Blue Japan – how indigo 藍 (ai) dyed Edo and became the color of work, purity, and harmony

The color of the shogunate era

For the people of Edo, it was something natural, almost invisible, like the air. For foreigners arriving in the 19th century, it was a revelation. British chemist Robert William Atkinson, who visited Japan in 1874, wrote:

"This country is blue. The roofs, the clothes, the curtains — everything is blue."

The rigorous ken’yakurei sumptuary laws of the Tokugawa shogunate made 藍 (ai) the color of Edo. Bright colors and silks were reserved for the elite; peasants, craftsmen, and merchants wore simple, practical fabrics. Indigo was ideal: cheap, durable, antibacterial, and protective against both sun and insects. 藍 (ai) became the color of labor — the noragi work jackets of farmers, the yukata of townsfolk, the belts of fishermen — and of purity: noren curtains before sentō bathhouses, blue picnic sheets for hanami, tenugui hand towels, and rice sacks.

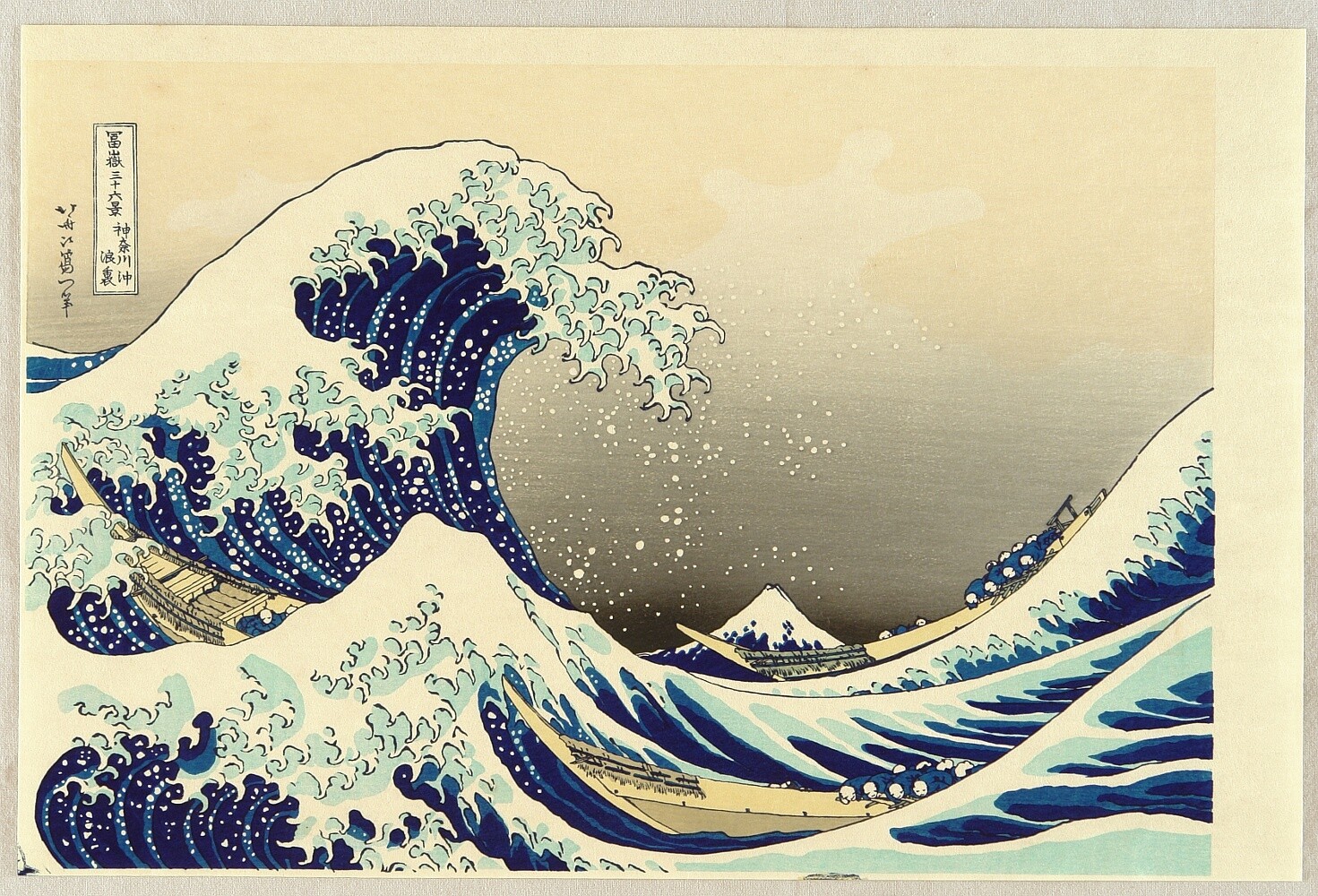

藍 (ai) permeated daily life, yet in Japanese aesthetics it symbolized purification, breath, and harmony between humans and nature. Today, when we look at Hokusai’s or Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e, we see not only landscapes of Edo but a pulsing blue — one of the purest symbols of Japanese aesthetics. Let us now look more closely at this color, its kanji, and how it helped shape the aesthetic of the Edo period.

