Inugami – The Dog to Whom Loyalty Was Repaid with Betrayal and Cruel Death. How Do Japanese Yōkai Portray Generational Family Trauma?

Colorful Little Monsters Not So Pastel After All

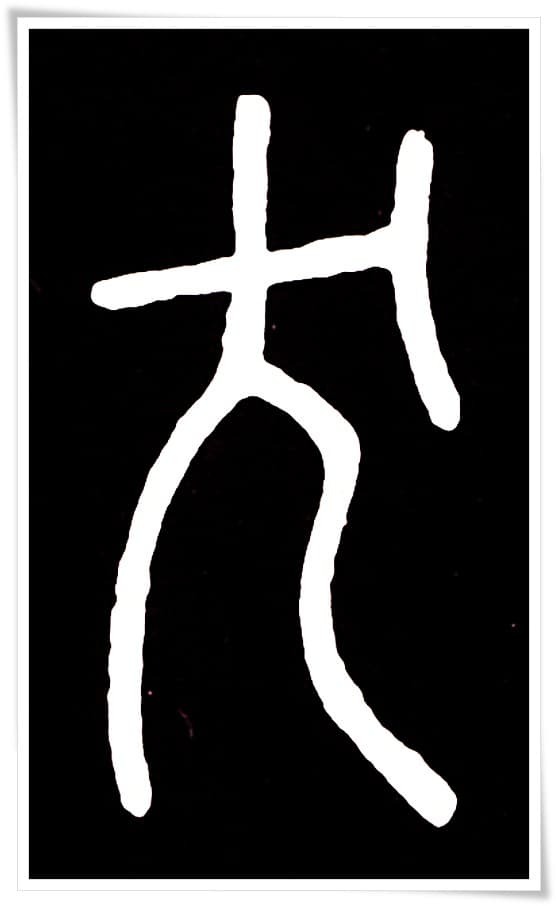

Etymology and Meaning of the Word 犬神

(犬 – inu, “dog” + 神 – kami, “god, spirit, divinity”)

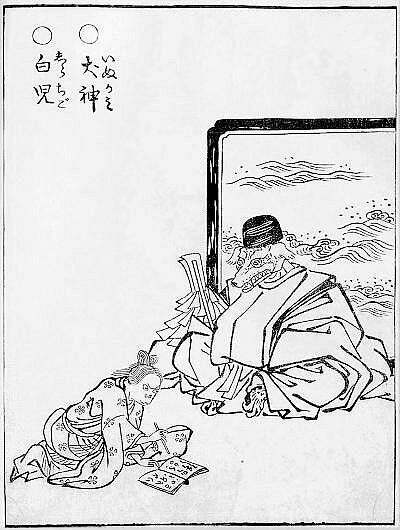

In ancient writings, other forms of the word appear as well: 狗神, where 狗 (read as ku or inu) is an archaic character also meaning dog, but with a slightly more pejorative, “wild” nuance. Inugami written in this way suggests not a gentle human companion, but an untamed force of nature, a dog not yet domesticated. Other regional phonetic variants, such as ingami or irigami, testify to how deeply and diversely the concept took root in the folk speech of western Japan—particularly in the prefectures of Shikoku, Ōita, Kumamoto, or Yakushima. In Tanegashima, they are called irigami, and in Yamaguchi, even inugami-nezumi, or “rat-like inugami.” These variants indicate that inugami was not a single, fixed entity, but an entire continuum of local imaginings of dog spirits—from beasts to powerful, divine beings.

Linguistically, it is also worth examining the grammatical position of kami in such compounds. The character 神 can refer to both a specific god (e.g., 天照大神 – Amaterasu-ōmikami) and a spirit in the broader sense—not necessarily benevolent. In terms like yama no kami (mountain god) or ie no kami (household deity), kami is a local force, attached to a particular space. Inugami can thus be understood as the spirit of a dog that has bonded with a home, a clan, a bloodline—but with a power greater than that of an ordinary animal spirit. It is not just a dog as an animal, but a dog as tsukimono—a being that enters into a relationship, brings possession, protects or destroys.

