Wakizashi – The Smaller Cousin of the Katana That Bore the Full Weight of Samurai Honor

The True Shadow of the Samurai

Among all the swords of ancient Japan, none carried such a silent yet all-encompassing presence as the wakizashi. While pop culture has turned the sleek katana into the iconic symbol of the samurai, it was this shorter, more modest companion that served as the true witness to the warrior’s life and death. Wakizashi — literally meaning "side insertion" (脇差) — was not merely a weapon: it was a talisman of readiness, a symbol of loyalty, and the ultimate guardian of honor. Worn always close to the body, even where the katana had to be surrendered as a gesture of peace, the wakizashi remained the samurai’s closest companion — present in moments of joy, trial, and death.

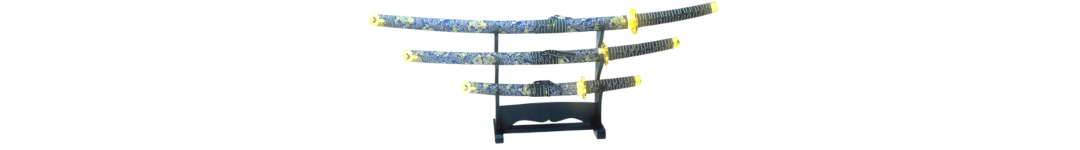

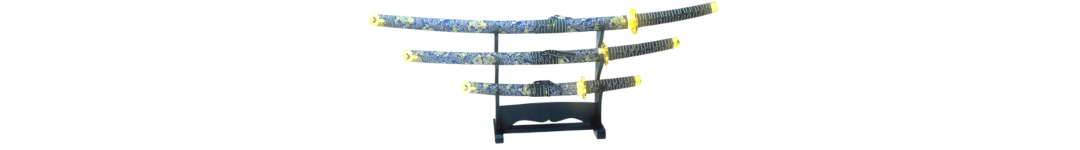

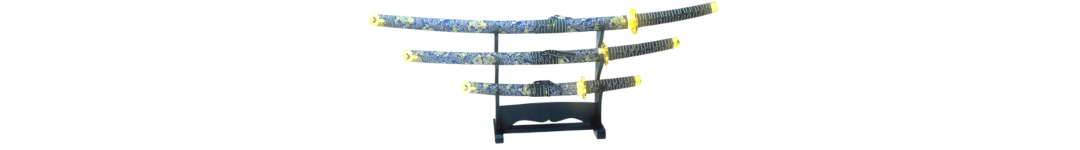

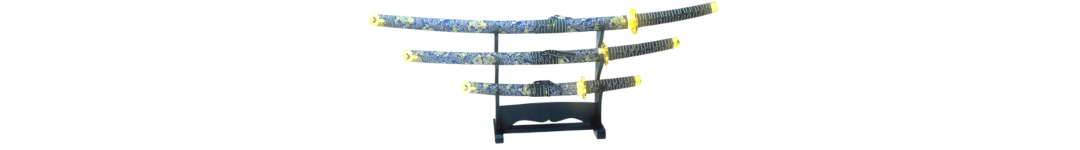

The earliest traces of the term wakizashi can be found in the turbulent chronicles of the 14th century, during the Nanbokuchō period, when short swords served both in warfare and in rites of passage. However, it was not until the Muromachi period that the wakizashi assumed its true form, becoming an integral part of Japan’s martial and ceremonial art. Forged from the same components as the katana — the tsuka (hilt) wrapped in ray skin and silk, the richly decorated tsuba (handguard), and the saya (scabbard) lacquered with urushi — the wakizashi differed in proportions and length (30–60 cm), as well as its slimmer profile, adapted for combat in tight spaces, corridors, and crowds.

Yet it was neither technique nor craftsmanship alone that made the wakizashi what it remains in Japanese memory. Its greatest strength lay in the deep, almost religious bond it shared with its owner. From the first sword received during the genpuku coming-of-age ceremony, through daily service at the side of a daimyo, to the final act of life — the ritual of seppuku — the wakizashi bore witness to every step of the samurai’s journey. It was his shadow and his heart. His blade, and his conscience. Let us now explore it more closely.

