Teru Teru Bōzu – Take the Rain Away and Bring the Sun… or Snip!

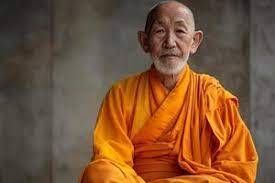

A Bald Monk, a Little Rascal, a Girl with a Broom

Its final verse goes:

“Teru teru bōzu, teru bōzu

Make tomorrow a sunny day.

But if the sky still cries—

I’ll cut off your head — snip!”

In today’s article, we will explore more deeply the custom of teru teru bōzu, those unassuming talismans that are at once handicraft, incantation, and symbol. We’ll learn what the doll’s name means, how to make it, and where it came from. We’ll also look at how modern Japan has preserved this tradition—combining folklore with pop culture, children’s wishes with an old fear of nature’s whims. And what happens if you hang the doll upside down?

What Is Teru Teru Bōzu?

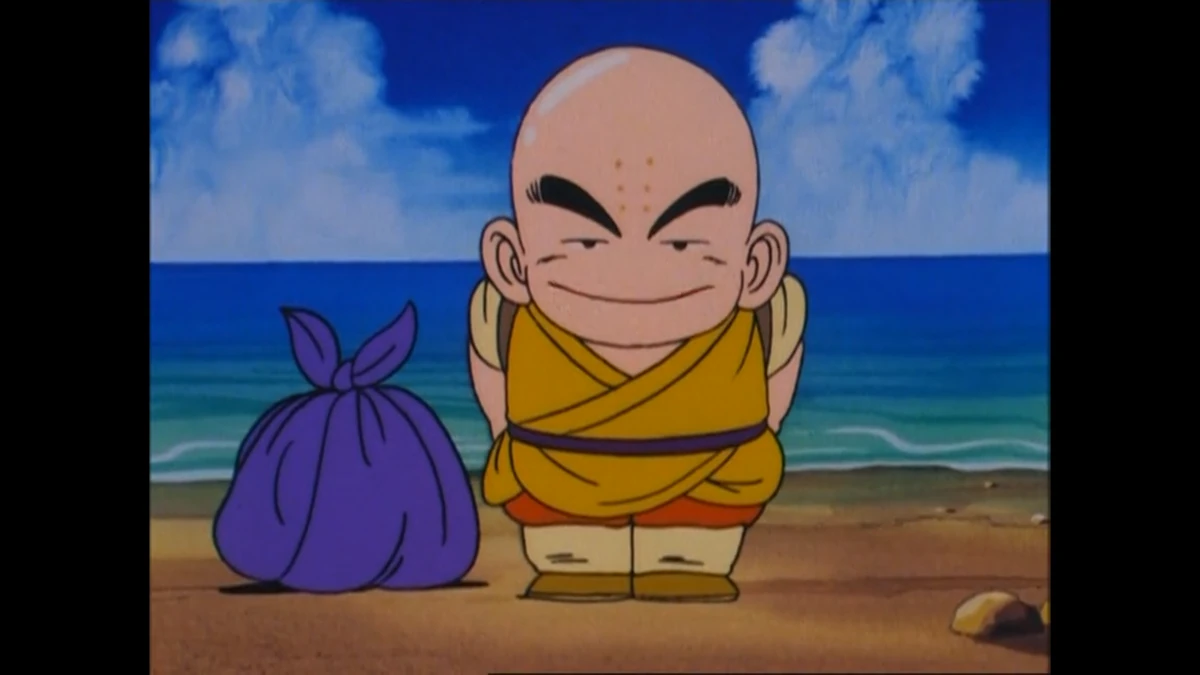

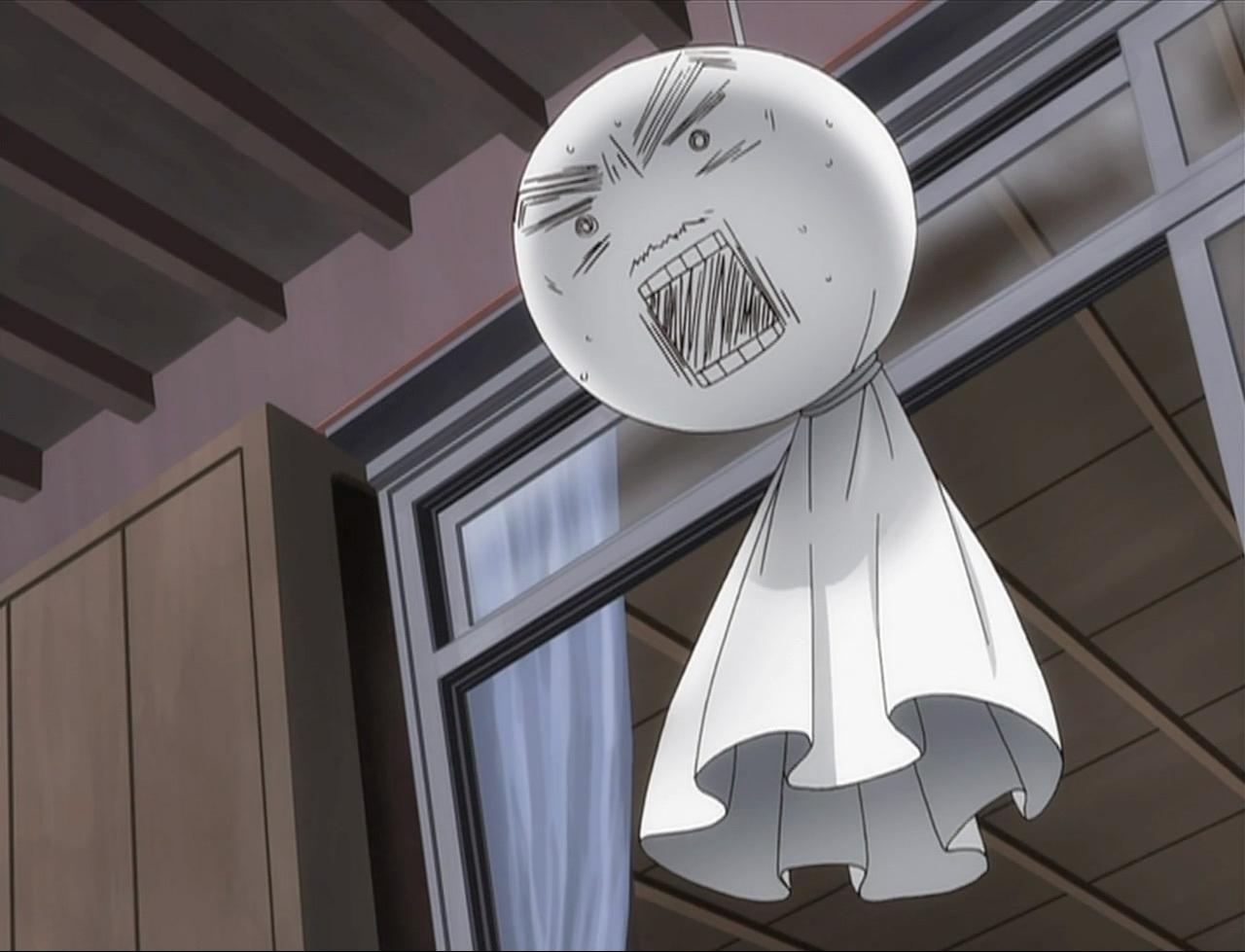

Appearance

At first glance, it looks like a small ghost from a children’s play: a round head, a white robe made of paper or cloth, a simple string tying it to the eaves or a window frame. But teru teru bōzu is not a ghost—it is a spell. A quiet whisper directed at the sky. A tiny, handmade talisman meant to stop the rain and invite the sun. Its presence against a gray sky is more than just decoration—it is an act of hope from the little ones of Japan.

These dolls appear particularly in June, when the cloudy rainy season known as tsuyu spreads across the country. At that time, dozens of white figures begin to dangle from windowsills, balconies, and the doors of children’s rooms—each one crafted with care, sometimes still without a face, as if awaiting a sign. One glance is enough: these are children asking the sky for good weather for tomorrow’s excursion, picnic, or sports day. These are preschool teachers who, together with the little ones, have made teru teru bōzu, hoping for sunshine on a day full of fun.

