Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?

Honorable Cutting

In today's article, we will discuss in detail what seppuku was, the ritual of the samurai's suicide, who performed it and why, and what significance the ceremony held. Once we have this knowledge – we will share three stories of samurais who committed seppuku: Minamoto no Yorimasa – the first (documented) samurai who ritually sacrificed his life in the name of the Bushido code; Saigō Takamori – the last known samurai who also ended his life in this brutal way; and Yukio Mishima – a 20th-century writer (Nobel Prize nominee), who also committed suicide by hara-kiri cutting.

Harakiri and Seppuku – What Do These Words Mean?

Harakiri (腹切り)

Harakiri (腹切り)

Although often used interchangeably, the words "harakiri" and "seppuku" differ in meaning and context. "Harakiri" (腹切り), which literally means "belly cutting," is a more colloquial term often used outside of Japan. It is the name of the act itself. This concept simply describes the method of causing death – by cutting open the belly. 腹 (hara) - means "belly." In Japanese culture, the belly is often considered the seat of the spirit and emotions, so its cutting kills the spirit, the human emotions. 切り (kiri) - Means "cutting," "to cut." This kanji refers to the act of cutting or slicing.

Seppuku (切腹)

The term "seppuku" (切腹), which can also be translated as "belly cutting," is more formal and used in the legal and historical language in Japan. Seppuku refers to a more organized and ceremonial act of suicide, which was legally regulated and could be imposed as a form of punishment. 切 (setsu) - Means "cutting" or "to cut." It is the kanji that refers to the act of cutting. 腹 (fuku) - also means "belly," similar to in harakiri. It symbolizes the place that is the subject of the ritual cutting during seppuku.

Thus, hara-kiri is the name of the act of committing suicide by cutting open the belly. Seppuku, on the other hand, denotes the formal act of a samurai's suicide by performing a specific ritual, the completion of a traditional ceremony, which ends with suicide through hara-kiri (belly cutting).

The Hidden Meaning in the Order of the Kanji

The Hidden Meaning in the Order of the Kanji

The kanji for "harakiri" and "seppuku" have a different order, which has profound symbolic meaning:

□ Harakiri (腹切り): "Hara" (腹) means belly, and "kiri" (切り) means cutting. It focuses on the act of cutting itself.

□ Seppuku (切腹): "Setsu" (切) means cutting, and "fuku" (腹) means belly. It focuses on the ceremony and context of suicide.

The symbolism of these characters emphasizes the difference in perception of these two actions. Seppuku, with its inversion of words, suggests greater formality and connection to the process, while harakiri, with its direct reference to "belly cutting," may seem more direct and brutal.

Other Terms Related to Ritual Suicide

Refers to the female version of seppuku, often committed by the wives of samurais who wanted to avoid captivity or disgrace (what disgrace could meet her after the death of her husband at the hands of his enemies everyone can supplement). Jigai was usually performed by cutting the neck arteries with a knife.

□ Ji (自) - means "self-", "personal," "own." It is a prefix indicating something that is done by the person themselves, without anyone else's help.

□ Gai (害) - means "harm," "injury," "damage." In the context of jigai, it refers to the harm that a woman inflicts on herself.

Together, 自害 (jigai) literally means "self-mutilation" or "self-destruction."

Traditionally, the seppuku ritual, with its brutal belly cutting, was reserved for men, mainly samurais, who thus demonstrated their courage and determination, as well as care for maintaining honor. Women, associated with the same social class, also committed suicides for similar reasons, but their form was less drastic.

This is a form of enforced seppuku, which was ordered for samurais as a punishment for serious offenses or betrayal. Tsumebara, as a punitive ritual, was much more humiliating than voluntary seppuku, as the samurai had no chance to regain honor by taking their own life.

□ 詰 (tsume) - Means "to close," "to block," "to fill," or "to complete." This character may also refer to a forced or final situation.

□ 腹 (hara) - Means "belly." It is the same character that appears in the terms "harakiri" (腹切り) and "seppuku" (切腹), referring to the area of the body that is the subject of the ritual cutting.

Although tsumebara resembled seppuku in terms of ceremony, it was often more degrading, reminding that it was a punishment, not an honorable suicide. A samurai could be forced into the act in less honorable circumstances and with less ceremony. The goal, apart from the obvious punishment of the samurai, was also to warn others, emphasizing the severity of the consequences of betrayal or other serious offenses.

