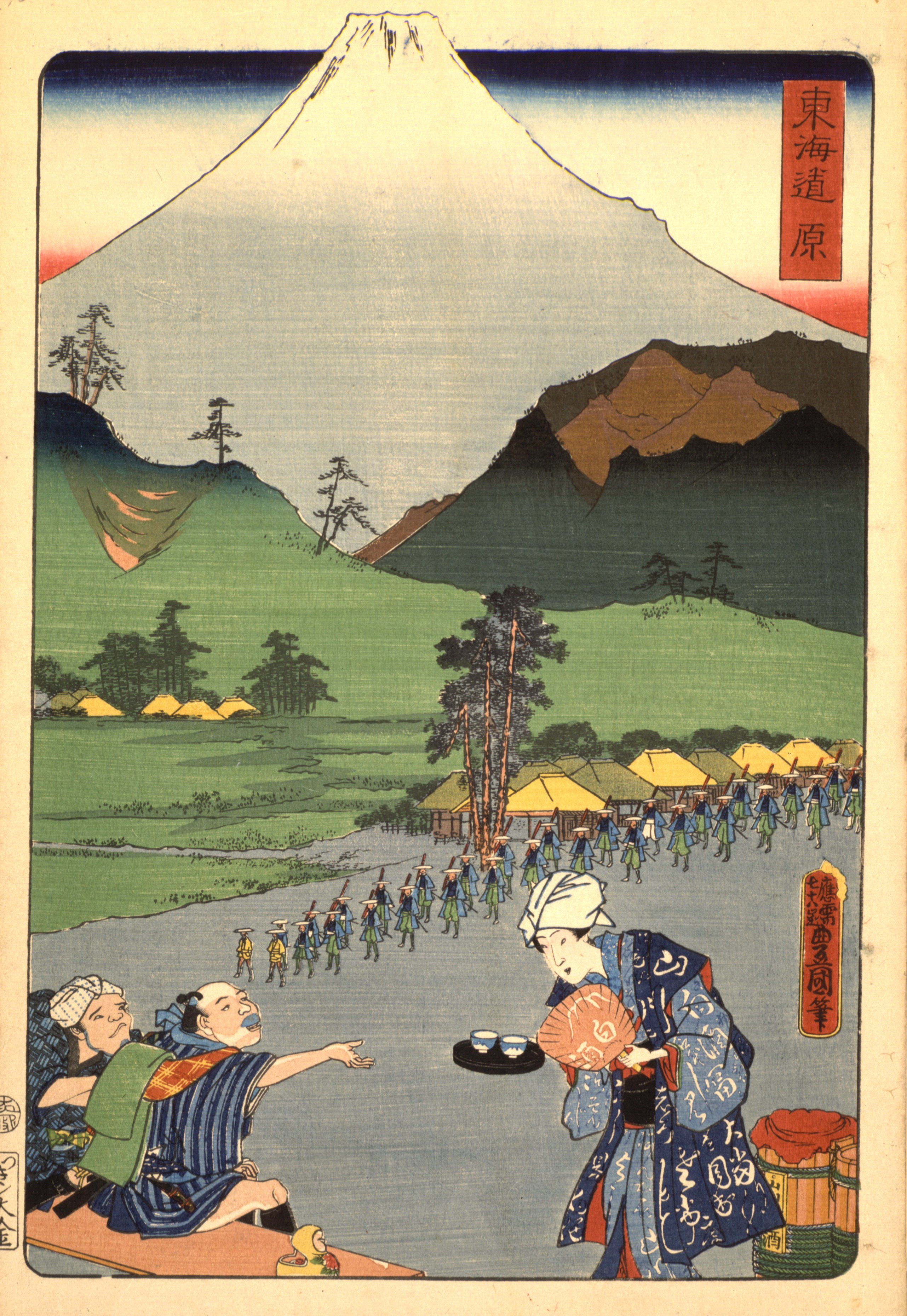

Okitsu – River Crossing

興津

(Okitsu)

– Utagawa Hiroshige and Utagawa Kuniyoshi, c. 1845–1846, Edo, series: Tōkaidō gojūsan tsui (東海道五十三対 – "Fifty-Three Pairs of the Tōkaidō Stations")

In this particularly colorful and lively scene from the Okitsu station, we witness a moment typical of Yaji and Kita’s comic misadventures.

