The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

Society Behind the Mask

The significance of Majime can be interpreted on many levels - from personal sacrifice and discipline to a broadly understood dedication to the community and work culture. In the Japanese context, Majime goes beyond being just a character trait; it is a philosophy of life that translates into how people make decisions, build relationships, and contribute to social good. By promoting reliability and commitment, Majime is not just a personal choice but also a social expectation, fitting into a broader canon of values that shape Japanese culture and identity.

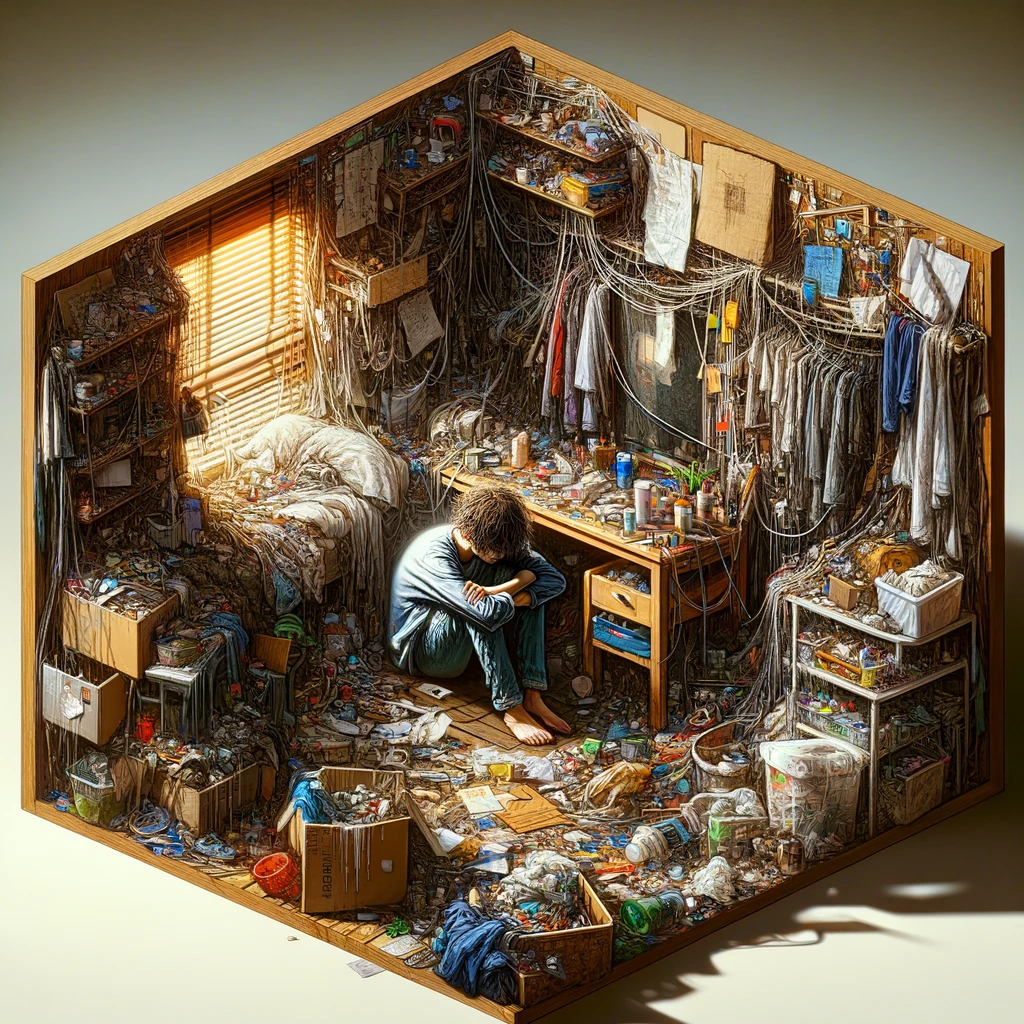

Majime, in short, is a respectable, honorable samurai, for whom the cause he fights for is everything. It's the quiet but very creative mangaka, who has devoted his entire life to his work. It's also the deeply mentally scarred individual, who, as a hikikomori, is "doomed" to 50 years of life in the solitary prison of his small apartment. It's also the young corporate employee, who works 16 hours a day and has practically sold his future for the ideal of the perfect worker. The concept of "Majime," like other ideals in every culture, can be both inspiring, motivating, and conducive to self-development, as well as enslaving, potentially destructive, and deadly. Let's examine it, for a better understanding of the Islanders.

