Japanese spirits took him in – the wandering of Lafcadio Hearn, author of Kwaidan

“Japanese emotions do not express themselves in words; they rarely reveal themselves even in tone of voice – they manifest above all in acts of exquisite courtesy and kindness.”

As for many people of our generation, for me, Japan began in early childhood with anime (first Polonia 1, then Dragon Ball and Studio Ghibli) and video games. Yet my first encounter beyond the sphere of pop culture was Kwaidan by Lafcadio Hearn—a book full of dark, mysterious ghost stories, profoundly Japanese, initially rather alien, but fascinating. Today I know it was not just a book about ghosts.

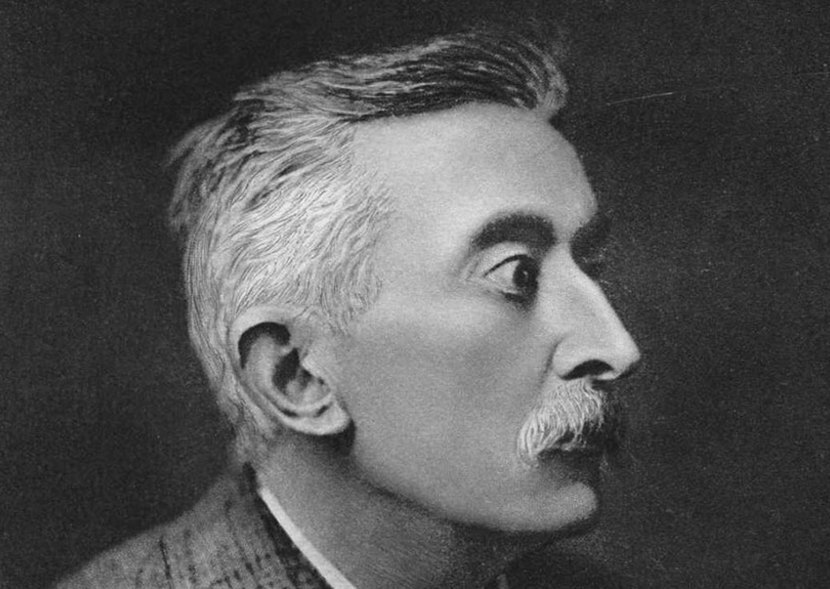

The author of this work was a man who long searched for a place for himself in the world. Lafcadio Hearn—son of a Greek woman and an Irishman. Abandoned by his mother at the age of four, and by his father at seven, little Lafcadio grew up under the care of a stern great-grandmother and aunts. His world was filled with silence, fear, and books. In his teenage years, an accident left him blind in his left eye, and the strain caused the other to grotesquely protrude outward. This disability made him even more alienated. He lived among shadows—both literally and metaphorically. He found no place for himself anywhere in Europe—he left penniless for America and became a reporter. He didn’t write about cultural events, politics, or celebrities—his articles dealt with the broken, the filthy, the marginalized—he wrote about prostitutes, gravediggers, and the insane. Lonely, poor, strange—as if he had always been preparing to live in a world of spirits.

