The Mountain Witch Yamanba – Feminine Wildness That Terrified the Patriarchal Men of Traditional Japan

A Shadow in the Mountain Forests

How to Understand the Name?

Yamanba

▫ 山婆 (yamanba) – using the character 婆, more directly evoking a witch or crone.

▫ 山母 (yamaha/yanbō) – “mountain mother,” a form emphasizing her archetypal, matronly roots.

▫ 山姫 (yamahime) – “mountain princess” — a figure from older traditions: younger, sometimes divine.

▫ 山女郎 (yamajoro) – “woman of the mountains” or “mountain courtesan,” with a more ambivalent connotation, close to folk tales of supernatural seductresses.

The History of the Concept

The History of the Concept

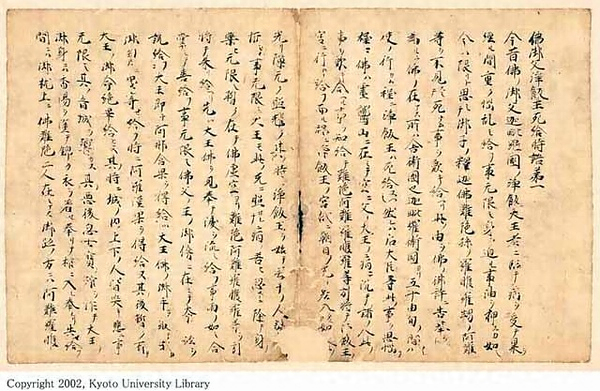

The figure of Yamanba appears as early as in classical collections of folk tales from the Heian and Kamakura periods. One of the oldest written references can be found in Konjaku Monogatari (今昔物語集, late 11th to early 12th century) — an anthology of legends from Japan, India, and China that preserved many original motifs. In later eras, her image appears in story collections such as Otogizōshi (御伽草子) — short, illustrated Muromachi-period tales often containing moral or metaphysical messages.

What Was the Yamanba Witch in Japanese Imagination?

Yamanba appears at the crossroads of myth and daily life, between dream and reality, at the meeting point of the feminine, the wild, and the untamed. She was a liminal figure — belonging partly to the human world, and partly to the supernatural. Though her name changed by region and her face was never quite the same, her presence was eerily familiar to anyone raised at the foot of Japan’s mountains.

