Tōrō – The Stone Lanterns of Japan, Where Silence and the Memory of Centuries Burn

A Lantern That Is Not Meant to Illuminate

The Name “tōrō”?

The word tōrō (とうろう) is most often written with the characters 灯籠, though other variants are also encountered: 燈籠, 灯篭, or even 灯楼—each of these forms carries subtle semantic and stylistic differences, and their use can be dictated by era, religious context, or aesthetic preference. The first character—灯 (tō, hi)—means “light,” “fire,” “flame.” In its traditional form, 燈, the fire component (火) is more clearly visible, combined with the character 登 (“to ascend,” “to rise”), which can be interpreted as rising light—a character of poetic construction. The second ideogram—籠 (kago, rō)—means “basket,” “container,” “cage,” something that shelters or protects what is within. As a result, tōrō literally means “basket of light” or “cage of fire”—a lamp enclosed in a protective form, not only to keep the flame from extinguishing, but to allow the light to be directed, subtle, precise.

The word tōrō itself was borrowed from the Chinese language—from the original form 燈籠 (dēnglóng)—used in China since the Han dynasty to refer to lanterns with a wide range of applications: domestic, temple, and street use. With the expansion of Buddhism through the Korean Peninsula to the Japanese archipelago in the 6th century, not only the object but also the concept arrived in Japan. However, it was in Japan that tōrō acquired new meanings, forms, and functions—gaining their own unique identity, deeply rooted in the local spiritual landscape.

Beyond the general term tōrō, Japanese language includes a whole range of related names, specifying the type, form, or place of use of a given light source:

□ Ishidōrō (石灯籠) – the most common form of stone lantern, literally “stone tōrō”; used mainly in gardens, temples, and shrines.

□ Tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠) – a hanging lantern, suspended beneath the eaves of temple and palace roofs, made of metal or wood.

□ Chōchin (提灯) – a collapsible, most often paper lantern used in streets and during festivals; lightweight, portable, often decorated with crests, calligraphy, or scenes from myths. These are often seen in narrow city alleys—by izakaya pubs or food stalls, for example.

Each of these words describes not just an object, but an entire cultural phenomenon—the way Japan gave light a structure, a shape, and a soul. And all of it begins with a simple yet incredibly rich concept: tōrō, a cage for light that does not so much dispel darkness as lead us through it.

The History of Tōrō – From Ancient Temples to Video Games

When Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 6th century, it brought not only doctrine and sutras. It also introduced aesthetics, rituals, and objects—among them lanterns, which from the outset were regarded as more than practical sources of fire. Tōrō—as they began to be called on the archipelago—were meant to illuminate not only paths, but minds.

In the Asuka period (538–710), when the Yamato court sought to “tame” the new teachings flowing from the continent, lanterns were placed in temples as offerings to the Buddha. Their light symbolized wisdom, dispersing the darkness of illusion (māra), and served as a reminder of the path to enlightenment. At that time, tōrō were massive, stone, simple—stern, like the very doctrine they represented. The oldest of them have survived to this day—in the Taima-dera temple in Katsuragi and in the Kasuga-taisha complex in Nara, which would eventually become one of the most important centers of the lantern cult.

