"Gaman" is a central concept to understanding Japan. What does it have in common with European stoicism and what social disasters does its misunderstanding lead to?

Gaman - to bear difficulties in silence

Gaman - to bear difficulties in silence

Gaman is a Japanese concept that emphasizes patience, endurance, and the ability to bear hardship without publicly showing pain or frustration. It is a virtue deeply rooted in Japanese culture, often manifesting as stoic resilience in the face of adversity. The term "gaman" signifies both mental and emotional endurance, aimed at maintaining calm and dignity, even in the most challenging circumstances.

However, gaman also has its dark sides, especially in the context of contemporary social and health challenges. Excessive reliance on gaman can lead to the silencing of important health or social issues, as people may feel pressured not to complain or to seek help. This, in turn, can lead to stress, professional burnout, and other negative mental health outcomes.

Etymology of the word "Gaman"

Etymology of the word "Gaman"

The word "gaman" is composed of the kanji characters 我慢, where 我 means "I" or "self," and 慢 can be translated as "endure" or "suffer." Together, these two characters communicate the idea of enduring hardships with dignity and patience, reflecting a deeply rooted cultural value in Japan that promotes inner strength and resilience.

What exactly is the concept of Gaman and how to live according to it?

What exactly is the concept of Gaman and how to live according to it?

Gaman refers to endurance, patience, and the ability to bear difficulties without publicly showing pain or frustration. It is a value cherished both in personal and social contexts, reflecting a philosophy of unflappable endurance of adversity that has a long history in Japan, weaving into various aspects of daily life as well as philosophy.

Understanding Gaman – Through Literature

In practice, gaman is not just about enduring suffering in silence; it also involves maintaining dignity and control over one's emotions in the face of difficulties. In Japanese philosophy, heavily influenced by Buddhism and Shintoism, gaman also has a spiritual dimension, suggesting that through mastery and endurance, an individual can achieve a deeper state of inner peace and harmony.

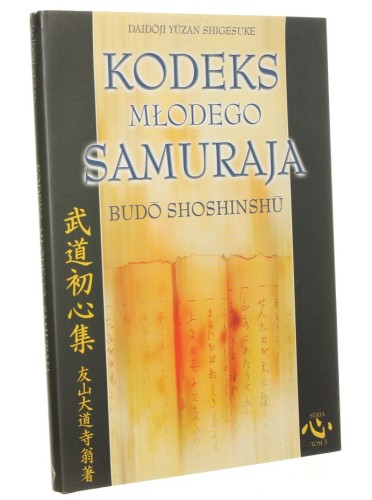

In "Budō Shoshinshu", Daidōji Yūzan focuses on many aspects of a samurai's life and behavior, including the necessity of maintaining calm and a stoic posture in the face of difficulties, which is closely related to gaman. He emphasizes the need for endurance and self-control, which are integral elements of gaman.

"Budō Shoshinshu" is therefore a valuable source for understanding how gaman was taught and conveyed to young samurai as an element of their training and personal development in Japanese culture.

Understanding Gaman – Through Contemporary Life

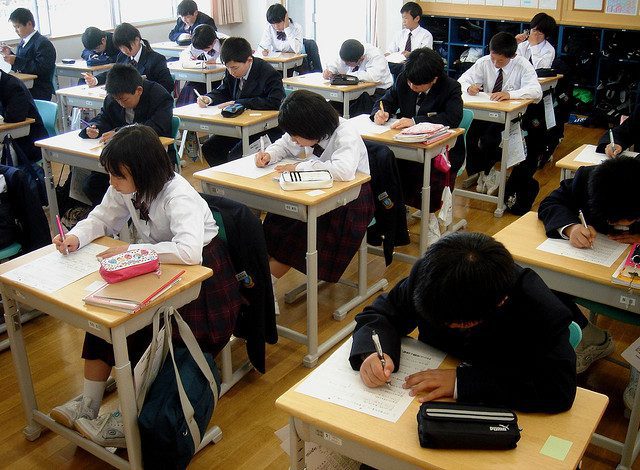

Gaman is applied in many aspects of Japanese daily life, from education to professional work and family life. In schools, students are encouraged to show gaman through perseverance in learning and respect for teachers, even if the material is difficult or demanding. Such an attitude is seen as preparation for adult life, where gaman is valuable in maintaining harmony in the workplace and society.

Gaman in the Workplace

Gaman in the Workplace

In the workplace, gaman manifests through hard work, long working hours, and often by sacrificing personal time for the good of the company. An example might be the behavior of employees during corporate crises, where they are expected to continue their tasks without complaints, despite, for example, temporary (or permanent) salary cuts while increasing the demands of working hours. Enduring this without showing even a hint of dissatisfaction is seen as a sign of professionalism and loyalty.