Description of the Seppuku Ritual

Organization

Organization

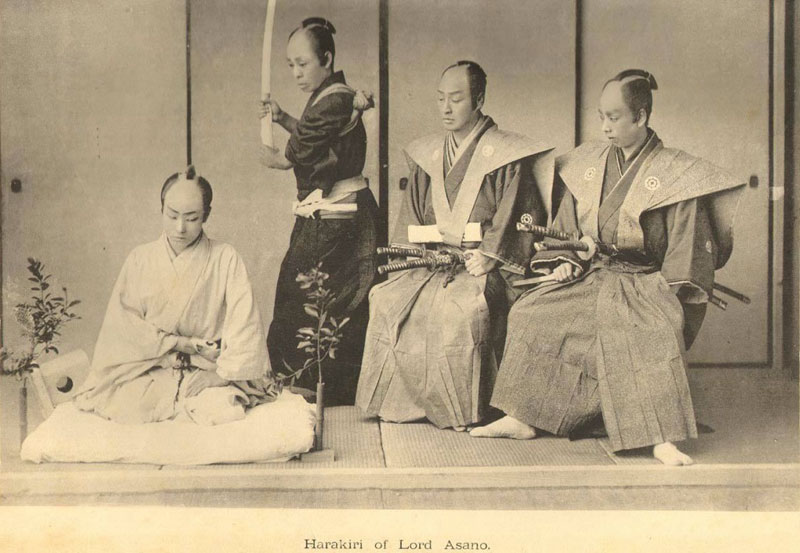

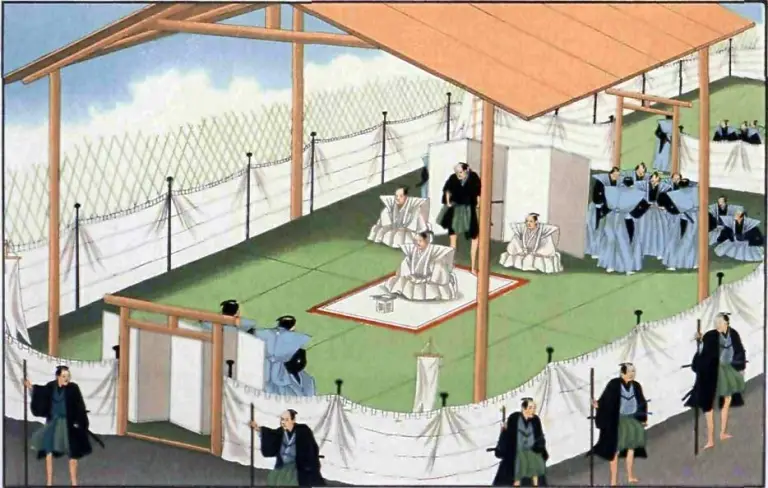

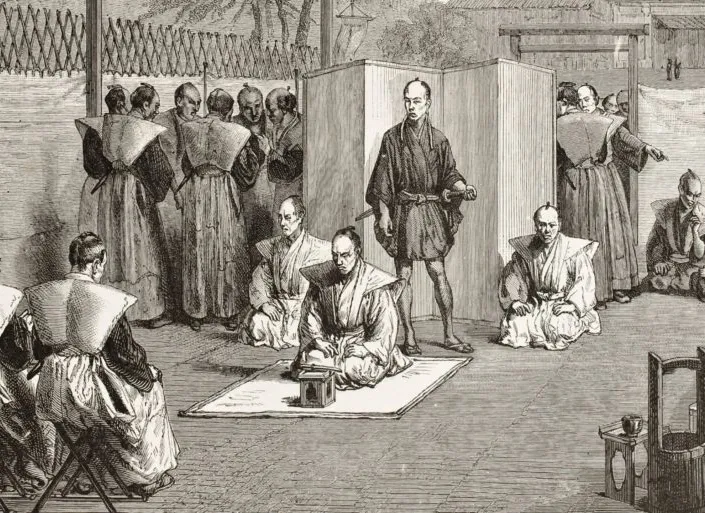

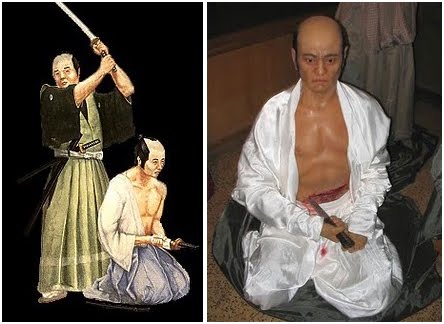

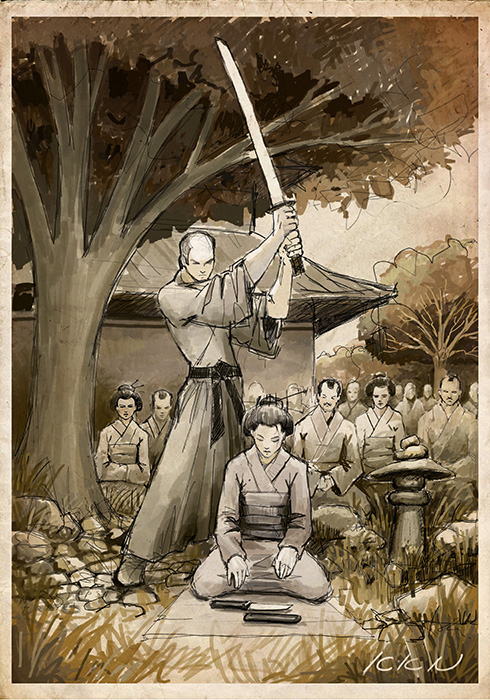

The ceremony began by choosing an appropriate place and time, often in the presence of witnesses, but away from the public eye. The samurai, dressed in a white kimono – a symbol of purity and death – would consume his last meal and then drink sake. This moment, as Maurice Pinguet points out in his book "Voluntary Death in Japan," was to be filled with deep reflection on life and death.

Having spiritually prepared, the samurai would sit on a cushion in the seiza position (on his knees, with buttocks resting on the heels - 正座, lit. "correct sitting"). Before him, a white paper was placed on which he would write his jisei (辞世 – lit. "farewell to the world") – a death poem, being his final words. After writing the jisei, he would bare his torso, and a tantō (短刀, lit. "short sword"), a specially prepared knife, was handed to him.