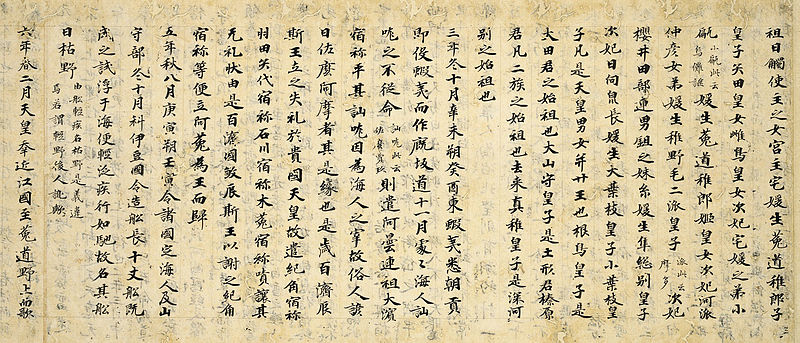

What Does “Majime” Mean (真面目)?

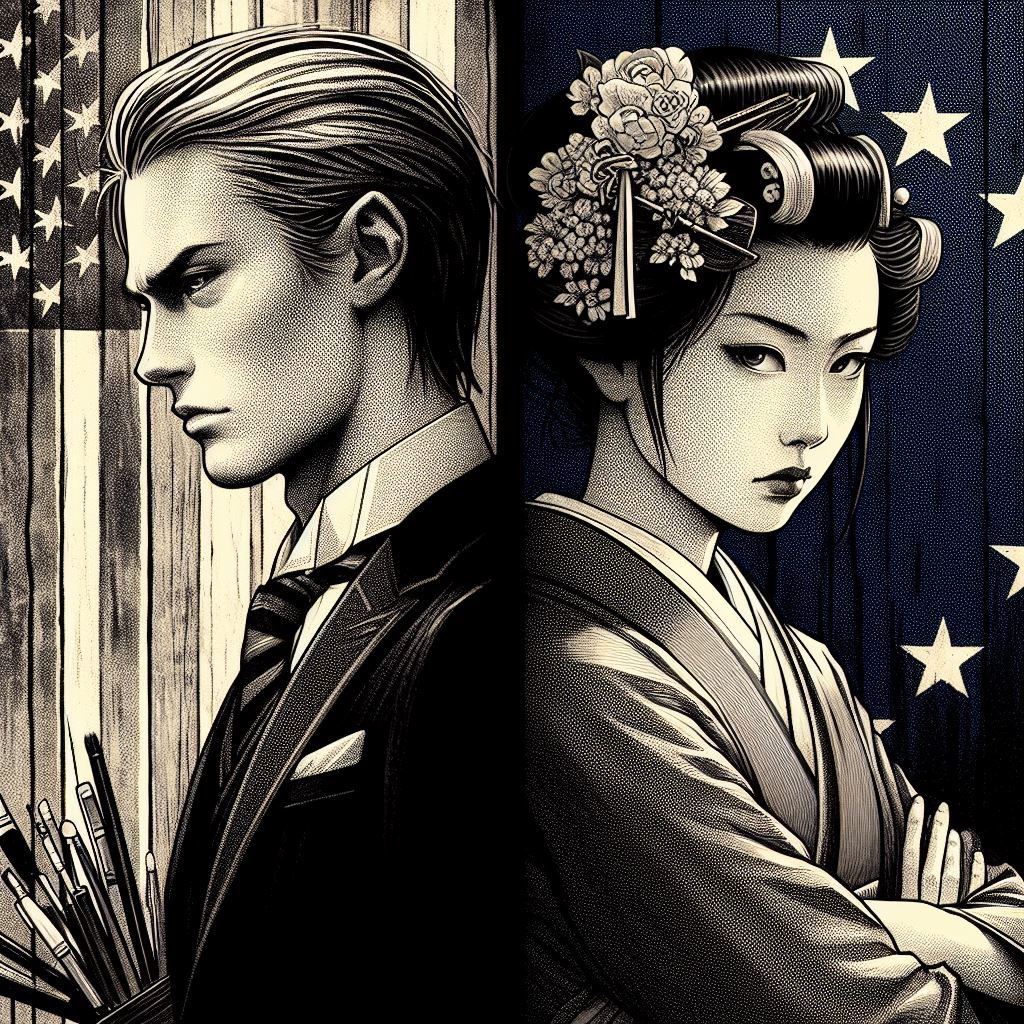

In modern Japanese history, especially during the Meiji period (1868-1912) and later, as Japan sought modernization and integration with the West, Majime began to play a role in adapting Western work practices while maintaining Japanese values and ethics. The work culture, which values effort, sacrifice, and loyalty, was and still is saturated with the spirit of Majime.

Today, Majime continues to serve a critical function in the Japanese workplace, education, and society, being a symbol of dedication and reliability. However, as Japan increasingly engages in global dialogue, the concept is also evolving, adapting to changing social norms and values that increasingly appreciate the balance between work and personal life as well as openness to emotions and individuality.

What is Majime – The Basics of the Concept

The concept of Majime refers to a trait deeply rooted in Japanese culture, valued both in private and professional life. Individuals described as majime (yes, it is an adjective) are seen as serious, reliable, responsible, and above all, devoted to their duties. They are characterized by deep engagement in what they do and unwavering honesty towards the people around them and the tasks entrusted to them.

The ideal of Majime somewhat reminds me of the Star Fleet officers from Star Trek, especially TNG. Such an association, I apologize.

Characteristic Features of Majime Individuals

▫ A serious approach to life: Majime individuals approach their duties with great seriousness, treating them with due respect and commitment. However, this does not mean a lack of a sense of humor, but rather a tendency to take matters seriously when the situation requires it.

▫ A serious approach to life: Majime individuals approach their duties with great seriousness, treating them with due respect and commitment. However, this does not mean a lack of a sense of humor, but rather a tendency to take matters seriously when the situation requires it.

▫ Reliability and honesty: These are people who value truth and transparency in their actions. Their honesty is a model to be emulated, both in professional relationships and personal ones.

▫ Responsibility: Majime also concerns a sense of responsibility for the tasks and duties entrusted. Individuals with such a character do not shirk responsibility but accept it, often even in situations requiring sacrifices.

▫ Engagement and loyalty: Engagement in work and loyalty to the employer or group are key elements of majime. This often involves a long-term commitment to an organization or cause.

The Role of Majime in Society

In a broader context, Majime stands out as a cultural archetype, reflecting a value deeply rooted in Japanese culture that emphasizes the importance of engagement, responsibility, and seriousness in the approach to life. Despite its complexity and demanding nature, majime is seen as an aspirational trait, motivating people to continuous development and improvement in harmony with the world around them.

