Everything about the Samurai Katana - Structure, History, Customs, and Symbolism

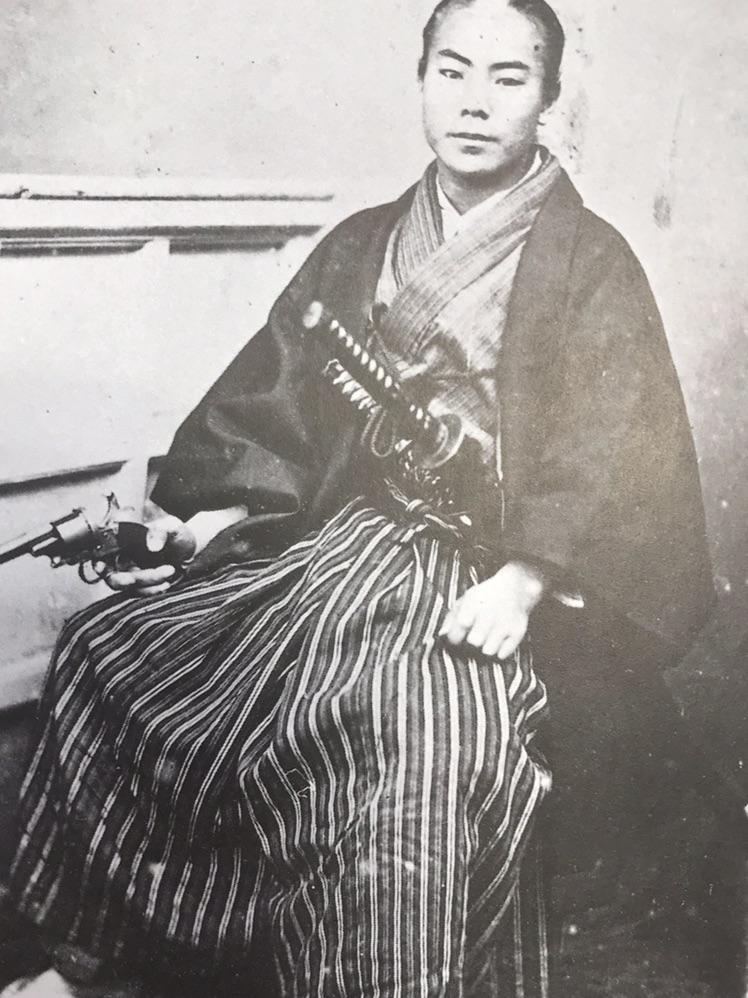

Katana is not merely a weapon

As you can see, there is a wealth of symbolism in pop culture regarding the katana as a tool of death, a carrier of honor, and a work of art. We often don't fully realize that these scenes and objects don't come from nowhere, they aren't just made up by the creator of a film or anime. They are symbols with centuries-old traditions and deep symbolism. It's good to get to know them a bit closer.

In today's article, we will take a closer look at the katana. We will discuss its nomenclature, history, and the structure of the whole and its individual elements. We will mention the material from which these swords are made and the process of their production, as well as the martial arts and handling of the katana. Finally, we will learn about various samurai customs related to the katana and its symbolism. We will tell the story of several of the most famous, legendary katanas, and we will try to relate all this also to our times and pop culture.

If this sounds interesting to you – welcome aboard!

What can we read from the name "katana"?

The word "katana" comes from the Japanese language, where it is written with the kanji 刀, which literally means "sword". This kanji often appears in combination with other characters, forming various concepts related to swords and bladed weapons.

First mentions

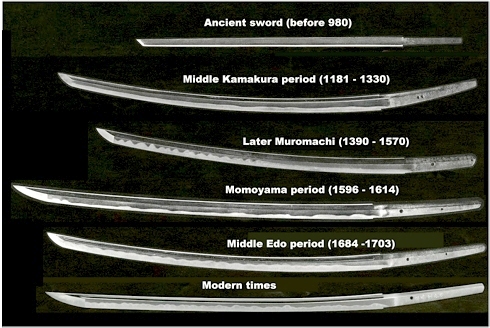

In medieval Japan, the katana gradually became more practical and easier to draw quickly than the tachi, responding to changing combat conditions that required quicker reactions. The meaning of the word evolved with the development of sword-making techniques and changing tactical needs of the samurai.