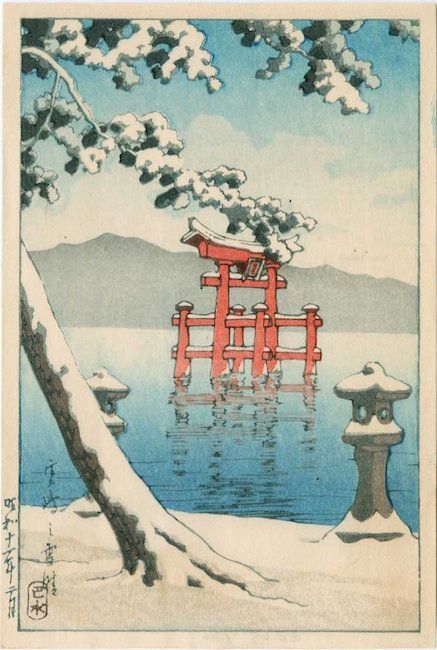

When the Heian period (794–1185) arrived, Japan slowly turned its gaze away from the continent and began to look inward. It was then that lanterns began to leave strictly Buddhist interiors and appear in Shintō shrines—the native religion, where light held a different, more primordial meaning. Here, in front of the sanctuaries of nature deities, tōrō became yorishiro—objects capable of attracting kami. They symbolized presence, the boundary between the visible and the invisible. They were also placed in the gardens of aristocrats—not as decoration, but as a sign of belonging to the world of harmony and ceremonial attentiveness.

And yet the spirit of tōrō did not fade. Today, in an age of rediscovered tradition, the lanterns are returning—to city parks, near museums, in Japanese gardens being newly created in Tokyo, Kyoto, and… Kraków (yes, indeed—yukimi-dōrō can be found even here). They have become a symbol of Japan’s eternal aesthetic—the one that speaks of simplicity, light, silence, and transience.

But tōrō did not remain only in the world of stone and shadow. Their spirit has also permeated the realm of contemporary media. Stone lanterns appear today not only in jidaigeki films or nostalgic anime about life in earlier times, but also in video games, where they serve both aesthetic and symbolic purposes. In more obvious titles like Ghost of Tsushima, tōrō illuminate the paths leading to temples and hot springs, creating an aura of spiritual immersion in the world of old Japan. In the Nioh series—filled with demons and references to Buddhist cosmology—lanterns are everywhere. In Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice or Tenchu, lanterns are silent witnesses to stealth missions, where light and shadow play a leading role. Even in more modern, stylized worlds—like in Ōkami, where we embody the wolf goddess Amaterasu—tōrō reappear as part of the divine landscape, evoking shintō and Japanese aesthetics. Not to mention the masterful Ghostwire: Tokyo. Thus, the former “cage of light,” once humbly placed in front of temple pavilions in Japan, now shines on screens in nearly every country in the world.

Now that we know where these now instantly recognizable lanterns—these symbols—have journeyed from, let us explore what meanings are encoded in their form.

How Is a Tōrō Built, and What Does It Mean?

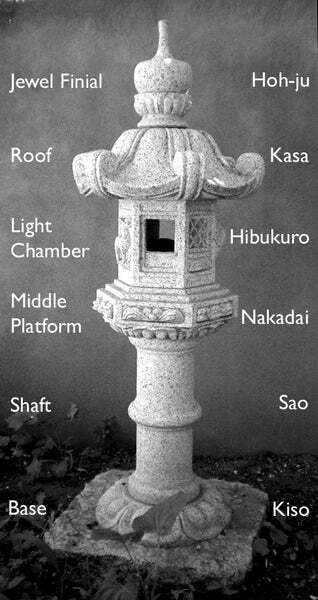

At the top is the hōju (宝珠)—a spherical finial shaped like a flame or a Buddhist jewel, symbolizing spiritual enlightenment and ultimate truth. It is not merely an ornament—it is a metaphysical crown, like in a pagoda or stupa.

Beneath it sits the roof—kasa (笠), resembling a straw hat. It protects the fire chamber from rain and snow, and simultaneously symbolizes the layer of air—fū. Its shape and proportions are closely tied to the harmony of Japanese aesthetics—too wide and it overwhelms, too narrow and it loses elegance.

The heart of the lantern is the fire chamber—hibukuro (火袋), literally “fire bag”—the place where the flame was once placed. This part represents the element ka—fire—and the spiritual light of wisdom that dispels illusion. Formerly made of pierced stone, it is often empty today, but still symbolic.

It is supported by the middle platform—chūdai (中台), serving as the connection between the sacred and earthly parts. This element has a stabilizing and aesthetic function, often adorned with simple patterns.

The shaft of the lantern—sao (竿)—is its pillar, corresponding to the element of water (sui). Sometimes slender and straight, sometimes massive and irregular, it may also be partially buried in the ground—to emphasize unity with nature.