A child of alienation and spiritual sensitivity

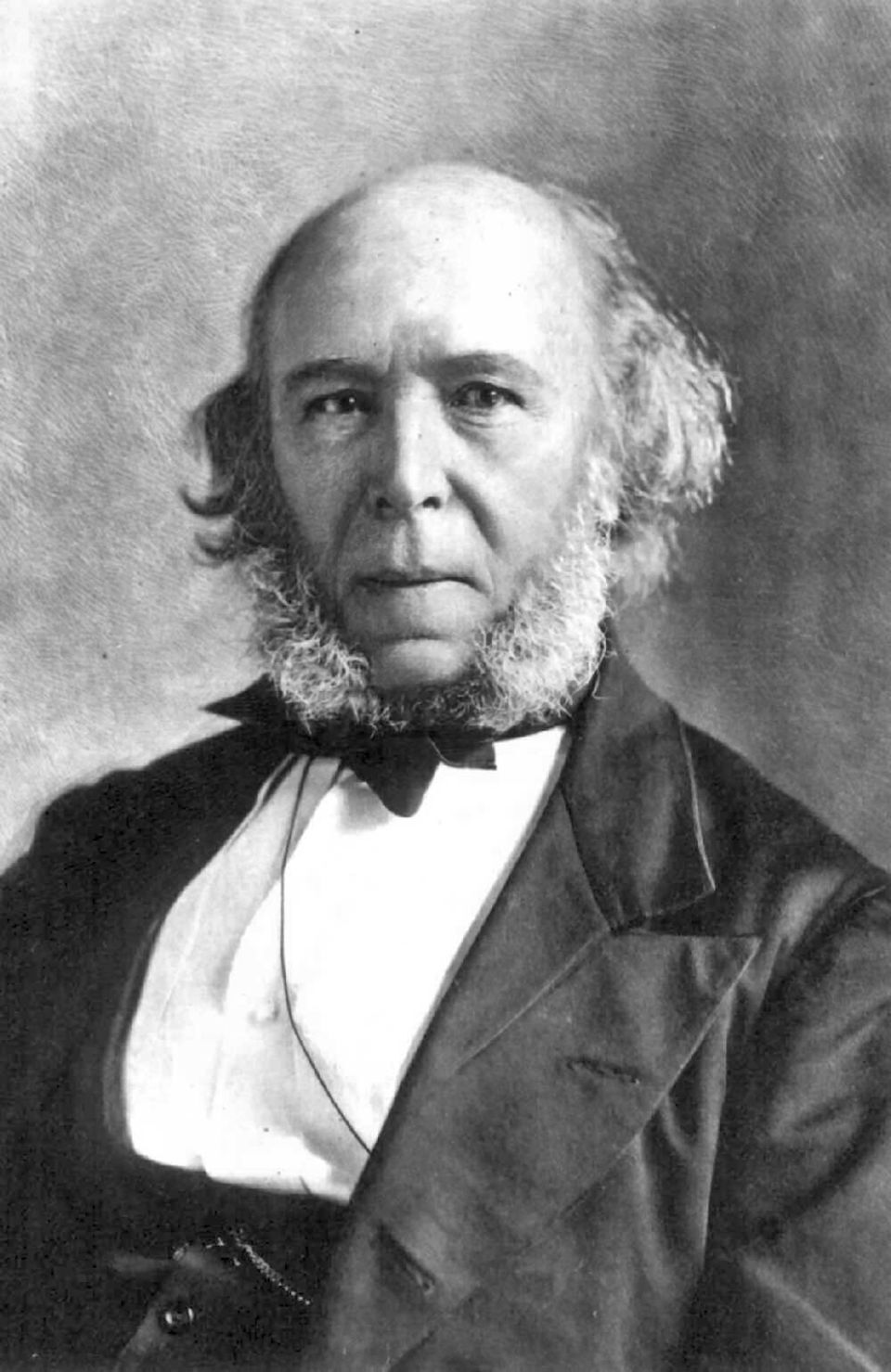

In adult life, Hearn developed his own philosophy of the soul, based on Buddhist and evolutionary influences, in which memory played a key role—not personal memory, but transgenerational consciousness. Under the influence of Herbert Spencer, he began to view the individual as composed of trillions of cells in which memories of past lives are stored. This view, which he termed “organic memory,” held that our thoughts, feelings, and reactions are echoes of the experiences of previous generations, encoded in our biological structure (a distant echo of a variation on this theme can be found here: "Parasite Eve" – Mitochondrial Eve in a Japanese Tale of Bodily Rebellion). According to Hearn, the “soul” is not something fixed—it is rather a dynamic network of ancestors, spirits, and impulses from centuries past, which momentarily congeals in our bodies only to later dissolve and take a new form. In this sense, even as a child, Hearn did not merely live in a world of spirits—he was their contemporary link, a being woven from countless fragments of prior existences.