Other names and terms:

Other names and terms:

□ Tachi (太刀): Originally used sword, longer and worn differently than the katana.

□ Uchigatana (打刀): A sword worn with the blade facing up, simply an earlier version of the katana, more adapted to infantry combat.

□ Wakizashi (脇差): A shorter sword worn together with the katana; together they formed a pair known as "daisho" (大小).

□ Ken (剣): A general term for a sword, mainly used in reference to straight or double-edged swords.

□ Nihonto (日本刀): A term referring to Japanese swords in general, encompassing a wide range of traditional swords.

□ Shinken (真剣): "Real sword" – a term referring to functional, combat Japanese swords, as opposed to replicas or training swords.

The word "katana" is now globally recognized and associated not only with the sword itself but also with various aspects of Japanese culture, including philosophy, art, and history. This shows how dynamically this word has transformed from a specific technical term into a symbol of widely understood culture and heritage.

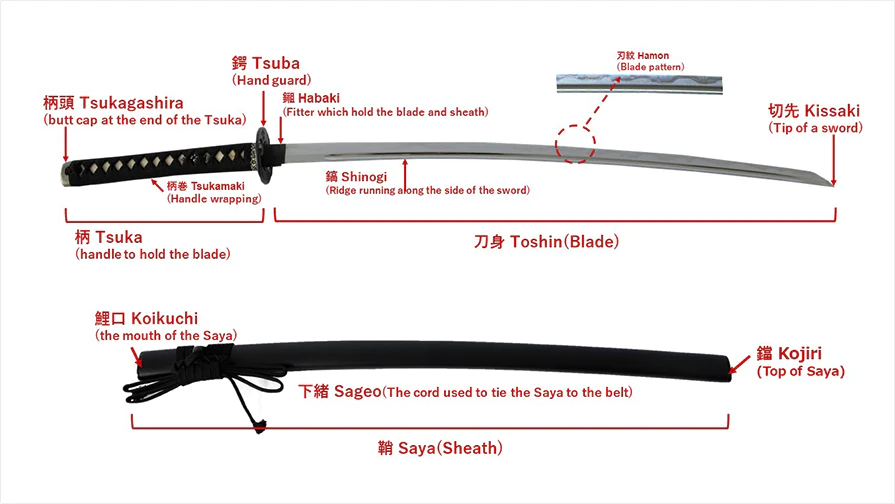

Construction of the Katana

The katana is not only a weapon but also a work of art, each element of which reflects a certain thought and has a specific symbolism. Here are the key elements of the katana's construction:

Blade (刃, ha):

■ Nagasa (刃長): The length of the blade, measured from the tsuba (handguard) to the kissaki (tip).

■ Kissaki (切先): The tip of the blade. It can take various forms, such as chōkissaki (very long), ōkissaki (large), or ko-kissaki (small).

■ Hamon (刃文): The temper line, a unique pattern on the blade resulting from the hardening process. Each swordsmith has their style of hamon, which can be straight (suguha) or wavy (midare).

▫ Menuki (目貫): Decorative elements placed under the wrapping, often depicting motifs from nature or symbolism related to the owner.

▫ Mekugi (目釘): Wooden pegs that pass through the nakago (tang), securing the handle to the blade.

■ Habaki (鎺): A metal collar placed on the nakago just at the tsuba, ensuring the stability of the blade in the saya (scabbard).

■ Tsuba (鍔): A guard that protects the user's hand. It may be ornamental and often contains artistic and symbolic elements reflecting the personality or status of the owner. From a non-functional but heraldic or symbolic perspective, the tsuba can be considered the most crucial part of the sword. (We have written a separate article about it here: tsuba).

