Psychological Landscapes of Trauma in Contemporary Ukiyo-e – The Hyperaesthetics of Pain in the Paintings of Natsuko Tanihara

Is suffering a decoration, or a desperation?

In contrast to the aesthetic coolness of Superflat or the irony of Murakami, Tanihara creates art that does not observe – it feels. Her baroque has no axis, only tension. Her contemporary ukiyo-e is not a memory – it is a wound. Through this hyperaesthetization of pain, she produces painting that cannot be passed by indifferently – for it strikes the senses and lingers beneath the eyelids. At times, the light in her works resembles a sky after catastrophe. At times, a theatrical spotlight over a domestic tragedy. But it always exposes rather than absolves. And Tanihara – though she never speaks plainly – makes one understand: the wounds you cover with glitter will still hurt.

Who is Natsuko Tanihara?

Her artistic path led her through Kyoto City University of Arts – initially through Nihonga, traditional Japanese painting using ink, pigment, and quiet contemplation. But where others saw spiritual balance, she felt dissonance. After half a year, she abandoned tradition and turned to Yōga – Western oil painting techniques. Yet the white, classical canvas gave her no peace – she said that “the brush did not want to move across it.” Only black, matte velvets began to absorb her visions. Influenced by the fact that American expressionist Julian Schnabel painted on velvet, Tanihara found her medium – a surface that absorbs light and reflects only what darkness allows us to see.

After returning from a year of study in Paris – where she visited museums and absorbed the directness of Northern Renaissance art, from Rembrandt and van Eyck to Grünewald – she came back to Japan to begin her doctorate. There, her career began to accelerate. Recognized at prestigious VOCA exhibitions of young art, awarded by cultural foundations (Gotoh Foundation), supported by the cities of Kyoto and Osaka (Sakuya Konohana Award), a resident in Torajirō Kojima’s studio under the auspices of the Ohara Museum in Kurashiki, and featured on the Break Zenya program – Tanihara was from the very start regarded as a remarkable artist.

And yet, it is difficult to speak of her as a “recognized” artist in the conventional sense. This is not a career, but a story of enduring pain, of a suppressed scream turned into color. In a Japanese culture where elegance is often mistaken for restraint, and suffering for honor – her paintings are brutally honest. Sometimes too honest. That is precisely why they are necessary, even if not to everyone’s taste.

Matter and Darkness – What Does Tanihara Express Herself Through?

In Natsuko Tanihara’s work, technique is not just craft – it is a philosophical structure. Her paintings are not born on white canvas, but on black velvet that reflects no light, only absorbs it. Velvet is no accident – it is a choice of tremendous power. In interviews, she said that classical white canvas paralyzed her brush; “it did not want to move across it.” Only velvet – soft, heavy, with a surface “as if alive” – allowed her to paint as she felt. Its matte surface absorbs light like night – and thus became the perfect foundation for paintings born from darkness, pain, and memory.

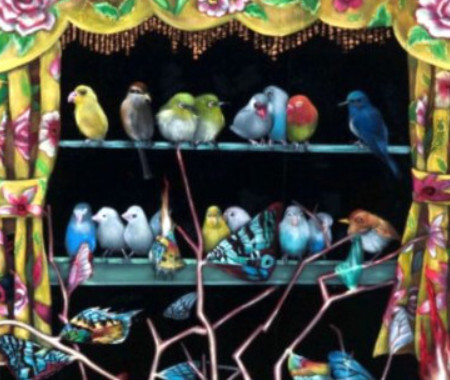

It is from this darkness that her figures and symbols emerge – glittering, sensual, and at times kitschy. Tanihara incorporates glitter, sequins, crystals, and mica into her paintings – materials more familiar in the fashion industry than in academic painting. But their presence is no empty ornament. On the contrary: a sequin on a girl’s body, glitter in a mermaid’s eye, shimmering scales scorched in a Japanese irori hearth – all confront the viewer with violence dressed in a decorative costume. Tanihara’s ornamentation is therefore not an escape from content, but its very essence – one might even say, its escalation. In this vividness bordering on the gaudy lies a brutal truth about the world: that suffering can be coated in glitter – and often is.

The sources of this aesthetic lie deep in her biography. As a child, she spent long weeks in her grandparents’ rural house in Aomori Prefecture, where she was introduced to the world of old kimono and ornamentation – both Japanese and that which, over centuries, filtered into Japan from China and Europe. She was fascinated by the golden threads of obi, the floral patterns on silk, and at the same time the spiritual dread of the old countryside house where lights went out at seven in the evening. That childhood perception of the world – sensual, yet tinged with unease – still resonates in her work today.