Scene

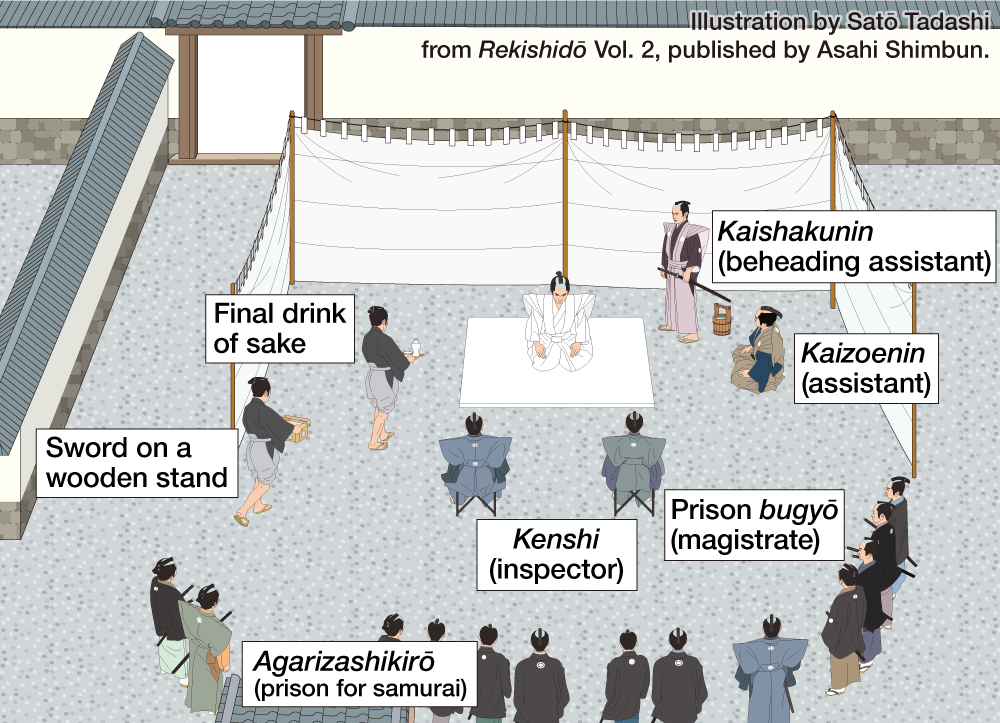

The seppuku ceremony was a highly ritualized act, and each participant had a specific role and place. The samurai performing seppuku took a central position on the mat, dressed in a white kimono, symbolizing the purity of intent and readiness to pass to the other side. In front of him, on a wooden stand, was the sword – tantō, the tool with which he would make the ritual cut.

On one side of the samurai was the kaishakunin, an assistant responsible for decapitation, who respectfully observed the proceedings, ready to act when the samurai completed his cut. His role was extremely important and required not only precision but also exceptional composure to provide the samurai with a dignified and quick death.

On the other side of the samurai were the assistants, usually members of his family or close companions. One of them, the kaiōenin, was an attendant who took care of the details of the ceremony, including serving the last cup of sake to the samurai, symbolizing the final stage of life before death.

Next to the place designated for the samurai, usually at a lower level, were the ceremony's inspector, the kenshi, responsible for supervising the proper conduct of the ritual, and the prison officers, bugyō, who oversaw the process if the seppuku took place in the context of a sentence being carried out.

Each participant of the ceremony played their role, and their precise placement and behavior were strictly regulated by the ritual, which gave this moment a special weight and significance. The proper organization and ritual process of seppuku were intended to help the samurai maintain dignity and honor in the face of death.

The samurai would insert the blade into the left side of the abdomen, sliding it to the right and then directing it upwards, creating a shape similar to the letter "L." This painful act was full of symbolic meaning, as Nitobe Inazō explains in "Bushidō: The Soul of Japan," signifying not only death but also birth to a new life in the afterlife.

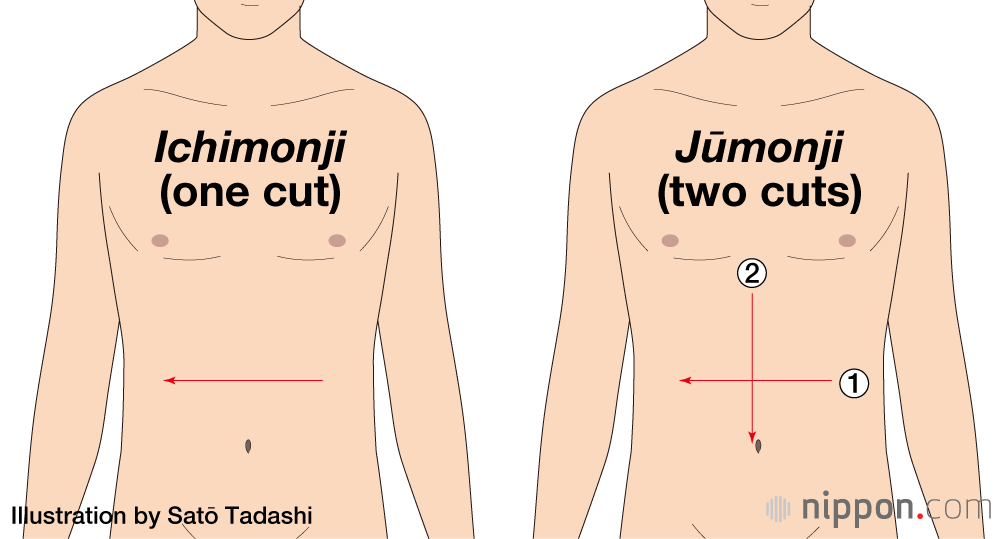

Cutting

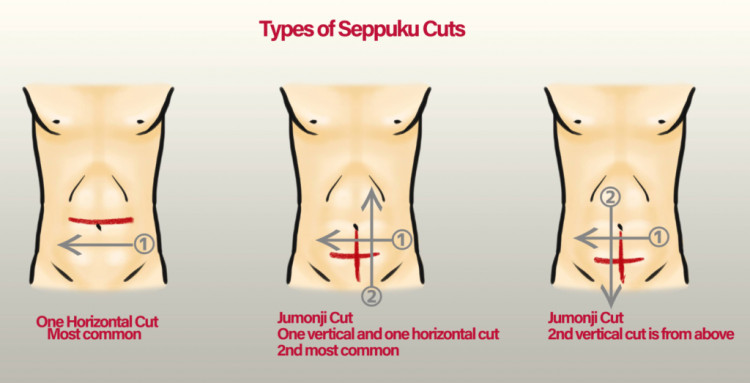

The ritual of seppuku involved performing a very specific, ritual cut, the form of which was determined by tradition and circumstances. The two main methods of cutting the belly during seppuku were ichimonji and jūmonji, each carrying its own symbolic and practical implications.

Ichimonji (一文字)

Ichimonji, meaning "one character" or "straight line," was a method in which the samurai performed a single, horizontal cut from the left to the right side of the belly. This cut, as the illustration shows, sliced across the belly just under the rib line, deeply but not enough to cause instant death. This technique was designed to give the samurai enough time to confront the pain and death, considered the ultimate test of courage and perseverance.

Jūmonji, literally "ten characters" or "cross," required performing two cuts: first the horizontal ichimonji cut, then the samurai had to reinsert the blade and cut the belly vertically from top to bottom. The second cut, which usually started at the intersection with the first cut, caused a quicker death than the single ichimonji cut, although it was performed less frequently due to the associated pain.

Both cutting methods in the seppuku ritual were symbolic and held deep meaning in the culture of Japanese samurais. The way a samurai performed the cut reflected his determination, courage, and level of acceptance of his fate, serving as the ultimate testament to his life and values.