■ Saya (鞘): A scabbard made of wood, often lacquered and decorated. It protects the blade and allows for safe carrying of the sword.

■ Seppa (切羽): Metal spacers on both sides of the tsuba, ensuring proper fitting and stability of the assembly.

Katanas are made from special steel

Tamahagane Steel (玉鋼)

Tamahagane is produced using a special technique involving the mixing of iron sands with charcoal and baking at very high temperatures for several days. The resulting material contains different levels of carbon, which is important for the properties of the final product, as differences in carbon content in different parts of the steel allow for the creation of a sword that is both hard and sharp at the edge and flexible and resistant to breaking at the spine. Tamahagane is prized for its purity and quality, which are essential for producing optimal sword blades.

Katana Manufacturing Process

Katana Manufacturing Process

Traditional forging, steel folding, and tempering

1). Selection of steel: The process begins with choosing the right steel, usually tamahagane and its variants.

2). Folding and forging: The steel is forged and folded multiple times. The folding process, known as "tanren" (鍛錬), aims to eliminate impurities and even out the carbon distribution in the steel, increasing its strength. Traditionally, the steel can be folded from several to a dozen times, creating thousands of thin layers, strengthening the metal structure. It is here, in the tanren process, that the smith's mastery becomes apparent. 2). Forming and shaping: After multiple folding and forging, the smith gives the sword its desired shape. At this stage, characteristic features of the katana, such as curvature (sori) and blade grind, are formed.

Legendary Smiths and Their Techniques: Masamune

Muramasa

Another well-known, though controversial, smith was Muramasa, who worked during the Muromachi period. His swords were prized for their sharpness but also feared for their supposed "bloodthirsty" nature. Legend has it that these swords had a tendency to incite aggression in their owners. More on this legend can be read here: cursed katanas).

The Art of Wielding a Katana

□ Kenjutsu (剣術)

□ Kenjutsu (剣術)

Kenjutsu, literally meaning "sword techniques," is a traditional Japanese martial art of sword fighting that originated in feudal Japan. This practice has its roots in the Kamakura period (1185-1333), when the first fencing schools were established to train samurais in the effective use of long swords. Kenjutsu encompasses a wide range of techniques, from basic cuts to complex combinations and forms (kata - 型 or 形).

In Kenjutsu, great emphasis is placed on stance, movement, precision, and tactical awareness. Practitioners learn various stances (kamae), cutting techniques (kiri), and blocking techniques (uke). Training is intense, with a strong focus on developing both physical and mental skills.

□ Iaido (居合道)

□ Iaido (居合道)

Iaido is the art of quickly drawing the sword, making a cut, and then sheathing it back. This art evolved from Iaijutsu, an ancient method of combat focusing on speed and precision. Iaido, as a more meditative practice, emphasizes the fluidity of movement and perfection of form aimed at achieving internal harmony.

The goal of Iaido is to perfect movements through the repetition of kata that simulate combat with an opponent. This practice also has a deep spiritual dimension, teaching humility, focus, and control over emotions.

► 合 (ai) - this character means "joining," "harmony," or "fitting" (not to be confused with the popular "love" (愛), which is also pronounced "ai" but is a completely different character). In martial arts, it often refers to the synchronization or harmony between the mind and body. ► 道 (dō) - this character, meaning "way" or "path," is commonly used in the names of Japanese martial arts (similar to judo, kendo) and other disciplines aiming for spiritual and physical refinement. It symbolizes the continuous pursuit of perfection and a philosophy of life, not just a collection of techniques. It is the "path" that one follows.

□ Kendo (剣道)

Kendo is practiced in a special uniform using a bamboo sword (shinai) and protective gear (bogu). Points are awarded for precise and correctly executed strikes to specific targets on the opponent's body, including the head, torso, and throat.