The Name "Wakizashi"

Meaning

Among the weapons carried by samurai, few bear such a silent, yet profoundly deep meaning in actual Japanese culture — and such little attention in pop culture — as the wakizashi (脇差). The very name of this blade encapsulates its function and its place in the life of a warrior. The word 脇差 (wakizashi) is composed of two kanji characters:

○ 脇 (waki) – "side" or "flank," indicating the place where the blade was worn,

○ 差 (sasu) – "to insert," "to pierce," or "to carry" — a verb with a physical, dynamic nuance, suggesting not just passive carrying of the weapon but readiness for immediate action.

The wakizashi was a companion sword, but not in a secondary sense — it was a personal weapon, a soul within arm’s reach, concealed at the samurai’s side, always ready for instant motion, even when the katana could not be drawn or was unavailable.

First Appearance in Written Sources

Traces of the name "wakizashi" can be found as early as the tumultuous Nanbokuchō period (南北朝時代, 1336–1392), when Japan was torn between two imperial courts: the Northern and the Southern. In one of the most important works of that era — the war chronicle Taiheiki (太平記) — references appear to 脇差の刀 (wakizashi no katana), meaning "swords carried at the side."

At that time, however, the term wakizashi did not yet refer exclusively to the specific type of sword we know today. It was a more general designation for short side arms, which samurai often carried under their armor (yoroi) or beneath the folds of ceremonial robes (hitatare). It could refer to a tantō (短刀 – a short combat dagger) or a small uchigatana (打刀) intended for close-quarters fighting.

Over the following centuries, as the form and function of swords became more standardized — especially during the Muromachi period (1336–1573) and later the Sengoku period (1467–1615) — the term wakizashi came to denote a clearly defined category of weapon: a shorter sword worn alongside the katana, forming the famed daishō (大小) — "large and small" (more about this here: Discover the Katana – The Birth, Maturity, Wartime Life, and Noble Old Age of the Samurai Sword).

It is also worth noting that the original meaning of the term wakizashi was not confined solely to blade length. It also referred to the method of carrying — at the side (not on the back or elsewhere) — and the readiness to draw the weapon instantly in the face of danger, without the need to unfasten or remove complicated harnesses.

Characteristic Features of the Wakizashi

Types

Although the wakizashi often remains in the shadow of its longer companion, the katana, it is a work of precision, refinement, and crucial practical function. Seemingly simple — it actually encapsulates both the artistry of Japanese swordsmithing and the philosophy of samurai life.

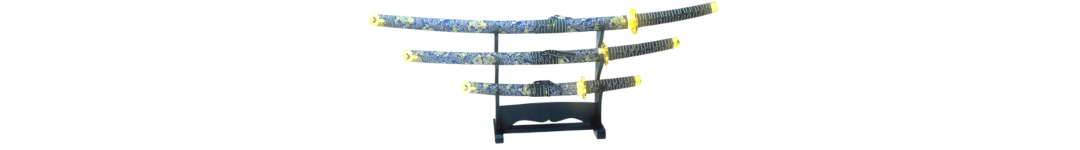

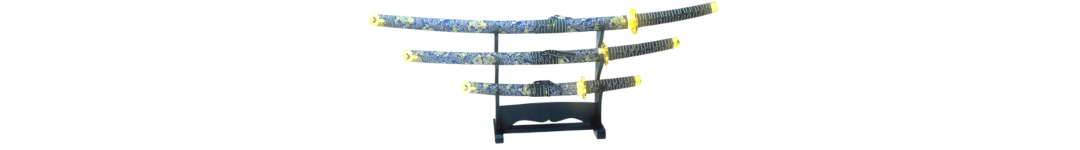

The blade length of the wakizashi usually ranges from 30 to 60 centimeters, depending on the period, intended use, and the owner’s personal preference. Three main types were distinguished: ► Ko-wakizashi (小脇差) — small, shorter than 40 cm,

► Chū-wakizashi (中脇差) — medium, 40–54.5 cm,

► Ō-wakizashi (大脇差) — large, reaching up to 60.6 cm.

