Walking Along a Country Road in Japan, You Encounter the Ancient Dōsojin

Exploring Rural Paths

In today’s article, we will look closely at them: we will uncover the meaning of their name and kanji, trace their roots to the oldest findings, follow their evolution through the successive jidai, and then return to contemporary Japan—the one that nurtures the memory of the dōsojin during winter festivals with fire and sake, but also the one that turns them into tourist mascots and motifs in anime. For sometimes, it is not the UNESCO-listed monuments that tell the most about a country’s soul, but the small stone guardian who has remained silent at the village crossroads for hundreds of years.

What Exactly is a Dōsojin?

Appearance

Appearance

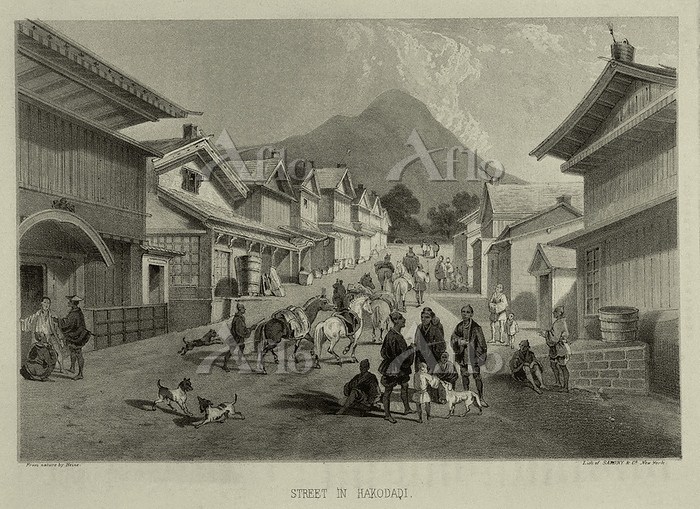

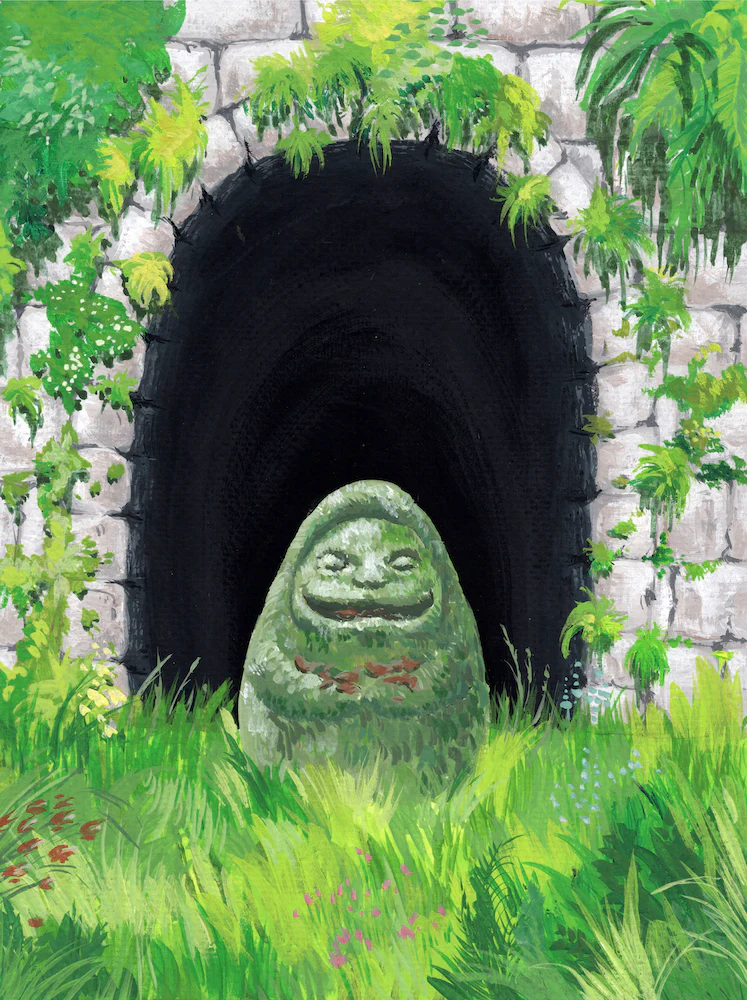

Walking along rural roads in Nagano Prefecture or straying from the main roads in the region of small Shinshū towns, one might come across something seemingly ordinary: a stone figure of an old couple standing side by side, their smiles full of tenderness. Or perhaps it was a simple roadside boulder, clearly stylized to resemble male or female genitalia (no kidding, after all, this is Japan). Or another figure—unassuming, yet exuding a kind of mysterious calm from its surface. This is a dōsojin—one of those deities that do not speak through the pathos of temple gates but whisper quietly from crossroads and shadowed bridges.

In iconography, they appear in various forms: as a somewhat fearsome yet somewhat humorous yokai, as a powerful samurai, or as anonymous stones with inscriptions.

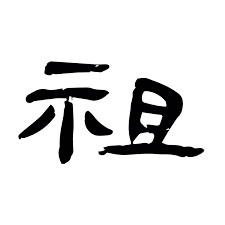

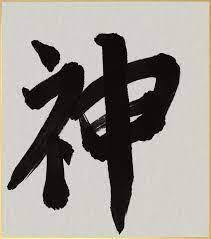

Name

But dōsojin is not the only name for this deity. In different regions of Japan, it is also called:

Dōrokujin (道陸神) – literally “god of the land road.” This name emphasizes the deity’s connection with the earth and the specific path a person travels in life.

Interestingly, some scholars point to possible connections with the Chinese road deity Kyōkōshi (共工子, Chinese: Gònggōngzǐ), whose son, according to ancient sources, was worshipped after death as a protector of travelers. Such influences may suggest syncretic roots of Japanese folk practices, which over time took on their own unique identity.

The Earliest Origins – Archaeology, Prehistory, Mythology

