Samurai War Banners: Japanese Heraldry Under Which Battles Were Fought

Flags and Banners We Know Well

In the following sections of this article, we’ll delve deeper into this unique tradition. We’ll explore how samurai designed their banners, the stories behind the most intriguing sashimono, and the symbolism attributed to various designs. Prepare for a captivating journey through the colorful aesthetics and strategies of Japan’s historical battlefields!

The History of Japanese Military Heraldry

The Beginnings: The Genpei War (1180–1185)

At the time, these flags were not yet part of a complex heraldic system. Instead, they often bore prayers to the war deity Hachiman (八幡). Believing in divine support, samurai inscribed requests for protection and victory on their flags. These were more religious artifacts than military markers, reflecting both the spiritual and practical needs of the era.

The flags were simple in construction: a long pole with a horizontal crossbar at the top, from which a narrow piece of fabric hung. Many can still be seen in illustrations from the Genpei period, such as depictions of the famous Battle of Kurikara, where red and white banners fluttered in the wind, clearly delineating the opposing sides.

The Development of Individual Heraldry: The Mongol Invasions (1274, 1281)

A turning point in Japanese heraldry came during the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. While the Japanese ultimately triumphed thanks to adverse weather conditions and the determination of their defenders, these conflicts had a profound impact on the development of their military identification system. For the first time, flags featuring family crests, known as mon, were used to distinguish individual commanders on the battlefield.

The battles with the Mongols required greater organization and clearer identification of units. It was during this time that the first flags with crests appeared, serving as command markers and evidence of participation in battle—especially important when commanders sought rewards for their contributions. For example, illustrations of the naval Battle of Hakata show the early use of individual flags on samurai boats.

These early crests, while still simple, began to reflect the status and identity of their owners. Samurai, eager to stand out and gain recognition, introduced increasingly unique designs, often inspired by nature or religion.

The Fall of the Ashikaga Shogunate: The Birth of Rich Symbolism

Newly established clans often adopted the crests of old families to bolster their legitimacy. This was the case with the Odawara Hōjō clan, which adopted the symbol of the old Hōjō family—three lozenges—to emphasize their heritage and claims to power. During this time, mon evolved toward more artistic and unique forms, often combining elements of nature, geometry, and religion (see the description of 15 mon of the most powerful samurai families: kamon).

Sengoku Jidai (15th–16th Centuries): Increasingly Complex Heraldry

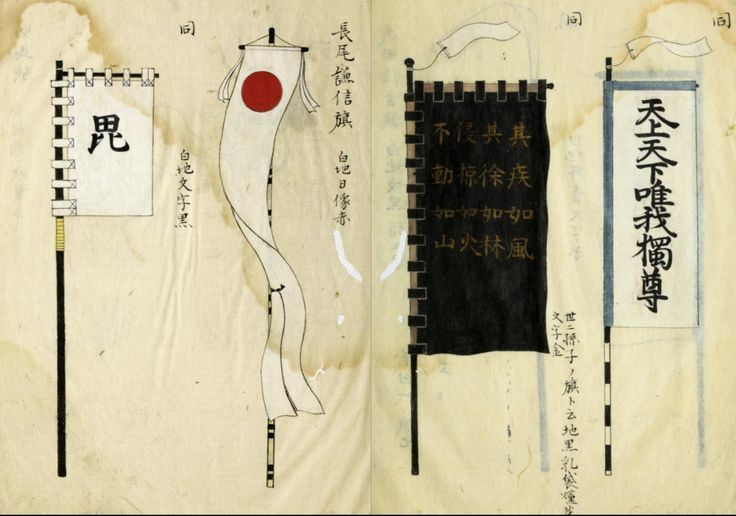

During this period, new types of flags and banners emerged, such as nobori—tall, rectangular banners identifying units—and uma-jirushi, insignias for mounted commanders. Nobori were often adorned with family crests (mon), battle slogans, or geometric patterns. In one of the most famous examples, Takeda Shingen used a banner with the phrase "Wind, Forest, Fire, Mountain" (Fūrinkazan), referring to military strategy principles described in Sun Tzu's Art of War.

Types of Banners and Flags on Samurai Battlefields

Hata-jirushi (旗印): Simple Battle Standards

Hata-jirushi remained a tool of identification for centuries, evolving into more advanced flags like nobori. The simple designs on hata-jirushi, such as vertical stripes or single symbols, inspired the more complex patterns that followed.