Symbolism of the Katana

The katana is not only a weapon of war but also one of the most popular symbols of Japan abroad. Importantly, it is not just an export item – the katana is genuinely a bearer of deep symbolism in Japanese culture.

Katana no Keishō

Every sword passed down in this ceremony carried the history of the family and was treated almost as a sacred object. In Japanese tradition, a sword is more than just a weapon; it is the "soul of the samurai" (侍の魂, samurai no tamashii). This ceremony emphasized that although samurai could die, their spirit – embodied by the sword – remained eternal, passing from generation to generation. Maintaining and caring for the sword, as well as mastering its use, were duties the new guardian had to fulfill, thereby honoring his ancestors and preparing to defend the family's honor.

In this way, the ceremony of passing down the sword in the culture of the samurai was not only a practical act of transferring a weapon but also a deeply emotional and spiritual experience that strengthened family ties and continued the traditions of the samurai.

Samurai customs related to katanas

Tameshigiri (試し切り) - Test Cutting

Katanakake (刀掛) - Katana Stand

In contemporary culture, katanakake appears in many film and television works that explore samurai themes, as well as in video games, where they form part of the set design. For example, in the anime "Samurai Champloo," one of the characteristic elements of the interiors where the characters are located are the katanakake stands with swords displayed on them. Similarly, in the game "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice," these stands can be seen in various locations, emphasizing authenticity and attention to detail in creating the historical world of the game. It is a very frequently occurring element that we see in countless numbers of games, anime, and even contemporary museums.

Chakusō (着装) - Dressing (Samurai Attire)

In modern culture, Chakusō is often depicted in Japanese historical dramas and films, showing the ceremonial preparations of a samurai for battle. For example, in the film "47 Ronin," characters were shown dressing in traditional samurai attire in a manner consistent with the tradition of Chakusō. In the world of games, these techniques are explored in titles such as "Total War: Shogun 2," where animations of samurais preparing for battle often include elements of Chakusō.

Tsukamaki (柄巻) - Handle Wrapping

Today, Tsukamaki is still admired and practiced by lovers of Japanese fencing around the world, often showcased in museums and exhibitions dedicated to Japanese swords. In popular culture, especially in films and series about samurais, such as "Shogun" or "Samurai X," Tsukamaki is shown in scenes where the main characters prepare their swords for battle. In the game "For Honor," where players can embody various historical warriors, including samurais, the technique of Tsukamaki is clearly visible in the accurately modeled katanas.

Nukitsuke (抜き付け) - Quick Sword Draw

The history of the nukitsuke technique is recorded in many classic Japanese treatises on fencing, including the famous "Heiho Kaden Sho" by the legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi, who lived at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Musashi describes nukitsuke as a fundamental technique in his book "Gorin no Sho" (The Book of Five Rings), where he emphasizes the importance of a quick and decisive first cut in samurai combat.

In the contemporary world, nukitsuke is often depicted in films, anime, and video games that explore Japanese samurai culture. I won't list specific titles – surely every reader has before their eyes the scene, so popular in films, games, and anime, where two samurais stand ready to fight, then one with one smooth and lightning-fast move draws the katana, carries out an attack, and kills the opponent, ending up standing with his back to the bleeding unfortunate.

Tōtogi (刀研ぎ) - Sword Polishing

Today, tōtogi is still practiced by craftsmen in Japan, being a subject of fascination not only among collectors and practitioners of martial arts but also among visitors to museums and exhibitions dedicated to samurai art. In mass culture, the process of tōtogi is sometimes shown in films, even those less traditional and non-Japanese, such as "Kill Bill," where the image of the katana polishing process is depicted as part of the preparations for the final confrontation. The game "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice" also pays homage to this technique, depicting how the main character uses the services of a craftsman to improve his weapon.