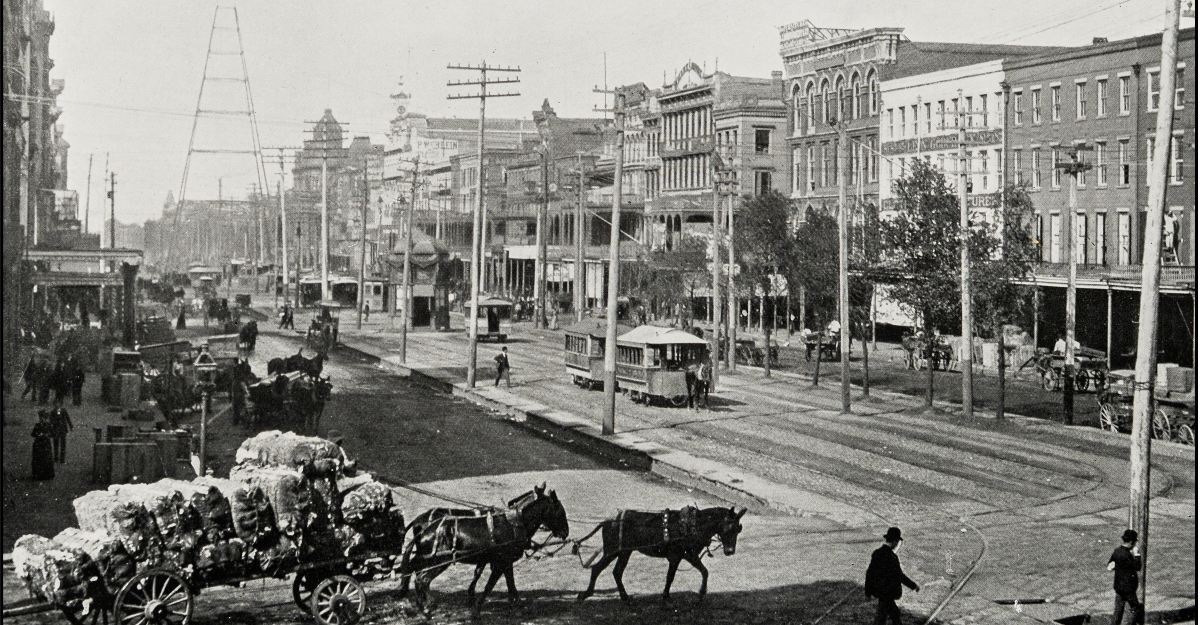

American wandering and literary initiation – learning to see the margins

For Hearn, writing became a form of therapy—perhaps even of religion. He was a romantic who found his temples in slaughterhouses and his prophets in funeral homes. In letters to friends, he wrote that he had devoted himself to the “religion of exoticism”—to all that was other, mismatched, rejected. Yet exoticism did not mean travel across the world, but journeys into what society pushed to the margins. It was there—in the grotesque, in deformation, in the whispers of the mad—that he heard the true melody of existence.

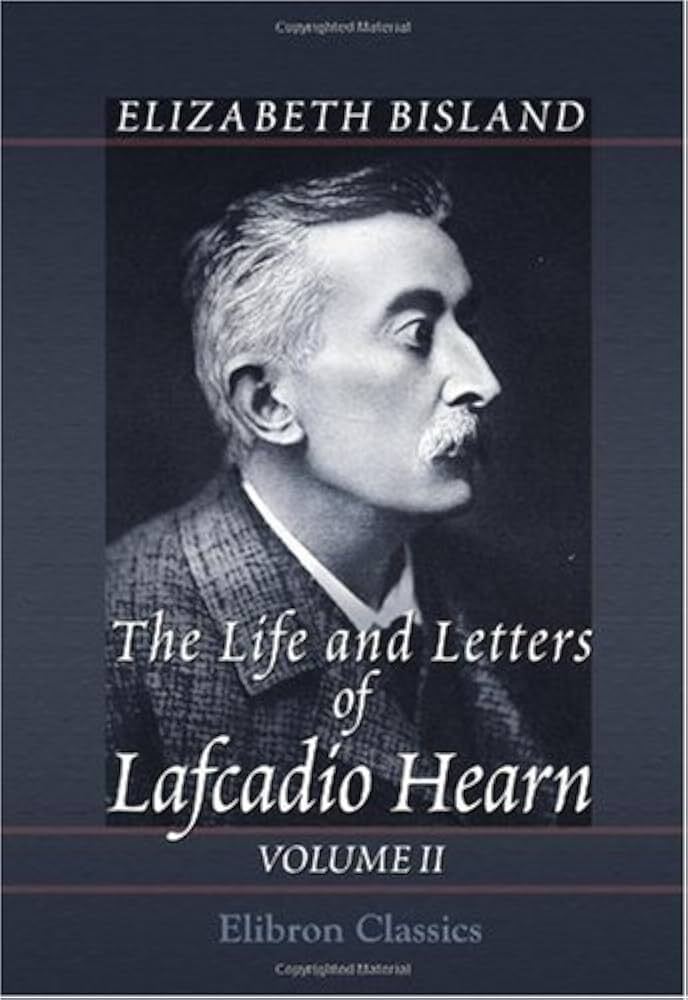

“Words have faces, gestures, manners. Sometimes they are unreadable, but that doesn’t matter. Their shadows are more beautiful than their meanings.”

(The Life and Letters of Lafcadio Hearn, Vol. II)

Thus was born the Hearn we remember—not as a correspondent, but as a poet of the invisible. Through language, through exclusion, and through attentiveness to what is overlooked, he was unknowingly preparing for his most important encounter—with Japan. For even before he set foot in Yokohama, he was already ready—not as a tourist, but as a restless yet curious spirit.