Tanihara’s painting balances between hyperrealism and symbolism. Her figures – girls, mermaids, oiran (who is an oiran? – Oiran - The Highest Courtesan and Master of Art with the Entertaining Escort of Geisha: A Story Misunderstood in the West) – illuminated by the glow of unreal light, are rendered with almost photographic precision. Yet these are not portraits or scenes from life. They are images on the border of waking and dreaming, in which everything – from body posture to the arrangement of flowers – is significant. Her world is a theatre, where everything is the scenography of suffering, even when it sparkles. Through this hyperaestheticization of pain, Tanihara produces painting that demands to be felt – for it strikes the senses and lingers beneath the eyelids.

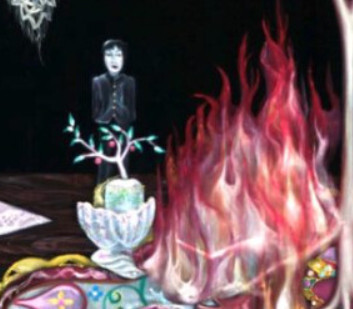

The light in these paintings is not a natural source – it is light borrowed from the art of Caravaggio: dramatic, spotlit, high in contrast. Chiaroscuro – light and shadow – not only constructs space but creates emotion. Sometimes light is illusion, as in This Impure World (2015), where the red glow on the horizon evokes a post-catastrophe sky. Sometimes – as in Child Room – it is artificial, theatrical, illuminating a scene of domestic drama. But it always exposes: it reveals, but does not absolve.

Tanihara, painting with “black” light on a black background, is perhaps the darkest of all living Japanese artists. But her darkness is not nihilism – it is an act of courage. Because it is precisely thanks to this darkness, which does not try to be beautiful, that her paintings begin to shine. Let us now take a closer look at some of her works to better understand her message.

“Child Room”

– Natsuko Tanihara, 2014

What immediately draws attention is the velvet background of the painting – a deep black that does not reflect light, but absorbs it. The fabric is not merely a carrier of the image – it is an active participant in the composition. Its absorbency emphasizes the loneliness and isolation of the scene. The girl seems almost suspended in emptiness – a body without a place, a memory without a future. The contrast between her white garment and the surrounding darkness is not only formal – it is also a narrative about delicacy exposed to brutality. The light, which in classical painting served to depict divinity or revelation, here takes on an oppressive character – it illuminates vulnerability. The entire scene is enclosed in a nearly theatrical structure: symmetry, curtains, decorations, and the stillness of the figures make us spectators of a drama we cannot interrupt.

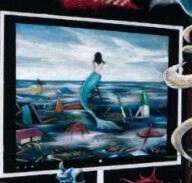

This Impure World

– Natsuko Tanihara, 2015, Japan (Kyoto or Kansai)

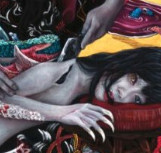

According to Nakai’s interpretation (curator at the National Museum of Art in Osaka), the painting aligns with the visual order of the Baroque – we have an “open form” (gestures that don’t fit into symmetry), “recession” (spatial depth), a painterly style of blurring (softened contours of kimono and tatami), and a multitude of elements integrated into a single whole. The monitor showing the tsunami introduces a historical and social aspect – clearly referencing the earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, connecting a personal, intimate narrative with collective memory. This element becomes a “window” between the depicted world and the real trauma of Japan.

Psychologically, the painting captures a fusion of beauty and destruction: the oiran and her companions seem to be participating in a ritual – perhaps aesthetic, perhaps spiritual – while the world behind the screen is falling apart. The tatami cracks and lifts, but the figures maintain their balance, as if ignoring the catastrophe – a moment suspended between ignorance and awareness. Tanihara asks: how much silence can we endure when the world behind us is crumbling, and we remain formal and powdered?

Philosophically, this work is a metaphor for our ukiyo – the floating world, in which beauty and decadence are compressed into the mask of culture. It is a flat theatre, where decorations matter more than truth, and glitz is a mask instead of genuine pain. The painting cannot console – it offers no relief, but urges the question: does beauty always obscure deeply rooted wounds? Is the essence of humanity ritual, ignorance, or perhaps the courage to look into the unknown?

“Atonement”

- Natsuko Tanihara, 2019, Kyoto, MEM Gallery

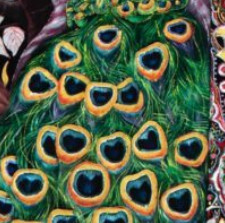

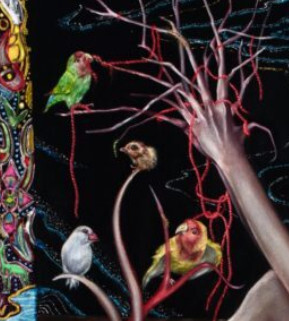

In a twilight thick as velvet, amidst lush, untamed vegetation, a naked woman remains motionless. Her body – veiled in a translucent, pearlescent fabric – appears naturally fused with the nature around her. The woman sits freely, one knee bent, her face lifted straight ahead. Her eyes gaze slightly downward, lips curved in contemplation – as though she were searching not outward but inward for answers. Above her – delicate birds on a slender branch, cherry blossoms, to the right – peacock feathers in deep, hypnotic shades of green and gold. Every leaf, every tuft of grass is meticulously rendered, almost hyperrealistic, in contrast to the blackness that is not just a background, but complete void. The painting falls into heavy silence, and in that tense stillness, it almost trembles.