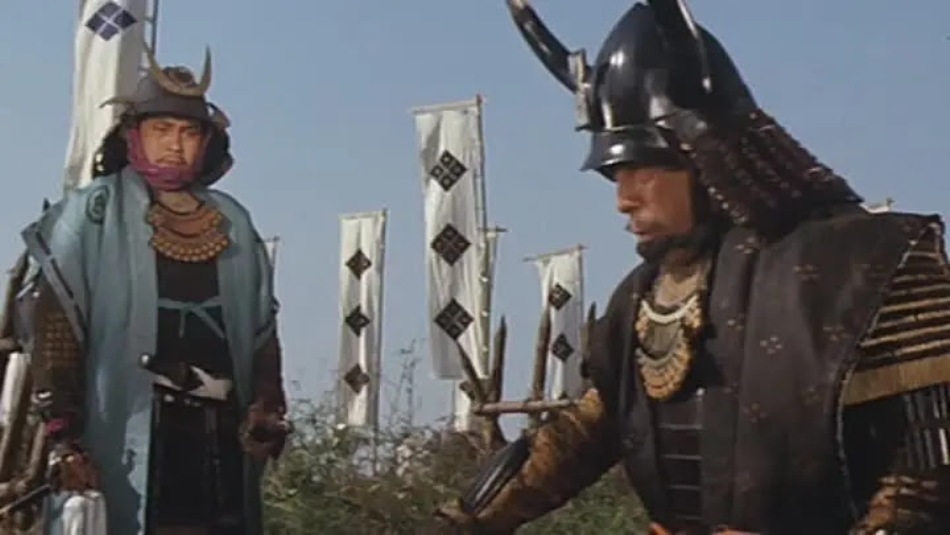

Nobori (幟): Tall and Sturdy Flags

Nobori were used to identify larger units, such as divisions or entire armies under specific daimyō. Each flag could feature a family crest (mon), a battle slogan, or geometric patterns. They were often painted in distinct colors for different units, helping commanders manage their forces amidst the chaos of battle.

In military strategy, nobori functioned similarly to modern standards, and in large armies, all flags were gathered at the command center to monitor the battle's progress.

Sashimono (指物): Individual Warrior Flags

Sashimono (指物): Individual Warrior Flags

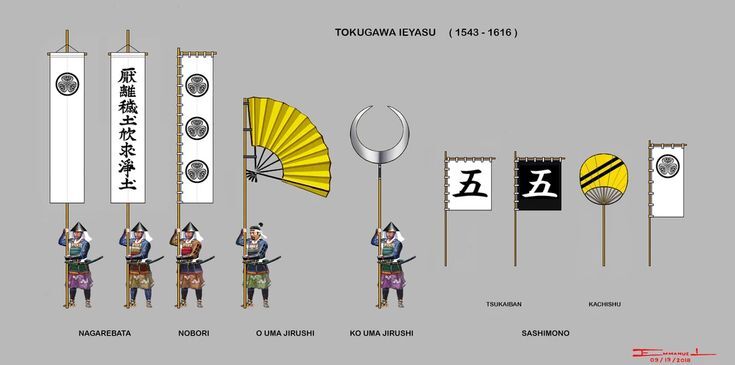

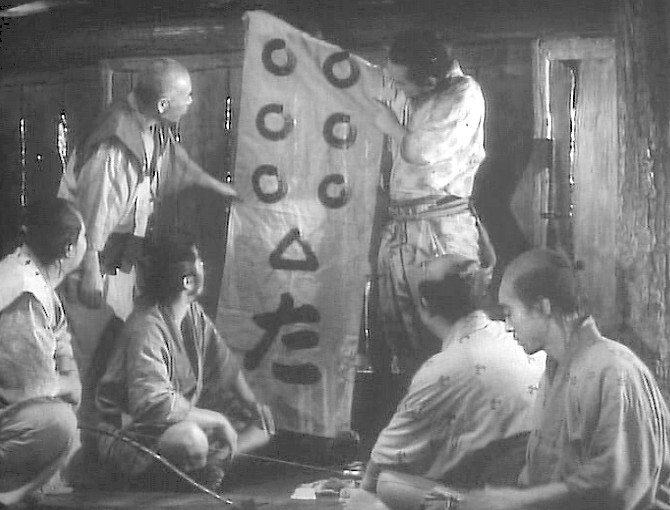

Sashimono were smaller than nobori and designed to be worn on the backs of individual soldiers, such as ashigaru (infantry) or samurai. Attached to special mounts on their armor, these banners served as a kind of “uniform” for the army, enabling quick identification of allies in the heat of battle. Typical sashimono were rectangular in shape and made of lightweight fabric, making them practical, though their designs varied greatly.

