What is the Yakuza? - Can One Be a Bloody Gangster, Honorable Samurai, Drug Baron, and Contemporary Robin Hood All in One?

Instroduction

YA '八' + KU '九' + ZA '三' = 5, 3, 9

YA '八' + KU '九' + ZA '三' = 5, 3, 9

The name 'Yakuza' originates from the Japanese card game 'Oicho-Kabu', similar to baccarat. The term 'yakuza' comes from the worst combination of cards: 'ya' (八), 'ku' (九), and 'za' (三), meaning eight, nine, and three respectively. The sum of these numbers is the least advantageous in the game, which led to the use of this term in the context of 'useless' or 'worthless' people. The metaphorical use of this term then transferred to individuals living on the social margins, including members of criminal gangs, leading to the modern meaning of 'Yakuza.'

Yakuza History

Edo (1603~1868)

Meiji and Taisho (1868 ~1926)

Meiji and Taisho (1868 ~1926)

The changes brought about by the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) and the following Taisho period (1912-1926) had a significant impact on the development of the Yakuza. Japan's modernization, opening to Western influences, and socio-economic transformations created new opportunities and challenges for the organization. During the Meiji era, with the introduction of a new legal and police system, Yakuza began organizing into more coordinated groups to survive increased government pressure. These changes led the Yakuza to engage more in legal and semi-legal businesses, especially in gambling and trade sectors. In the Taisho era, Japan experienced growth in urbanization and industrialization, which the Yakuza utilized by expanding their activities into new areas such as illegal gambling dens, brothels, and money exchange offices, responding to the growing demand in rapidly developing cities.

Showa Period (1926~1939)

Showa Period (1926~1939)

The Showa period, beginning in 1926, brought further challenges and opportunities for the Yakuza, especially in the 1930s as Japan increasingly immersed itself in militaristic and expansionist nationalism. The rise of nationalism and ultra-nationalist movements created a new arena for the Yakuza, which began to act as an unofficial force supporting government and military goals, often in secret operations or intimidating political opponents. This period also saw the development of the Yakuza's ties with politics and high-ranking state officials, providing it with protection and influence. At the same time, the Yakuza continued the development of its traditional criminal activities, such as gambling, prostitution, and extortion, adapting to the changing socio-economic conditions. In the 1930s, the Yakuza also began to engage more in international trade, including opium smuggling, contributing to further growth of its influence and operational scope.

World War II

World War II

During World War II, the Yakuza played a significant, though often hidden, role in Japanese society. Wartime conditions and nationwide mobilizations contributed to the further blurring of the line between legal and illegal activities, creating new opportunities for criminal organizations. The Yakuza, utilizing its organizational skills and extensive networks, engaged in various activities, from black market trading and distribution of scarce goods to collaborating with government agencies to maintain order and internal stability. Due to restrictions in supplies and resources, the Yakuza often controlled key resources for the wartime economy, such as food, fuel, and even medicines, using them for their own enrichment and to increase their influence.

Post-War Period

Post-War Period

After the end of World War II, Japan experienced a period of reconstruction and chaos, creating ideal conditions for the development of the Yakuza. During this time, the organization began to engage in the black market and other illegal activities to meet the growing demand for goods and services unavailable in the devastated economy. The Yakuza used its connections and resources to provide access to commodities, such as food, fuel, and medicines, significantly increasing its influence and reputation. This period also saw the crystallization of the Yakuza's ties with politics, especially with the conservative Liberal Democratic Party, further strengthening its influence in Japanese society.

Expansion (1960~70)

Expansion (1960~70)

In the 1960s and 70s, the Yakuza expanded its activities into more organized crime, including drug and arms trafficking. Yakuza groups also began investing in legitimate ventures, such as construction, real estate, and entertainment. These decades also saw international development, where the Yakuza began cooperating with other criminal organizations worldwide, including the Italian mafia and Chinese triads. This expansion solidified its position as a global player in the criminal world.

Internal Conflicts and Splits of the 1980s

Internal Conflicts and Splits of the 1980s

In the 1980s and 90s, internal conflicts and rivalry between different Yakuza factions began to escalate. One of the most significant conflicts was the so-called Yama-Ichi War of the 1980s, a bloody battle between two major factions of the Yamaguchi-gumi. This internal struggle led to hundreds of murders and retaliatory actions, drawing public and law enforcement attention to the Yakuza, leading to increased legal and police pressure on the organization.