The Role of the Kaishakunin (介錯人)

As a silent witness to the samurai's suffering and determination, the kaishakunin was ready to act to spare the samurai further torment once he had made his cut.

Variants of the Ritual Depending on the Performer's Status and Gender

Variants of the Ritual Depending on the Performer's Status and Gender

Seppuku was not limited to men; women associated with samurais could also choose death by jigai, especially in cases of the threat of capture or disgrace. However, their method differed; instead of cutting the belly, they often cut the veins in their neck.

Social status also influenced the course of the ceremony. Higher-ranking samurais had more complex seppuku ceremonies, often in the presence of more witnesses and with greater pomp, emphasizing their significance and social role.

The Profile of the Suicide

Who?

Seppuku was primarily reserved for samurais, the warrior class in feudal Japan. Although mainly associated with men, women from their families sometimes chose this form of suicide, especially when they wanted to avoid disgrace or captivity after a lost battle or the fall of their clan. An example of such a situation was the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, which decided the political landscape of Japan for the next centuries, leading to suicides among the defeated sides, both men, and women.

The Battle of Sekigahara was a turning point that consolidated power in the hands of Tokugawa Ieyasu and his allies, leading to about 300 years of peace and stability under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. As a result of this battle, many daimyō (feudal lords) and samurais found themselves on the losing side, which often meant the loss of land, status, and honor. Although such statistics were, of course, not kept, based on contemporary knowledge and literature, we can estimate that after such a drastic coup and reshuffling of power, up to three hundred high-ranking daimyō, their samurais, and family members (women) may have resorted to suicide by seppuku.

Why?

Why?

For samurais, harakiri was not just an act of death, but a ritual full of deep cultural and spiritual significance, aimed at restoring or maintaining family honor. This fact was of immense importance not only for the samurai himself but also for his family, affecting their social status and future generations.

Certainly not insignificant was the fact that the family of a samurai, who died honorably, could expect to maintain their social position and avoid repercussions, whereas in the opposite case, misfortune could befall not only the samurai himself but his entire family. Thus, it can also be considered that seppuku was sometimes the only way out of a situation where the life of the samurai and his family was threatened. Through honorable suicide, the samurai could protect his wife and children from death or disgrace.

Three People, Three Stories of Seppuku

Three People, Three Stories of Seppuku

In the history of Japan, seppuku served many functions – from the ultimate accent of loyalty to the lord, through an act of protest, to a means of punishment for transgressions or a way to save the family. Regardless of the reasons, each case of seppuku leaves behind a story of pain, honor, and often tragedy, shedding light on the complex nature of human dignity and cultural identity.

To better understand this phenomenon, let us look at three cases from three different epochs when someone voluntarily committed suicide, called seppuku, in the name of honor, however understood: Minamoto no Yorimasa, who was one of the first documented cases of seppuku; Saigō Takamori, known as the last samurai, whose death symbolizes the end of the samurai era; and Yukio Mishima, a 20th-century writer and thinker, whose dramatic life and spectacular death resonated around the world, serving as a symbolic commentary on modern Japan's struggles with its traditions.

Each of these stories not only reveals personal drama but also pivotal moments in the history of Japanese culture, showing how deeply seppuku is rooted in national consciousness and values.

The Story of Minamoto no Yorimasa (1104-1180)