Interestingly, although the lantern has six parts, the Buddhist symbolism of go-dai—the five elements—still dominates: earth (chi), water (sui), fire (ka), wind (fū), and void (kū). The entire structure resembles a miniature gorintō—a Buddhist funerary stupa, with which it shares both meaning and formal connections. Like a pagoda, the tōrō guides the gaze—and consciousness—from the heavy matter at its base toward the void, which is not nothingness, but a spiritual space (more on the meaning of emptiness here: The Roaring Silence of Waterfalls: Hiroshi Senju and the Art at the Edge of Understanding and here: Spiritual Landscapes in Japanese Sumi-e Art).

Over the years, as gardens became overgrown with moss and stone covered with patina, tōrō also began to embody the ideals of wabi-sabi—the beauty of transience, imperfection, and silence. Every crack, chipped corner, or lichen on the edge of the fire chamber did not diminish their charm—on the contrary, it made them more authentic. Tōrō ceased to be mere objects—they became stories etched in stone.

Types of Tōrō

Although all tōrō are united by fire and stone, their diversity can be surprising—from those suspended in the shadow of temple eaves to lanterns hidden in the mosses of tea gardens. Each form carries its own story, function, and symbolism, and their typology reads like a survey of Japan’s aesthetic and spiritual paths.

▫ Hanging – tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠)

▫ Hanging – tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠)

This is the oldest form of tōrō, with a delicate structure made of bronze, copper, or wood. Suspended beneath the eaves of Buddhist temples and Shintō shrines, they often accompanied rituals and festivals. Their metallic, chiming sound in the wind was believed to ward off evil spirits and at the same time invite the kami. You can see them, for example, at Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara—dozens of such lanterns forming a luminous path toward the sacred.

▫ Standing – dai-dōrō (台灯籠)

▫ Standing – dai-dōrō (台灯籠)

This is the most recognizable form of tōrō, placed in gardens, along pathways, and at the entrances to teahouses. Their shapes can be extraordinarily varied:

- Kasuga-dōrō (春日灯籠) – the classic of stone elegance. A hexagonal base, a roof, and a chamber adorned with motifs of deer (the messenger of the Kasuga deity), the sun, and the moon. When placed en masse at Kasuga-taisha Shrine, they create one of Japan’s most atmospheric sites.

- Ikekomi-dōrō (埋込灯籠) – the “rooted” lantern. Its shaft is sunk directly into the ground, without a visible base. It often accompanies tsukubai—stone basins used for ritual hand washing before a tea ceremony. Small and subtle, it blends almost completely into its surroundings.

- Oribe-dōrō (織部灯籠) – inspired by the eccentric tea master Furuta Oribe. It features an asymmetrical construction, unusual proportions, and window openings that often depict full and crescent moons. A symbol of the twilight of form and the search for new beauty.

▫ Portable – oki-dōrō (置き灯籠)

Small, lightweight, often made of wood or ceramic. Placed on verandas, in inner gardens, along paths leading to residences or teahouse pavilions. Sometimes they were also part of the interior—their light setting the mood for evening reading or meditation.

▫ Paper and Bamboo – chōchin (提灯), take-dōrō (竹灯籠)

▫ Paper and Bamboo – chōchin (提灯), take-dōrō (竹灯籠)

These belong to an entirely different branch of lanterns—impermanent, ephemeral, but full of charm. Chōchin are collapsible paper lanterns that light up streets during festivals. Take-dōrō, made from bamboo and paper, often appear today in modern light installations—although new, they continue the idea of simplicity and guiding light through darkness. You’ll find them in Kyoto during Hanatōro, as well as in Japanese gardens… in Warsaw.

Each type of tōrō has its place—not only in physical space but also in culture. From the monumental stones of Kasuga, through garden yukimi, to the ephemeral chōchin—all belong to the same spiritual family of light.

