Warai Onna – The Yōkai from the Mountains of Shikoku Who Brings Psychosis and Death Through Laughter

Don’t Go into the Mountains on the Ninth

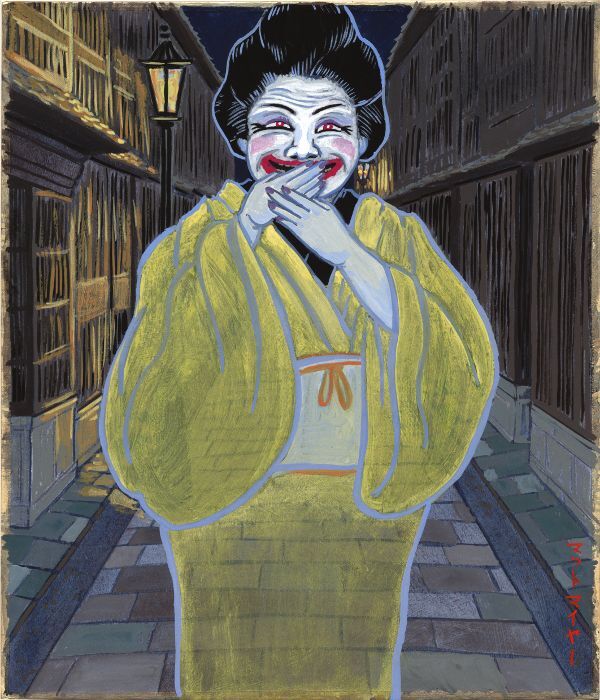

Japan knows many ghosts – from lakes, from stories, from blood – but warai onna is among the most disturbing. Because she does not need violence. She brings no fire or poison. Her laugh is enough – a laugh that seems human, but is not. A laugh that infects like a virus, like a childhood memory that suddenly grows too sharp and cuts. A laugh that compels you to laugh until you’re breathless – and then further still. A laugh that causes psychosis, incites dreadful acts, and in the end – mercilessly steals not only the senses but life itself.

This tale is not merely a legend. It is about laughter – the most primal form of expression, which in Japanese culture has always been more than just a sign of joy. Here, laughter becomes a mask, behind which pain, shame, loneliness, or madness may hide. Warai onna is not just a yōkai – she is a reminder that what is social can become demonic, and that what is familiar can suddenly speak in the voice of chaos. She shows how laughter can shatter the structure of our neatly arranged, socially acceptable reality – irrevocably, and beyond repair.

The Legend…

— It was a long time ago — she says — when memories of what lurks in the mountains still lived, and youth, as always, was more confident than wise.

In the heart of the mountains, time changes. Hours stretch in the shadow of pines, and sounds fade, as if afraid to wake something better left sleeping. It was there, among the trunks of mossy trees, that they saw her. She stood on the edge of a clearing – a young woman, barely seventeen, with long, loosely flowing hair and a charming face, beautiful in her own way. She smiled. She giggled softly, as if some joke had amused her.

At first, they thought she was local – perhaps a woodcutter’s daughter. They approached to ask if she needed help – after all, she was alone in the remote mountains. One of them – Kenji – mumbled a joke, and suddenly they all started laughing. A normal, light-hearted laugh. But her laugh, now strangely coming from behind the four friends, grew louder. Higher. Sharper. And then... unnaturally long. Kenji began laughing harder, his face turned purple, and he collapsed to his knees, still laughing so violently that his whole body shook. He kept laughing even when his lungs gave out. He fell into the snow, eyes wide open, with a smile frozen like a mask.

By the time they reached the forest’s edge, the woman’s laughter was everywhere. In the crack of branches. In the murmur of the stream. In the deep rumble of the earth. Ryō began to hear Masaru and Daisuke laughing at him. Masaru was convinced Ryō was whispering insults in his ear. Daisuke saw the faces of his friends turn into the face of that woman – with a wide, never-ending smile. Then the knives came out. Blinded by the madness of laughter, they tore into each other like wild beasts.

When the villagers found their bodies a few days later, it was clear they had not been killed by animals. Their faces – even Kenji’s – were frozen in laughter, which was no longer joy, but a scream from souls that would never know peace.

The old woman falls silent. For they had encountered – warai onna.