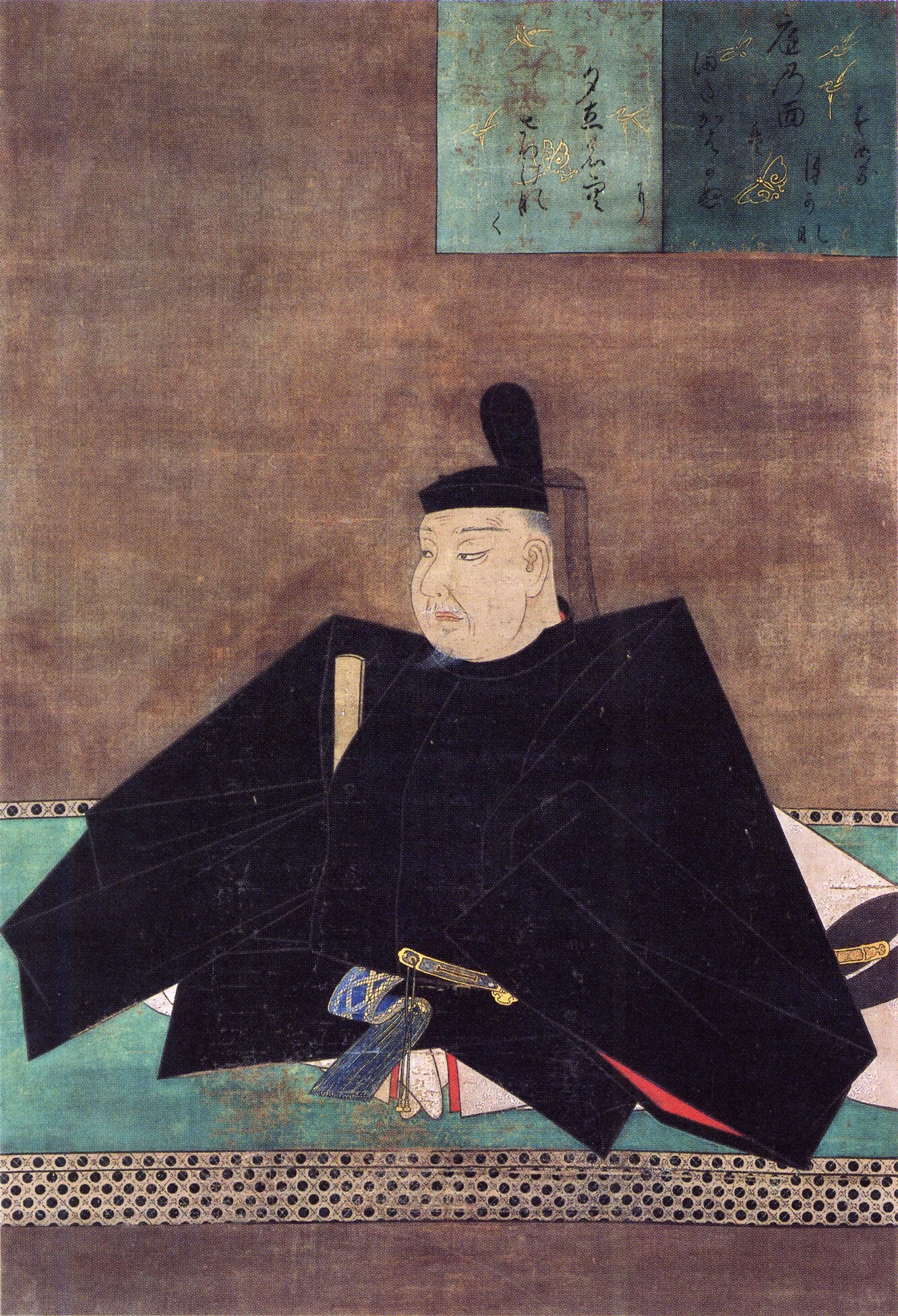

Yorimasa was not only a distinguished warrior and strategist but also a respected poet. His skills and devotion to the emperor quickly earned him position and respect. However, his life and career were unexpectedly transformed by the escalating conflict between the two dominant clans. In 1156, during the Hōgen Rebellion, Yorimasa sided with the imperial cause, but the rising power of the Taira clan meant his position hung by a thread.

The Battle of Uji in June 1180 became the culmination of the conflict. It marked the beginning of the Genpei War, a series of fierce clashes between the Minamoto and Taira clans. Yorimasa led the defense of the strategically key Uji Bridge, which the Taira sought to capture. Despite a heroic defense, Minamoto forces were overwhelmed by the numerically superior Taira troops.

As a samurai, Yorimasa was raised in the spirit of bushidō, the samurai code, which dictated that honor was more valuable than life. Confronted with the defeat experienced during the Battle of Uji, the loss of honor was worse for him than death. The code compelled warriors to choose an honorable death when faced with inevitable defeat to avoid disgrace and loss of face, which also had a direct impact on the future position of his family, who avoided ostracism and life in disgrace thanks to his act of seppuku. For Yorimasa, seppuku was not just an act of desperation but a conscious choice that also protected his children and grandchildren.

Perhaps Yorimasa also saw this as a form of transcendence—separating his spirit from the physical conditions of earthly existence. His final words and poem, comparing life to the transient cherry blossoms, suggest a deep understanding of the ephemeral nature of life, a key element of Zen Buddhism and the philosophy of mono no aware. In this context, his death was not just an escape from dishonor but the ultimate act to deepen the understanding of life as a continuous cycle of birth and death, where honor and inner values remain unchanged even in the face of the inevitable variability of the world.

After his death, the Minamoto clan ultimately triumphed in the Genpei War, leading to the establishment of the first bakufu (幕府, military government), which governed Japan for the following centuries. Yorimasa remains a figure who combined literary sensitivity with warrior heroism, an eternal symbol of an era when poetry and the sword were equally valued.

The Story of Saigō Takamori (1828-1877)

His career reached its zenith when he helped overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate, leading to the restoration of imperial power in 1868. However, despite his successes, Saigō became critical of the Meiji government, which he believed had betrayed the ideals for which they fought. Concerned about Western influences and the loss of traditional samurai values, Saigō called for the protection of Japanese traditions and the honor of warriors.

This conflict of values ultimately led to the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877, where Saigō led a rebellion against the modern, centrally managed army of the Meiji government. Although the rebellion initially had success, it was eventually suppressed, and Saigō was forced to retreat to Kagoshima. Surrounded and outnumbered, he faced inevitable defeat.

After his death, Saigō was posthumously rehabilitated by the Meiji government, and his status was elevated. His life and death have been depicted in literature and film many times, becoming a lasting symbol of Japan's dichotomy between tradition and modernization. Saigō Takamori remains not just an icon of samurai honor but also a reminder of Japan's complex journey through history.