The title – Atonement – guides us toward moral and existential reflection. It is not confession or public remorse – it is an intimate, silent meditation. The woman does not beg for forgiveness – rather, she accepts its absence. Atonement here is not a religious ritual but a state of being: an awareness of wrongs that will not be forgotten, but which – perhaps – she may come to terms with, observing them dispassionately and naming them. As if the act of naming were the first step toward understanding. Toward reconciliation.

In this context, the peacock feathers are ambiguous – they symbolize both vanity and suffering, beauty and the burden of expectation. The woman’s body seems to suggest eroticism, but it does not radiate it; she appears absent – as if she no longer exists in the present, but in a space suspended between memory and purification. The birds are silent. The vegetation offers no life. Nature does not save – but it reminds us that everything that lives must pass through its own shadow.

The left hand, over which the woman leans, unfolds unnaturally – the fingers elongate, fork, resembling twigs. Is this a process in which nature consumes the woman? What strikes here is the moment of self-contemplation – the woman’s gaze is not full of fear, but calm and seeking understanding. It is the moment when a person realizes that their body – that which is personal – is already part of a world that surpasses them. These branches are therefore not only an organic transformation, but a symbolic sign of irreversibility – of guilt, trauma, pain that have grown into identity like trees into the earth.

And finally – the thread. Red, like from a torn sweater, it stretches thinly from below to the hand, to intertwine with the branching fingers. What is it? Is it the thread of fate? Or of guilt? A thread of memory? In both Eastern and Western mythologies, the red thread often binds people with destiny, love, death. Here it seems to bind the body to the past – not letting go. It leads nowhere – only deeper into oneself. It is a physical form of spiritual entanglement: the woman is both victim and spinner, the one who weaves and the one entangled.

Everything in this painting – the branches, the hand, the yarn – speaks with a single voice: of the fact that a person cannot escape themselves, but perhaps – by looking without fear – can understand that even suffering can have structure. That every wound has its own pattern. That atonement is not the erasure of guilt – but the realization that we are still alive, whether or not we deem ourselves worthy of that life.

What, then, is the “little goat”?

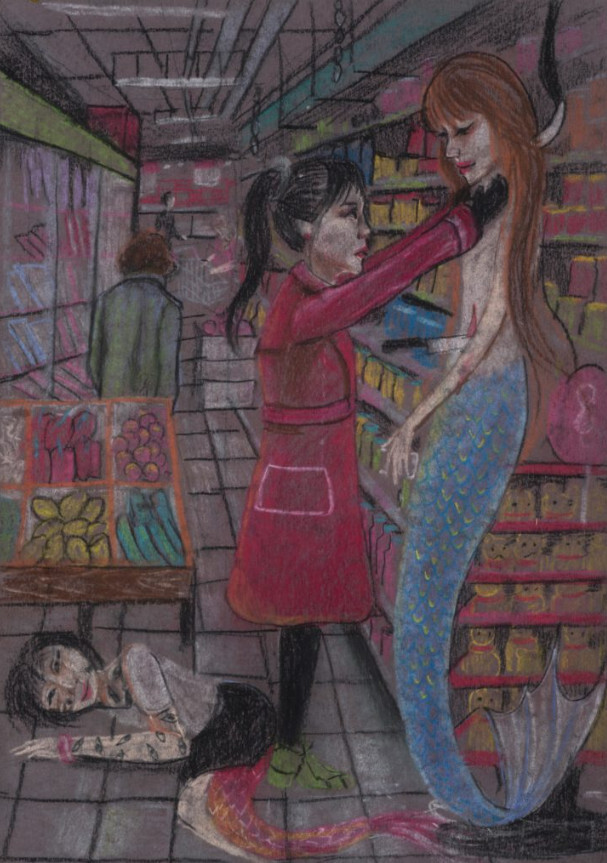

“SADO”

- Natsuko Tanihara, 2015

At the center of the painting SADO, we see a girl in a black-and-red kimono with an intricate pattern, seated before a golden byōbu screen, whose rich, undulating landscape composition evokes the classical painting of the Rinpa school. On her lap rests a naked, half-living mermaid – her long, white body with red scale accents stretches across nearly the entire painting. The girl, emotionless, almost ritually, cuts into the mermaid’s body, gazing impassively downward, as if she herself is unsure whether she is enacting revenge or performing a sacrifice.