The kanji 藍 and the meaning of blue: “ai”

「藍,染青草也。从艸,監聲」

(“藍: the grass used for dyeing blue; composed of the grass radical, with the phonetic 監.”)

This shows that the original meaning of the character encompassed both the dye plant and the practice of blue dyeing, rather than an abstract concept of “blue” itself.

From the continent, the character’s story travels to the archipelago. In classical China, 藍 (Lán in Chinese) referred to the plants used to produce dye (various species of indigo) and, by extension, to the blue color derived from them. In Japan, the character was adopted with the reading あい (ai), coming to name the plant itself (Polygonum tinctorium), the dye obtained from it, and the entire craft: 藍染(あいぞめ)— aizome, literally “dyeing with ai.” During the Edo period, dozens of technical and artisanal compounds arose around this practice.

The philosophy of ai is beautifully captured in a famous proverb from classical tradition (quoted here in its Japanese form, not Chinese):

青は藍より出でて藍より青し

— from the “Quanxue” (勸學) chapter of Xunzi (3rd century BCE):

"Blue comes from indigo, yet it is bluer than indigo itself."

Its meaning can be read in two ways. First, the master–disciple dynamic: through practice and discipline, the student can surpass the master — the very foundation of Edo’s artisanal pedagogy. Second, nature–culture: the raw plant is the beginning, but the culture of work (fermentation, vat rules, oxidation cycles) draws from nature an intensity that nature itself “does not reveal” without human intervention. This thought captures aizome perfectly: the leaf holds the promise of dye, yet only through living fermentation — nurtured by human hands — is the deep blue 藍 (ai) born.

From the perspective of language and writing, it is striking that the character unites 艹 (plant life) with a phonetic whose ancient imagery evokes a vessel and “looking into it”: plant + vat + eye/attentiveness — biology + craft + mindfulness. This triad of meanings resonates profoundly with the Japanese idea of learning through repetition, with the rhythm of the hands, and with the quiet ethics of work.

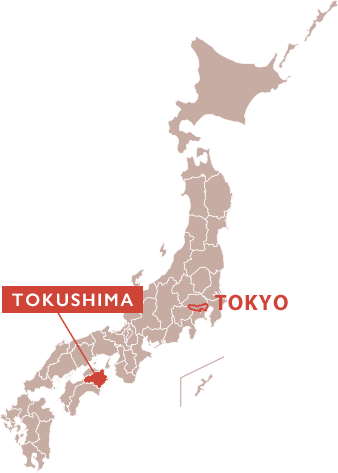

Tokushima and “Awa-ai” – the birthplace of Japanese indigo

Tokushima’s climate seems almost designed by nature specifically for this plant. In summer, the humid heat spurs rapid growth; in winter, the earth rests, and the crystal-clear waters of the Yoshino-gawa irrigate the fertile fields. This environment created perfect conditions for cultivating indigo plants — so perfect, in fact, that as early as the Kamakura period (12th–14th centuries), this region became the beating heart of Japanese textile dyeing. Over time, Tokushima developed its own style, its own craft, and its own legend.

Tokushima is also famed for its wealth of dyeing techniques, which, during the Edo period, allowed aizome masters to create an endless variety of patterns:

♦ Shiborizome (絞染め) — Japanese “tie-dye”; the fabric was tied, twisted, and bound to create asymmetrical, fantastical patterns of white and blue.

♦ Itajimeshibori (板締絞り) — a variation of shibori; the cloth was folded and clamped between wooden boards, resulting in geometric designs reminiscent of origami.

♦ Bassen (抜染) — after uniform dyeing in indigo, patterns were created by applying bleaching agents, producing intricate ornamental motifs.

♦ Roketsuzome (蝋結染め) — the most demanding technique, in which wax was carefully applied to the fabric before dyeing, creating delicate, hand-painted illustrations.

Each of these methods was, in the Edo period, not merely a craft but also an everyday aesthetic. In a world where luxury was restricted by ken’yakurei (倹約令) — sumptuary laws that forbade commoners from wearing silk or vivid, expensive dyes — indigo became the color of universal elegance. It was used to dye noragi — the work kimono of farmers, tenugui — thin cotton hand towels, and noren — shop curtains swaying gently in the streets of Edo.

Indigo in everyday Edo — the color of work and purity

The Edo period was a world governed by ken’yakurei (倹約令) — sumptuary laws regulating the appearance of residents according to their social class. The Tokugawa authorities sought to maintain strict hierarchy and forbade the lower classes from wearing luxurious fabrics or vivid, costly dyes. Purples, scarlets, gold, and even certain shades of green — all these were reserved for the aristocracy and high-ranking samurai. Peasants, merchants, craftsmen, and fishermen were expected to dress modestly, in subdued, natural, “pure” tones.

And it was precisely here that indigo — 藍 (ai) — became salvation.