The diversity of sashimono was immense. Simple designs with family crests (mon) appeared alongside more intricate creations featuring slogans, geometric patterns, or personal symbols. For example, in Tokugawa's army, soldiers often carried sashimono bearing numbers like "5" instead of the Tokugawa family crest, reflecting hierarchy and unit divisions.

Some sashimono were true works of art—embellished with gold or embroidery, they could signify the elite status of a unit or the individual rank of a warrior.

Uma-jirushi (馬印): Commander Insignia

Examples of uma-jirushi are spectacular: Tokugawa Ieyasu used a golden fan, Toyotomi Hideyoshi a giant golden gourd, and Takeda Shingen had a banner with the inscription “Fūrinkazan.” These symbols were often three-dimensional (not just drawings on a surface but physical objects) such as golden figures, umbrellas, or bells, making them visible from a great distance. Uma-jirushi served both practical and symbolic purposes—the presence of such insignia signified that the commander was there, which could inspire troops and intimidate enemies.

Horo (母衣): Balloon-like Protective Cloaks

Horo (母衣): Balloon-like Protective Cloaks

Initially simple cloaks, horo evolved into a unique element of heraldry. These special garments, resembling a balloon, were worn by elite units such as couriers (tsukaiban) and bodyguards who needed to be easily recognizable on the battlefield. Due to their construction, horo could somewhat protect against arrows from behind, although their primary purpose was visibility on the battlefield.

Horo were often decorated with family crests or unique patterns that distinguished them from the rest of the army. For instance, couriers in Takeda Shingen’s army wore horo with a centipede motif, symbolizing speed and tenacity.

Sode and Kasa-jirushi: Small Individual Markings

Sode and Kasa-jirushi: Small Individual Markings

Sode-jirushi (markings on shoulder guards) and kasa-jirushi (markings on helmets) were small accessories with similar functions to sashimono but were more subtle. Usually, these were small pieces of fabric or paper attached to the armor, bearing a simple inscription or symbol. They were mainly used by lower-ranking soldiers who could not afford more elaborate insignia.

Nagarebata (流れ旗): Flowing Streamers

Nagarebata were a type of flag resembling hata-jirushi but more elaborate. These long, narrow flags were attached to a horizontal bar and fluttered freely in the wind. Their name literally means “flowing flags.” They were often used during the Genpei Wars and by some armies in later eras as an alternative to nobori. They could be adorned with prayers, symbols of deities, or simple geometric patterns. In many cases, they served as ceremonial banners in military camps.

Jata (蛇旗): Flags with Dragons and Serpents

Jata were unique flags used by some armies, especially by warriors inspired by mythology and the symbolism of protective deities. These flags often depicted dragons, snakes, or other mythical creatures symbolizing strength and divine protection. For example, the banners featuring tigers and dragons used by the Uesugi clan emphasized their connection to Bishamonten, the god of war.

Tachi-hata (立旗): Vertical Camp Flags

Tachi-hata were vertical banners set up in military camps to designate specific sections such as headquarters, courier stations, or supply areas. Unlike nobori or sashimono, they were not carried during battles but served as organizational markers within the war camp.

Use on the Battlefield

Army Organization

Army Organization

On feudal Japanese battlefields, flags were more than just decorations—they were essential tools for organization and communication. In the chaos of battles involving tens of thousands of soldiers, visual signals were indispensable for identifying units, conveying orders, and maintaining order. Flags allowed commanders to quickly locate their units and monitor the progress of the fight.

Sashimono, worn on the backs of individual soldiers, acted as a kind of “uniform,” allowing quick identification of friend versus foe. For example, in the battles of Kawanakajima (1553–1564), the armies of Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin used sashimono with simple but distinctive designs: white crests on black or red backgrounds dominated Takeda’s forces, while Uesugi employed symbols such as the red sun of Bishamonten on a white background.