Deeper Reflection

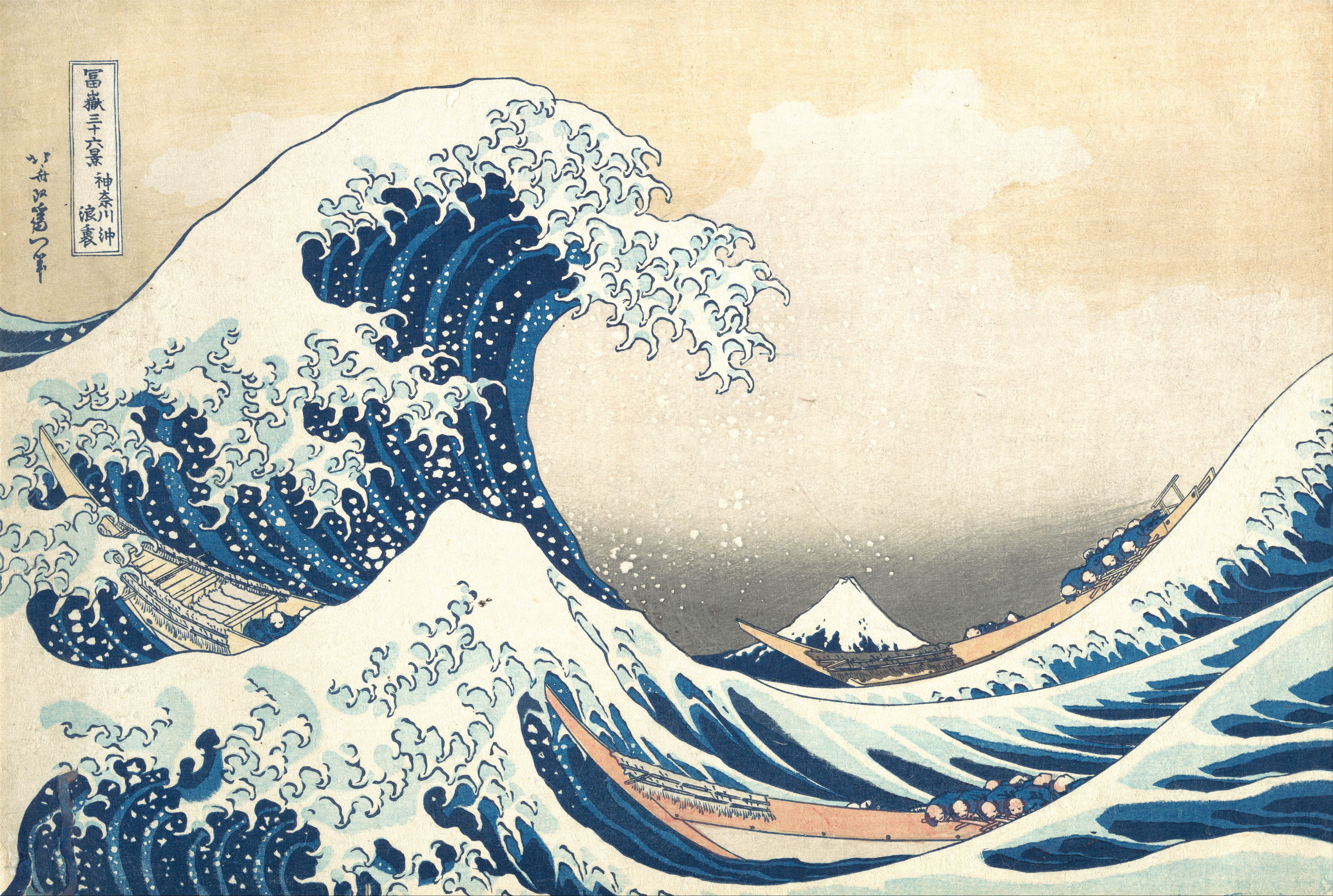

Zen Buddhism emphasizes finding deep meaning in daily activities and work, highlighting the value of mindfulness and engagement. In this context, Majime can be seen as an expression of this philosophy, manifesting through full engagement in tasks and a serious approach to life.

Shintoism, on the other hand, emphasizes purity, respect for nature, and harmony, which can be seen as striving for harmony in interpersonal relations, promoted by Majime.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on hierarchy, order, and interpersonal ethics, provides the framework for Majime.

Confucianism values, and which are closely associated with being a majime person. This can be best illustrated by the saying (Korean, not Japanese, but conveying the idea): "To be honest means to do what one ought to do in one's role, not what one would like to do." This statement can be understood as a benchmark for Asian ideas such as Confucian morality or the Majime mask. At the same time, it serves as a reminder to us, Europeans, of how different Japanese culture is - we should always avoid assuming Western contexts where they do not exist.

In the Japanese context, the Majime mask can have a whole range of consequences that can be dangerous, potentially fatal for the individual. Majime is an ideal that also serves as a means of exerting pressure. Social pressure, which is very strong, doubly so if it acts on the minds of young Japanese raised according to the ideals of majime from childhood. Pressure, which in effect brings about extreme social problems that are present only in Japan to such an extent.

Despite these challenges, Majime still plays a key role in shaping the individual and collective identity of the Japanese. It promotes values such as honesty, reliability, and commitment, which are fundamental to maintaining social harmony and supporting the common good. Like any philosophy or character trait, the key is to find a balance that allows for the preservation of one's identity and mental health while also contributing to the community and work culture.

Let's give the floor to other perspectives on viewing the ideal of majime.

Dōgen Zenji and Majime: The Pursuit of Authenticity

Dōgen Zenji and Majime: The Pursuit of Authenticity

Mindfulness Practice and Presence in the Moment: Dōgen placed great emphasis on the importance of being fully present in the moment and practicing mindfulness (Shikantaza). In the context of Majime, such presence and focus on the task at hand can be seen as an expression of deep commitment and seriousness in one's approach to life and duties. For Dōgen, full engagement in the present moment is the path to a deeper understanding of oneself and the world.