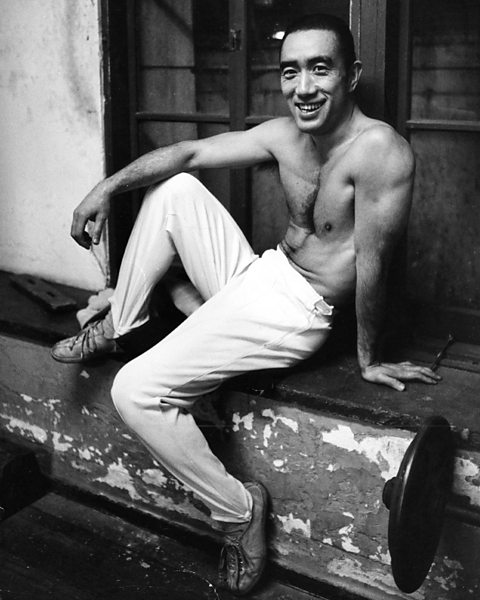

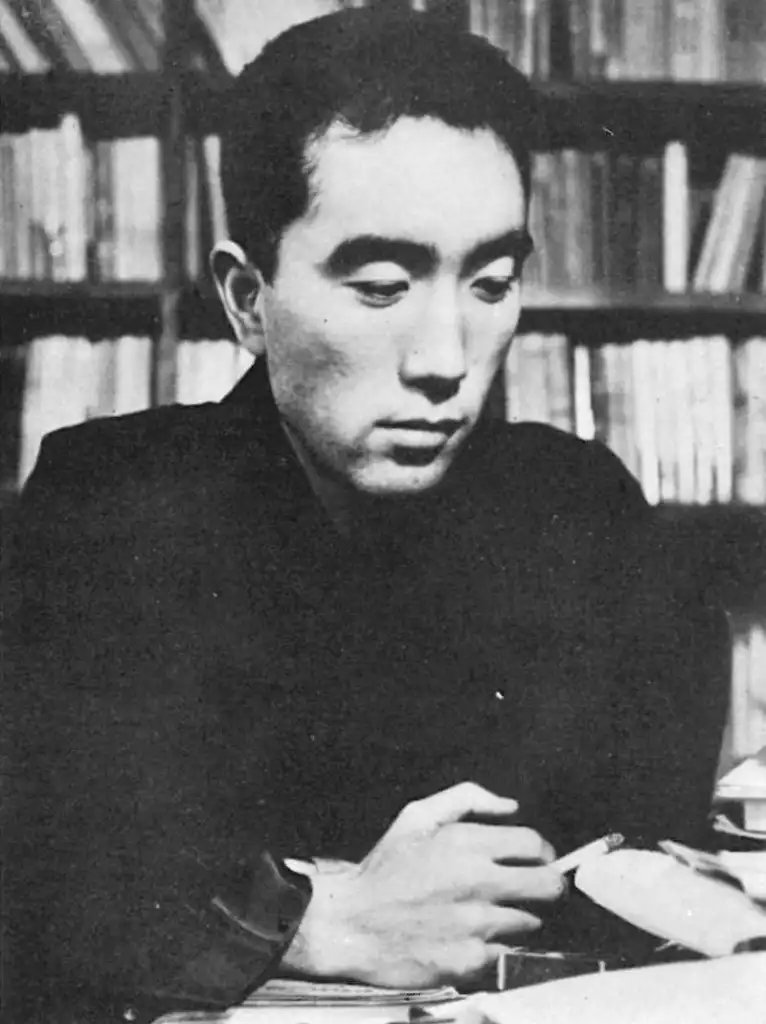

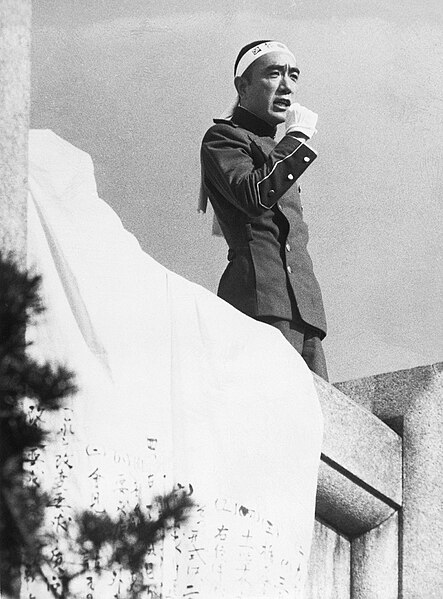

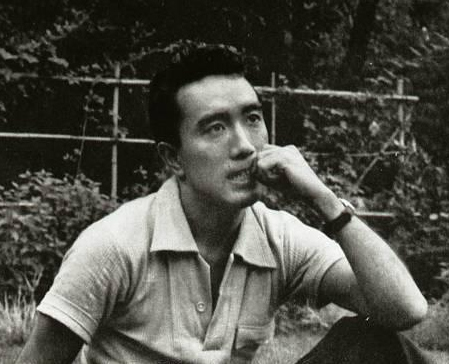

The Story of Yukio Mishima (1925-1970)

Mishima was born in Tokyo in 1925 and from an early age showed an extraordinary interest in literature and the history of Japan. His work was deeply rooted in Japanese aesthetics and philosophy, yet it was also marked by deep pessimism towards contemporaneity. Over the years, his fascination with the samurai tradition and bushidō deepened, reflected in his numerous literary works and public appearances.

On November 25, 1970, Mishima performed a dramatic and shocking act that would be etched in the annals of Japanese history. Along with four members of Tatenokai, he stormed the main Self-Defense Forces base in Tokyo, captured the base commander, and called upon the assembled soldiers to reject the contemporary government and return to imperial values. When his coup attempt failed, and his appeal was ignored, Mishima performed public seppuku in the traditional samurai style.