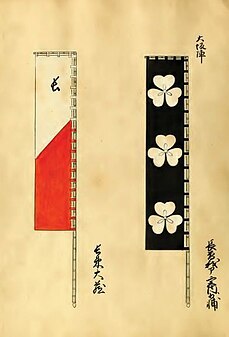

Larger flags like nobori were used to identify entire units. Each unit commander had their own set of flags indicating their position. In the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), Tokugawa Ieyasu’s forces carried white nobori with his crest—three hollyhock leaves (mitsuba aoi). In contrast, Ishida Mitsunari’s forces were marked with black and red nobori bearing his personal crests, making it easy to distinguish the opposing sides.

Messengers, Signalers, and Commanders

Messengers, Signalers, and Commanders

Flags were also used by couriers like tsukaiban, who wore visible horo—balloon-like cloaks that served both protective and identification purposes. These couriers were easily recognizable, enabling the rapid delivery of orders between commanders and units. For instance, Oda Nobunaga’s army at the Battle of Nagashino (1575) used a well-organized network of tsukaiban to coordinate the firepower of archers and teppō (musketeers with Portuguese arquebuses) against Takeda’s cavalry.

Daimyō and their commanders used uma-jirushi to mark their presence. These unique insignia, like Tokugawa’s golden fan or Hideyoshi’s gourd, served as mobile standards that helped organize the army while adding prestige to their owners. Uma-jirushi were heavily guarded by select samurai—losing them on the battlefield could spell disaster for the army’s morale.

Etiquette

Etiquette

Flags, especially uma-jirushi, were treated with near-sacred respect. They were never displayed without the physical presence of their owner—such an action could be seen as falsifying authority or attempting to deceive. For example, in the battles of Kawanakajima, Takeda Shingen personally ensured that his “Wind, Forest, Fire, Mountain” (Fūrinkazan) banner always accompanied him on the battlefield, inspiring his troops and underscoring his strategy based on Sun Tzu’s principles. Seeing this flag assured his soldiers that their leader was among them, fighting alongside them against their enemies.

Etiquette also extended to the use of flags in military camps. Nobori and hata-jirushi were placed at command posts to clearly mark generals’ quarters. For instance, in Ishida Mitsunari’s camp during Sekigahara, black flags bearing his crest adorned the main command site, while others marked different sections such as supply depots or field hospitals.

Symbolism and Meaning of Flags

Clan Crests (Mon): Family Identity

Clan Crests (Mon): Family Identity

Mons (紋), or family crests, were among the most important symbolic elements of flags used on feudal Japanese battlefields. These simple yet striking symbols were visual expressions of identity and clan pride. Mons often featured geometric patterns, plant or animal motifs, and reflected the values, traditions, or legends associated with a family. For example (more examples here: Kamon of 15 Strongest Samurai Clans of Japan):

♦ The Tokugawa clan used the symbol of three hollyhock leaves (三葉葵, mitsu-aoi), representing their lineage and later becoming one of the most recognizable crests in Japan.

♦ The Takeda clan employed the simple yet powerful symbol of four diamonds (四つ菱, yotsu-bishi), symbolizing stability and unity.

Mons were displayed on sashimono (small banners carried by soldiers), nobori (tall unit standards), and uma-jirushi (commanders’ insignias), creating a cohesive identification system on the battlefield. Their simplicity was essential as they needed to be recognizable from great distances, even amidst the chaos of battle.

Slogans and Mottos: Battlefield Motivation

Some samurai flags, instead of displaying mons, were adorned with slogans or mottos designed to inspire soldiers and convey the commander’s spirit, philosophy, or values. These short, impactful phrases were not only practical tools on the battlefield but also expressions of the leader’s identity and ambition. These slogans often had religious or moral undertones, reminding soldiers of their mission and duty (more about these mottos can be found here: 10 Japanese Proverbs – Inspirations and Lessons Hidden in Ages-Old Characters). Examples include:

▫ “Tenka Fubu” (天下布武) – “Unify the nation under martial rule”

▫ “Tenka Fubu” (天下布武) – “Unify the nation under martial rule”

This famous motto of Oda Nobunaga expressed his ambition to conquer all of Japan and establish stability under his rule. Displayed on his flags, it became synonymous with his political and military vision.

▫ “Nana korobi ya oki” (七転び八起き) – “Fall seven times, rise eight”

A symbol of perseverance and resilience, used by some commanders to motivate their troops to fight despite the odds. Flags bearing this slogan were often seen in the armies of smaller but determined clans.

