The Ukiyo-e Business: How Hanmoto Balanced Between Shogunate Censorship and the Art Market Trends in Edo

The Business of Four Masters

They were masters of marketing as well. In Edo’s bookstores, teasers for upcoming series were displayed — carefully crafted announcements designed to stir the imagination and build tension. For the most awaited releases, people queued in front of shops, and a feverish collector’s craze could sweep through the city — from humble street vendors and craftsmen to samurai households.

Balancing between market and law was an everyday struggle. Censors stamped their seals — kiwame (極め, “approved”) and aratame (改め, “inspected”) — yet hanmoto evaded restrictions with finesse, smuggling in subtle allusions and, at times, even veiled criticism of the shogunate itself. Tsutaya Jūzaburō II, one of Edo’s most famous publishers, once commissioned Hokusai to illustrate a collection titled Kyōka to Kanshi (“Playful Songs and Chinese Poetry”). The delicate portraits of women turned out to be too provocative, and his chief bookseller was arrested and publicly flogged. In the world of ukiyo-e, beauty carried its price, and the line between success and ruin was as thin as the mulberry fibers of washi paper.

Today, we step behind the scenes of the ukiyo-e workshops to uncover how these masterpieces were truly born — how four masters, the artist, carver, printer, and publisher, united their skills in a precise, almost ritualistic choreography of creation. We reveal how hanmoto could sense the city’s pulse, dictate trends, and ignite desires while constantly dancing on the edge of law, censorship, and scandal. It was thanks to their courage and calculated risk that we now have works fetching staggering prices at auctions — from hundreds of thousands of dollars for Hiroshige’s landscapes to over three million for Hokusai’s Great Wave.

“The Scent of Wet Wood and Pigments”

The boy, crouched quietly by the wall, clutched a waxed tablet in his hands. He noted down everything: the planned number of prints, the number of blocks, the estimated price per sheet, the name of the bookseller who would receive the first copies. He knew a single mistake could cost the master several ryō, and for the boy — perhaps his own hide.

Outside, Edo was slowly waking. From the clock tower near Nihonbashi came five tolls of the great bell — signaling the start of the tora no koku, the “hour of the tiger,” when merchants and craftsmen began their morning bustle (to learn more about Edo-period timekeeping, see here: The Hour of the Rat, the Koku of the Tiger – How Was Time Measured in Shogunate-Era Japan?). Soon, hay carts would rattle down the streets, and fishmongers would shout to lure their first customers. But inside the workshop, time flowed differently. The scent of wet wood, glue, and pigments filled the air, and each movement of the chisel, each sweep of the baren, each whispered word behind the curtain merged into a rhythm larger than any single person. A rhythm that created not just images, but an entire city captured in impressions.

It was then, for the first time, that the boy understood: ukiyo-e was never just an image on paper. It was an entire network of people, money, risks, dreams, visions, and emotions — all sealed within the lingering scent of wet wood.

The Mechanics of Ukiyo-e Creation

The making of ukiyo-e was never the work of a single artist — it was a precisely synchronized effort of four distinct roles, moving together like a finely oiled mechanism.

Eshi (絵師) — The Artist Who Began the Story

And yet, in Edo, the artist was far from the master of his own creation. It was the hanmoto — the publisher — who determined the format, number of colors, edition size, subject, and at times even the very title of the series. The eshi, though respected, was part of a larger machine — one driven not solely by artistic vision, but by the logic of the market and the desires of Edo’s townspeople.

Horishi (彫師) — Master of the Chisel and Patience

Work on the omohan, the key contour block, could take weeks, sometimes months, if the design demanded extraordinary precision. After finishing the main block, the horishi created additional color blocks, called irohan (色版), each dedicated to a single pigment. For richer designs, there could be a dozen of these, sometimes more than twenty.

Despite their immense skill, horishi usually remained anonymous, though it was their hand that determined whether the artist’s lines would survive on wood with all their intended subtlety. A single slip could ruin a precious cherry block — and with it, weeks of painstaking labor.