Appearance: A Woman of Mist and Shadow

Appearance: A Woman of Mist and Shadow

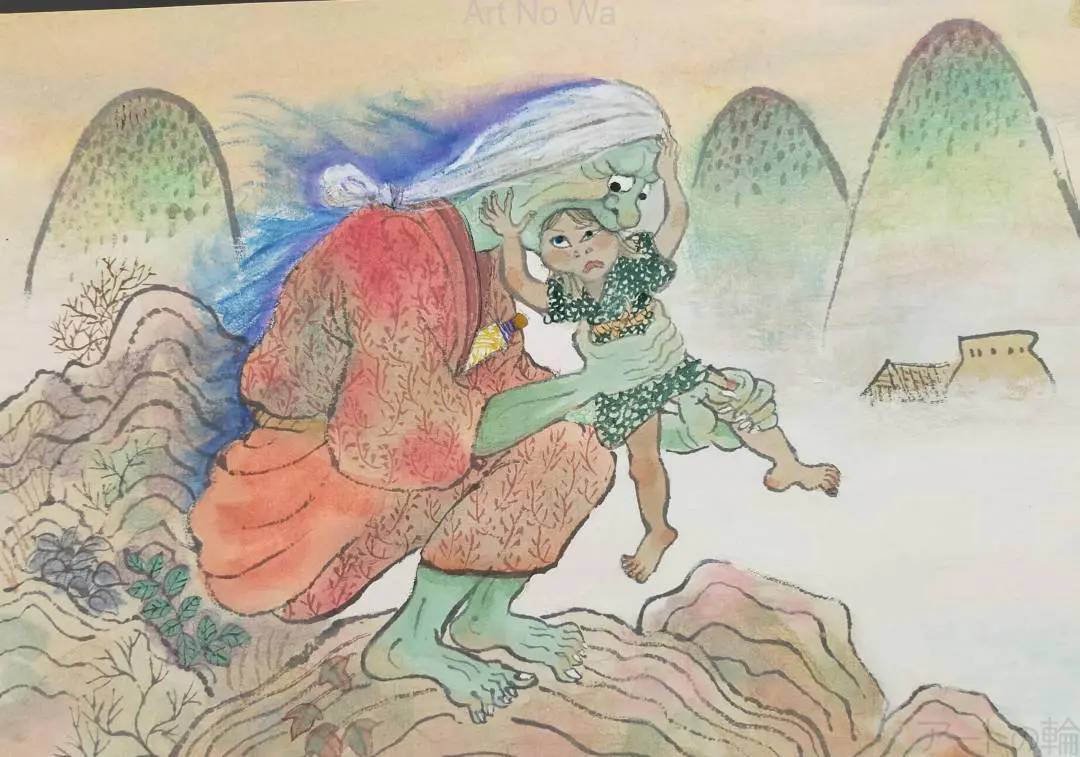

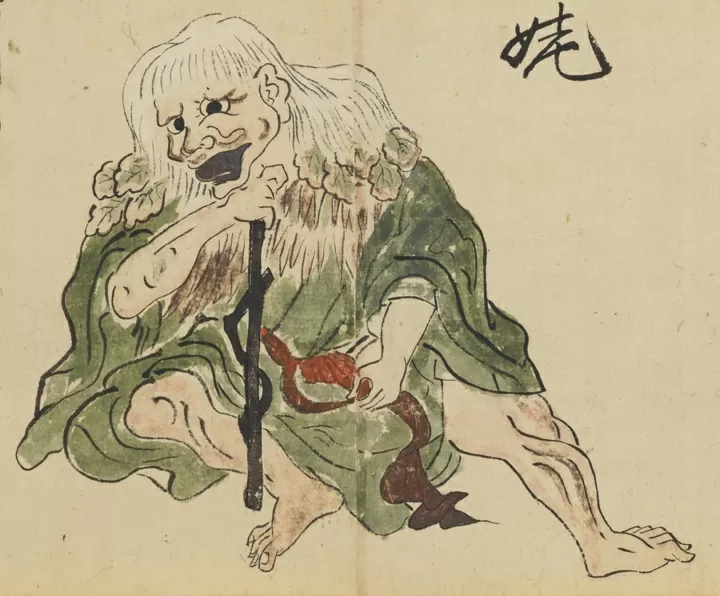

Yamanba may take the form of a gentle old woman with a warm gaze and work-worn hands. She is the one who invites a shivering traveler into her hut, offers him hot soup made from forest roots, and warms his bedding. But at night, her smile changes — her mouth opens into a gaping maw from ear to ear, her eyes ignite with fire, and her long, white hair bristles unnaturally.

In classical woodblock prints and folk tales, Yamanba’s metamorphosis is a constant element. She can be a beautiful girl singing among the mosses, and moments later turn into a terrifying figure. In the darkness, she transforms from a hospitable hostess into a monster. In some versions of the folk legends, she can fly, suck blood, take the form of a spider, or vanish like smoke when someone tries to harm her.

Duality: Mother and Monster

Duality: Mother and Monster

What is most fascinating about Yamanba is her inner contradiction. She can be both a nurturing mother and a devourer of humans. In tales from Nagano Prefecture, she saves children lost in the forest, feeds them milk, and cradles them to sleep. But in other stories, one hears the sound of a knife being sharpened at night — and then it is clear that the traveler who accepted her hospitality will not live to see the morning.

Her fertility is also legendary — in some stories, it is enough for her to touch a man to become pregnant and bear hundreds of children. In the myth of the birth of Kintarō, the future warrior Minamoto no Yorimitsu, Yamanba gives birth to a son from a divine dream, after an encounter with a red dragon. She is thus not merely a monster — she is the mother of a hero, a priestess of life.