Though today the custom is mostly linked to the youngest members of society, it was once practiced by adults as well—especially farmers, who believed the doll could save their crops from destruction by unrelenting rain. Today, in a world of weather satellites and smartphone apps, teru teru bōzu still lives on—not as a tool to control nature, but as a quiet companion to human longing. A modest little doll that teaches us that the weather can still matter.

The Custom

Importantly, teru teru bōzu is originally faceless. The eyes and smile are only drawn the next morning, if the weather turns out fine—this is a form of gratitude for a “granted wish.” However, if the rain didn’t stop and the request wasn’t fulfilled, the doll was in danger of a sad fate—according to the old legend and the children’s song, it was to be beheaded. Today, of course, no one does this (or do they?), but the echo of this legend remains in words and gestures—sometimes the dolls are hung upside down, as a humorous way to call for rain, in case someone wishes for an outdoor lesson to be canceled. In any case, teru teru bōzu remains not only a weather talisman but also a reflection of human hopes and humor that do not pass with the weather.

The Name

The Name

The name teru teru bōzu can be read as a poetic incantation directed at the sky: “Shine, shine, little monk.” It is short, rhythmic, childlike, and at the same time possesses a surprisingly rich and ancient history. The word teru (照る) comes from the verb meaning “to shine” or “to glitter”—the same root found in the dish name teriyaki (照り焼き), where it refers to the glossy glaze on the meat. The kanji 照 contains the ideogram for fire 火 and a component referring to reflection and illumination, giving it a highly visual, almost sensory quality. It’s not light in a technical sense, but light that gleams and reflects—sunlight.

It’s worth noting that the name teru teru bōzu was not the only term used to refer to this figure. In old sources from the Edo period, variants such as teri hina (照り雛), teri hōshi (照り法師), hiyori bōzu (日和坊主), and tere tere hōshi (てれてれ法師) appear. Each of these names carries different nuances—hina suggests a link to festive dolls, hōshi is a more literary word for monk, and hiyori means fair weather, a clear day.

All these versions show that teru teru bōzu was not always merely a children’s figure. It was part of a larger folk tradition in which language, weather, spirituality, and everyday worries intertwined. It was only later—partly due to the popular children’s song from 1921—that the name we know today became dominant. But even now, when children make these white dolls in hopes of sunny weather, they say the name with the same trust that once accompanied an incantation spoken to a prophetic monk or a weather spirit.

History and Origins of the Custom

The earliest shadow of teru teru bōzu appears in China. A legend from the Tang dynasty tells of a young girl with a broom named 掃晴娘 (saoqing niang – “The Maiden Who Sweeps the Weather”). During catastrophic downpours, she was symbolically—or according to some versions, literally—sacrificed in order to “sweep” the rainclouds from the sky. In her honor, people would cut paper silhouettes of the girl with a broom and hang them under the eaves of their homes, praying for a clear blue sky.

A hundred years later, in 1921, the tradition passed into the hands of children. In the monthly magazine Shōjo no Tomo, the song “Teru Teru Bōzu” was published, written by Asahara Kyōson (lyrics) and Nakayama Shinpei (music). The melody asked for sunshine—and warned of the threat of beheading if the request was not fulfilled. Paradoxically, it was this slightly macabre warabe uta (traditional children’s song) that solidified the custom in the form we know today: a white doll, childlike imagination, and whimsical weather.

Legends

The Monk

One year, relentless rains destroyed the harvest across an entire province, and the local daimyō, desperate to save his land, summoned the monk and ordered him to pray for good weather. The monk promised that the clouds would vanish the next day and the sun would once again shine over the rice fields. But the sky remained silent. Rain poured down like the tears of gods, and the daimyō, judging the prayers to be futile and blasphemous, ordered the monk beheaded.

His severed head was wrapped in white cloth and hung under the eaves of the manor—not as punishment, but as a desperate offering to the heavens. Thus, according to one version of the story, teru teru bōzu was born—the pale paper monk of children, whose real-life predecessor paid with his life for the promise of a cloudless sky.