Tanihara applies here her characteristic technique: velvet as background that reflects no light, imparting not only the aesthetic of night but also a sense of spiritual void. On this ground shimmer layers of oil paint, pastels, glitter, sequins, metallic flakes, and resin, creating an effect of flickering, almost hypnotic texture. The composition draws on the classical structure of Japanese scenes (the screen as a world-frame) but is interrupted by a brutal gesture – the act of cutting, which severs not only the mermaid but also the painterly harmony. The color palette blends gold, black, white, and red – colors of ritual, violence, and sacrality. Equally important is the disharmony of scale and perspective: the mermaid’s body elongated and unnatural, the objects too numerous and too vivid – as though the depicted world were a dream or hallucination.

The golden screen in the background – a classical symbol of Japanese beauty, harmony, and prestige – contrasts with the brutality of the cutting act. As if Tanihara were saying: beneath the surface of tradition and gold there is always a wound. The mermaid’s body, white and scaled like porcelain, is profaned – this is an act that breaks the silence, violates the taboo, but also provokes the question: who has the right to transformation, and who is forced into sacrifice?

All the objects in the foreground – food, incense, embroidery, ornaments – echo traditional Japanese rituals, but also their caricature. They resemble offerings placed on a household altar – only here, it is unclear who is the deity, and who is the dead. What was meant to be beautiful becomes heavy, too intense, too glittering – as if the decoration had begun to suffocate life.

SADO is one of Tanihara’s strongest and most unsettling works – a painting that, on the formal level, captivates, but on the symbolic level – disturbs and provokes. It is not only a tale of violence and transformation, but also a reflection that beauty – if left unquestioned – can become a form of cruelty. The mermaid is not a mythological creature – she is femininity itself: other, alien, cut open before our eyes. And the girl with the knife? She is each of us – the one who watches, perhaps scorns, but cannot look away.

The Shadow of Ukiyo-e, the Spirit of the Baroque

The work of Natsuko Tanihara is not merely painting – it is a kind of ritual, a dark spectacle performed after catastrophe. Her canvases – though often shimmering with glitter, sequins, and light – grow out of the deep melancholy of Japanese ukiyo-e tradition. But not the cheerful one, known from themes of girls in kimono and blooming cherry blossoms, rather the original, painful one – hidden at the roots of the very word ukiyo (浮世 / 憂き世), meaning “the world of sorrow” or “fleeting suffering.” In this context, critic Nakai Yasuyuki rightly calls her “the contemporary heir to Iwasa Matabei,” whose dramatic illustrations, such as The Tale of Yamanaka Tokiwa, are full of crime, suicide, and ghosts. In Tanihara’s art – as in Matabei’s – violence and death are not sensationalism, but a starting point for deeper reflection on the fragile condition of existence.

Thus, her art stands in direct contrast to the Superflat movement, represented by Takashi Murakami. Where Murakami offers flatness, irony, and an intellectual play with the signs of pop culture, Tanihara reigns with depth – both literal and metaphorical. Instead of cold detachment, we find feverish expression; instead of strategy – sincerity. Tanihara does not deconstruct the image but enters its entrails. She does not quote the world – she experiences it. Her aesthetic is sharper and more risky – not an aesthetic puzzle, but a scream bound in velvets and gold leaf.

Painting as Exorcism

Natsuko Tanihara is an artist whose voice rises from silence – the kind imposed by social conventions, the one born of childhood trauma, and the one that falls after disaster. Her paintings are not a response to the world but a rupture in its surface: a trace of a generation growing up in Japan after Fukushima, in the era of digital numbness, where every gesture can be both decoration and desperation. In Tanihara’s aesthetic, deep sensitivity intertwines with a refusal of superficiality – it is a revolt against a culture that teaches us suffering must be silenced and wounds covered in glitter.

In this context, her art becomes something more than self-expression. It is a tool for salvaging memory, but also a ritual of severance – an act that does not explain or console, but allows survival. Each painting is a labyrinth, where the goal is not to find a way out, but to get lost – and in that disorientation, to recognize one's own emotions. Her works are like stifling dreams – painful, uncomfortable, but impossible to forget.

These are not paintings meant to please. They are paintings meant to hurt. Their beauty is poisoned, their form – too intense to be purely aesthetic. But it is precisely for that reason they stay under the skin, pulsing somewhere beneath the eyelids long after we’ve left the exhibition. Because Tanihara does not simply offer us a vision of the world. She offers us a confrontation with what, in that world, remains unspoken.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Obsession with Self-Destruction: How Yayoi Kusama's Art Delves into the Nightmare of Mental Illness

Faulty Man in a Box: The Mechanical Nightmare of Tetsuya Ishida's Paintings

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!