A Light That Guides but Does Not Illuminate – The Meaning of Tōrō

In Buddhism, the lantern’s flame is an offering of light—a gift to the Buddha, a prayer made not of words but of the quiet smoldering of life. The fire chamber—hibukuro—becomes the sacred heart of the tōrō. It symbolizes the wisdom of enlightenment, which disperses the darkness of illusion (māra) and leads to true understanding. Each lighting of such a lantern was not merely a gesture—it was a ritual of awakening.

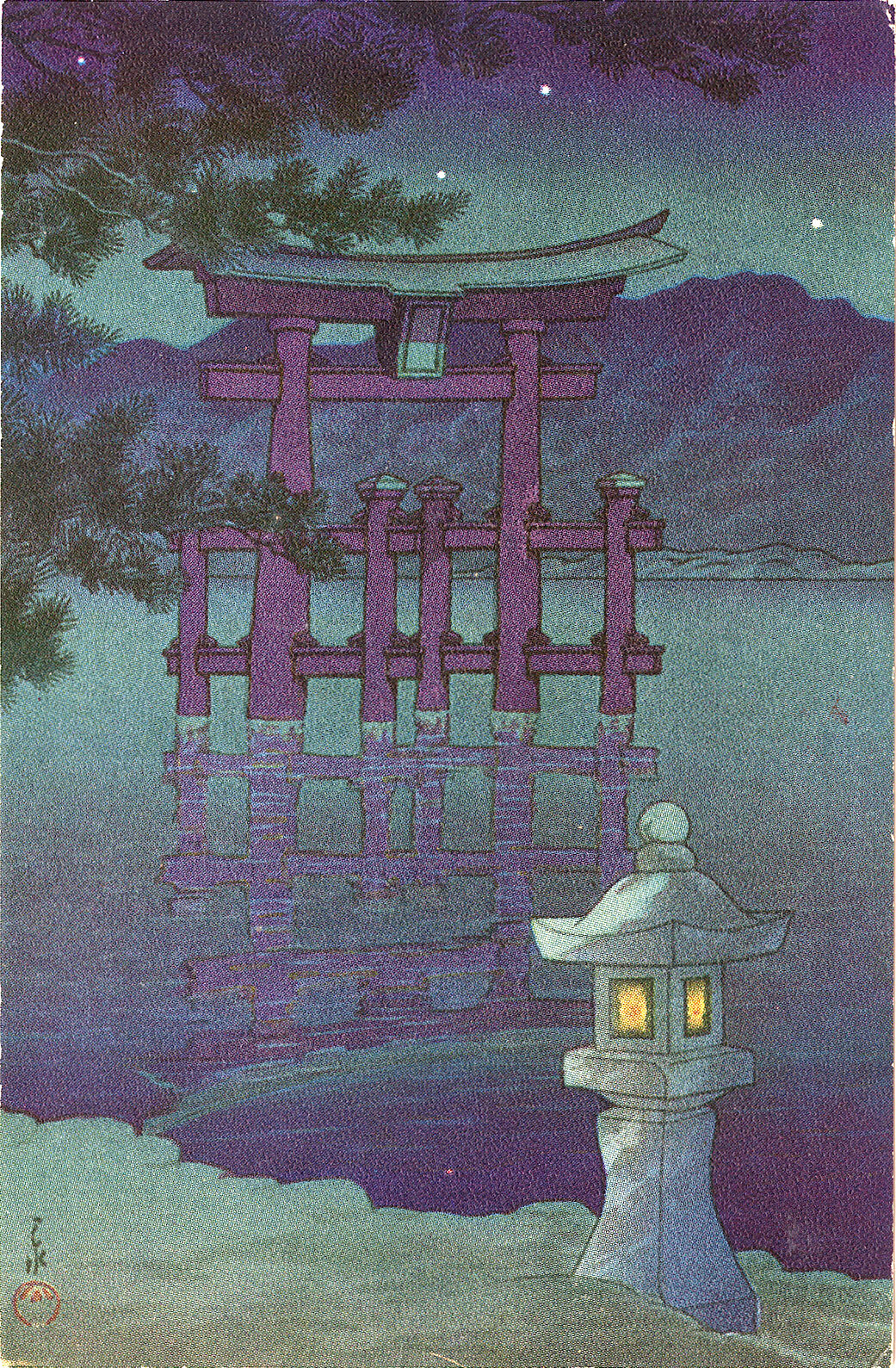

A tōrō usually stands at the threshold—between the everyday world and the sacred, between the garden and the teahouse, between clamor and silence. It is in this place—in that crack between two realities—that the moment of transition occurs. In this, they are somewhat reminiscent of torii gates (here: Torii – The Japanese Gate of Transformation). The light in a tōrō does not so much point the way as it signals: now you must enter a different state of mind. It is a moment of hesitation, of pause, of brief reflection.

In Japanese philosophy of beauty, the light of tōrō is interwoven with two key concepts: mono no aware—the gentle sorrow of transience, and mujō—the impermanence of all things. The flame in the lantern, which flickers and fades—that is life. The moss growing on the stone base—that is time. The crack in the roof—that is history.

Tōrō also embody the aesthetic of wabi-sabi—the beauty of imperfection, simplicity, humility before time. The most precious lantern is not the new one, but the old—one that has witnessed hundreds of evenings—or years. One that has blended into the landscape and become something more than an object. A stone that crumbles, and a light that fades, speak more of life than marble and electricity ever could.

In the Shadow of the Lantern Lies a Deep Social Symbolism

In Bashō’s poetry, light appears quietly, somewhere in the background of night, in the form of a lamp in a lonely monk’s hut—not as a central image, but as a half-shadow, a sign of existence and endurance amidst emptiness. This light does not illuminate the world—it exists to emphasize the darkness—the void.