Traces of the Crossroads Guardian Concept Also Come from the Continent

And so, in the shadows of prehistoric forests, at the junction of myth and the first chronicles, the guardian of roads and transitions began to take shape. The stone, often phallic pillars along rural paths are the archaeological echo of the fear of chaos and the wish for fertility; the written sources transform them into boundary heroes who, on New Year’s morning, become the central figures in fiery rituals. And when you walk along a modern asphalt road in Nagano and suddenly see a pair of carved old folks nestled under a snowy roof—know that you are looking at a thousand-year-old tale of how the Japanese learned to tame the unknown with stone, fire, and a tender embrace.

Dōsojin Through the Ages

Early Middle Ages: Heian – Kamakura

Early Middle Ages: Heian – Kamakura

In the Heian period (794–1185), while the imperial court immersed itself in poetry and ceremonial life, dōsojin was not yet a commonly recognized type of deity, but its spirit began to appear in religious and folk literature. It is from this period that the first mentions originate, in which sae no kami appears as a boundary deity—a guardian of passages who wards off evil spirits and disease.

In the famous collection of Buddhist miracles Hokke Genki from the 11th century, there is a story about a village that fell into panic when a stone statue of sae no kami was damaged—an omen of an impending epidemic. This is proof that the stone figures at crossroads were no longer merely silent markers—their presence held spiritual and social weight.

Shared traits—their presence along roads, their role as guides and protectors—meant that stone figures of Jizō began to appear frequently alongside, and sometimes instead of, traditional dōsojin, especially in regions where Buddhism dominated over Shintō. Thus was born a spiritual fusion that would last for centuries.

Late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period: Muromachi and Edo

In regions such as Nagano, Gunma, Yamanashi, and Kanagawa, dozens—and eventually hundreds—of dōsojin were created—some as raw boulders, others as carefully carved elderly couples holding hands. These sōtai dōsojin (双体道祖神)—figures in pairs—were more than just folkloric curiosities. Their gestures—smiles, embraces, often kisses—were meant to bring fertility, marital harmony, and the safety of the entire community.