In What Stories Does She Appear?

In the fairy tale Nukafuku and Komefuku, Yamanba rewards the good, humble sister and punishes the bad and greedy one — showing that although she can be harsh, she is also just and tied to an ancient moral order. In other versions, she brings luck and wealth to the family she chooses — if she is not rejected, she may even become a household deity.

Ties to Reality: Hunger and Exclusion

Ties to Reality: Hunger and Exclusion

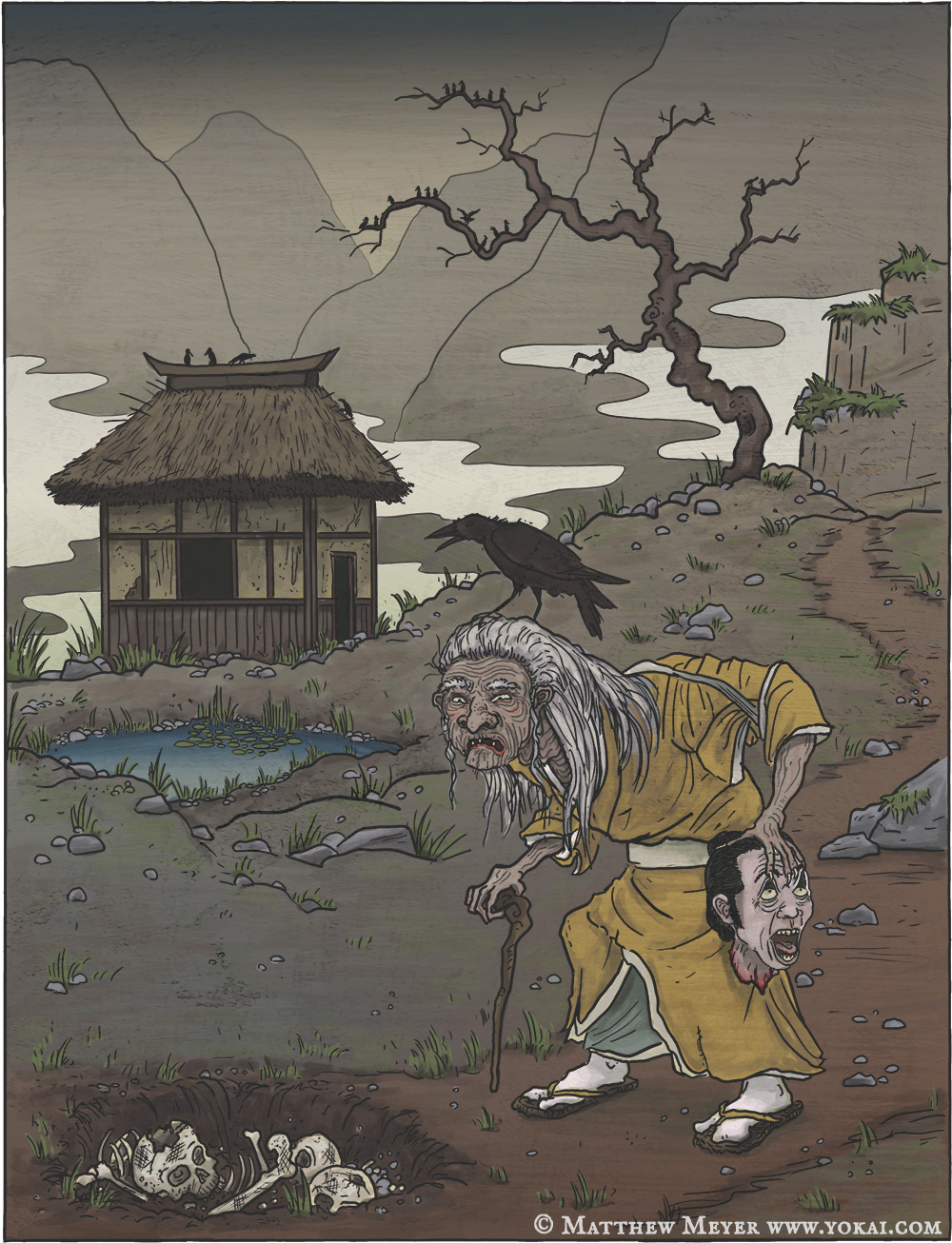

Behind the legends of Yamanba lies not only archetypal power but also a painful social truth. In times of famine and poverty, when there was not enough food for everyone, there existed a tale of a custom called ubasute — the abandonment of elderly women in the mountains to die alone. These women — cast off by loved ones, stripped of their role as mothers and as human beings — could become Yamanbas. Born of hunger, of pain, of rage. Or perhaps of a desire for revenge.

(Note: this is a common motif in both painting and literature as a cautionary tale — interestingly, there is currently no concrete evidence that ubasute was ever actually practiced.)

Yamanba is not a one-dimensional monster. She is a reflection of collective fear and collective memory — of old age, wildness, and feminine power. And if we try to find a common thread running through all the stories about her, it seems to be this: the fear of men. The fear of the patriarchal order in the face of a woman who is independent of men. Let us examine this more closely.

The Archetype of the Wild Woman and Patriarchal Fear

The Archetype of the Wild Woman and Patriarchal Fear

In myths, as in dreams, what is repressed returns in the form of terror. Yamanba — the old woman from the mountains, sometimes wild, sometimes nurturing — is not merely a folkloric specter, but an archetype of the woman whom the male world has failed to subdue. Her figure emerged from a deep cultural need to tame, ridicule, or destroy what cannot be controlled — the unpredictability of the female body, its cycles, its connection to nature and death. In this sense, Yamanba is not only a character from legend — she is a vessel for stories about male fear and female power.