Harakiri in Modern Times

Suicide Statistics in Japan

Suicide Statistics in Japan

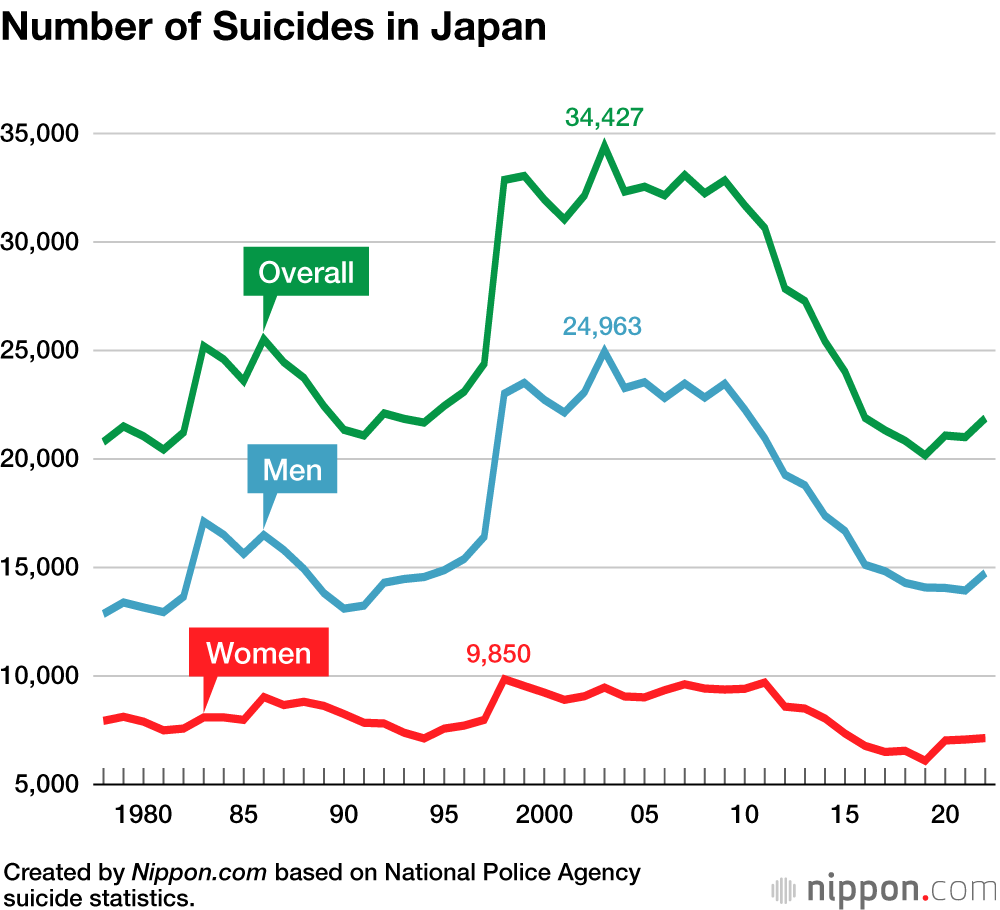

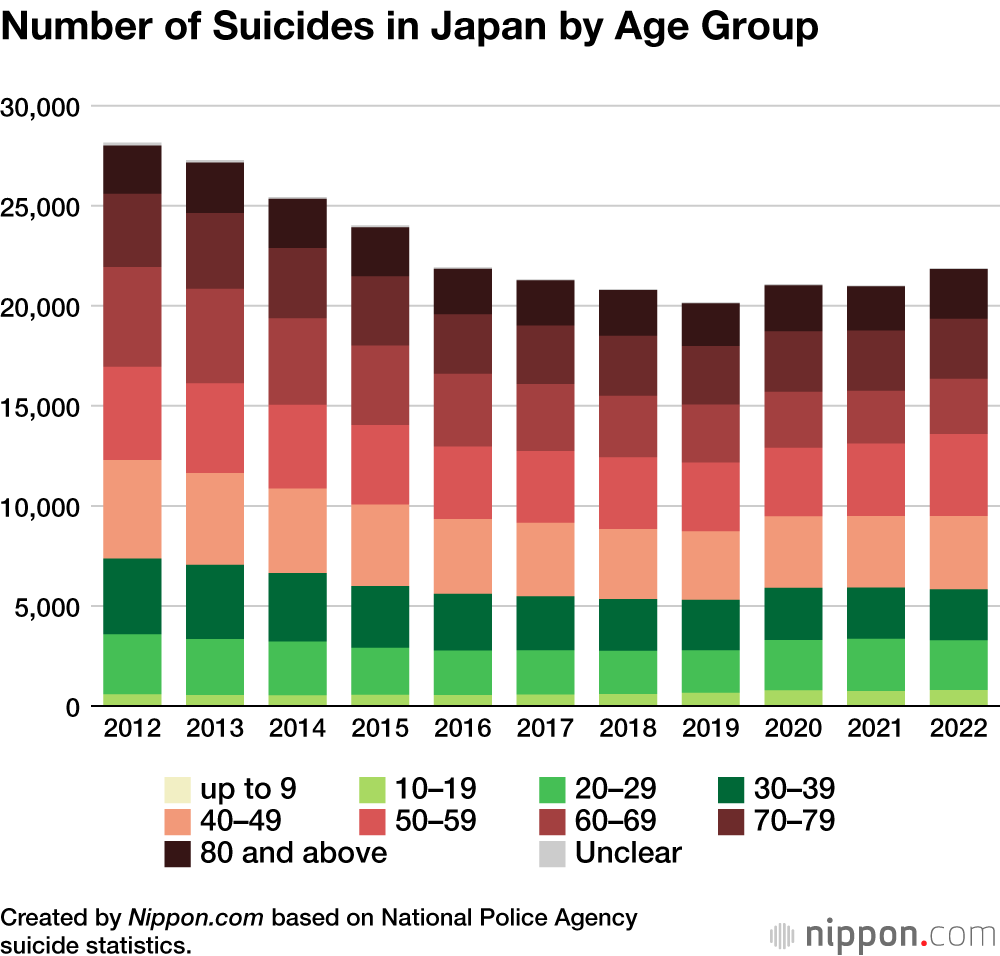

Japan has one of the highest suicide rates among developed countries. Although these rates have declined from their peak in 2003, when there were 34.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, they remain high. In 2020, the suicide rate was about 16.6 per 100,000, a significant drop, but still placing Japan at the forefront. Unlike historical harakiri, contemporary suicides are less often motivated by issues of honor, and more frequently by problems such as depression, occupational stress, or financial difficulties. Perhaps our interpretation of these acts is changing, rather than the acts themselves?

Harakiri Among Yakuza Members

Harakiri Among Yakuza Members

Among members of the yakuza, Japan’s traditional mafia, the idea of honorable suicide as a punishment for dishonor or failed missions has lasted longer than in the general population. Although there are no precise, official statistics on suicides among yakuza, reports indicate that these practices occur, though they are much rarer than in the past. Traditional harakiri has been replaced by more symbolic acts of penance, such as yubitsume, or finger-cutting, which is still practiced as a form of apology or penance. Nonetheless, reports of individual acts of hara-kiri committed by yakuza members do emerge from time to time.