From a linguistic standpoint, one more detail is worth noting: the compound 犬神 formally resembles many names of local kami (such as kitsune-gami, kuda-gitsune, osaki-gami), yet only inugami has achieved a status so deeply entrenched in social and cultural taboo. In Japanese consciousness, the dog was not associated with divinity to the same degree as the fox, snake, or boar—thus inugami seems to be a breach, a disturbing anomaly, something that never should have been sanctified—and yet was, through suffering and death.

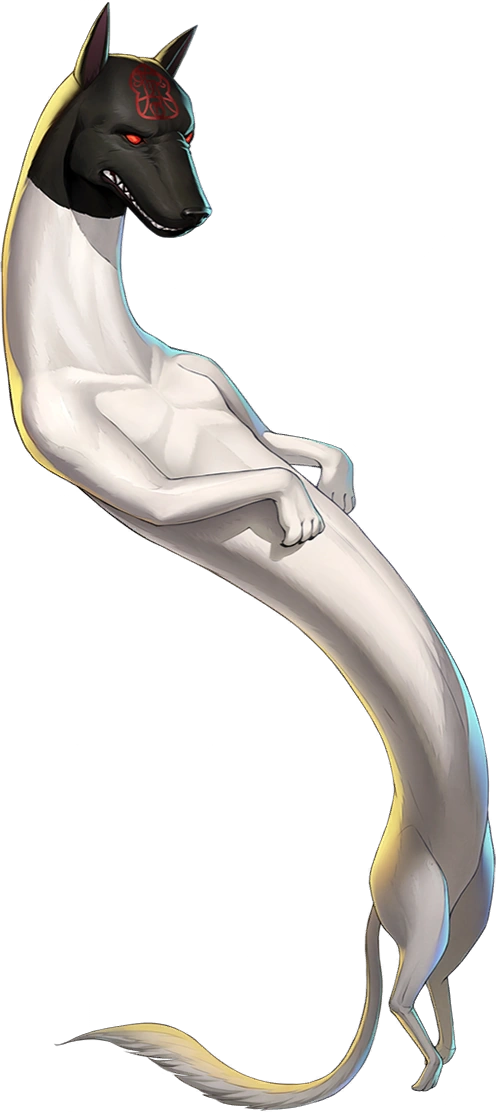

The archetypal inugami evokes many intense emotions: loyalty unto death, rage over disgraceful betrayal, the sorrow of rejection, and also the thirst for revenge. In this sense, inugami resembles more an “angel” of wrath than a serene deity—a spirit born of both love and violence, one that carries within it the echo of a loyal dog and a relentless avenger.

When juxtaposed with Western concepts of spirituality, inugami defies easy classification. It is neither a demon nor a guardian angel. It is the Japanese response to the question: what happens when loyalty is answered with betrayal? When a dog—the most faithful of beings—is driven to death (in torment), and behind its suffering stands a human—the very one to whom the dog had been devoted beyond its life?

That is precisely what inugami is—the divine dog that never ceases to hear the footsteps of its master. Even after death.

How Is an Inugami Born? Rituals of Hunger, Pain, and Desperation

The inugami is not a being spontaneously born, like some other yōkai. It is a spirit created deliberately—ritually, consciously, with the intent of harnessing its power. And that is precisely why it is so dangerous. It does not come from nature. It is the product of pain, hunger, and human desire to control the invisible. It is not a natural yōkai, a colorful inhabitant of the supernatural realm. It is a human "creation"—intentional, calculated, and cruel.

The most well-known method of "creating" an inugami involved imprisoning a dog and driving it to utter desperation. Often, the animal was tied in such a way that it could not reach a bowl of food—always close, but always just out of reach. In another version, the dog was buried alive, with only its head left above the ground. Food was placed in front of its muzzle. When the moment of greatest hunger and desperation came—the head was severed. It was believed that in that instant, the dog’s spirit, filled with pain and rage, became an onryō—a vengeful ghost capable of interfering in the world of the living.