The Female Body as a Political Site

Over time, this mistrust of the female body turned into ideology. The ancient goddess of fertility — she who gave life and gathered the harvest — was transformed into a witch, a crone, a devourer of children. Yamanba is one of the most poignant symbols of this transformation: on the one hand, she gives life and milk; on the other — she devours and destroys. She is the projection of fear of feminine autonomy, of the idea that a woman might exist independently — of man, of the household, of the system.

Yamanba as the Embodiment of Feminine Power

Yamanba is also situated close to the great female deities of Japan. Izanami, the mother of the world, who dies giving birth to the fire god and becomes the first undead (more about her here: The Tragedy of Izanami and the Fury of Izanagi in the Land of Decay – In Japanese Creation Myths, Death Always Wins). Ōgetsuhime, the goddess of food, who after death gives rice, grain, and silkworms from her own body. Like them, Yamanba unites life with decay, creation with destruction. In legends, her milk and excrement turn into magical spices, her body — into medicine, her death — into a new beginning. This is organic femininity, rooted in the earth, ambivalent — far from idealized, “pure” visions.

A Figure of Resistance: A Woman Outside the Home, Outside the Norm

A Figure of Resistance: A Woman Outside the Home, Outside the Norm

Yamanba is also a woman who left her home — both literally and symbolically. In traditional Japanese society, the woman was tied to the interior space: the home, the kitchen, the private realm. A woman who wandered the mountains, unmarried, old, and alone, became a suspicious figure — potentially dangerous. If she also possessed knowledge (herbal, ritual, bodily), she became something more: a threat to the order.

This is precisely what Yamanba is — a figure of resistance against the norm. She does not wish to be a mother or a wife. She does not serve. She does not pray. She does not purify her body according to rules made by men. Her mere existence challenges the patriarchal structure of the world. That is why she must be punished: through death, demonization, or “folklorization.” But even as a monster — she survived.