New Challenges and Adaptation in the 21st Century

New Challenges and Adaptation in the 21st Century

In the 21st century, the Yakuza faces new challenges, including increased pressure from the Japanese government, which has introduced a series of measures aimed at curbing its activities. The Anti-Organized Crime Group Act, introduced in 1992, and subsequent amendments, have significantly hindered Yakuza operations, limiting its ability to conduct business and recruit new members. In response, many Yakuza groups have started exploring new methods of operation, including shifting some of their activities to cyberspace and engaging in more sophisticated forms of economic crime.

Who 'Founded' the Yakuza?

Who 'Founded' the Yakuza?

The early history of the Yakuza, covering the Edo, Meiji, and Taisho periods, is not associated with one dominating figure who could be considered the most important. Due to the nature and structure of the Yakuza as a decentralized and loosely organized federation of various groups, it is difficult to pinpoint a single individual leader who had a key impact on the entire organization in its early years. However, among the figures who played a significant role in shaping the early Yakuza, Banzuiin Chōbei is often mentioned.

Banzuiin Chōbei - The Beginnings

Banzuiin Chōbei - The Beginnings

Banzuiin Chōbei was a notable figure in Edo (former Tokyo) in the 17th century. Considered one of the first "godfathers" of the Yakuza, he led a group of machi-yakko (literally "servants of the town"), which acted as a kind of local defense against crime. His actions were characterized by protecting ordinary people from violence and exploitation by bandits or corrupt samurais. In this way, Chōbei gained recognition and respect among the local community, contributing to the image of the Yakuza as an organization rooted in the defense of local communities.

Chōbei's Power and Influence

Chōbei was known for his authority and ability to maintain order in his area of influence. His leadership of the machi-yakko was not just about strength but also involved negotiation skills and conflict management. Although his actions could be seen as crime protection, they also fell into a legal gray area. Banzuiin Chōbei and his group commanded both respect and fear, laying the foundation for the later image of the Yakuza as an organization balancing between legal and illegal activities.

Chōbei's Legacy

Chōbei's Legacy

Although Banzuiin Chōbei was not a member of the Yakuza in today's understanding of the term, his actions and stance significantly influenced the formation of the culture and practices associated with this organization. His figure remains present in Japanese culture, often recalled as an example of an honorable criminal who placed the welfare of the community above personal interests. Chōbei's legacy, as a leader of a group on the edge of the law, influenced the formation of the idea of the Yakuza as an organization that, besides criminal activity, also carried a kind of honor code and principles.

Yakuza – Range of Activities

Organized Crime

Organized Crime

The Yakuza, known as one of the most complex and branched criminal organizations in the world, engages in a wide range of criminal activities. From traditional gambling, extortion, and drug trafficking to more organized forms of crime such as human trafficking and international smuggling. Yakuza groups also operate in prostitution, managing networks of brothels and escort agencies in and outside of Japan. Their activities also extend to financial crime, including fraud, money laundering, and other types of corporate scams.

Real Estate

Real Estate

The Yakuza has long been involved in the real estate market, using intimidation and violence tactics to acquire land and properties. This form of operation often includes "sōkaiya" - gangsters specializing in corporate manipulation and blackmailing companies. Sōkaiya use their shares in companies to influence corporate decisions and to extort money from businesses in exchange for protection against other gangsters or scandals. Additionally, the Yakuza is known for engaging in "jigeya" procedures, involving forcing residents to leave their homes to facilitate property development.

Legal Activities

Legal Activities

Despite their criminal operations, the Yakuza also maintains a presence in legitimate business, often serving as a front for their illegal operations. Enterprises run by or with the involvement of the Yakuza include restaurants, bars, nightclubs, construction companies, and others. Some of these businesses operate fully legally, though they may be used for money laundering or other illegal activities. Furthermore, the Yakuza invests in legal financial markets, real estate, and other economic sectors, allowing it to diversify income sources and increase its economic power.

Attempts at Legitimization

Attempts at Legitimization

Attempts to legalize and legitimize Yakuza activities have become more visible in recent decades. The organization tries to portray itself in media and society as a "chivalrous organization" ("ninkyō dantai"), which it has somewhat achieved through public charitable actions and assistance during natural disasters. However, despite these actions, the Yakuza remains under strict legal and social scrutiny, and its activities are the subject of numerous debates and controversies in Japan. This ambiguity - presence in legal business and criminal underworld - is a key element of the complex image of the Yakuza in Japanese society.

Yakuza as a Charitable Organization?

How is the Yakuza structured?