Surishi (摺師) — Master of Color and Light

The surishi brushed pigments onto the carved blocks using special tools, then carefully placed the washi sheet atop the inked surface, aligning it precisely with the kento (見当), the carved registration marks. He then reached for the baren (馬楝) — a tightly wound disc of bamboo fibers wrapped in leaves — and rubbed the back of the paper, pressing it firmly into the block. His movements were rhythmic and deliberate: too much pressure would damage the pigments, too little would produce pale, lifeless impressions.

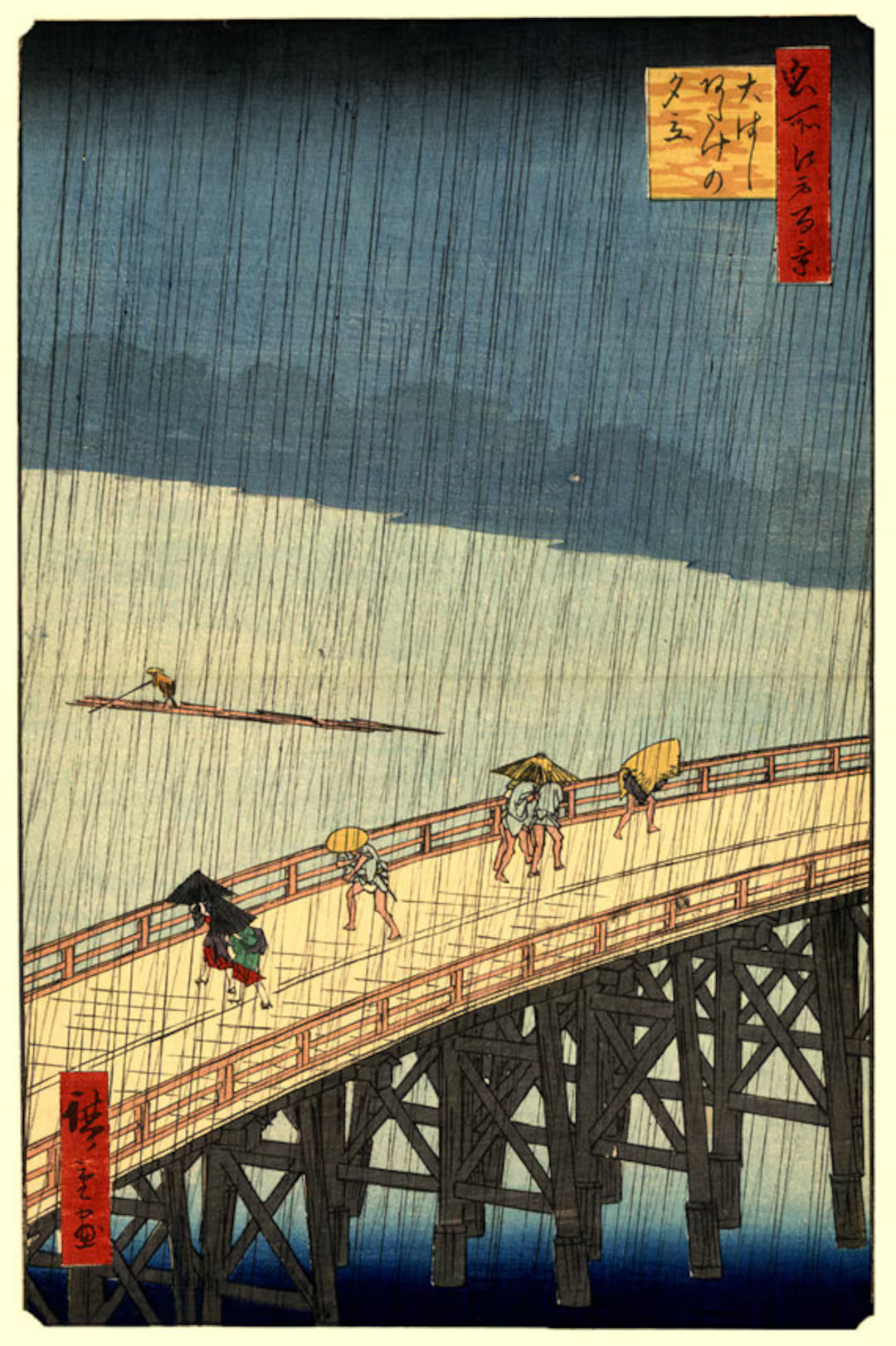

The surishi’s highest art was the technique of bokashi (暈し) — hand-shading the pigments directly on the block. Thanks to bokashi, Hiroshige’s sunsets seem to tremble at the edge of light and darkness, and Hokusai’s waves roll from the pure white of foam into the fathomless depth of Prussian blue.

Hanmoto (版元) — The Director in the Shadows

The hanmoto followed the pulse of the market and knew what would sell: sometimes portraits of kabuki actors, at other times courtesans of Yoshiwara, and, increasingly, landscapes — especially after Edo’s obsession with travel along the Tōkaidō road and pilgrimages to Mount Fuji took hold. It was he who commissioned the great series that defined ukiyo-e itself: Hiroshige’s One Hundred Famous Views of Edo and Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.

Materials — The Foundation of Beauty

Creating ukiyo-e demanded the highest quality materials:

- Cherrywood (sakura) — the most expensive, prized for its durability and ability to hold the finest details.

- Washi paper — handmade, thin, and light, yet resilient enough to endure repeated rubbings with the baren without tearing.

- Pigments — from natural colors like cinnabar, indigo, saffron, and sumi ink, to imported dyes that revolutionized the aesthetics of ukiyo-e. The most famous was Prussian blue (bero-ai ベロ藍), brought from Holland through Nagasaki in the 1820s (a curious fact: in Europe, it was once called “Hiroshige blue”). Thanks to it, Hokusai’s waves and Hiroshige’s blue-toned landscapes acquired a depth of color previously unknown in Japan.