Gaman in Individual Psychology

Gaman in Individual Psychology

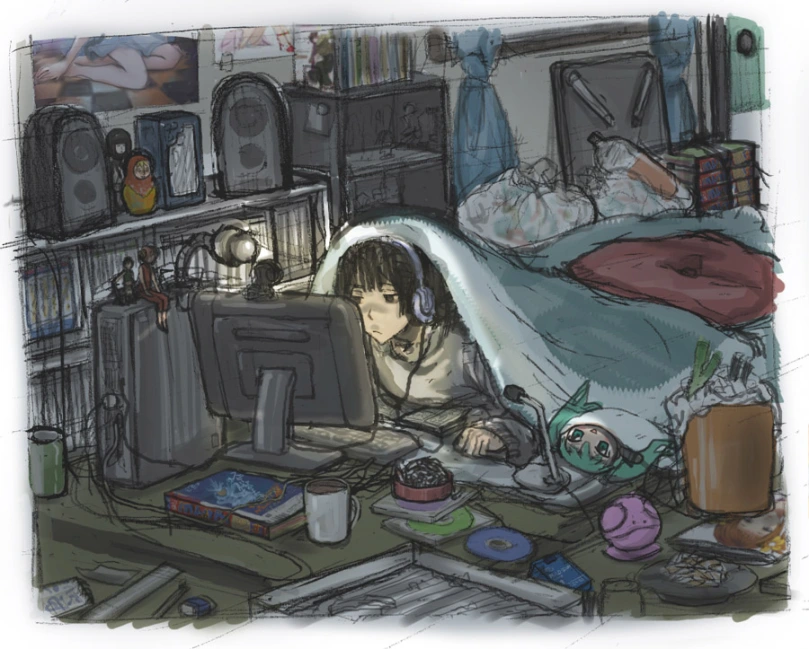

Additionally, the expectation that young adults will continue working in the gaman mode often contributes to delays or abandonment of starting a family, which supports the phenomenon of so-called "parasite singles" – adults who still live with their parents and delay taking full independence. This situation is one of the factors contributing to demographic problems in Japan, where the birth rate is one of the lowest in the world, leading to the aging of the society and associated very grim forecasts for the future of this nation.

Gaman – Individualism vs. Social Harmony

Stoicism – European Gaman?

Stoicism – European Gaman?

Issues arising from the colloquial understanding of gaman, such as excessive suppression of emotions or overburdening with duties, often lead to deeper reflections on the true meaning of this concept. In a more fundamental sense, gaman does not necessarily mean suffering in silence but rather finding internal strength to handle adversity with dignity. In this regard, gaman shares much with the European philosophy of Stoicism, especially as presented by Roman Stoics like Marcus Aurelius.

Stoicism, like gaman, emphasizes self-control but also understanding and acceptance of the external world as it is. Stoics, including Marcus Aurelius in his "Meditations," taught that it is not events themselves that upset us, but our judgments about them. Stoicism teaches that we should focus our efforts on what is within our power—our responses and decisions—while external circumstances, though often challenging, should not have the power to determine our inner peace.

Such an understanding of both Stoicism and gaman offers a new perspective on life, where challenges are seen not as obstacles but as integral elements of the path to wisdom. This approach not only reduces suffering but also enriches human life with a deeper meaning and purpose, teaching us how to live with dignity and calm in all circumstances.

Gaman in Contemporary Japanese Culture

Anime

Film

Education

Summary

Summary

Gaman is a key element that shapes Japanese culture and national identity. One might think that it is simply a value promoting endurance, but in reality, it is much more complex and affects various aspects of life from family to the workplace. Japan's history, from the era of the samurai to contemporary social and economic challenges, shows how the concept of gaman has helped society survive and adapt to changing conditions. In tough times, from natural disasters to financial crises, gaman has served as a coping mechanism, enabling Japanese society to maintain calm and good organization.

Technological development and social changes may require a new interpretation of gaman, balancing traditional values with the needs of modern society. For example, in business and technology, where the pace of innovation is fast, gaman might be reinterpreted not as discouraging change but as encouraging a methodical and thoughtful approach to problems and challenges.

>>SEE SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

Japanese Philosophy of Mono no Aware: The Practice of Mindful Being

Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection

Hokusai: The Master Who Soothed the Pain of Life's Tragedies in the Quest for Perfection

Johatsu – on average, every year over 80,000 Japanese people disappear. They call it 'evaporating.'

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Gaman - to bear difficulties in silence

Gaman - to bear difficulties in silence Etymology of the word "Gaman"

Etymology of the word "Gaman" What exactly is the concept of Gaman and how to live according to it?

What exactly is the concept of Gaman and how to live according to it? Gaman in the Workplace

Gaman in the Workplace Gaman in Individual Psychology

Gaman in Individual Psychology Stoicism – European Gaman?

Stoicism – European Gaman? Summary

Summary