Edo in shades of 藍 (ai)

Blue was literally everywhere. One only has to look at ukiyo-e from the period — Hiroshige, Hokusai, Kunisada, Yoshitoshi — to see scenes of Edo life steeped in blue. For Europeans visiting Japan in the 19th century, this was a shock. Robert William Atkinson, the British chemist who arrived in Japan in 1874, is said to have remarked:

"This country is blue. The roofs, the kimono, the curtains — everything is blue."

It was at this moment that Japanese indigo gained its now-famous name: “Japan Blue.”

The color of work

In the Edo period, indigo was first and foremost the color of work. Anyone who rose at dawn and returned late in the evening, exhausted, wore the color 藍 (ai).

Peasants put on simple noragi (野良着) — loose, short kimono made of patched cotton. They wore them for years, and when the fabric began to fray, it was reinforced with additional layers — thus were born the famous boro (襤褸), patchwork garments that today are icons of wabi-sabi aesthetics.

Hikyaku couriers (飛脚), sprinting through Edo’s streets with parcels, wore light jackets in the color 藍 (ai), adorned with white emblems of their guilds (more about couriers in Edo here: The Shogunate’s Reliable Couriers – Hikyaku and the Carrier Market of Medieval Japan). Even construction workers used indigo-dyed materials, because their resistance to sweat, sun, and bacteria was invaluable.

Samurai and indigo 藍 (ai)

Although 藍 (ai) became the color of peasants and craftsmen, samurai wore it as well — albeit differently. Beneath their richly decorated yoroi armor were layers of shitagi (下着) — undergarments, shirts, and hakama, often dyed with 藍 (ai). This was not a matter of fashion but of practicality: indigo had antibacterial effects, protected small wounds from infection, repelled insects, and kept the fabric fresh.

Among samurai, the shade 勝色 (kachi-iro) — “the color of victory” — was particularly prized: a deep, almost black blue obtained by repeatedly immersing the fabric in the 藍 vat. It was worn in battle as a talisman of good fortune.

Aesthetics and emotion — “Japan blue” in art

There is something deeply moving in the way indigo blue — the color of work, purity, and everyday life — also became the color of longing. In the Edo period, 藍 (ai) infiltrated not only the lives of city dwellers but also art, aesthetics, and feeling, becoming one of the most important symbols of Japan’s visual identity. Thanks to it, Edo is remembered not only as a metropolis of trade and craft, but also as a land of blue landscapes, blue curtains, and a quietude hidden in the contrasts of white and indigo.

Ukiyo-e and the blue revolution

As a result, ukiyo-e — woodblock prints that had until then employed a rather subdued palette — suddenly blossomed with new shades of sky and sea. Hokusai used bero-ai in his famous series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji.” The deep waves of “The Great Wave off Kanagawa” would not be so dramatic were it not for the contrast between the almost navy blue of the sea and the snowy white of the foam. The same holds for his “Red Fuji” and views of rivers — thanks to the new pigment, the water became lively, dynamic, almost three-dimensional.

Sometsuke — Edo’s blue ceramics

Sometsuke was not reserved for the elite — this porcelain appeared in townspeople’s homes, on merchants’ tables, in teahouses and inns. It was an everyday blue, yet far from banal: calming, bringing harmony to interiors and ceremonies.

“Japan blue” through foreign eyes

For the inhabitants of Edo, 藍 (ai) was self-evident, but for foreigners arriving in Japan in the 19th century, it was a true revelation. Robert William Atkinson, the British chemist who in 1874 studied Japanese dyes, popularized the term “Japan blue,” which quickly entered the European lexicon.

The greatest strength of 藍 (ai) aesthetics, according to Hearn, reveals itself in simple juxtapositions of blue and white. In the Edo period, this duo dominated not only clothing and ceramics but also decorative textiles, curtains, bedding, towels, and even toys. Yet it was not a purely decorative choice — blue and white brought a sense of freshness, order, and cleanliness.

Yukata in blue-and-white waves, noren adorned with stylized kanji, the geometric kasuri patterns on kimono, porcelain with motifs of pine and crane — all this created a coherent aesthetic language that united practicality with the poetry of everyday life.

We find the same aesthetic language in ukiyo-e: there, blue meets the white of snow, the white of sea foam, the white of plums and cherries. Japan in the Edo period was a world in which a simple, natural palette of colors allowed artists to tell stories filled with deep emotion.

Metaphysics or pragmatics?

And yet blue did not remain solely in the past. Today it lives on — though in different forms. You can see it in the suits of salarymen, in school uniforms, in the materials of minimalist Midori and Traveler’s Company notebooks. It is the same color once worn by peasants, craftsmen, and merchants — the color of work, simplicity, and everyday dignity — and at the same time a color that has become synonymous with modern Japanese design, harmony, and discipline.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Machiya: What Were the Townhouses of Edo Like? – The Lives of Ordinary People During the Shogunate

Let’s Go Shopping in Japan… During the Tokugawa Shogunate Era in Edo

The Color Essence of Japanese Aesthetics: Vermilion Red, Immaculate White, Deep Black

How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!