▫ “Buun Chōkyū” (武運長久) – “May martial fortunes last forever”

This popular war blessing, featured on flags of daimyō like Tokugawa Ieyasu, expressed the wish for lasting military success and luck in battle. A chillingly pragmatic sentiment.

▫ “Ichigo Ichie” (一期一会) – “One encounter, one opportunity”

A philosophical slogan reminding warriors that every moment is unique and unrepeatable, and that a battle is a singular event to be fully embraced. It was used by commanders who valued both bravery and wisdom in their troops.

▫ “Makoto” (誠) – “Sincerity” or “Loyalty”

This unequivocal motto often appeared on the flags of warriors adhering to the bushidō code. For instance, the Aizu clan, known for their unwavering loyalty to their lords, used this word as a reminder of the fundamental values of the samurai.

▫ Katō Kiyomasa, a devout follower of Nichiren Buddhism, used flags bearing mantras to bolster the spirit of his soldiers.

▫ The Shimazu clan employed the motto “Family unity is strength” (家中一心, kachū isshin), emphasizing the value of loyalty within their army.

Each of these slogans not only motivated soldiers but also communicated the ideology of the commander and the values they sought to instill in their troops and descendants. Flag slogans became symbols of their owners’ identities, reflecting their strategy, faith, and ambitions.

Colors and Unit Identification

► In Takeda Shingen’s army, different units used nobori bearing the clan’s crest but on varying backgrounds, such as red, black, and white, to differentiate specific sections.

► During the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), Tokugawa Ieyasu’s army was uniformly marked with white flags, giving it a cohesive and organized appearance. In contrast, Ishida Mitsunari’s army used a more varied palette, reflecting the diversity of his allies.

► The Sanada clan, renowned for their guerrilla tactics, used red flags with six coins (六文銭, rokumonsen), symbolizing the toll for crossing into the afterlife—both an inspiration and a warning to their enemies.

Colors also carried symbolic meanings. Red symbolized courage and strength; it was popular among warrior clans like Takeda and Sanada. White denoted purity and loyalty; it was frequently used by clans such as Tokugawa. Black represented power and solemnity; it was often used in ceremonial flags.

Rituals and Customs Related to Banners

Banners were regarded as objects of great spiritual and symbolic value, and their consecration was believed to boost troop morale and secure divine favor. These practices reflected the samurai’s deep faith in spiritual support during battle.

In some cases, banners held ritual significance—they were offered to temples as votive thanks for victories or preserved as relics in shrines dedicated to the spirits of fallen warriors. In such places, historical banners remain visible today, serving as reminders of feudal Japan’s history.

Samurai Flags Today

The world of video games and historical reenactments also draws heavily on the legacy of samurai heraldry. In games such as Total War: Shogun 2 or Ghost of Tsushima, banners are key to building atmosphere and realism. During historical battle reenactments in Japan, such as the Shingen-Ko Festival in Kōfu, the sight of marching troops with sashimono on their backs and nobori fluttering in the wind brings history to life for contemporary audiences.

The influence of historical flags is also evident in art and aesthetics. Modern paintings and graphics often reference the simple yet evocative designs of mons and slogans. Both traditional Japanese art and modern design draw inspiration from the geometric layouts, harmonious compositions, and symbolism used in samurai banners.

The legacy of samurai banners is not merely a relic of the past—it lives on in contemporary culture and art, reminding us of Japan’s rich history, its warriors, and the values they conveyed through these extraordinary symbols.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Samurai and His Falcon – The Noble Tradition of Takagari Hunting

Shiba Inu – A Companion of Medieval Samurai and a Star of the Internet

10 Facts About Samurai That Are Often Misunderstood: Let's Discover the Real Person Behind the Armor

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Sashimono (指物): Individual Warrior Flags

Sashimono (指物): Individual Warrior Flags Horo (母衣): Balloon-like Protective Cloaks

Horo (母衣): Balloon-like Protective Cloaks Sode and Kasa-jirushi: Small Individual Markings

Sode and Kasa-jirushi: Small Individual Markings

Army Organization

Army Organization

Messengers, Signalers, and Commanders

Messengers, Signalers, and Commanders Etiquette

Etiquette Clan Crests (Mon): Family Identity

Clan Crests (Mon): Family Identity ▫ “Tenka Fubu” (天下布武) – “Unify the nation under martial rule”

▫ “Tenka Fubu” (天下布武) – “Unify the nation under martial rule”