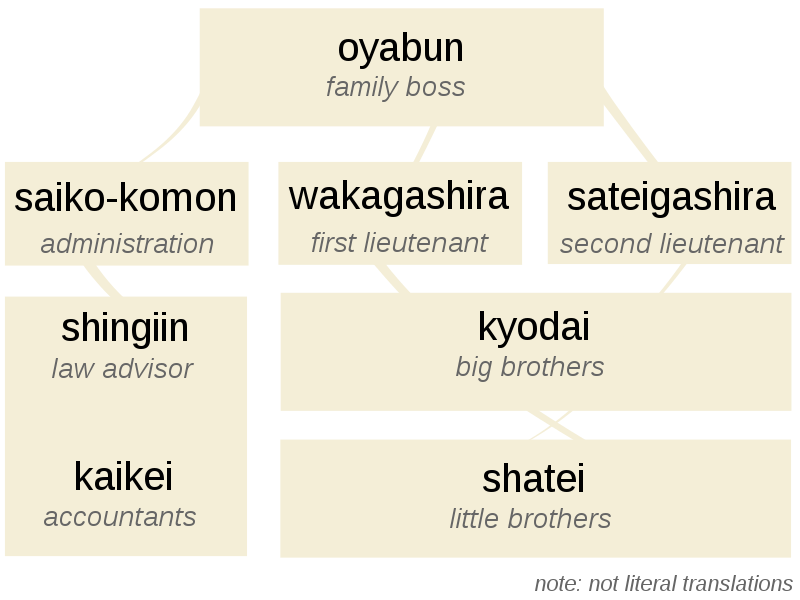

General Structure

Clans and Families

Clans and Families

The Yakuza is divided into many clans, also known as "gumi" or "families." The most well-known clans are Yamaguchi-gumi, Inagawa-kai, and Sumiyoshi-kai, each with its network of connections and activities. These clans may contain smaller groups, known as "bōryokudan" (violence groups), which operate locally. Within these groups are even smaller units, known as "kobun" (children), who are the direct subordinates of their oyabuns. This structure allows for effective management and coordination of activities throughout Japan and facilitates the spread of the Yakuza's influence beyond the country's borders.

Major Yakuza Traditions

Yubitsume (指詰め, "shortening fingers") - The Ritual of Finger Cutting

Yubitsume (指詰め, "shortening fingers") - The Ritual of Finger Cutting

Yubitsume is a self-punishment ritual involving the amputation of a finger joint. This practice is an expression of apology for errors or offenses against the organization. The loss of a finger also symbolizes the weakening of the samurai sword grip, increasing the Yakuza member's dependence on their oyabun (leader).

Sakazukigoto (盃事, "cup affair") - Yakuza Initiation Ceremony

Sakazukigoto (盃事, "cup affair") - Yakuza Initiation Ceremony

Sakazukigoto is a ceremony where a new member officially joins the Yakuza by exchanging sake cups with the oyabun. This ritual symbolizes the establishment of a familial bond between the oyabun and his subordinate (kobun) and a commitment to loyalty and obedience.

Oyabun-Kobun (親分子分, "parent-child") - Hierarchical Relationship

The Oyabun-Kobun system is based on hierarchy and loyalty, resembling a parent-child relationship. Members of lower ranks are obligated to obey and be loyal to their immediate superiors, ensuring discipline and structure in the organization. This structure reflects traditional Japanese family and social values.

Yakuza: Adaptation and Transformation

>>CHECK SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Enduring Legacy of the Bushido Code and Modern Samurai Clans

Bloody 'Ichi the Killer' - Japanese Cinema in its Most Extreme Form

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

YA '八' + KU '九' + ZA '三' = 5, 3, 9

YA '八' + KU '九' + ZA '三' = 5, 3, 9 Meiji and Taisho (1868 ~1926)

Meiji and Taisho (1868 ~1926) Showa Period (1926~1939)

Showa Period (1926~1939) World War II

World War II Post-War Period

Post-War Period Expansion (1960~70)

Expansion (1960~70) Internal Conflicts and Splits of the 1980s

Internal Conflicts and Splits of the 1980s New Challenges and Adaptation in the 21st Century

New Challenges and Adaptation in the 21st Century Who 'Founded' the Yakuza?

Who 'Founded' the Yakuza? Banzuiin Chōbei - The Beginnings

Banzuiin Chōbei - The Beginnings Chōbei's Legacy

Chōbei's Legacy Organized Crime

Organized Crime Real Estate

Real Estate Legal Activities

Legal Activities Attempts at Legitimization

Attempts at Legitimization Clans and Families

Clans and Families Yubitsume (指詰め, "shortening fingers") - The Ritual of Finger Cutting

Yubitsume (指詰め, "shortening fingers") - The Ritual of Finger Cutting  Sakazukigoto (盃事, "cup affair") - Yakuza Initiation Ceremony

Sakazukigoto (盃事, "cup affair") - Yakuza Initiation Ceremony