The action unfolds by the riverbank, where porters offer to carry travelers across the water.

At the center of the image, one of the protagonists—Kita—sits comfortably in a palanquin, conversing haughtily with the crowd, while the other—Yaji—lands unceremoniously on the shoulders of a porter, wearing a thoroughly displeased expression.

The composition bursts with expressive gestures: one porter shouts, another points with his hand, everyone is in motion. In the background, other figures can be seen wading into the water, along with picturesque hills. This is a classic Hizakurige scene where the everyday realities of travel transform into farcical misunderstandings.

Ukiyo-e here serves not merely as an illustration but also as a social commentary.

The print mocks the absurdities of hierarchy and the various fees and rituals associated with travel during the Edo period.

Porters are treated with disdain, yet they literally carry the travelers’ fates on their backs.

The scene at Okitsu also captures the characteristic Hizakurige contrast between the romantic ideal of travel and the muddy, exhausting, human reality.

Hiroshige, a master of detail and movement, captured a moment that both amuses and provokes thought—not only about old Japan but also about the nature of the journey itself, stripped of idealization.

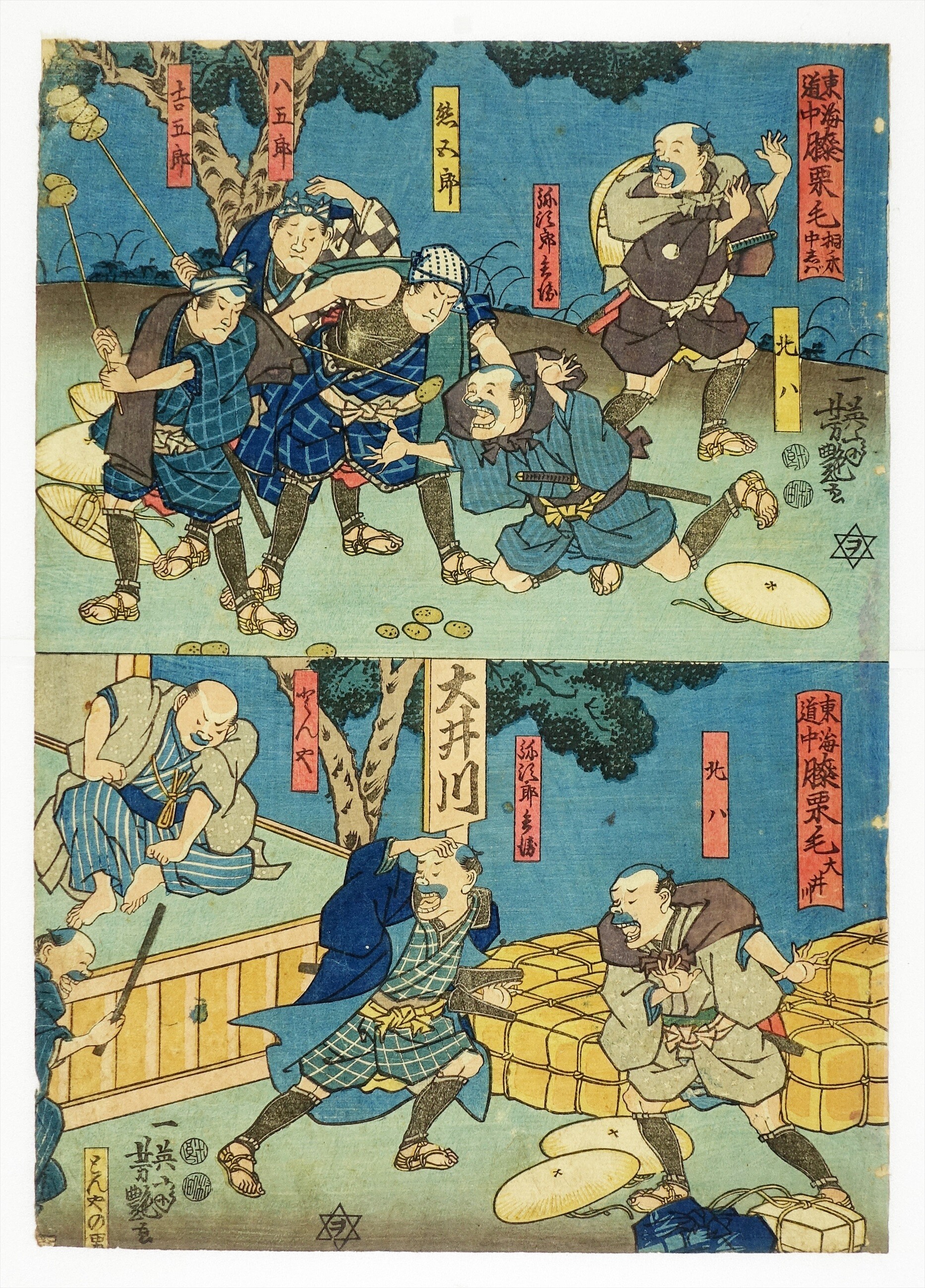

Miya – The Pilgrims' Race

宮

(Miya)

– Utagawa Hiroshige, c. 1840–1842, Edo, series: Kyōka Tōkaidō (狂歌東海道 – "Tōkaidō with Humorous Commentary")

In this dynamic composition, Hiroshige portrays a spectacular scene from a festival held at the famous Atsuta Jingū Shrine in Miya.

Two teams (one red, one blue) are shown running with a horse tethered on ropes.

These are participants of a traditional horse-racing event known as umaoi or kiba-no-gyōji, which combined elements of sport, ritual, and spectacle.

They run in rhythm, shouting as they pass beneath the imposing torii gate—a sign that they are entering sacred ground, though very human forces are at work: competition, sweat, and the joy of participation.

The image portrays Edo society not as passive participants in religion but as a community celebrating its festivals with vitality, energy, and humor. It is a scene that is both spiritual and physical—the horses, symbolic sacrificial animals, are led not by aristocrats but by half-naked, laughing workers. With masterful precision, Hiroshige captured this contrast: between the sacred and the profane, between the stillness of the torii and the clamor of the crowd.

Yaji and Kita Today