The Edo period also saw the development of annual fire festivals held on January 14 and 15—the so-called Ko-shōgatsu, or “Little New Year.” These celebrations—known as Dōsojin Matsuri, Dondo Yaki, or Sagichō—involved burning New Year’s decorations, paper prayers, and sometimes even specially made images of dōsojin in a great bonfire. The fire was meant to purify, drive away evil forces, and ensure good fortune in the year to come. In some villages, young men would symbolically compete for the “privilege” of lighting the fire—an act of courage, transition, and reconciliation with the deity.

Meiji and the Modern Era

In the Shinshū region, especially around Azumino, Matsumoto, and Nozawa Onsen, the cult never vanished. Today, in Azumino alone, there are over 400 stone figures of dōsojin—the most in all of Japan. Their forms are sometimes surprisingly modern: from realistic elderly figures with carved beards to stylized, almost cartoon-like characters in local cultural parks. In some places, you can even buy your own miniature dōsojin from a stonemason—as a household amulet.

What’s more, contemporary festivals are not only held, but have been recognized as important intangible cultural assets—for example, the fiery Dōsojin Matsuri in Nozawa Onsen, where each year on January 15, residents build a wooden shrine and set it ablaze in a spectacular ritual of purification, struggle, and prayers for fertility.

Diversity

The simplest and oldest form is a natural stone—often unshaped, bearing engraved characters with the deity’s name or a short prayer. These are the most commonly encountered dōsojin, found on the borders of villages or near old rice fields. Over time, 文字碑 (mojihyō) appeared—stone tablets with inscriptions. They did not depict figures, but their power lay in words: the written name of the deity, the date of creation, a plea for the protection of travelers or the health of children.

You can also find round, smooth, polished stones symbolizing the potential of life, as well as miniature pagodas with inscriptions—an echo of Buddhist gorintō, erected as a sign of spiritual protection. In northern Japan, forms connected with Batō Kannon—the bodhisattva with a horse's head, protector of travelers and their animals—are often encountered, especially along former horse routes in Aomori and Iwate.

The Nagano region, particularly the area around Azumino, is today known for having the largest number of stone dōsojin in all of Japan—many of them are couples of elderly figures, often dated to the Edo period. In Karuizawa, a popular variation features a gentle kiss on the cheek, while around Hotaka, the couple is shown pounding mochi together. Gunma draws attention with clearly phallic dōsojin, often placed at the edges of fields. In Tōhoku, especially in Yamagata, spherical dōsojin painted in reddish-brown pigment are found—perhaps as protection against the frost and malevolent winter spirits.

Festivals with Dōsojin

Dōsojin Matsuri in Nozawa Onsen

Dondo-yaki, Sagichō, Seikisū-hai

Dondo-yaki, Sagichō, Seikisū-hai

Around the same time, in hundreds of villages from Hokkaidō to Kyūshū, temporary towers of bamboo and straw are erected. They go by different names—Dondo-yaki in Kantō, Sagichō on the coast of Kanagawa, Seikisū-hai in the Chikuma valley—but the idea is the same: to burn New Year’s decorations (kadomatsu, shimekazari), talismans, and last year’s daruma dolls, to send the deity of the year (Toshigami) back to the spirit world. As the dry bamboo crackles like firecrackers, residents toss in their first calligraphy of the year (kakizome): the higher it rises on the hot air current, the more beautiful the author’s handwriting is said to become. Over the flames, rice balls are also roasted—if they split evenly, it foretells health for the next twelve months.

Though the flame may be smaller today and firefighters monitor every spark, the ideas remain unchanged: fire purifies, dōsojin watches, and a shared night beneath the cold sky unites neighbors into one warmed community.