An intriguing fact is that some ō-wakizashi were nearly as long as shorter katana — and were employed in dual-wielding techniques such as Niten Ichi-ryū (the fencing school of Miyamoto Musashi — more about him here: The Most Important Lesson from Musashi: "In all things have no preferences" (Dokkōdō) and here: Mastering One’s Desires: The Solitary Path of Musashi and Aurelius).

The blade shape of the wakizashi faithfully mirrors that of the katana — gently curved and single-edged, although in a slimmer, more compact form. A characteristic feature of its construction is that the blade was often slightly thinner, and its cross-section narrower than the katana’s, granting it greater sharpness but also making it more susceptible to damage during brutal combat.

Anatomy

Each wakizashi was composed of elements that served both practical purposes and reflected the owner’s status:

► Tsuba (鍔) – the handguard, taking various shapes: round (maru-gata), rectangular (kaku-gata), or more imaginative. Unlike the large, heavy tsuba of katana, those used for wakizashi were often smaller and more delicate, richly adorned with motifs of nature, dragons, or family crests (mon 紋) — more about Japanese family crests (kamon) here: Kamon of 15 Strongest Samurai Clans of Japan.

► Tsuka (柄) – the hilt, typically made of magnolia wood, wrapped with ray skin (samegawa 鮫皮) and meticulously bound with silk or cotton cord (tsukamaki). Although theoretically allowing for two-handed grip, in practice, the wakizashi was primarily wielded one-handed, emphasizing speed and precision.

► Saya (鞘) – the scabbard, made of wood, lacquered with urushi, and sometimes inlaid with mother-of-pearl or gold. As a personal weapon worn even indoors, wakizashi scabbards were often adorned even more elaborately than those of katana — the scabbard was not only a protective sheath but also a symbol of the owner's status.

► Nakago (茎) – the tang hidden inside the hilt, bearing the swordsmith’s signature (mei 銘). For connoisseurs and collectors, it is often this invisible part of the sword that attests to the authenticity and craftsmanship of the blade.

Other Features

The wakizashi differed from the katana not only in length. The differences ran deeper and were tied to functionality.

The wakizashi had a shorter blade and lighter construction, making it an ideal tool for fighting in confined spaces — castles, residences, narrow corridors, and even during ritual ceremonies. In daily practice, its constant presence at the samurai’s side played a crucial role — unlike the katana, which, according to etiquette, had to be left at the entrance of a home or castle.

It is also worth noting the proportions between the hilt and the blade. In the katana, the hilt often measured about one-third of the blade's length, whereas in the wakizashi, the hilt was relatively longer compared to the shorter blade, providing greater control for quick draws and precise strikes.

An interesting construction detail is that some wakizashi, much like tantō, were crafted in the hira-zukuri (平造り) style — without the characteristic ridge line (shinogi), which made the blade even slimmer and better suited for cutting in tight quarters. Others, however, imitated the katana’s form in the shinogi-zukuri (鎬造り) style, giving the blade a distinct ridge line and strengthening its structure.

We must not forget details such as the koiguchi (鯉口 – "carp’s mouth") — the opening of the scabbard where the blade fit perfectly — or the sageo (下緒) — the decorative cord tied to the saya, used to fasten the scabbard to the obi (帯), the traditional belt.

Thus, despite its modest size, the wakizashi was a miniature embodiment of everything most essential in a Japanese sword: elegance of form, deadly functionality, and profound symbolism. Every part of it — from the thin hamon line revealing the style of blade hardening to the intricate decorations of the tsuba — reflected the samurai’s philosophy: being ready for anything, yet always preserving beauty and harmony.

Wakizashi — What Did It Truly Represent?

Wakizashi as the "Inner Sword" (内刀)

In the world of the samurai, every gesture, every object, every rule carried profound meaning, rooted in philosophy and ceremony. The wakizashi, shorter and lighter than the katana, served a role far more important than that of a mere backup weapon — it was the "inner sword," a symbol of personal vigilance, readiness, and the unbroken connection to one’s honor.