Yamanba and Her European Sisters: Medusa and Medea

In patriarchal culture, a woman who knows becomes a witch; a woman who wanders becomes a sorceress; a woman who lives beyond control becomes a monster. But perhaps it is precisely from these figures — from Yamanba, Medusa, Medea — that the possibility of another kind of femininity emerges: wild, untamed, creative, unpredictable. One that does not ask for permission but simply exists.

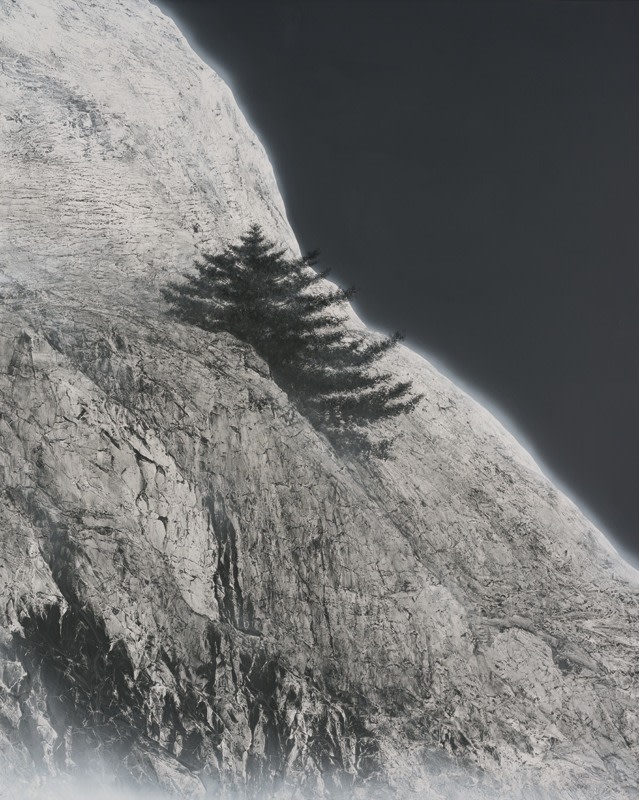

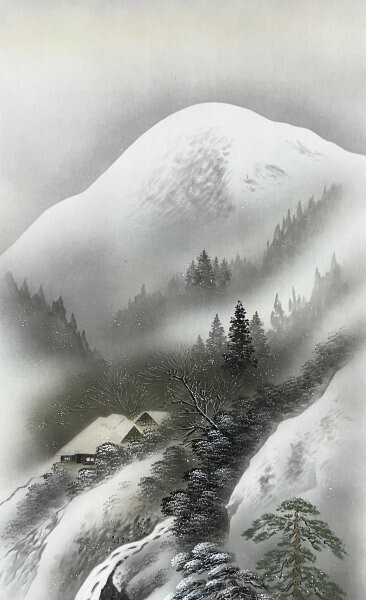

The Symbolism of Mountains as a Liminal Space

In the Japanese imagination, mountains are not merely scenic backdrops — they are living entities, pulsing with mystery, full of invisible presences where earth meets sky and the world of humans intermingles with that which is beyond human. Where the village ends and the wall of forest begins, another order arises — wild, unpredictable, deeply spiritual.

That is where Yamanba dwells.

The Mountain as a Liminal Space

That is precisely why so many stories about Yamanba take place in the mountains. It is there that she is encountered by chance; it is there one comes to abandon someone who can no longer be kept alive. It is there that a woman can disappear — and return as something new. In Japan, the mountain is not a boundary but a zone of suspension — a place where one may strike a pact with a spirit, marry a dragon, give birth to a divine child, or perish in the jaws of a witch.

Yamanba as a Mountain Spirit

Yamanba as a Mountain Spirit

In this landscape, Yamanba is not merely a monster. She is the spirit of the mountain — the embodiment of what is wild, unpredictable, but also nurturing and cyclical. In some versions of the tales, she appears as the protector of lost children, brings fortune to the household that welcomes her, and teaches people to gather herbs and understand the rhythms of the forest. In others — like the seasons — she brings death and cold. She is the living reflection of the mountain’s nature: beautiful and dangerous, fertile and destructive, accessible and inaccessible all at once.