Kamo no Chōmei, in his Hōjōki, writes of the impermanence of homes, cities, and fates—of all that passes like the current of a river—and yet it is within that impermanence that a lantern is lit. It stands in a tiny hut measuring ten square feet, simple, silent, as if saying: Here is a place where even a spark of meaning burns. That light—modest yet persistent—becomes a metaphor for the spirit that endures, even when the entire world seems to tremble.

Finally, in the tea ceremony, the tōrō is an essential element in constructing the roji—the path of spiritual purification. Its light is not meant for seeing, but for feeling. The flame in the tōrō does not compete with the moon—it is its humbler reflection.

And so, the stone lantern—simple and silent—becomes a symbol of nearly everything most profound in Japanese culture: impermanence, hospitality, spirituality, solitude, emptiness, and light. And that is why—though centuries have passed—it still shines today—by temples, and on the screens of video games.

Contemporary Craft – How Are Tōrō Made Today?

Of course, contemporary tōrō are not solely the realm of tradition. In Japan—but also in Europe and the U.S.—workshops exist that offer more “refined,” symmetrical replicas. These lanterns often find their way into hotel gardens and walkways, or even onto city balconies. The style may be modern, but the idea remains the same—light as a guide, as invitation, as a trace of something greater.

The light that tōrō cast is faint but true. Perhaps that is why so many people—from Tokyo to Berlin—want to have one close by: beside a path, in a garden, in the corner of a terrace. Because wherever a tōrō stands, time flows a little slower, and the night—even in our modern world—becomes just a bit more peaceful.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES

The Forgotten Torii Gate in the Concrete Underground – Amagamine Ochobo Inari

Kokedama – A Tiny Moss Planet That Brings the Forest into Our Concrete Homes

The Tradition of Kōans in Japan – A Zen Practice That Doesn’t Give Answers, But Takes Them Away

Japanese Gardens: A Piece of Art with a Surprising Ending - Discover the Secrets of Zen Gardens

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

▫ Hanging – tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠)

▫ Hanging – tsuri-dōrō (釣灯籠) ▫ Standing – dai-dōrō (台灯籠)

▫ Standing – dai-dōrō (台灯籠) ▫ Paper and Bamboo – chōchin (提灯), take-dōrō (竹灯籠)

▫ Paper and Bamboo – chōchin (提灯), take-dōrō (竹灯籠)