Legendary Katanas

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣)

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣)

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, also known as the Grass-Cutting Sword, is one of the three Imperial Regalia of Japan, alongside the Yata-no-Kagami mirror and the Yasakani-no-Magatama jewel. Legend has it that the sword was found in the body of the eight-headed dragon Yamata-no-Orochi by the storm god Susano-o. Kusanagi symbolizes strength and courage, and its story is deeply rooted in Shinto and Japanese mythology. The sword remains hidden from public view to this day, and its authenticity and appearance are shrouded in mystery.

Honjo Masamune (本庄正宗)

This sword, crafted by the renowned master smith Goro Nyudo Masamune during the Kamakura period, is considered one of the finest examples of Japanese swordcraft. The legendary sword was owned by many significant samurai and daimyō throughout Japanese history. Known for its unmatched sharpness and beauty, Honjo Masamune gained fame after the battle of Kawanakajima. The sword was lost after World War II and its current whereabouts remain unknown.

Dojigiri Yasutsuna (童子切安綱)

Dojigiri Yasutsuna (童子切安綱)

Dojigiri, or "Ogre-Cutting Sword," is one of the five famous swords of Japan, known as "Go-Hocho" (Five Treasures). Created by Yasutsuna, one of the oldest documented Japanese smiths, Dojigiri is most famous for its legend of defeating a great demon named Shuten Doji who terrorized the capital. This sword is prized for its effectiveness and beauty, as well as the mystical properties attributed to its ability to vanquish evil. It is currently housed in the Tokyo National Museum, where it is not only considered an important cultural artifact but also a symbol of heroic strength and courage.

Murasame (村雨)

Murasame, which means "Village Rain," is a legendary Japanese katana purported to have the power to summon rain. According to folklore, this sword belonged to a famous samurai who called upon the rain during droughts to relieve his people. Murasame has become synonymous with community care and the power of nature. The sword often appears in literature and pop culture as a symbol of mysterious powers and connection with the forces of nature. For instance, it appears in the game "Final Fantasy XV" as a hidden artifact that players can find and use as a powerful weapon capable of summoning rain.

Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu (数珠丸恒次)

Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu (数珠丸恒次)

Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu is one of the legendary swords of Japan, called "Tenka-Goken" or "Five Swords under the Heavens." The creator of this sword, Tsunetsugu, was one of the famous Masamune's disciples. The sword Juzumaru was known for its exceptional sharpness and beauty, and its name comes from the bead-like (juzu) patterns on its blade. Legend says the sword had the power to protect its owner from betrayal and misfortune, making it a sought-after artifact among samurais.

Summary

Samurais believed that their swords were living entities deserving of respect and care. This belief highlights the spiritual dimension of the katana, regarded as a reflection of the warrior's soul. This belief is even reflected in rituals and practices such as sword-cleaning and blessing ceremonies, which continue to be performed in Japan to this day. Many of these rituals are associated with Shinto, a religion that celebrates the harmony between nature, people, and objects.

Contemporary interest in katanas is manifested not only in collecting and ceremonies but also in global pop culture, where katanas often feature prominently in movies, games, and series. Thanks to their iconic form and mythical connotations, katanas have become symbols of honor, strength, and mysticism. They reflect not just technical perfection but also a deep connection between the craftsman and the material, compelling us to see them as more than just weapons - as true works of art.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Tsuba: A Japanese Masterpiece on the Katana - History and Manga Adaptations

Japanese Weaponry Under the Microscope: Dissection of a Samurai's Armor

Sword Master and Wordsmith Miyamoto Musashi: Samurai, Artist, and Philosopher

Tomoe Gozen, the Samurai Woman: 'A Warrior Worth a Thousand, Ready to Face a Demon or a God'

Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Other names and terms:

Other names and terms:

Katana Manufacturing Process

Katana Manufacturing Process □ Kenjutsu (剣術)

□ Kenjutsu (剣術) □ Iaido (居合道)

□ Iaido (居合道) Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣)

Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣) Dojigiri Yasutsuna (童子切安綱)

Dojigiri Yasutsuna (童子切安綱) Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu (数珠丸恒次)

Juzumaru-Tsunetsugu (数珠丸恒次)