Seppuku in Culture

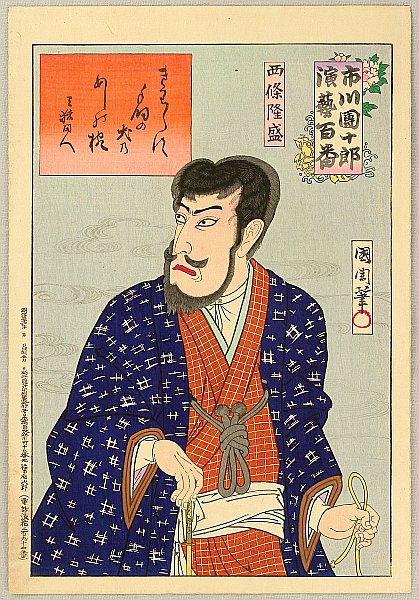

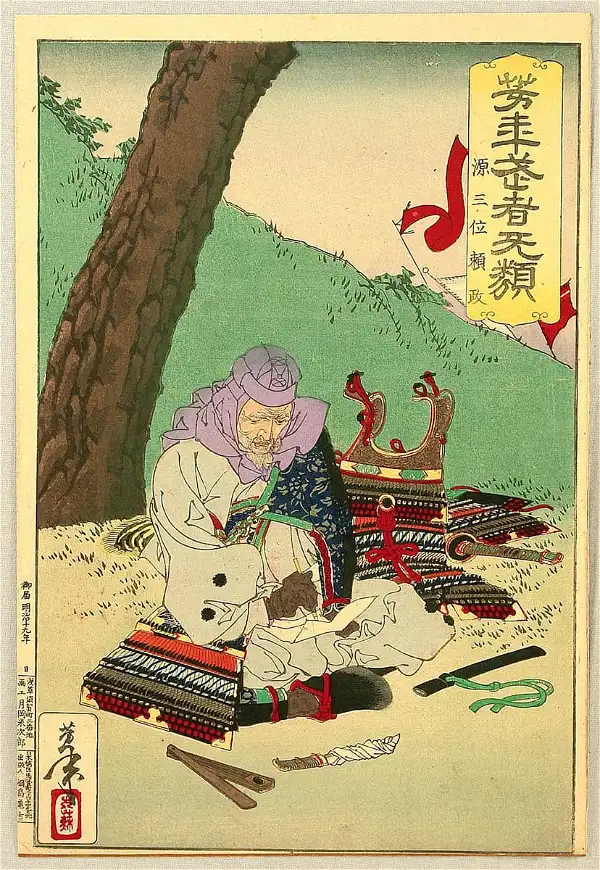

Ukiyo-e: "Samurai Committing Seppuku" (1790, Katsushika Hokusai)

One of the classic ukiyo-e prints by Katsushika Hokusai depicts a samurai performing seppuku. This work shows the lone figure of a warrior conducting the suicide ritual in full ceremony. The background of the image features subtly outlined mountains and a misty atmosphere, enhancing the drama of the scene. In this piece, seppuku is presented as an act of ultimate courage and honor, invoking the samurai code of bushidō, which dictates that death in defense of honor is the pinnacle of bravery and dignity.

Ukiyo-e: "The Last Stand of the Samurai" (1848, Utagawa Kuniyoshi)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, one of the great masters of ukiyo-e, created a series of prints dedicated to samurais, including the dramatic scene "The Last Stand of the Samurai". This graphic portrays a group of warriors preparing for collective seppuku after a lost battle. Kuniyoshi's work explores themes of loyalty, bravery, and tragic heroism, with seppuku being presented as the highest expression of these values, fitting into the context of samurai tradition and Japanese history.

Anime: "Rurouni Kenshin: Trust & Betrayal" (1999, Kazuhiro Furuhashi)

Anime: "Rurouni Kenshin: Trust & Betrayal" (1999, Kazuhiro Furuhashi)

In this four-episode OVA series, which is a prequel to the popular anime "Rurouni Kenshin", seppuku plays a significant role in the story of Kenshin Himura, a samurai who becomes a gentle wanderer after a brutal past as an assassin. One episode features a seppuku scene that serves as an emotional climax, emphasizing the consequences of Kenshin’s choices and the impact of samurai traditions on his life.

Anime: "Basilisk" (2005, Fuminori Kizaki)

"Basilisk" is an anime set in the brutal world of ninja warriors from two rival clans, Iga and Kouga, who are forced to fight to the death. In one episode, seppuku appears as an element of crime, where a character is forced to commit suicide. In "Basilisk", seppuku reveals the dark sides of feudal Japan, where honor and violence are inextricably linked.

Film: "Harakiri" (1962, Masaki Kobayashi)

Film: "Harakiri" (1962, Masaki Kobayashi)

This classic Japanese film criticizes samurai ideals of honor and seppuku. "Harakiri" tells the story of Hanshiro, a samurai who, in desperation and poverty, attempts to expose the hypocrisy of the samurai code of bushidō. Here, seppuku is not portrayed as an act of honor, but as a tool for social control and harm. It is a must-watch for anyone interested in understanding the ideas of Japanese seppuku and honor more broadly.

Film: "The Last Samurai" (2003, Edward Zwick)

In the Hollywood production "The Last Samurai", seppuku appears as a dramatic plot element influencing the main character, Captain Algren (played by Tom Cruise). The film depicts seppuku as an element of the honorable death of a samurai who loses in the struggle to preserve traditional values in the face of Japan’s modernization. This is a key moment, highlighting the cultural and personal conflicts of the characters.

Video Game: "Total War: Shogun 2" (2011, Creative Assembly)

Video Game: "Total War: Shogun 2" (2011, Creative Assembly)

In the strategic computer game "Total War: Shogun 2", players can manage samurai clans in feudal Japan. Seppuku appears here as an option for generals who have failed their shogun. This mechanic introduces historical and cultural elements to the game, enhancing the overall “atmosphere” of this iconic strategy classic.

"Ghost of Tsushima" is an action game set during the Mongol invasion of Japan in the 13th century. The game features seppuku scenes, which are presented as important ritual moments, emphasizing samurai honor and sacrifice. These moments are emotionally intense and serve as a deep commentary on themes of honor, loyalty, and sacrifice in the lives of samurais.

Conclusion

Although seppuku as a practice of socially acceptable and even lauded, sanctified suicide has mostly remained in the shadows of history, its resonance in the culture and consciousness of Japan is still evident.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES

The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

The Aokigahara Suicide Forest: What Secrets Do the Silent Trees Guard?

Sword Master and Wordsmith Miyamoto Musashi: Samurai, Artist, and Philosopher

Everything about the Samurai Katana - Structure, History, Customs, and Symbolism

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Harakiri (腹切り)

Harakiri (腹切り) The Hidden Meaning in the Order of the Kanji

The Hidden Meaning in the Order of the Kanji Organization

Organization

Variants of the Ritual Depending on the Performer's Status and Gender

Variants of the Ritual Depending on the Performer's Status and Gender

Why?

Why? Three People, Three Stories of Seppuku

Three People, Three Stories of Seppuku Suicide Statistics in Japan

Suicide Statistics in Japan Harakiri Among Yakuza Members

Harakiri Among Yakuza Members

Anime: "Rurouni Kenshin: Trust & Betrayal" (1999, Kazuhiro Furuhashi)

Anime: "Rurouni Kenshin: Trust & Betrayal" (1999, Kazuhiro Furuhashi) Film: "Harakiri" (1962, Masaki Kobayashi)

Film: "Harakiri" (1962, Masaki Kobayashi) Video Game: "Total War: Shogun 2" (2011, Creative Assembly)

Video Game: "Total War: Shogun 2" (2011, Creative Assembly)