Japan as solace and revelation – the beginning of a new life

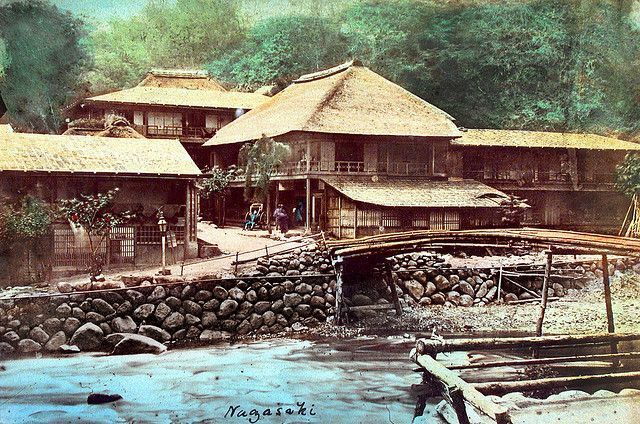

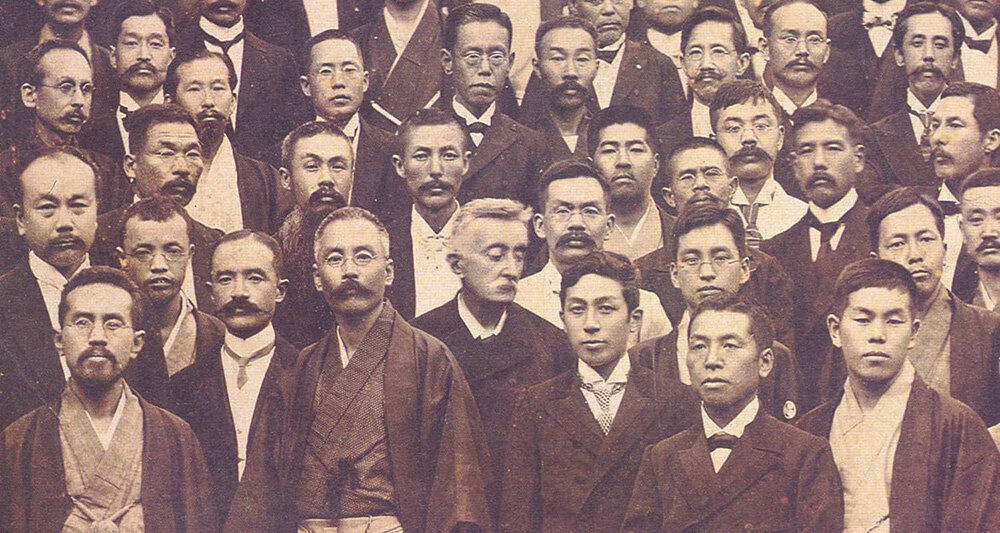

It was also there that he met Setsu, the daughter of a samurai—a quiet, faithful woman who did not speak English. Their love was like a conversation between two souls that needed no translation. He married her and took her surname—Koizumi. The Japanese first name he chose—Yakumo, or “Eight Clouds”—came from mythological poetry in the Kojiki, and symbolized mystery and protection. This gesture—taking her name, her lineage, her language—was not merely a formality. It was a spiritual decision: “I could not be a Greek, I could not be an Irishman, I was not fully American—but I could be Japanese. At least, that’s how I felt” (also from his letters).

He looked at the Japanese not as a colonizer or tourist, but as a pilgrim. And he saw something the West—according to him—had long since forsaken: the spiritual depth of simplicity. Courtesy was not a form but a value. Cleanliness—not an obsession, but a ritual. Art—not a luxury, but air.

Through Hearn, we learn to see Japan not through the prism of exoticism, but through authentic experience. We learn that a country is not just language, architecture, and cuisine—but the way people walk, breathe, and smile. Hearn taught us that Japan is not a place, but a state of being.

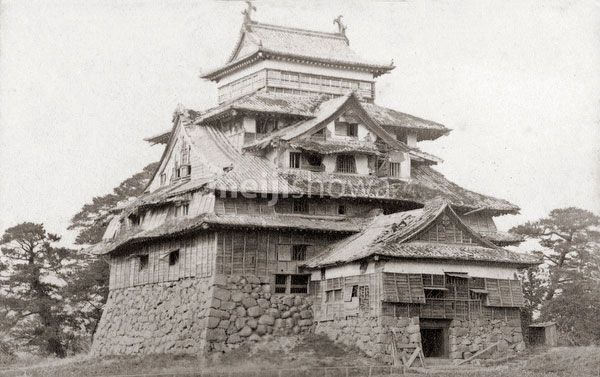

The aesthetics of old Japan – beauty that teaches

In his eyes, the life of ordinary people was a form of art more refined than anything he had seen in the West. A woman washing vegetables in a stream with the grace of a tea ceremony. An old man placing incense before a portrait of his deceased wife—as if silently conversing with another world. A paper parasol whose shadow fell upon a wall in a way that could never be planned—yet was perfect.

