The Shogunate’s Reliable Couriers – Hikyaku and the Carrier Market of Medieval Japan

Precise, swift, reliable

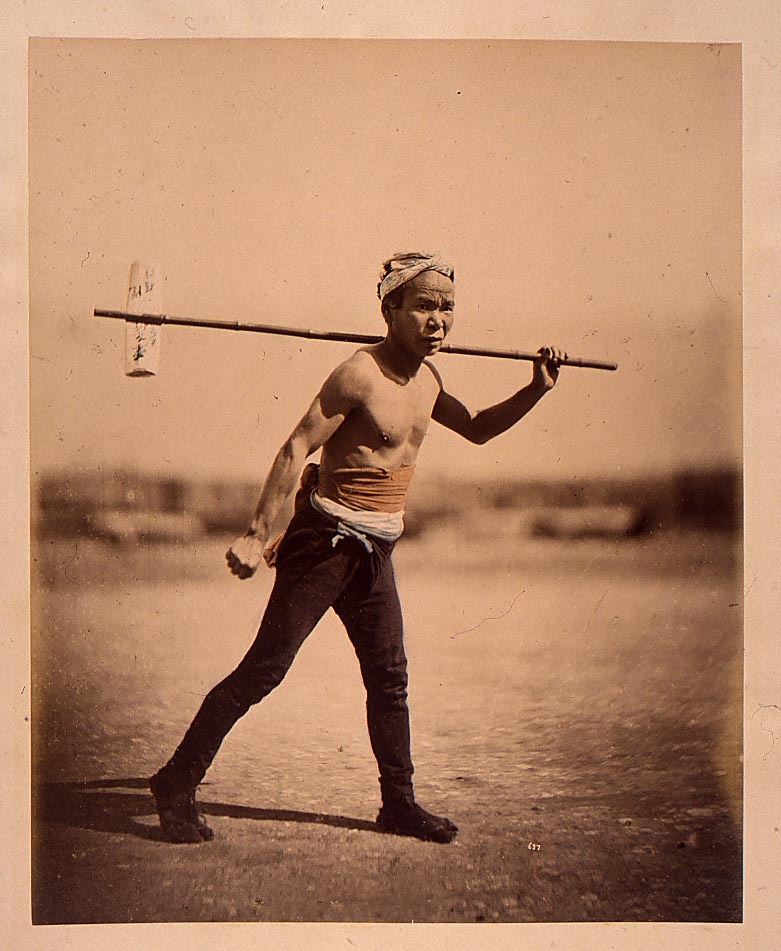

A Sprint Through the City

In one of the homes at the intersection of Honmachi and Nihonbashi streets, behind a paper shōji, a rustle was heard. An elderly woman, her face furrowed with age, slid the door open and looked toward the running figure. Her eyes, briefly illuminated by the oil lamp, recognized the rhythm and the sound. “It’s from Kenzō… He’s probably writing from Kyoto…” she whispered. In Edo-period Japan, mothers and fathers awaited the hikyaku like heralds of fate — their arrival was the voice of another, distant world. Often the world of loved ones — sons and daughters who lived in far-off prefectures.