When entering the castle of a daimyō (大名) or the residence of another samurai, a warrior was obliged to lay his katana on a special stand — the katana-kake (刀掛け). This was not only an act of observing etiquette (reihō, 礼法) but also a demonstration of peace and trust toward the host. The katana, as a weapon of death, could not cross the threshold without explicit permission. The wakizashi, however, always remained at the warrior’s side.

It was understood that although a samurai lived by the code of bushidō (武士道), not everyone around him could be trusted to uphold the same standards of honor. A single treacherous move, one false word — and life could end in the blink of an eye. Thus, the wakizashi became an extension of the survival instinct, a tool kept close even when the world around seemed friendly — for friendship could often prove illusory.

In traditional accounts — such as those recorded in Nihon Budō Shiryō (日本武道資料) — it is repeatedly emphasized that a true samurai never parted from his blade, even for a moment. During meals, ceremonies, moments of rest — the wakizashi lay within reach, ready to be drawn in an instant.

Moreover, the manner of carrying the wakizashi — blade facing upward, with the hilt slightly tilted to the right — symbolized not only readiness but also restraint. In samurai culture, showing that the blade could be drawn with a single movement, yet refraining from doing so, was a display of spiritual strength and self-control.

For the samurai, the wakizashi was a "soul within arm’s reach" — an object of daily communion with one’s own mortality and a constant readiness for whatever fate might bring. In that silent presence at the hip lay nothing less than an entire philosophy of life lived "on the edge."

Wakizashi and Honor

However, the most profound significance of the wakizashi revealed itself in final moments: when the samurai faced the loss of honor, when he had failed his lord, when a battle was lost, or when orders demanded death.

It was then that the wakizashi became the instrument of seppuku (切腹) — the ritual suicide, an act of redemption meant to cleanse disgrace and preserve the dignity of one’s lineage (more about this here: Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?).

Seppuku was a singular ceremony. The samurai would sit in the seiza position, often dressed in formal attire (kamishimo). Before him would be placed a carefully prepared wakizashi or a shorter tantō, and beside him stood the kaishakunin — the second warrior, whose duty was to deliver the coup de grâce, severing the head to shorten suffering.

Contrary to images perpetuated by cinema, proper seppuku was not a brutal act of death, but a demonstration of ultimate discipline and self-control. The wakizashi blade was to be thrust deeply below the navel, then drawn horizontally to the left; if strength permitted, the samurai would attempt to cut to the right as well, forming a T-shape. This gesture, performed in silence and concentration, was meant to prove courage, mastery over pain, and ultimate obedience to the code of honor.

It is worth noting that for women of samurai lineage, the ritual was different: Women, defending their honor, typically used a tantō — a shorter dagger — to either cut their throat or stab their heart.

Wakizashi as an Element of Ceremonies and Rituals

In the life of a samurai, nothing was accidental. Every stage of existence — from birth to death — was bound to specific rituals, and within these rites, the wakizashi played the role of a discreet yet inseparable companion.

In samurai families, boys were given a small wakizashi or tantō from a very young age, often during a ceremony called genpuku (元服) — a coming-of-age ritual usually held between the ages of 12 and 16 (the exact age depending on the prefecture and clan). The gift of a weapon was not merely a present — it was the passing on of responsibility for one's own life, honor, and future service.

When a young warrior took on the duty of serving his daimyō or directly the shōgun, the wakizashi became a visible symbol of his devotion. Bearing arms was not just a right, but an obligation. The daishō (大小) — the paired katana and wakizashi — sealed this bond: the swords became the warrior's body and shadow.

Ceremonies marking a samurai’s retirement, his transition into monkhood (many renowned warriors ended their lives as monks), or his preparation for death — all included the symbolic handing over or dedication of the wakizashi. In the hands of descendants, this weapon lived on as a talisman of memory, a fragment of the ancestor’s soul encapsulated in steel.

Wakizashi as the "Guardian of the Soul"

In the Japanese worldview, weapons were not merely objects — they were extensions of the soul. The wakizashi, much more personal than the heavier katana, symbolized not only physical strength but also inner vigilance, readiness, and the ability to preserve oneself even in a world rife with betrayal.