In folk traditions, many mountains had their own deities — yama no kami, gods of the forests and peaks. Yamanba is the feminine incarnation of that force, its sensual, corporeal aspect. Where yama no kami was often a male figure associated with hunting or fishing, Yamanba became the mistress of herbs, fire, fertility, and rain — a being closer to earth, to the body, to childbirth, to the lunar cycles.

Inspirations from Mountain Spirituality

Inspirations from Mountain Spirituality

In the figure of Yamanba, echoes of Shugendō can also be heard — a syncretic system of mountain asceticism blending elements of Buddhism, shintō, and local beliefs. Practitioners of Shugendō — yamabushi — believed that only through solitude, suffering, and contact with the mountain could one attain spiritual awakening. The body was, for them, a tool of transformation, and the mountain — a living organism that taught, punished, and blessed.

Yamanba resembles a female yamabushi — a wandering priestess who carries not incense but herbs, not prayers but laughter, rage, and the cry of childbirth. She is a figure outside temples and monasteries, yet profoundly religious. Her religiosity is a mysticism of rain and milk, of communion with the rhythm of mountain life, of knowledge passed through roots and stones, not through sutras.

In this way, the mountain becomes not merely the backdrop for Yamanba, but her very body. One cannot understand her figure without understanding the Japanese reverence for the landscape and the belief that every place — every tree, spring, and stone — possesses its own spirit. Yamanba is a feminine, wild, elusive spirit — dwelling in spaces that cannot be fenced in, named, or subdued.

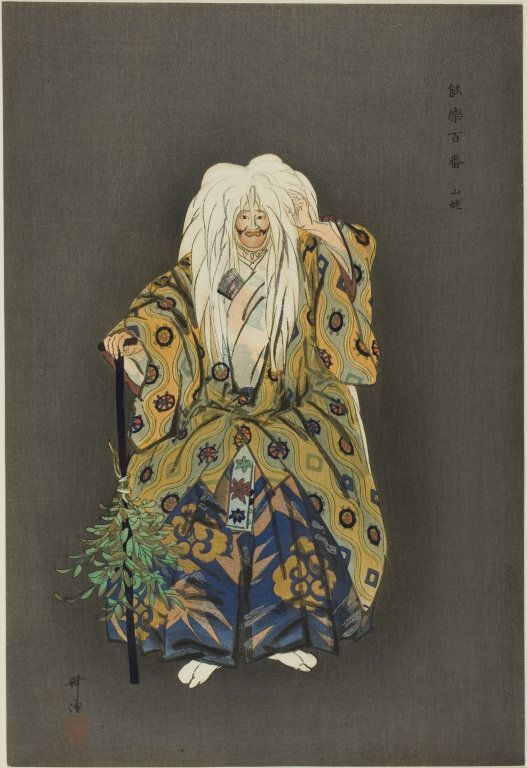

- a Nō Play by Zeami Motokiyo, 15th Century

At this point in our journey with Yamanba, it is time to take a step further — from folklore to art, from myth to philosophy. One of the deepest and most moving representations of this figure in Japanese culture is the classical nō play Yamanba (also spelled Yamamba in older readings), attributed to Zeami, the father of nō theatre. This work not only reinterprets the legend of the mountain witch — it distills it into a philosophical meditation, in which every syllable, every gesture, every sound becomes a gateway to the invisible world. Nō theatre is one of the branches of Japanese art that is most difficult for us foreigners to grasp — its content is not easily accessible, though it is profoundly and quintessentially Japanese in expression. Let us attempt, then…

The Plot

The Plot

At the center of the story stands Hyakuma-Yamanba — a famous dancer from Kyoto who has created the renowned kusemai dance depicting the mountain witch. During a pilgrimage to the temple Zenkō-ji, accompanied by her entourage, the artist arrives in a mountain village where, in a strange, symbolic twilight, time comes to a halt and the sun sets unnaturally early. An old woman appears — gentle, yet strange — who invites them into her hut. She asks Hyakuma-Yamanba to dance for her — because it is to her, the real Yamanba, that the dancer owes her fame.