Meanwhile in Japan, rei—courtesy—was not merely a bow, but a philosophy. Silence did not signify emptiness, but a profound recognition of another’s presence. Hearn described it as a mysticism of form, where each gesture carried meaning. Thus was born his understanding of the Japanese spirit—the spirit of mono no aware, the ephemeral sorrow of impermanence that renders things more beautiful because they do not last.

But Hearn did not merely describe—he listened to language. He was in love with Japanese words the way a poet falls in love—not just with their meaning, but with their shadow, melody, story. In letters to Chamberlain, he explained that for him, words had “faces, manners, gestures… Sometimes they are unreadable, but it does not matter. Their shadows are more beautiful than their meanings.” For Hearn, the Japanese language was a translucent fabric through which something more could be glimpsed—the spirit of a nation.

– omotenashi – hospitality that expects nothing in return, based on anticipating the needs of the guest before they are spoken;

– natsukashii – a nostalgic longing for something past, but warm, serene;

– komorebi – sunlight filtering through leaves (more on that here: 10 Japanese Proverbs – Inspirations and Lessons Hidden in Ages-Old Characters);

– wabi and sabi – imperfection, solitude, silence, time – interwoven like moss on stone (more on that here: How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life).

Each of these words was for him like a living fragment of Japan—impossible to fully translate, but possible to feel, like the scent of rain or the warmth of a hand. Language, in his view, was a temple in which the most tender aspects of a people’s soul were kept.

And thus, step by step, day by day, Hearn built not only his home in Japan – but also our understanding of its culture. Through his eyes, through his senses, through his writer’s soul, we learn that aesthetics in Japan is not an embellishment of life – it is its foundation.

Shinto and Buddhism through the Eyes of a Romantic

Hearn, a romantic to his very core, did not seek dogmas so much as felt truths. That is why his spiritual immersion in the religions of Japan had nothing to do with a systematic attempt to understand their doctrines. Instead, he read them like poetry – he felt, experienced, and described them.

Shinto – the primal cult of Japan – spoke to him through gestures, through the smoke of incense rising in the shrine, through sacred trees bound with shimenawa rope (more about them here: A Profound Bond Between Humans and Trees in Japanese Culture and Ukiyo-e Art); through the mirror on the altar that did not reflect the face, but the soul. In it, Hearn saw something lacking in his own rationalized world – a living bond between humans and their ancestors, between community and nature. He wrote:

On this spiritual map, there were three circles of ancestor worship – the household, where the butsudan altar became a place of daily dialogue with the dead; the communal, where local deities – ujigami – were the souls of founders and guardians of a given village; and the imperial, in which the entire nation turned to Amaterasu, the divine ancestress of the ruling family.

But there was also Buddhism – subtle, melancholic, devoid of a creator god, open to uncertainty and emptiness. Here, Hearn felt at home. Having rejected Catholic dogma and Western individualism, he found in Buddhist teachings an explanation for his own obsessions – the fragility of existence, the illusion of the “self,” the endless cycle of reincarnations. In Buddhism, as in the philosophy of Herbert Spencer, he saw the idea that the individual is a temporary cluster of cells and memories, which will disperse only to be reborn – in another form, in another place.

“What is the soul?” he wrote. “It is infinite complexity – we are all an eternal mixture of fragments of past lives.”

Spirits – in Japan – were not monsters from gothic novels. They were part of life. They watched over, taught, reminded. Hearn felt their presence everywhere – in the rusted bells of temples, in the whispers of children’s songs, in the scent of rain falling on a stone bridge. Japan was for him a haunted country – but not by horror, rather by the kindness of ancestors, by the gentle touch of eternity.

– Kami – deity, spirit, but also any natural phenomenon that fills a person with reverence. For Hearn, kami was not something external – it was the light within a leaf, an echo in a temple courtyard, the mist over mountain forests.

– Kagami – mirror – the central object in a Shinto shrine. Hearn was moved when he discovered a linguistic subtlety: remove the syllable ga (meaning “I” or “self”) from the word, and what remains is kami.