They began as pranksters in a travelogue and ended as archetypal figures of the national imagination.

Already in the 19th century, Hizakurige made its way onto the stage—both in kabuki theater and in rakugo, the art of solo comedic storytelling.

One of the better-known versions was the 1928 kabuki play by Kimura Kinka, simply titled Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige, where the parody of a meeting with a daimyō and the spiritualist scene with witches were given new, theatrical life.

In the 21st century, Yaji and Kita returned once more to the stage: in August 2016, a performance titled Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige – YJKT was staged at Kabuki-za in Tokyo, with a sequel, Kabukiza Torimono-chō, appearing the following year.

Meanwhile, the characters continued to appear in literary editions—often abridged, illustrated, translated, and adapted.

In English, the fullest translation remains Shank's Mare (also known as Footing It Along the Tokaido), translated by Thomas Satchell at the end of the 19th century—a classic that still conveys the spirit of Edo, preserving much of the original wordplay and irony.

Alongside it came contemporary adaptations for younger audiences, such as Yaji and Kita: The Comic Adventures, and even graphic novels.

Today, Yaji and Kita also feature in manga, anime, and film.

They also appear in parodic episodes in anime as archetypal "comic drifters" from the Edo period—something like the Japanese equivalent of Laurel and Hardy, on a mission to eat, drink, and escape the bill.

In 2005, the well-known film Yaji and Kita: The Midnight Pilgrims (directed by Kankurō Kudō) was released, blending travel, surrealism, music, and homoerotic subtext—proof that Yaji and Kita can survive any transformation.

Over time, they have become not just comedic characters, but symbols of the "wandering fool" of Japan—the figure who, instead of fixing the world, laughs at its absurdities, misleads trails, disrupts rituals, and always, but always, ends up with an empty bowl, a bill in hand, and a fuzzy memory of what they even wanted to achieve.

In a world full of solemnity, Yaji and Kita are the talkative, hungry, ever-moving rebels of Edo.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The True Origins of Sushi – Fast Food in the Bustling Streets of Edo under the Tokugawa Shogunate

Japanese Higher Mathematics – Wasan: The Samurai Art of Composing High-Degree Equations

Sentō Bathhouses in Shogunate-Era Japan – Dense Steam, Quiet Conversations, the Scent of Damp Pine

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!