The Etiquette of Samurai Weaponry – When the Steel of the Katana and a Subtle Gesture Spoke in Silence

Nine Centimeters from Death

In this article, we will enter the world in which the blade was the soul, and every gesture surrounding it—a manifestation of a clan’s honor, the warrior’s status, and the intentions of an encounter. We will speak of the ways the sword—tachi and katana—was worn throughout various eras, how it was handed over, removed, placed, how its position in space spoke before any words were uttered. We will show why offering an unsheathed blade could be the ultimate expression of trust, and how touching the blade with bare hands could be an unforgivable breach of etiquette. This is a story of the art of presence with a weapon, of a language without words, of a world in which a warrior’s core virtue was silence—so he spoke through his sword.

The Sword Defines the Warrior

刀は武士の魂なり

Katana wa bushi no tamashii nari

“The katana is the soul of the samurai.”

From childhood, the warrior was taught that the blade was not only for cutting—it spoke, instructed, warned, and punished. When a samurai looked at the polished blade, he saw not just steel and temper—he saw himself. And when he passed it on, he passed on a part of his soul.

In the society of feudal Japan, where everything had its ritual and place, the sword was also a symbol of authority and social identity. In the Edo period, when weapon-wearing was regulated by bakufu edicts (more on the structure of society in that era here: What to Do with a Society of Samurai Who Only Know War and Death in Times of Peace? - The Clever Ideas of the Tokugawa Shoguns), only samurai had the right to wear daishō—a pair of swords: the longer katana and the shorter wakizashi (for more on the types and history of the katana, see here: Discover the Katana – The Birth, Maturity, Wartime Life, and Noble Old Age of the Samurai Sword). This was not merely a matter of armament—it was status, visible from afar. The sword said: this man has privileges, but also duties. He has the right to carry arms, but also the obligation to know the rules of their use. Violating those rules could mean disgrace—or death. A samurai’s rank dictated not only what kind of weapon he could carry, but also how and where it was worn, how it was laid down, and how one bowed with it at one’s side.

The right to wear the daishō (the pair of katana and wakizashi) was not universal. It was reserved solely for the warrior class. Merchants, peasants, and artisans could not even dream of owning a katana—except in rare cases as a family heirloom, but never worn at the waist. Even rōnin—masterless samurai—became a problem for the bakufu, for they had the right to carry swords but lacked a defined role in society. Thus, there were attempts to reduce their numbers or force them to renounce their status, which meant losing the privilege of bearing arms and having to bow to anyone who did possess a sword. The katana, then, was not only a weapon—it was a passport of class, a symbol of loyalty to one’s lord and state, and a calling card of the soul, upon which one could judge a samurai even before he spoke.

How to Wear a Katana

At the Belt (obi 帯) – Wearing the katana and tachi in Different Eras

During the Sengoku period, the tachi (太刀) prevailed—a longer, more curved sword worn with the edge facing downward, suspended from special leather straps (ashi 足 – “legs”) attached to the armor belt. The tachi was ideal for mounted combat—its draw from the saddle was smooth and swift.

Over time, especially in the Azuchi-Momoyama period, the uchigatana (打刀)—a form of the katana—became more popular. The katana was worn tucked into the obi belt, on the left side of the body, always with the edge facing upward. This configuration allowed for a quick draw with the right hand and a cut in a single, fluid motion—a technique known as nukitsuke (抜き付け), which is the foundation of sword arts such as iaido.