– That is no coincidence, he wrote. That is revelation. “Remove the ego, and you will see the god.” In this small linguistic play lay the entire message of his spiritual journey.

Lafcadio Hearn as a European Philosopher of Japanese Spirituality

And he did so not through prayer, but through philosophy. One of the most important impulses in his spiritual thought was his encounter with the work of Herbert Spencer, the evolutionist who sought to grasp the entire world – from biology to society – within one great theory of progress. Hearn absorbed his monumental System of Synthetic Philosophy with greater reverence than he had ever felt for sacred books.

Spencer taught him to see the human not as an individuality, but as a temporary aggregation of cells. “We are only a transient conglomerate of trillions of living units,” Hearn wrote in awe. Cells that after death would decompose and pass into other forms of life – in soil, in trees, in a child. This was not so much reincarnation, as the eternal circulation of biological memory, where every emotion and every impulse leaves a trace in the fabric of the world.

“The mind is as much a composite of souls as the body is of cells.”

It was this vision – radically un-Christian, profoundly Japanese in its essence – that allowed him to enter Japan’s spiritual landscape without the moral superiority and disdain so common in the writings of other European authors and travelers. While Sir Ernest Satow mocked Shinto as a childish religion, and Chamberlain called it superstition, Hearn wrote with tenderness:

“It is not rationality that makes a religion important. It is its emotional power, its ability to soothe, to move, to uplift.”

In his eyes, Japanese spirituality—ambiguous, without a central dogma, fluid like the mist drifting over a Buddhist garden—was true precisely because it was aesthetic. Because it did not attempt to be an objective truth, but a lived one.

“A Japanese man may not believe in ghosts—yet on a stormy night he leaves a little sake on the window sill. Not for himself, but for those who may still remember…”

Instead of battling the illusion of the ego, the Japanese sidestepped it. Instead of searching for the “self,” they allowed themselves to be guided by the community—both the living and the dead. Hearn was enchanted by this. He believed that the ego, that inflated Western construct, was the source of loneliness, suffering, and aggression. And that it was precisely this ego, he wrote, which must be removed from the mirror in order to glimpse the reflection of a god:

“Remove ‘ga’ from kagami, and you are left with kami.”

“I do not believe in ghosts in the way I do not believe in fairy tales. But I believe in what ghosts and fairy tales do to our hearts.”

In this sense, Japan—a land of kwaidan, of unfinished stories and ceremonies—was not exotic to him, but a deeply metaphysical experience. He did not seek the “real” Japan—but rather the Japan that exists in experience. He did not seek objective religion—but an emotion that makes a child bow before a grandmother’s portrait. And that is why his writing is not merely a source of knowledge about Japan—it is a meditation on its soul.

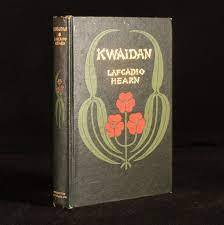

Kwaidan – Japanese Spirits That Spoke in English

Hearn wrote it as Koizumi Yakumo, husband of a Japanese woman, teacher of English in Japanese schools, a man who had passed to the other side of the mirror. But Kwaidan is not just a collection of scary tales, as the title (an archaic form of kaidan, or ghost story) might suggest. It is a lyrical meditation on impermanence, on tenderness toward those who have passed, on beauty embedded in fear, and on the spiritual landscape of Japan, where the boundary between life and death was never sharply drawn.

“One cannot truly understand Japan unless one believes in ghosts.”

And though he understood this in his own, Western way, he did not try to disenchant, expose, or dissect Japan—on the contrary, he allowed its spirits to speak in their own voice.