A samurai did not regard his wakizashi as a mere tool of war — he treated it as a living companion, almost a trusted friend at his side. In martial arts, such as certain branches of kenjutsu and iaidō, special training was devoted exclusively to the wakizashi.

These exercises did not aim to cultivate brute strength but rather sharpness of perception, reflexes, and the readiness to act under the least favorable conditions.

In schools like Yagyū Shinkage-ryū (柳生新陰流), the ability to draw the short sword in a fraction of a second was considered the pinnacle of mastery — not just of technique, but of an ever-alert spirit (zanshin, 残心).

Social Status and Symbol of Class

In feudal Japan, where attire, speech patterns, and even the type of footwear indicated social status, the daishō — the katana and wakizashi worn together — served as an unmistakable sign of belonging to the samurai class (buke, 武家).

No peasant, artisan, or townsman had the right to wear such a pair of swords. While carrying a wakizashi alone was permitted to certain higher-ranking townspeople (though their swords were more modest), the complete daishō, with both katana and wakizashi, was an exclusive privilege of the samurai — his calling card, his inseparable uniform.

Interestingly, during the peaceful Edo period (1603–1868), the wakizashi also began to take on a decorative role. The more Japan stabilized, the more ornate the scabbards (saya), hilts (tsuka), ornaments (menuki), and guards (tsuba) became. Masters of the tsuba, such as the artisans of the Goto family, created miniature works of art — golden dragons, swaying grasses, mythical beasts — which adorned the wakizashi, turning it into an object of pride and personal prestige.

For a samurai, the decoration of his wakizashi spoke volumes about his character: humility or pride, a love of nature or a fascination with the supernatural — all of it was inscribed into a single short blade.

A Symbol of Life and Death

The wakizashi was like a compass pointing north amid the storms of life. In daily reality — it served survival: when, in the tight alleyways of a castle or the crowded streets of Edo, an enemy reached for a hidden blade, it was the wakizashi that decided within a fraction of a second whether life would be preserved or lost.

But just as often, the wakizashi became the last line of defense for honor. When betrayal, disgrace, or defeat closed all roads, it was this short blade that allowed the samurai to depart with dignity, in the act of seppuku. Thus, the wakizashi was not merely a weapon — it was a bridge between life and death, a witness to all the dramas of a samurai’s fate.

In many legends and tales, it is said that the soul of a samurai lingers around his wakizashi even after death — as if this small sword held the warrior’s final breath within its steel.

The History of the Wakizashi

Amid all the weight the wakizashi carried in the world of values, ceremonies, and personal honor, one must not forget that this sword also followed its own long historical path. Its symbolism, its place at the samurai’s side — all echoed the epochs and turbulent transformations of Japan.

To fully understand the wakizashi, we must return to the times when its form was first taking shape — an era when the lands of Japan were mired in endless warfare.

Beginnings — The Chaos of War

The wakizashi, in its characteristic form, began to emerge in the 15th and 16th centuries, during the late Muromachi period (1336–1573) and the Sengoku era (戦国時代, "The Age of Warring States"). This was a time when Japan fractured into dozens of rival domains, and war became the norm. It was an age when, for several generations, it was unimaginable even to dream of a world without conflict.

Earlier forms of sidearms — short swords like the tantō or uchigatana — were not yet what the wakizashi would become. It was precisely in the brutal, dynamic clashes — battles fought in castle corridors, street skirmishes, and ambushes in dense forests — that samurai began carrying a second sword: shorter, lighter, and more maneuverable. It was this practical necessity that gave birth to the wakizashi as a distinct class of weapon.

Interestingly, the term "脇差" (wakizashi) first appears in written sources during the Nanbokuchō period (14th century), for example in the Taiheiki (太平記), but at that time it referred more generally to the idea of "a weapon worn at the side" — not necessarily to the fully formed, distinct wakizashi we recognize today.

Initially, there was no standard: short swords of various lengths and shapes were carried, and the terminology remained fluid. A warrior might carry a shorter version of an uchigatana, a longer tantō, or something we would today classify as a wakizashi.