Etymology: “warai onna”

The verb warau (笑う) does not always signify joy. Depending on context, it can carry shades of mockery, embarrassment, dread, or even pain. Japanese culture does not perceive laughter solely as a positive phenomenon. Warai can be a mask – either protective or aggressive. In Nō theater, a character with a smiling mask can be ominous. In Buddhist texts, laughter is sometimes a space of illusion – a symbol of the world of appearances, māyā. Laughter may also signal a loss of control – a symptom of madness. In the case of warai onna, laughter ceases to be an expression of positive emotion – it becomes a weapon of destruction, a psychological contagion that infects and annihilates the mind.

Folklore also includes other entities with similar effects. One such being is kerakera onna (けらけら女) – a character from the works of Toriyama Sekien, who, although appearing mainly in the red-light districts of cities rather than in the mountains, also kills through laughter. Her name – kerakera – is an onomatopoeia describing a loud, cackling laugh. Today, she is often considered the urban counterpart of warai onna.

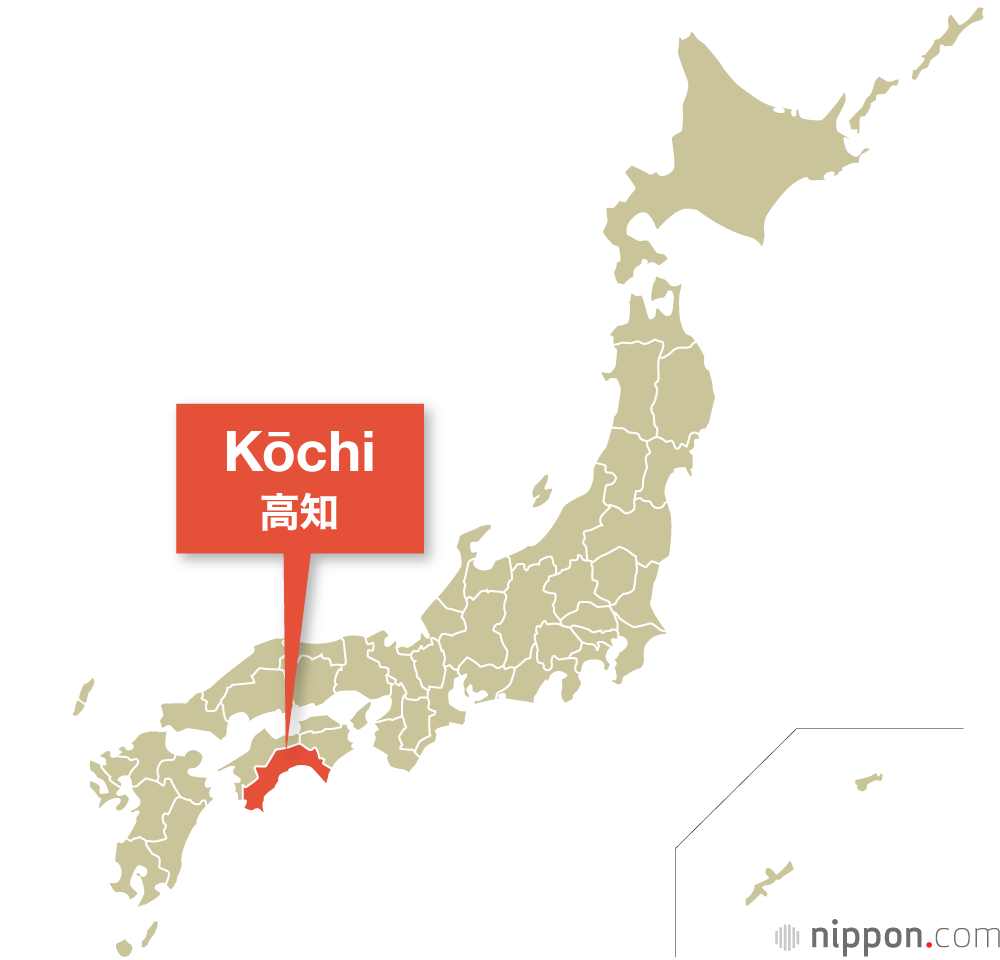

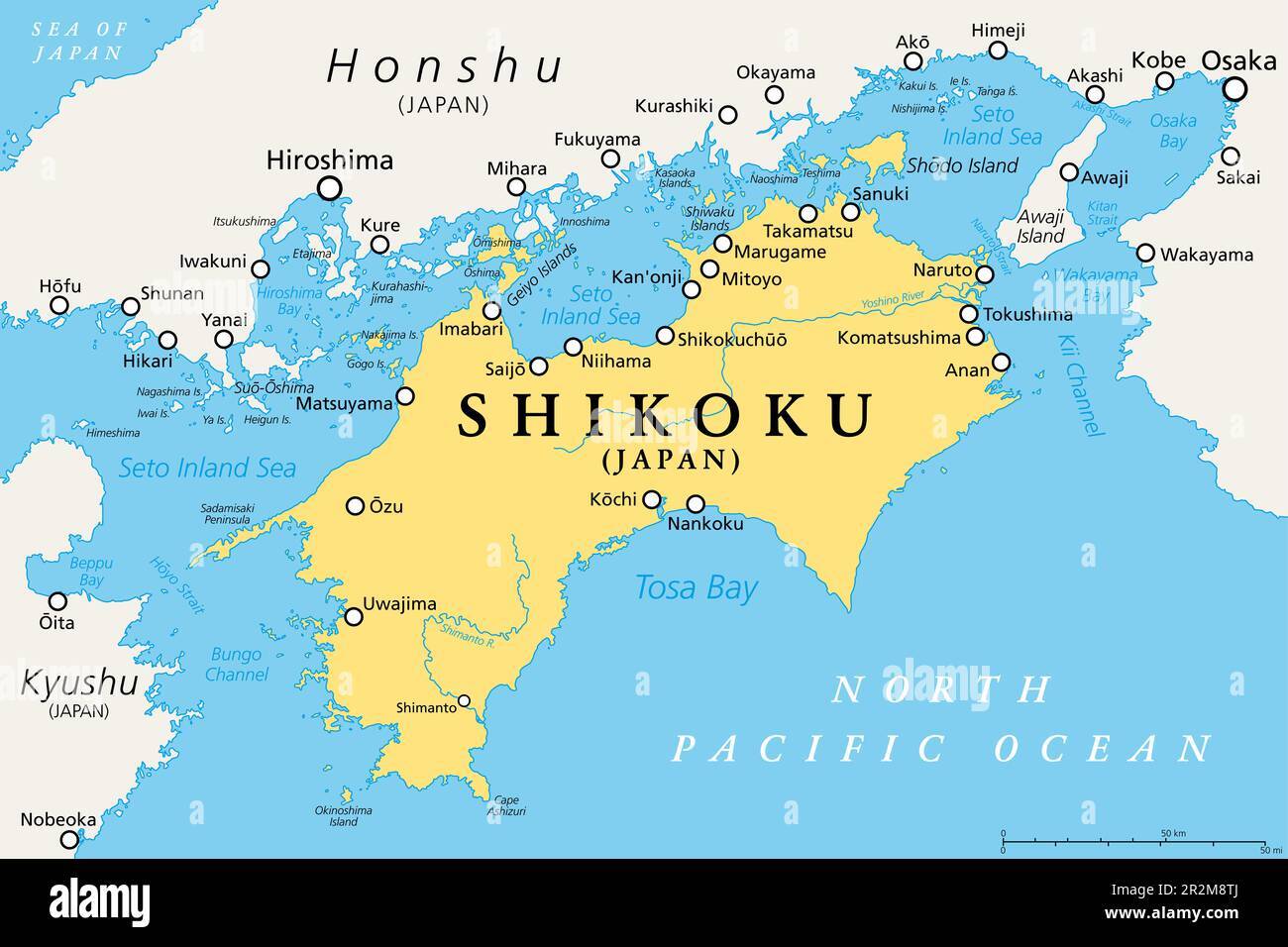

She Came from the Mountains of Kōchi, Shikoku

One of the most important sources is the illustrated monster book titled Tosa Bakemono Ehon (土佐化物絵本) — “The Picture Book of Monsters from the Province of Tosa.” Tosa is the old name for the region that today forms the southern part of Kōchi Prefecture. In this book, warai onna is described as one of the three most dangerous supernatural beings of the region, alongside “The Red-Head of Katsugase” (勝賀瀬の赤頭) and “The White Crone of Motoyama” (本山の白姥).

Legend has it that warai onna appears only on specific days of the month: the first, ninth, and seventeenth days of each lunar month. These particular dates were passed down from generation to generation as impure days when the mountains were unsafe for humans. The villagers of Kōchi would warn each other not to venture deep into the forests or provoke spirits and demons on those days. These were not superstitions taken lightly—for many, they were rules as sacred as religious prohibitions.