When night falls and the moon rises, reality comes to a standstill. The true Yamanba returns in her authentic form — as a spirit, a being beyond human duality of good and evil. She dances with Hyakuma-Yamanba, binding her fate to that of the artist and revealing the secrets of life and illusion.

Displacement of Time and the Dance

Displacement of Time and the Dance

One of the most striking elements of the play is the symbolic disruption of time. When Yamanba “draws down” twilight earlier than it should come, she violates the order of the world, suggesting that the visible world — the one in which day follows night — is merely a projection. True reality unfolds beyond linear time, in a dimension where spirits dwell, thoughts are alive, and truth resides.

In this reality, dance becomes a language between worlds. It is not an aesthetic form — it is a tool of revelation. When Hyakuma-Yamanba plays the flute and the wind in the pines answers her notes, a unity is achieved between artist and mountain, between human and nature. The shared dance of the two Yamanbas — one corporeal, the other spiritual — becomes a ritual uniting the two shores of existence. Their movements resemble falling plum blossoms, and the water in the mountain stream reflects the moon like a mirror of consciousness, as the play’s song proclaims.

The Philosophical Meaning of the Play

The Philosophical Meaning of the Play

Yamanba, in Zeami’s interpretation, is no longer merely a character from legend — she is a figure of Buddhist wisdom, the embodiment of the illusory world of samsara. Her words are full of paradoxes: she says the valley is the depth of the Buddha’s compassion, and the mountain peaks are his heart. She argues that good and evil are illusions of the mind, that suffering and wandering are part of the path to enlightenment.

Yamanba no longer demands sacrifices — she teaches empathy. She speaks of awakening through journeying, of a “circular” life — returning, cyclical, ever winding along the slopes of existence. Her tale is a parable of transmigration of souls, of the eternal wandering of consciousness, of losing oneself in order to be found again. In this sense, Yamanba resembles zen masters — she does not speak directly, teaches through paradox, guides through shadow.

Yamanba as the Wisdom of Nature and Emptiness

Yamanba as the Wisdom of Nature and Emptiness

If the mountain is a liminal space, and the woman a figure of transformation, then Yamanba unites both extremes. She lives “outside,” but also “within” — within life and death, purity and defilement, in the mist that cannot be grasped. She says her existence is an illusion — but couldn’t the same be said of ourselves? — she asks at the end of the dance.

When she disappears, she asks only one thing: to be remembered. That in the dance, which seems to serve only entertainment, one might find a trace of truth. To not forget that life is a circle, not a line — that wandering through the mountains is our shared condition. For each of us carries a fragment of Yamanba within — she who knows that only those who have lost their way have a chance to awaken.

Contemporary Reincarnations of Yamanba

From Mountain Witch to Icon of Urban Rebellion

Although Yamanba as a folkloric figure was born in the shadows of mountain paths, her spirit has survived not only in fairy tales — it has been reborn in the most unexpected spaces of contemporary Japanese culture. Not in temples or nō theatres, but on the streets of Shibuya, in street fashion, feminist art, and literature. She has become a figure of female defiance — shifting, wild, impossible to categorize. Just as she once frightened with her ambiguity, today she fascinates as a symbol of resistance to roles imposed on women, to prescribed sexual aesthetics, and to the broader male order.

Yamanba as a Pop-Cultural Symbol

The most visible and surprising incarnation of Yamanba in modern times was undoubtedly the yamanba-gyaru style — a fashion subculture that flourished in the 1990s and 2000s on the streets of Tokyo, especially at the Shibuya crossing and in Harajuku (you can read much more about this in the book "Silne kobiety Japonii" (only in Polish)). Young girls — usually teenagers and women in early adulthood — crafted an extremely exaggerated appearance: bodies tanned to the extreme, platinum or pink hair, white or fluorescent makeup around the eyes, false lashes, platform shoes, and flashy clothing.