Authenticity and Expressing the True "Self": Dōgen taught that Zen practice leads to the discovery of one's true nature of existence. Within the context of Majime, this can be interpreted as an encouragement to nourish and express one's authentic identity, even in the face of social expectations and pressure. Authenticity and sincerity, which are valuable for a Majime individual, can be understood as a reflection of the deep inner truth that Dōgen placed at the center of Zen practice.

The Importance of Work and Daily Activities: Dōgen emphasized that enlightenment could be found in daily activities and work, which is closely related to the concept of Majime. Treating one's duties with the utmost seriousness and commitment, even if they seem trivial, is an expression of deep understanding and respect for life. This philosophical perspective encourages rethinking how even the simplest actions can be considered a path to spiritual growth and self-realization.

Tetsuro Watsuji and Majime: Interpersonal Dependency and Social Duties

Interdependence in Ningen: Watsuji emphasized that the human being (ningen) is by definition an interpersonal entity, which cannot exist independently of others. In this concept, Majime can be seen as an expression of responsibility and commitment that arises from fundamental interpersonal dependency. For Watsuji, being Majime is not just an individual choice but also a social obligation to contribute to the common good through serious and responsible approach to life.

The Role of Social Norms and Expectations: For Watsuji, ethics is inseparably linked to the specific social and cultural context in which we act. In Japanese society, where great importance is placed on group harmony and social duties, Majime can be seen as a key element in maintaining that harmony. By seriously treating one's own tasks and feeling responsible, Majime individuals contribute to social cohesion and the continuation of cultural traditions.

In summary, Tetsuro Watsuji's perspective on Majime emphasizes the concept's complexity and depth, combining individual pursuit of morality and ethics with indispensable interpersonal dependency and social expectations. Through this lens, Majime appears not only as a personal virtue but also as a key element in maintaining social harmony and cultural continuity.

Majime in Pop Culture

If we were to give examples of Majime appearing in Japanese pop culture, we could simply list all its works. All of them because it's hard to imagine a Japanese work (be it manga or film) in which the concept of Majime is not seen at the base. Nevertheless, below I provide a few such examples, which may facilitate spotting Majime motifs in other works in the future.

Anime and Manga

-

"Shouwa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu": This anime explores the lives of characters aspiring to become masters of rakugo (a Japanese form of narrative comedy), where majime traits are crucial for their personal and professional development. The main characters, who respect tradition and approach their craft with seriousness, perfectly reflect the spirit of Majime in their commitment and pursuit of excellence.

-

"Great Teacher Onizuka (GTO)": Although the main character, Eikichi Onizuka, may seem far from being majime at first glance, his serious approach to teaching and genuine concern for his students reveal a deeper meaning of this concept. Onizuka demonstrates that Majime can also mean deep commitment to the well-being of others, even if the methods are unconventional.

Video Games

-

"Persona" (series): The "Persona" series is known for exploring the psychological and social aspects of young people's lives. Characters in these games often face the pressure of being majime in school and society, while trying to discover and accept their true selves. The game shows a balance between social expectations and individual needs, emphasizing the importance of authenticity.

-

"Final Fantasy" (series): These RPG classics offer a deep insight into loyalty, honor, and seriousness through the prism of their complex plot and well-developed characters. The theme of Majime manifests in characters who take their roles and duties seriously, often putting the greater good above personal desires.

Impact on the Global Perception of Japanese Culture

The portrayal of Majime in Japanese pop culture has a significant impact on the global perception of Japan. Thanks to the international popularity of anime, manga, and Japanese video games, audiences worldwide have the opportunity to understand what seriousness, commitment, and responsibility mean in Japanese culture. Through these media, Majime is presented not only as a virtue but also as a trait that can lead to internal and external conflicts, providing a more complex and varied image of Japanese identity.

Summary

>> SEE SIMILAR ARTICLES

Ikigai as Life's Navigation Where to Seek the Japanese Secret of Happiness?