The best-known story related to warai onna is the tale of the samurai Higuchi Kandayū, which has gained the status of a regional cautionary legend. Kandayū, having ignored the villagers’ warnings, set out on a hunting trip in the mountains of Tōkōzan (東光山) with his companions—on the ninth day of the month, no less. On a forest path, he encountered a young woman whose beauty was exceptional. She smiled and began to laugh—first gently, then louder and louder, until the laughter became an all-encompassing sound that filled his entire head, his entire world. Kandayū experienced something he couldn’t explain—he had the sensation that the entire mountain was laughing at him. Trees, rocks, the river, even the wind—all took on the mocking tone of that same terrifying laughter.

Stories of warai onna have survived in local folklore in other towns of Kōchi, such as Sukumo, Tosayama, and Kagamimachi. They differ in details, but one element is always shared—the presence of a mysterious woman, laughter that offers no peace, and death that comes not from a blade, but from laughter.

Where and When Can You Encounter Warai Onna?

Where?

The mountainous regions of Kōchi Prefecture (高知県)—in many areas of this prefecture, especially those surrounded by dense forests and steep slopes, stories have been passed down about places where warai onna regularly appears. These are primarily wild, rarely traveled mountain paths. In towns like Sukumo, Tosayama, and Kagamimachi, encounters with this yōkai are also mentioned—often in the form of elusive laughter echoing through the night.

When Should You Avoid the Mountains?

These dates were passed down as "impure days," when one should not enter the mountains, chop wood, hunt, or travel alone. It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly why these days were considered special, but researchers point to several possible reasons for their selection.

Relation to the Lunar Calendar:

The 1st, 9th, and 17th days correspond roughly to the new moon, first quarter, and (almost) full moon—transitional phases when the spiritual world was believed to have the most influence over the human world. It was thought that during these times, the boundary between reality and the afterlife became blurred.

Number Symbolism in Japanese Culture (perhaps a bit speculative, but such interpretations do exist):

Number Symbolism in Japanese Culture (perhaps a bit speculative, but such interpretations do exist):

1 – beginning, birth, but also loneliness and unpredictability.

9 (kyū) – phonetically resembles the word 苦 (ku) – “suffering”; considered an unlucky number.

17 – a compound number that symbolically might suggest chaos (1 + 7 = 8, and eight in tradition can imply “expansion” or “spreading,” such as that of madness or a curse).

Practical Folk Considerations:

In some regions, these days—due to lunar phases—may have coincided with periods of fog, dark nights, or other treacherous terrain conditions, making them dangerous for travelers. The legend of warai onna may have served as a symbolic warning encoded in the form of a ghost story.

Are any of these explanations true? Or could there be another, better reason? At this point, I haven’t been able to determine that.

Laughter in Japanese Culture

In nō theater, the smiling woman’s mask—ko-omote—was often used for tragic, haunted characters torn from within. The laughter of such a figure was not the laughter of happiness—but a smile that concealed suffering or revealed madness. The Japanese language even contains the expression 「笑いながら泣く」 (warai nagara naku) — “to cry while laughing” (an expression also found in European languages, including Polish), pointing to the emotional dissonance so frequently explored in Japanese art.

I

In everyday life, Japanese people often use laughter as a tool of politeness, social distancing, or protective masking. Laughter can cover embarrassment (terewarai, 照れ笑い), ease tension, or avoid direct confrontation. But in this socially conditioned form lies a shadow—because laughter becomes a duty, a learned gesture, sometimes mechanical. In its extreme form—as in warai onna—it can resemble an empty form that overrides the workings of reason.

Finally, in Japanese aesthetics, rooted in concepts like honne and tatemae (true feelings versus social facade), laughter can be a mask for the deepest loneliness. The smile we wear on our face is not always a reflection of what’s happening inside. Warai onna doesn’t attack with a scream—she attacks with laughter. For that very laughter becomes a symbol of the erosion of the boundary between truth and illusion, between calm and chaos, between the world of the living and the world of spirits.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Tanuki Swinging His Coin Pouch – How Did Japanese Woodblock Artists See This Rascal?

Poetry with Sake – Master Senryū and His Joyfully Malicious Insight

Haikyō Onsen – Japanese “urbex” amid the abandoned beauty of 1980s resorts

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Number Symbolism in Japanese Culture (perhaps a bit speculative, but such interpretations do exist):

Number Symbolism in Japanese Culture (perhaps a bit speculative, but such interpretations do exist):