Scholar Laura Miller, author of Beauty Up: Exploring Contemporary Japanese Body Aesthetics, notes that the yamanba style was a form of bodily inscription of rebellion — women wrote on their bodies a history of dissent, rejection, and affirmation of otherness. It was aesthetic resistance that — just like Yamanba — evoked both fear and fascination.

Yamanba in Contemporary Literature and Art

Yamanba in Contemporary Literature and Art

In contemporary literature and art, the figure of Yamanba is experiencing a renaissance as an archetypal, feminist, and countercultural symbol. In the works of writers such as Kurahashi Yumiko and Ogawa Yōko, echoes of Yamanba emerge as a woman on the edge, one who transcends the conventions of body, gender, and morality. Kurahashi, in her novellas, creates female characters who are terrifying yet compassionate — isolated, but undefeated. Similarly, Hiromi Itō, a poet who weaves together corporeality, motherhood, and spiritual wildness, often evokes metaphors of witches, crones, and mountain spirits.

In the visual arts, Yamanba reappears in the work of artists such as Miwa Yanagi, whose photo series My Grandmothers and cycle Yamauba and the Young Girl depict older women as strong, wild, rebellious — freed from the roles of nurturing mother or sexual object. Yanagi portrays them as transgressive figures, straddling the real and the fantastical — precisely as Zeami did in nō theatre.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Yamanba resists easy definition. In every era, in every story, she takes on a different face: at times she nourishes and protects, at others she devours; sometimes she teaches, other times she vanishes, leaving only a trace in the snow. She is a mother, a goddess, a witch, a demon, a sage, sometimes merely a shadow against the mountain. But perhaps it is precisely in this mutability that her power lies — Yamanba does not want to be just one thing. She reminds us that a woman — like a mountain — can be unpredictable, difficult to tame, and full of a force that defies categorization.

Her story has not disappeared. It continues to return — in nō theatre, in subcultures, in poetry, in urban makeup, in the literary monologue of a witch who no longer wishes to apologize for who she is. In an era when the female body remains an object of fear, judgment, and control, Yamanba becomes a figure of resistance — of what is wild, old, un-aesthetic, but true and free. Her ugliness — as contemporary feminists have written — is a strategy of emancipation; her wildness — a reminder of what has been repressed by patriarchal culture.

And at the end of this article, let us not fall into Western self-admiration over how far we’ve come in shedding patriarchal ways of thinking. I offer an image. On the left: a modern Japanese yamanba. On the right: a sculpture by Swedish artist Anna Udenberg titled Monument to the New Generation, a representative of the dominant social media aesthetic of Western civilization.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

The Female Samurai Unit Jōshitai – The Ultimate Determination of Fighting Mothers and Sisters

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The History of the Concept

The History of the Concept Appearance: A Woman of Mist and Shadow

Appearance: A Woman of Mist and Shadow Duality: Mother and Monster

Duality: Mother and Monster Ties to Reality: Hunger and Exclusion

Ties to Reality: Hunger and Exclusion The Archetype of the Wild Woman and Patriarchal Fear

The Archetype of the Wild Woman and Patriarchal Fear A Figure of Resistance: A Woman Outside the Home, Outside the Norm

A Figure of Resistance: A Woman Outside the Home, Outside the Norm Yamanba as a Mountain Spirit

Yamanba as a Mountain Spirit Inspirations from Mountain Spirituality

Inspirations from Mountain Spirituality The Plot

The Plot Displacement of Time and the Dance

Displacement of Time and the Dance The Philosophical Meaning of the Play

The Philosophical Meaning of the Play Yamanba as the Wisdom of Nature and Emptiness

Yamanba as the Wisdom of Nature and Emptiness Yamanba in Contemporary Literature and Art

Yamanba in Contemporary Literature and Art Conclusion

Conclusion