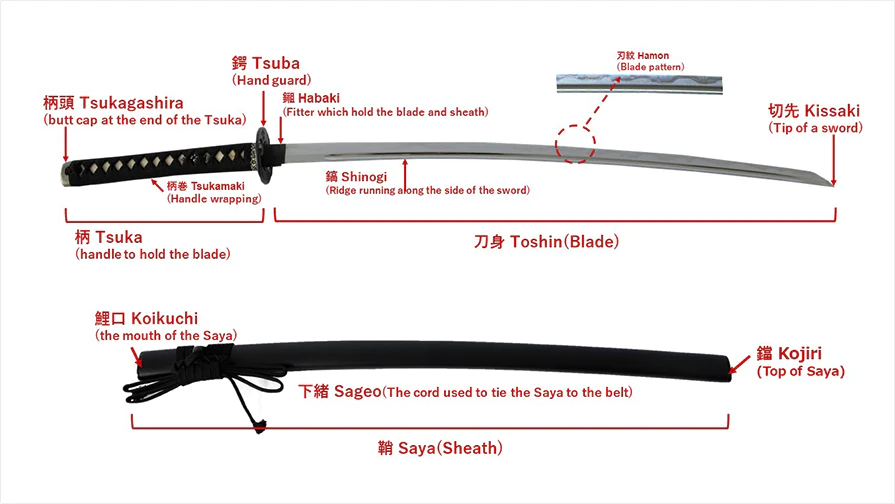

It is worth noting that the sword was placed in the obi without a shoulder strap or any fasteners—it was held solely by the tension of the fabric. Sometimes an additional element played a role: the sageo (下緒 – “hanging cord”)—a decorative but also functional cord that secured the scabbard (saya) to the obi belt.

□ Left Side of the Body, Blade Facing Up

But there was also a third layer: this arrangement said, “I am ready, but I do not seek a fight.” The positioning of the sword was a legible message.

□ The Angle of Wear and Social Status

Lower-ranking samurai, foot soldiers, or retainers, on the other hand, kept their katanas closer to the body, almost vertically, with the saya parallel to the leg. This was a gesture of humility and modesty, but also of caution—the less space around oneself, the less opportunity for conflict.

This seemingly trivial detail held great significance—just like the manner of moving with the weapon. A dragging sword signified carelessness or provocation.

□ Saya-ate (鞘当て) – Accidental Contact of Scabbards as an Insult

In the crowded alleys of Edo or Kyoto, it sometimes happened that the scabbards of two passing warriors would accidentally brush against each other. But in this world, “accident” did not exist. This event had a name: saya-ate (鞘当て – “scabbard strike”).

Touching someone else’s saya could be perceived as a provocation or insult, or even as a challenge to a duel. In a culture where every gesture carried meaning, one had to move with skill while armed, holding the hilt raised and the saya close to the body. Many master swordsmen could interpret such an encounter in an instant—whether it was deliberate, accidental, or worth responding to—and that sometimes determined life or death.

□ Koiguchi san sun (鯉口三寸) – “Three sun from the Guard” and the Cost of Impulse

Under shogunate law, this meant one thing: the sword had been officially drawn. Even if the blade had not yet fully left the saya—if it was extended by 9 cm (3 sun)—the samurai was considered ready to fight. If he had neither the right nor the reason to draw—it warranted punishment. Even seppuku (切腹), or ritual suicide, was not excluded.

Koiguchi san sun was therefore an irreversible moment—like pulling a trigger that had not yet fired, but already required consequence. There was no room for bluff.

In the world of samurai, every millimeter of the sword, every angle of its wear, and every line of movement carried meaning. Wearing a weapon was not a physical burden—it was a living declaration of identity, one that said everything before a single word was spoken.

The Ritual of Removing and Handing Over the Sword

→ Entering a Home – Surrendering the Weapon as a Sign of Trust and Subordination

The weapon was received by a special attendant—katanamochi (刀持ち – “sword bearer”)—who would place it on a dedicated stand (katana-kake 刀掛け) or in a storage space at the entrance.

The guest retained only the shorter sword—wakizashi (脇差)—used for defense indoors or, if necessary (and sometimes it was), for seppuku (Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?).

The host, on the other hand—if he held a higher status—did not have to remove his weapon, thereby emphasizing his dominant position.

→ Sword-Passing Rules Dependent on Rank

→ Sword-Passing Rules Dependent on Rank

The rules for handing over a sword were strictly dependent on the hierarchical relationship between the two individuals involved.

A person of lower rank would present the sword with both arms extended, palms facing upward, in a gesture of utmost respect—one hand beneath the tsuka (柄 – hilt), the other under the kojiri (鐺 – end of the scabbard).

A person of higher rank could accept or hand over the weapon with one hand, usually the left, grasping the middle of the saya (鞘 – scabbard), which signaled distance and confidence.

Additional gestures were not left to improvisation—every movement carried meaning. The exact forms could vary depending on the etiquette school prevailing in the time and place—for example, Ogasawara-ryū (小笠原流), which was observed at the shōgun's court from the Kamakura period onward.