Ancient Dōsojin on the Screen

Manga and Anime

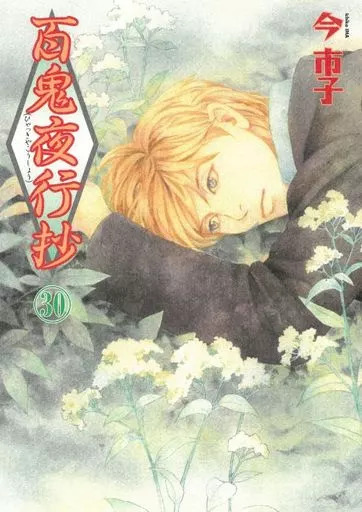

One of the most fascinating contemporary representations of dōsojin appears in the manga Hyakki Yakōshō (百鬼夜行抄) by Ichiko Ima. It is a moody tale about a boy who can see yōkai and spirits — among them, boundary deities. In one of the stories, a pair of stone dōsojin appear, watching over a valley cut off from the world — portrayed as elderly figures embracing by the roadside, meant to prevent evil forces from entering the village. Their presence not only offers protection but also symbolically marks the boundary between the spiritual and human worlds.

In Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi) by Hayao Miyazaki, dōsojin appear subtly, yet meaningfully. Early in the film, before Chihiro and her parents enter the spirit world, they pass by old, moss-covered stone statues at the forest’s edge — one of them being a pair of human-shaped figures resembling the classical depiction of dōsojin as elderly spouses. Their presence signals the crossing of a threshold between two worlds: the human and the spiritual. It is precisely at this point that the heroine’s journey begins — in harmony with the traditional role of dōsojin as guardians of transitional moments, both spatial and existential. Miyazaki does not name them directly, but the aesthetic and symbolism of these figures clearly evoke folk deities of the road and the boundary. Though unmoving and silent, the dōsojin here act as guides — guardians who watch over travelers venturing into the unknown.

The motif of dōsojin as a loving elderly couple also has a counterpart in the classical iconography of Takasago — a depiction of Jō and Uba, an aged couple raking leaves together under pine trees. This is a symbol of enduring marriage, harmony, and family happiness. This motif, originating in nō theater and classical poetry, has permeated mass culture — appearing, for example, in Natsume Yūjinchō, where older deities are fondly remembered as patrons of the home and the past.

Video Games and Aesthetic Reinterpretations

In the popular Shin Megami Tensei and Persona series (e.g., Persona 4), dōsojin do not appear under their own name, but motifs of boundary deities, guardians of thresholds, and protective spirit pairs are frequent among summoned entities (Personae). The symbolism of transition, initiation, and protection fits seamlessly into the psychological structure of these games.

Street Art, Design, Mascots

Street Art, Design, Mascots

In cities like Matsumoto and Nozawa Onsen, one can now encounter modern forms of dōsojin — not only in stone, but also made of metal, wood, and even as light installations. Some feature minimalist contemporary designs, while others resemble characters from Studio Ghibli films — with large eyes and wide smiles.

In Nagano and Gunma prefectures, some local communities have created yuru-chara mascots depicting dōsojin as an elderly couple holding hands, symbolizing travel safety and family happiness. The “Dō-chan” mascot from the village of Tsumagoi is an example of a successful blend of folklore and tourism marketing — its image appears on souvenirs, posters, and local products.

On Tokyo’s murals, especially in the Yanaka district, contemporary street art interpretations of dōsojin can also be found — often as anthropomorphic figures resembling grandparents or traveling spirits, following our steps from alleyways between old wooden houses.

Walking a countryside path

Though their form may change, the spirit of dōsojin remains the same. They are symbols of transition, but not of separation — rather, of connection between worlds: the old and the new, the sacred and the everyday, humanity and nature. The pair of dōsojin — woman and man — is an archetype of mature harmony, a shared journey through life without drama or noise, in quiet acceptance of impermanence. Perhaps that is why these humble stone deities still speak to people — not as all-powerful gods, but as warm guardians of everyday paths.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Kumano Kodo: Along the Paths of Emperors, Mystics, and Bands of Rōnin on Japan’s Camino de Santiago

Torii – The Japanese Gate of Transformation

Tōrō – The Stone Lanterns of Japan, Where Silence and the Memory of Centuries Burn

Teru Teru Bōzu – Take the Rain Away and Bring the Sun… or Snip!

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Appearance

Appearance

Early Middle Ages: Heian – Kamakura

Early Middle Ages: Heian – Kamakura

Dondo-yaki, Sagichō, Seikisū-hai

Dondo-yaki, Sagichō, Seikisū-hai Street Art, Design, Mascots

Street Art, Design, Mascots