The creation of ukiyo-e was thus a collective effort where artistry, technique, financial risk, and market awareness intertwined. Edo’s workshops pulsed like living organisms — filled with the scent of wet wood, the rhythm of chisels, the rustle of washi, and the hushed negotiations behind sliding screens. Each print was the product of four masters, each with different skills, responsibilities, and visions — yet together they gave birth to Japan’s first form of mass visual culture.

The Hanmoto — The Heart and Mind of the Business

In Edo, ukiyo-e was never just about talent — it was a matter of profit and loss (as, indeed, it often still is today) — and the hanmoto served as both its accountant and its director.

It was the publishers who introduced into ukiyo-e the very logic of events, turning each new series into a sensation. Buying a print became something greater than ownership — it was participation in a collective moment, the feeling of being part of Edo’s living, breathing culture.

The most gifted among them could sense moods and trends better than the artists themselves. Tsutaya Jūzaburō, a brilliant entrepreneur and visionary, kept his bookstores right on the edge of Yoshiwara, the pleasure quarter where wealthy patrons were always hungry for images of courtesans and kabuki actors. He discovered and promoted masters such as Utamaro and Sharaku, and he also supported the young Hokusai. His name did not appear on the woodblock prints, yet it was thanks to his strategies that illustrations sold by the thousands. A few decades later, Nishimura Yohachi III risked something entirely new. In an era when the market was flooded with images of beautiful women and theatrical scenes, he commissioned Hokusai to create a landscape series — “Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.” It was a bold experiment, but Yohachi recognized the growing popularity of Fuji-kō pilgrimages and won his bet with the market. The series proved triumphant and led ukiyo-e down a new path. Showing similar intuition, Uoya Eikichi, together with Hiroshige, created the monumental “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo” — a visual guide to the shogunate’s capital that fused tourism with fashion and urban pride.