Formalization During the Edo Period

The true flourishing of the wakizashi came with the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868), when Japan, after decades of chaos, was unified and new social regulations were introduced.

Under the buke shohatto (武家諸法度) — an edict regulating the lives of samurai — the authorities mandated that samurai must carry a daishō, a pair of swords: ► The katana as the primary weapon (honzashi, 本差), ► The wakizashi as the auxiliary weapon (wakizashi, 脇差).

Moreover, the shogunate established clear standards for blade length: ► The wakizashi was to have a blade length between 1 and 2 shaku (approximately 30 to 60 centimeters).

This regulation not only standardized the construction of the wakizashi but also sanctified its symbolism as an integral part of the samurai's image. An interesting detail is that in the formal records of the Edo period, the katana and wakizashi were treated as an inseparable pair, and a samurai deprived of his daishō, even temporarily, lost an essential part of his social identity.

Role in Warfare

Although the Edo period was relatively peaceful, the preceding centuries had been marked by constant conflict, where the wakizashi played a significant combat role. In battle conditions, when the katana might be broken or lost, it was the wakizashi that became the warrior's last resort. Its shorter length made it ideal for fighting:

- in castle corridors,

- inside buildings,

- in dense forests,

- during boarding actions on ships — as occurred during the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, and later during pirate skirmishes fought on cramped decks (read more here: Wakou – Pirate Freedom, Independence, and Terror on the Seas of Japan, Korea, and China and here: Japanese Pirates of the Murakami Clan: Educated Samurai, Bandits, Entrepreneurs, Poets – Who Were They?).

Moreover, in some schools of combat, such as the aforementioned Niten Ichi-ryū, techniques of throwing the wakizashi were taught: the short sword could be hurled at an opponent, opening the way for an attack with the katana or a swift shift of initiative.

Proliferation: Wakizashi Among the Townspeople

Unlike the katana, which was reserved exclusively for samurai, the wakizashi was more accessible to other layers of society. Merchants (shōnin, 商人), artisans (shokunin, 職人), and wealthier townsmen could carry a wakizashi as a means of self-defense, particularly during times when banditry posed a real threat along trade routes.

Of course, their wakizashi were less ornate and shorter, and the right to carry weapons was subject to strict local restrictions.

In the criminal underworld — among the bakuto (博徒, gamblers) and later also the yakuza (やくざ) — so-called "long wakizashi" (naga-wakizashi, 長脇差) gained popularity, swords whose length was nearly at the upper limit for wakizashi, symbolizing strength and prestige within unofficial social structures (read more about the origins of the yakuza here: What is the Yakuza? - Can One Be a Bloody Gangster, Honorable Samurai, Drug Baron, and Contemporary Robin Hood All in One? and about its decline here: How the Mighty Yakuza was Tamed in the 21st Century. And What Sumo Tournaments Have to Do with It?).

Conclusion

Although today the wakizashi rests mainly in museum displays and private collections, its spirit has not faded. This short sword remains a symbol of something that continues to live in Japanese culture: readiness for the inevitable changes of fate, respect for danger, and profound inner discipline. The wakizashi teaches us that strength does not always lie in size or brutal power — sometimes the deepest meanings are contained within what is quiet, humble, yet always close to the heart.

In the samurai era, the wakizashi was not just a weapon — it was the personal guardian of dignity, the silent witness to decisions of life and death, the material embodiment of the spirit of bushidō. Perhaps that is why, even today, in a world where we no longer wear swords at our sides, the memory of the wakizashi still stirs the imagination — as a reminder of courage, readiness, and inner strength.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Men Yoroi: Wrathful and Impenetrable Battle Masks of the Samurai

Japanese Weaponry Under the Microscope: Dissection of a Samurai's Armor

Muramasa's Bloody Blades – The History of Japan in the Shadow of a Cursed Katana

Raikirimaru – The Katana of the Tachibana Clan That Cut Through Lightning

Samurai War Banners: Japanese Heraldry Under Which Battles Were Fought

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!