→ Which Side and Which Hand? – The Language of Sword Gestures

- The tsuka (柄 – hilt) should be directed toward the recipient—this signified trust, as it enabled immediate drawing of the blade.

- If the tsuka pointed toward the giver, with the edge toward the recipient—it conveyed hostility or threat.

- The blade (ha 刃) was always directed toward the one giving the sword—receiving the weapon with the edge facing oneself was a sign of humility and acceptance of risk.

In every variation of this exchange, the symbolism was clear: who controls, who trusts, who dominates—it was all visible in the position of the hands, the angle of the sword, and the manner of grip.

→ Shiraha

This was a gesture of profound symbolic weight:

“I give you a weapon that you cannot refuse to return.

I give you my life—because I trust you will not misuse it.”

This form of presentation was reserved for:

- official ceremonies of sword bestowal (e.g., during the transition from chōnin to bushi),

- moments of the highest trust (e.g., as a pledge of loyalty to a daimyō),

- or death rituals, where the sword was given to someone preparing to commit seppuku.

The Sword’s Place and Position

When a samurai entered the home of another warrior or the residence of a daimyō, his first act was to remove his katana and place it beside him according to precise rules of etiquette. Sitting in seiza—knees on the mat, heels tucked under the body—the sword would be placed on the right side, with the tsuka (柄 – hilt) turned toward himself and the ha (刃 – edge) facing inward. This configuration made a swift draw impossible and was a clear sign of peace, respect, and deference. The sword was within reach but not ready for battle—and that spoke louder than a bow.

In the dōjō—the place of martial arts training—these rules have survived to this day. When not being worn, the sword is laid down on the right side, with the edge facing inward. Students never leave their katana just anywhere—the place where the weapon rests reflects their understanding of hierarchy, respect for the teacher (sensei), and for fellow students. Even the moment when the sword is laid at the entrance to the dōjō carries meaning—it marks the ritual of stepping into another world, a world of focus, learning, and devotion.

In private homes or official spaces, the display of the sword—most often on a katana-kake (刀掛け) stand—is also never arbitrary. Placing the tsuka on the left side (thus away from the viewer) with the blade facing upward and inward is a gesture of hospitality and non-aggression. This form of presentation was not only aesthetic but also social: it told guests, “you are safe here.” Conversely—a sword with its hilt turned to the right and its edge directed outward was a subtle signal of readiness for battle, commonly seen in inns, guardhouses, or places where samurai on duty gathered.

In an era where silence was considered the supreme virtue of a warrior, it was the sword that spoke first. Its presence and position could convey politeness, distance, disdain, or threat. And although we no longer live in a world where the placement of a katana could determine someone’s fate, the art of reading and speaking through the sword remains one of the most fascinating aspects of Japan’s warrior culture.

Etiquette of Sword Maintenance

Caring for the sword is caring for heritage—not only material, but spiritual. In a culture where the katana was called “the soul of the samurai,” every touch, every movement, and every gesture related to the blade carries meaning. Proper maintenance not only prolongs the artifact’s life—it becomes a practice that connects the modern individual with the centuries-old path of the warrior.

Conclusion

In the dōjō, practitioners of iaidō still train in the calm, precise movements of drawing and returning the sword. In modern Japan, the sword is no longer a tool of violence—it is a gesture. A gesture of memory, of focus, of dignity. The lesson of respect that the sword imparts is one that can be applied outside the training hall and beyond history—in daily life. In an age of noise and haste, the katana reminds us of the power of silence and the importance of presence. Respect for others, for place, and for tradition—that is the final lesson the sword has to offer.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Wakizashi – The Smaller Cousin of the Katana That Bore the Full Weight of Samurai Honor

Men Yoroi: Wrathful and Impenetrable Battle Masks of the Samurai

Samurai War Banners: Japanese Heraldry Under Which Battles Were Fought

10 Facts About Samurai That Are Often Misunderstood: Let's Discover the Real Person Behind the Armor

Katakiuchi – A License for Samurai Clan Revenge in the Era of the Edo Shogunate

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

→ Sword-Passing Rules Dependent on Rank

→ Sword-Passing Rules Dependent on Rank