Japanese Gardens: A Piece of Art with a Surprising Ending - Discover the Secrets of Zen Gardens

Japanese Philosophy of Mono no Aware: The Practice of Mindful Being

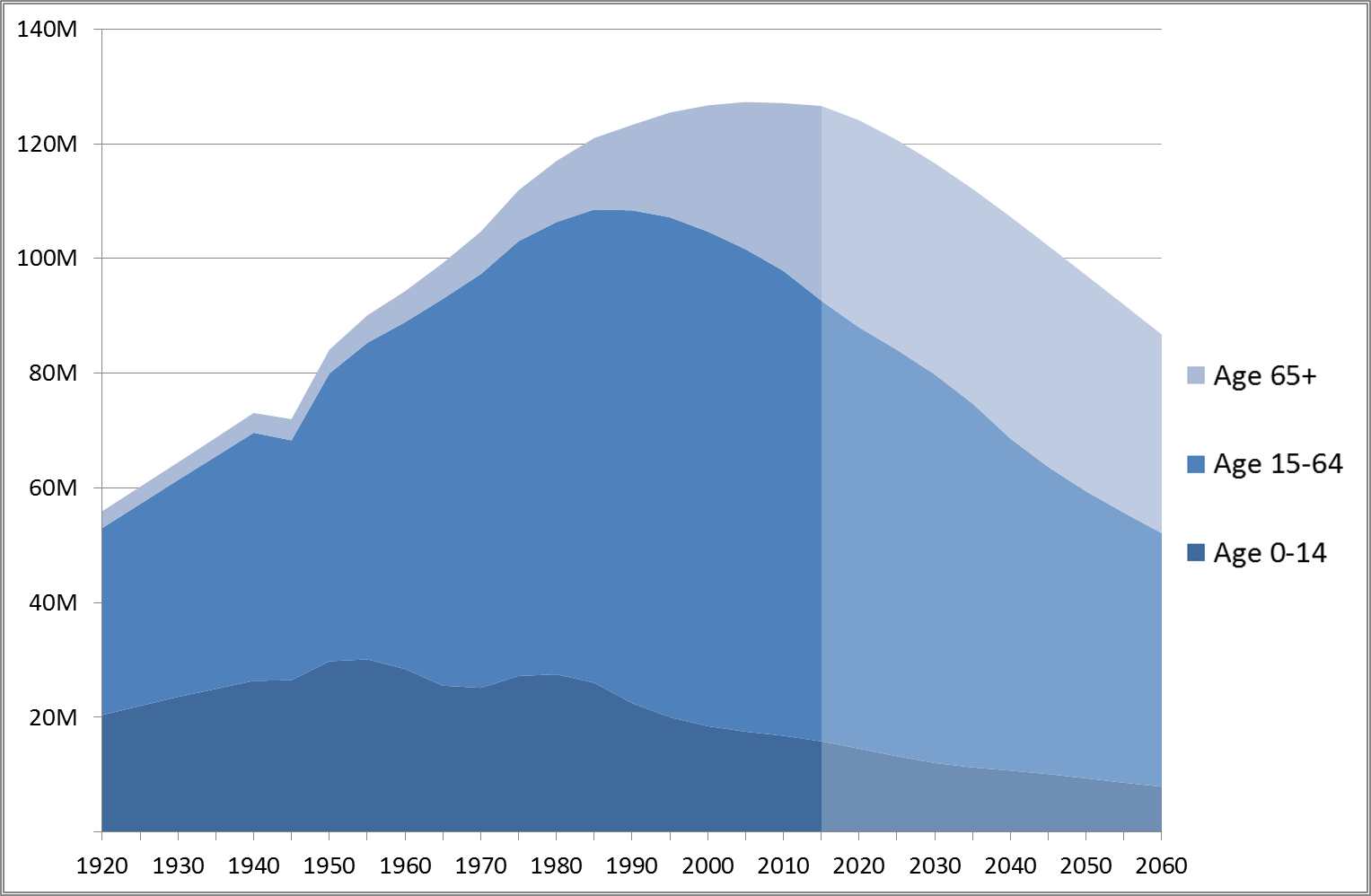

Parasite Singles: Japan's Demographic Dilemma at the Heart of Family

Beyond Stereotypes: The True Face of Hikikomori in Japan and Worldwide

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

▫

▫

Dōgen Zenji and Majime: The Pursuit of Authenticity

Dōgen Zenji and Majime: The Pursuit of Authenticity