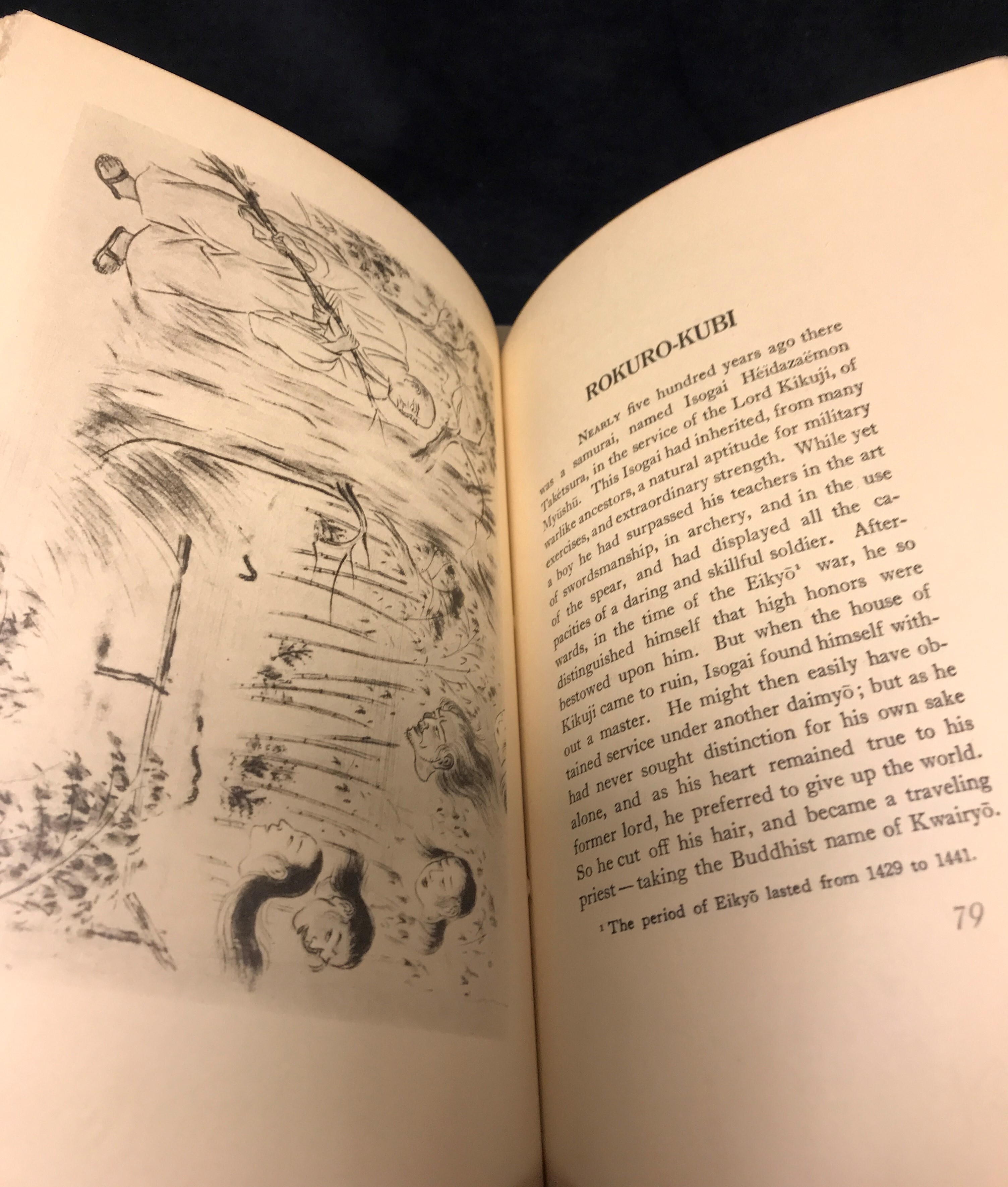

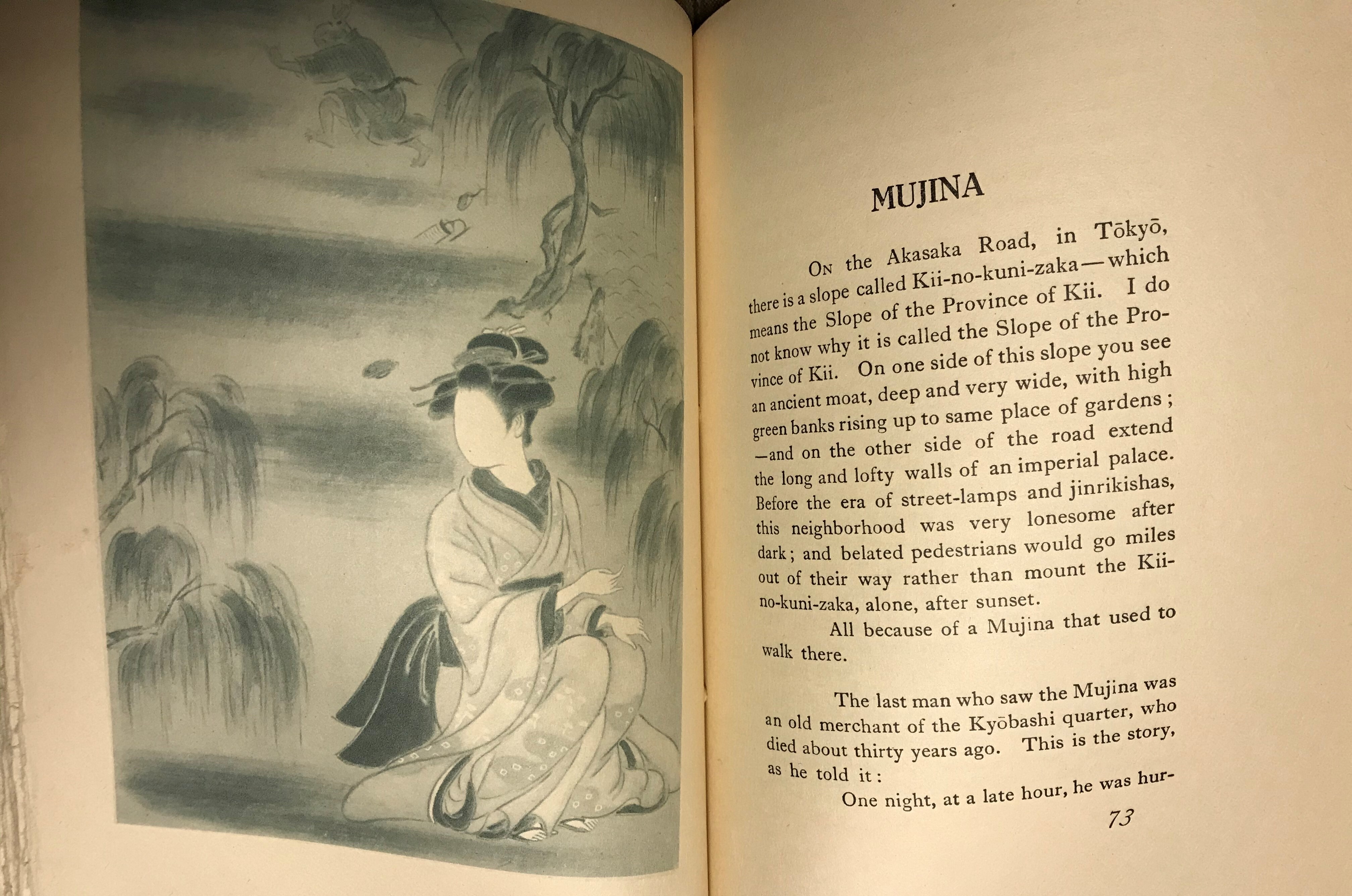

Stories like Miminashi Hōichi (“Hōichi the Earless”), Yuki-Onna (“The Snow Woman”), or Mujina are now classics of Japanese horror culture. But it is not fear that makes them unforgettable. It is melancholy. It is what the Japanese call mono no aware—the gentle awareness of the transience of things. In Kwaidan, ghosts do not terrify—they remind. They do not seek revenge—they seek remembrance.

In the book, Hearn never imposes his own narrative. He lowers his voice, kneels by the fire, and allows the old men, the monks, the women whose names no one remembers, to speak. Their stories breathe with chill—but also with tenderness. It is a book best read on a winter’s night.

The legacy of Kwaidan is vast. Its 1964 film adaptation, directed by Masaki Kobayashi, is still considered one of the masterpieces of world cinema. But Kwaidan’s greater influence lay elsewhere—in the way the West began to view Japan. Not as a land of samurai and exoticism, but as a space of spiritual resonance, where every object and every memory has a soul.

What Do We Owe Koizumi Yakumo – Hearn?

His writings shaped the development of Japanese studies—not through academic systematization, but through sensual closeness. He inspired Yanagita Kunio, the father of Japanese ethnology, who saw in Kwaidan and Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan a confirmation of the value of folk culture. He delighted Nagai Kafū, who, like Hearn, sought the “old Edo” in the ever-changing Tokyo. Today, echoes of his thought can be found in Alan Booth and Alex Kerr—modern-day chroniclers of a vanishing Japan, of wooden houses, shadows, rustling curtains, and the silence of the world’s threshold.

Koizumi Yakumo is a spiritual patron of an era in which identities interweave and traditions meet on the borders of languages and cultures. As his biographer wrote:

“He did not belong to Greece, he did not belong to Ireland, he did not belong to Japan. And yet, he belonged to all.”

Let him remain with us as one who teaches us how to look—at beauty, at shadow, at what fades away. And at what—though invisible—endures.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

10 Urban Myths of Tokyo – Discovering 21st Century Japanese Folklore

Warai Onna – The Yōkai from the Mountains of Shikoku Who Brings Psychosis and Death Through Laughter

Tsukumogami – Bizarre Youkai Demons Formed from Everyday Objects

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!