All of these practices had one goal: to create a spirit that would be loyal but furious, ready to obey commands, yet filled with the memory of suffering. The dog’s head—often mummified, dried, or charred—was then kept in a special vessel, which became a fetish, a home for the inugami. Such an "artifact" was kept hidden—under the floorboards, in closets, chests, or water jars. It was a spiritual weapon, inherited from generation to generation.

One cannot help but notice the similarities to the practices of kodoku (蠱毒)—the esoteric art of curse-making known in China and Japan. Kodoku involved sealing numerous poisonous creatures (such as snakes, toads, and insects) in a jar until they devoured one another. The last survivor became the source of toxic power—its venom used to craft curses. The inugami is a different, nightmarish version of kodoku—but in this case, the victim is a dog, and the goal is not poison but a spiritual emissary.

These rituals were also linked with onmyōdō (陰陽道)—a syncretic divinatory-magical-religious system drawing from Taoism, esoteric Buddhism, and Shintō (for more on the legendary representative of this Japanese sorcery—Abe no Seimei—read here: The Sorcerer at the Heian Emperor's Court: Abe no Seimei, Master of Onmyōdō). Although officially banned during the Heian period (794–1185), the practices associated with inugami creation survived in folk onmyōdō, practiced by fuko (巫覡)—village sorcerers and shamans—as well as by yamabushi—mountain ascetics—and miko (about whom more can be read here: Shinto Priestess Miko – From Powerful Shaman to Part-Time Work). It was believed that only individuals with the appropriate spiritual power and knowledge of the ritual could subdue the spirit of the inugami—and make it a loyal instrument.

Today, these stories evoke horror—not only because of what they describe, but because of their logic. It is suffering as a method of attaining power, an emotion pushed to the limits—and then trapped in a vessel and passed on. The inugami is not merely a dog spirit. It is the shadow of humanity that permits loyalty to be exploited, and pain to be transformed into a tool for dominion over life and death. It is the most drastic form of exploiting another being—its weakness, even its virtues—for the satisfaction of one’s own ends. It is not easy to find in the entirety of Japanese culture examples that rival these beliefs in sheer cruelty.

Inugami-tsuki – Possession by the Dog Spirit

Possession by an inugami took many forms, but all shared a common feature: the spirit did not manifest suddenly or spectacularly. On the contrary—it entered unnoticed, through the ear. This detail is deeply symbolic in itself. In Japanese folklore, the ear is often seen as a gateway for invisible entities, as it represents the most passive of the senses—the one that absorbs things without filter. The inugami needs no invitation—all it takes is a moment of inattention, a lapse of emotional strength, a moment of vulnerability.

In this way, possession also became a metaphor for psychological instability, transformed into the language of spirit. Traditional Japanese folk knowledge lacked the Western concept of psychosomatic disorders, but it was able to name and describe them through images of spirits that feed on anger, anxiety, envy—and at the same time, intensify them.

Significantly, the inugami did not limit itself to humans. It was believed to be capable of possessing livestock—horses, cattle—as well as everyday tools, such as saws, which when possessed became either useless or… worse. In one local version of the story from Tanegashima, the spirit could transfer through touch, or even… through shared food. There was a practice called inugami-tsure ("taking the inugami with you"), which involved leaving food in the home of someone suspected of harboring an inugami—in the hope that the spirit could be bribed and would leave with the offering.

In some cases, after the death of a possessed person, bite and claw marks were found on the body—interpreted as a final act of vengeance or an enduring bond between the spirit and the flesh.

Inugami Families – A Cursed Legacy

Belief in inugami-suji carried significant social consequences. Chief among them—inheritance. It was believed that the inugami spirit did not vanish with the death of its owner—it passed on to the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. If someone married into such a family, they too could become “infected” with possession, and the spirit could transfer to their household. For this reason, in many regions of Japan—especially in Shikoku and Kyūshū—when arranging marriages, family lineages were examined, elders were questioned, and rumors were investigated. Coming from an inugami bloodline could ruin an entire life—not just for one individual, but for their entire line.