The Sacrifice

The Sacrifice

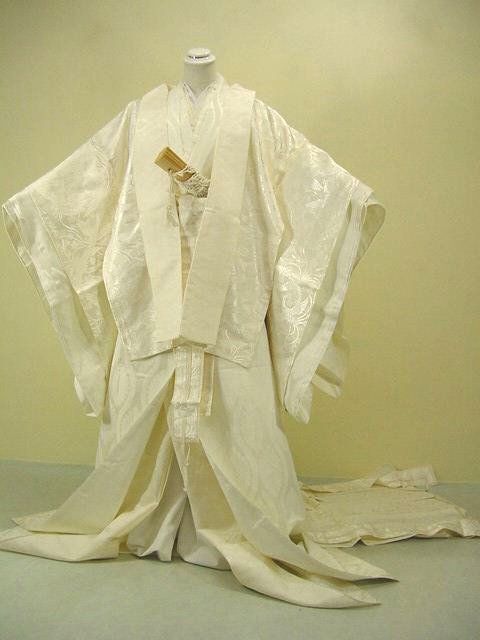

Another legend, perhaps even more poignant, reaches deep into the Heian era and brings us to a time when rain was not just a meteorological event but a divine punishment (we already touched on this in the previous section). In this story, the rain was said to be a sentence from the heavens upon a wicked or disobedient community.

When the downpours lasted for weeks, threatening to flood the city, a voice was heard from the heavens: “If you wish to save your homes, you must sacrifice the most beautiful girl, who will cleanse the sky.” A young girl dressed in a white kimono, with a broom in her hands, was led to the center of the square. There, she symbolically “ascended to heaven” to sweep away the rainclouds and restore the blue sky. After her death, the skies indeed cleared, and the grateful townspeople began cutting paper figures resembling her and hanging them under their eaves. Though time has blurred the details, her memory lived on in the teru teru bōzu doll—today a monk, once a girl with a broom.

Yōkai

Yōkai

In Japanese mythology, there is also a yōkai figure named Hiyoribō (日和坊). This weather spirit, rarely seen and little known, appears only in full sunshine—never in the rain. It is believed that Hiyoribō brings cloudless skies and gentle rays of light, and on rainy days vanishes from human sight, hiding in the mountains. His presence was always subtle—invisible but perceptible—and some say that he inspired the first teru teru bōzu, as a “substitute form” sent skyward.

The Song

But perhaps the most ominous trace of ancient beliefs is… the children’s song. “Teru teru bōzu, teru bōzu, ashita tenki ni shite okure…”—children hum, asking the doll for a sunny day. The first two verses sound like an innocent charm: if you grant the wish, you’ll receive a golden bell and plenty of sweet sake. But the third verse strikes a darker tone: “And if it doesn’t clear up, and the sky keeps crying… I’ll cut off your head, snip!” A threat directed at the little doll who failed in its task, echoing an ancient ritual. Today it’s sung with a smile, sometimes skipped entirely, but its meaning endures—a reminder that even Japanese rituals are not always light and innocent.

How to Make a Teru Teru Bōzu

You will need:

– two tissues or pieces of white fabric,

– a rubber band or a piece of thread,

– a string for hanging,

– (optional) a ping pong ball or crumpled paper to form the head.

An important and often overlooked element is… the face. Traditionally, teru teru bōzu has no facial features—at least, not until it has fulfilled its role. The absence of a face represents a state of waiting: an empty head expresses no emotion, imposes no outcome. If the weather turns out fine the next day, children draw on the eyes and smile—as a gesture of gratitude. In the past, it was believed that drawing the face too early might disappoint the weather spirit and bring rain—in fact, ink might run down the paper like tears.

Where to hang it? Ideally outside—under the roof, on the balcony, by a window frame—so the doll can “look” toward the sky. The head should be upright—drooping heads are a bad omen, weakening the power of the charm. Some people reinforce the back of the head with tape to keep the talisman from sagging under its own weight. Teru teru bōzu is best hung in the evening, the day before the planned event—in the spirit of hope that the weather will listen during the night and the morning will bring sunshine.

Small, Yet Meaningful

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Fūrin Chimes– Spirituality Can Have the Lightness of a Summer Afternoon

Kokedama – A Tiny Moss Planet That Brings the Forest into Our Concrete Homes

Rain as a State of Mind in Japanese Ukiyo-e Art

The Kanji of Happiness – How to Read the Ancient Clues in the Character 幸 ("kō")

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Name

The Name

The Sacrifice

The Sacrifice Yōkai

Yōkai