The hanmoto understood that the market was capricious and knew how to play to its moods. When Edo succumbed to a fascination with kabuki theater, portraits of actors appeared in the stalls. When the city fell into a frenzy for Yoshiwara, subtly erotic portraits of courtesans were sold to its residents. And when censorship struck at shunga (erotic) prints, the hanmoto walked the edge of the law, selling them on the sly to the very same clients who publicly condemned such images (sound familiar). In the 19th century, as Japan discovered the beauty of travel, publishers turned to landscape. Hiroshige and Hokusai then created masterpieces, but very often these were the result of precise guidelines from the publisher, not solely the artist’s vision.

We know the artists’ names by heart today, but behind each of their successes stood someone else — a person who held neither chisel nor brush, but who planned, calculated, and risked his own fortune. The hanmoto was the heart and mind of the ukiyo-e business. He created fashions, steered the market, and decided what would become iconic and what would sink into oblivion. Artists might have been masters of their craft, but without the publisher their works would never have reached the hands of thousands of townspeople who fell in love with the images of the “floating world.”

The Economics of Woodblock Printing

The Economics of Woodblock Printing

Behind every ukiyo-e impression lay a world of money, calculation, and risk — a world we rarely consider when admiring the works of Hiroshige or Hokusai. In Edo’s workshops, art and commerce were woven together so tightly that neither could exist without the other. The making of woodblock prints was not the romantic act of a solitary artist, but a complex financial operation in which any mistake could mean the loss of one’s fortune.

Pigments were no less costly. For a long time, natural dyes were used. Everything changed in the 1820s, when Prussian blue imported from Holland reached Japan through Nagasaki. This intense, deep hue became an aesthetic revolution — it gave Hokusai’s waves an unprecedented depth and infused Hiroshige’s landscapes with that extraordinary, softly blurred melancholy of backgrounds achieved through bokashi shading. Prussian blue, however, was expensive and difficult to obtain. Publishers invested in it with wealthier clients in mind, counting on the color’s uniqueness to boost sales.

Although the technology was costly, ukiyo-e was produced for a mass audience. We sometimes call ukiyo-e the “pop art of the Edo era” — it was affordable, though never shoddy. A simple impression might cost the equivalent of a decent meal at a city tavern, while richer, full-color series could be priced many times higher. This made ukiyo-e accessible to townspeople, craftsmen, and even lower-ranking officials, while still preserving prestige and the status of collectible objects.

The economics of ukiyo-e were thus full of tensions and paradoxes. The prints were made for a broad public, yet their production required enormous investment. They were at once accessible and luxurious, mass-produced and collectible. In Edo, the image was not only art — it was a commodity, a vehicle of fashion, a marketing tool, and a medium of information. Ukiyo-e was born at the junction where aesthetics met commerce, where beauty emerged from the cold calculus and hot rivalry of publishers.

Censorship and Seals

Ukiyo-e was the art of the “floating world,” but its creators understood one thing perfectly: the strongest spark for the imagination often comes from what one is officially forbidden to see.

The Ukiyo-e Business Today

On the other hand, ukiyo-e has entered the global collectors’ market, where values have reached astronomical heights. Original impressions of Hokusai’s Great Wave off Kanagawa can fetch over three million dollars at Sotheby’s or Christie’s, while Hiroshige’s famous Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake has sold for hundreds of thousands. It is a paradox: prints that once cost no more than a hearty tavern meal in Edo are now treated as priceless treasures of world culture. The art market has transformed ukiyo-e into an icon of Japan — a visual code, a symbol connecting the nation’s past and present.

Seen in this light, it becomes clear that the spirit of ukiyo-e — the art of the “floating world” — has never vanished. It still lives in the hands of modern craftsmen, in museum halls and auction catalogs, but also in spaces the masters of Edo could never have imagined: the pop culture of the 21st century. Where Edo meets Tokyo, where old pigments blend with digital light, ukiyo-e finds its new life.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Utagawa – A School of Japanese Ukiyo-e Woodblock Prints Whose Masters Are Still Admired Today

"Foxfires" in Old Edo – A Nocturnal Gathering of Kitsune in Hiroshige’s Ukiyo-e

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Economics of Woodblock Printing

The Economics of Woodblock Printing