Thus emerged mechanisms of social exclusion—this was a very real and significant phenomenon, regardless of whether the inugami truly existed or not. Contemporary research into this phenomenon indicates that many families labeled as inugami-mochi belonged to socially marginalized groups, often associated with the burakumin, the former "untouchable" caste. This issue is linked to dōwa mondai—a complex system of discrimination that persisted well into the 20th century (and in some aspects still exists in hidden form today).

Social ambivalence toward these families ran deep: on one hand, they were feared and despised; on the other, sought after when curses, revenge, or spiritual intervention were needed. This double tension—reverence and stigmatization—created a tangled web of unclear relations between village society and the spirit world. Sorcerers and miko were simultaneously outcasts and intermediaries with the other world. Families with inugami were treated as sources of power—but it was a power to be kept at a distance.

In some folktales, such as those from Komatsu in the old province of Tosa, the number of inugami was said to equal the number of family members. Each person received their own spirit—just as others might receive a name or a dowry. These spirits “understood without words”—a mere thought or desire from a family member was enough to send the inugami on a mission. But they were not entirely docile spirits. In the legends, there were cases where an inugami bit its own master to death—if it deemed them unworthy.

This inheritance—not of blood, but of emotion, guilt, and fear—makes the inugami not just a supernatural being, but also a metaphor for family trauma passed down from generation to generation, still present beneath the surface of everyday life. A spirit that endures because no one has been able to bury it—or truly love it.

Inugami as Kami – Loyalty, Revenge, and Unpredictability

The mystery of the inugami lay in its unpredictability. Unlike the typically gentle deities of shintō, a relationship with an inugami was never safe. It remembered too much. Its loyalty, though absolute, carried the shadow of trauma. It is precisely this contradiction—between protection and threat—that made it so unique and unsettling. In many folk accounts, it is noted that an inugami can serve for generations… but if neglected, forgotten, or dishonored, it will turn against the household and bring death, madness, or ruin.

The boundary between worship and subjugation is especially significant here. The cult of inugami was not a spontaneous act of faith, but a form of control over pain and fear. It was venerated not because it was “holy,” but because it was powerful—and vindictive. This is a different dimension of religiosity than that of Japan’s official shrines: a private, emotional religion based on a bond that was never free of violence.

Symbolically, inugami may be read as the figure of the inverted house dog—the one that does not lie at its master’s feet, but instead lurks in his soul. It is a metaphor for the master–servant, dog–human relationship in which loyalty is wounded and then transformed into a tool. In this sense, inugami also becomes a metaphor for toxic bonds: those of family, emotion, or work—relationships in which loyalty and submission are rewarded only for a time. And then—punished.

In the context of Japanese culture, where loyalty (chūgi 忠義) was for centuries a fundamental value—especially in the samurai ethos—inugami is a dark perversion of that virtue. It shows what happens when virtue is used for violence—when the dog that loved is betrayed.

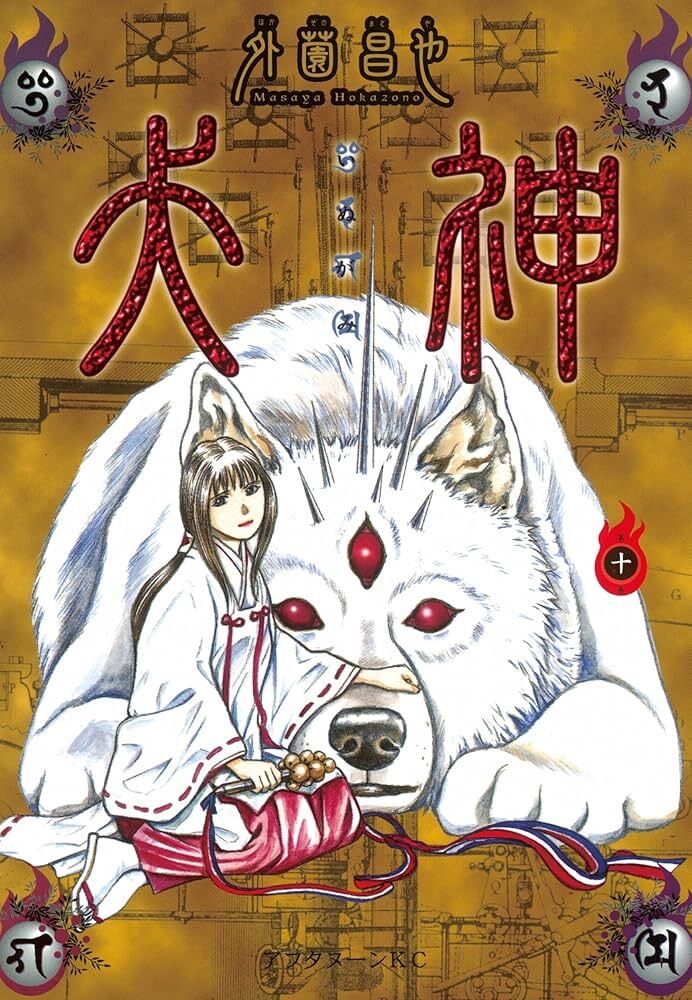

In Contemporary Culture

The title character, a half-demon of canine origin (hanyō), is not a literal inugami, but embodies many of its traits: loyalty, strength, an inheritance of violence, an internal split between the human world and the world of demons. His brother, Sesshōmaru, also carries the traces of this spiritual legacy—beauty, coldness, and wildness. Inuyasha is a reinterpretation of folklore through the lens of a story about identity, family, and betrayal.

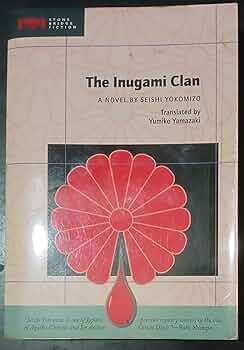

At the other end of the spectrum lies the detective novel Inugami-ke no ichizoku (The Inugami Clan) by Seishi Yokomizo—a classic of Japanese mystery literature. The story of a family cursed by inheritance, secrets, and murder is a transposition of folklore into the realm of social drama. Inugami here is no coincidence—it evokes associations with ancestral loyalty, wrath, and a spiritual legacy that cannot be shed.

Contemporary horror cinema also draws on this motif. In the 2001 film Inugami, we encounter a suffocating, almost Shakespearean tale of family secrets and a curse that tears a rural community apart from within. The dog spirit becomes a metaphor for rural Japan—beautiful but stifling, rooted in memory and violence that cannot be erased.

Final Reflections

In almost every culture, the dog is a symbol of loyalty. In Japan—especially so. The famous story of Hachikō, the dog who waited for years for his deceased master, has become a modern national myth. But inugami is Hachikō in a distorted mirror. It is the image of loyalty betrayed and exploited. The spirit of a dog who loved too deeply—and who cannot leave. In this sense, inugami is not merely a folkloric curiosity—it is a symbol of wounded emotion, of love that, through lack of reciprocity, transforms into a curse (it bears some resemblance to that specific feeling which the Japanese language describes as urami—more on that here: Urami: the Silenced Wrong, All-Encompassing Grief, Fury — What Emotions Are Encoded in the Character “怨”).

The practices of its “creation”—starvation, imprisonment, ritual death—speak of something even more terrifying: suffering can be a source of power. Hunger, pain, violence—strip away one’s humanity (if we extend the metaphor of inugami to human relationships), but they can give rise to blind hatred—easily weaponized, like a tool. The dog is taken from nature, removed from the animal world, and transformed into something profoundly human—though terrifying.

It is a present but hidden spirit. One that never disappears—unless it is acknowledged and named.

>> CZYTAJ DALEJ:

Inunaki Tunnel: Brutal Murder, the Howling Dog, Buried Workers, and Horrific Experiments...

Sugisawa – A Nighttime Massacre Erased a Village from Japan’s Map

The Shogun Introduces Animal Cruelty Laws in 17th-Century Edo Japan

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!