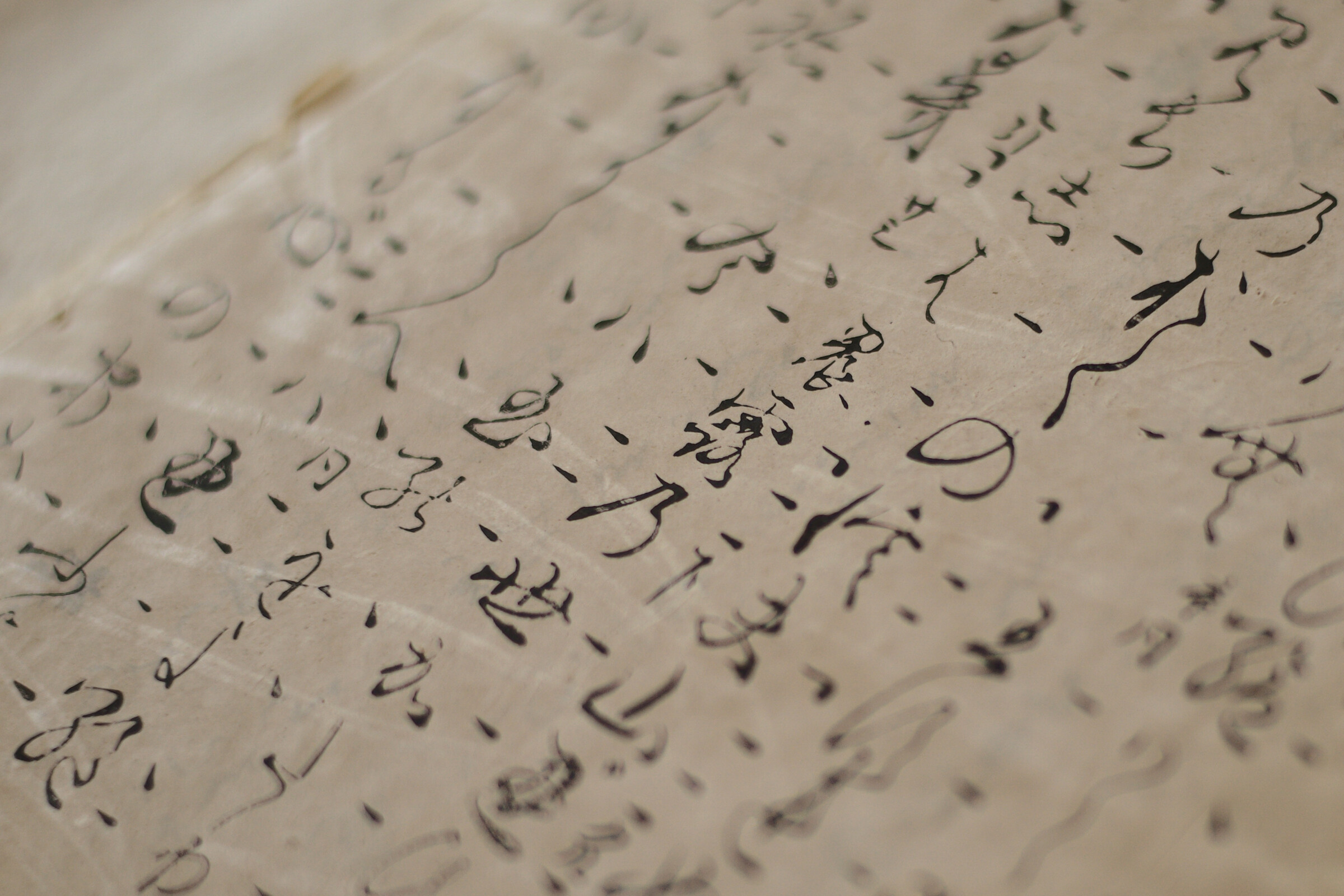

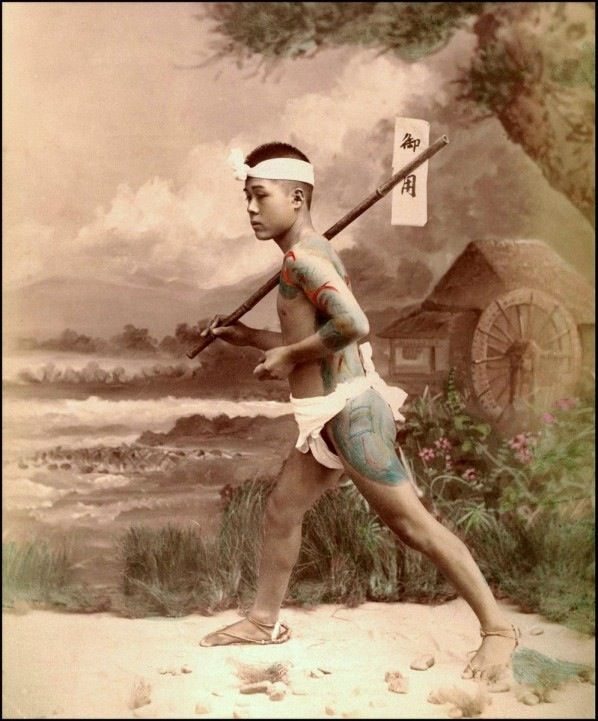

At midday, he stopped at a hikyaku-yado, a small inn designed specifically for messengers. He quickly ate a bowl of miso soup and a rice ball with salted plum, still not removing the box from his shoulder. In his travel register — hikyaku-chō — a new entry appeared, and shortly afterward, the courier set off again, leaving behind the scent of sweat, ink, and damp paper.

A standard journey between Edo and Osaka took six days. For those who paid more, faster options were available: haya-hikyaku completed the same route in four, or even three and a half days, running through the night, skipping some stops, and risking their own health. The fastest couriers could deliver a message in under 48 hours — though the price for such a feat reached several ryō and was affordable only to the wealthiest.

Rain began to fall as the courier reached the Ryōgoku-bashi bridge. Streams of water ran down his back, the wet box gleamed with a dark sheen, like black lacquer covered in pearly rain. Somewhere inside it lay a letter — perhaps an official document, perhaps a love confession, perhaps a farewell. To the courier, it made no difference. But to the one waiting on the other side of the bridge, it was a priceless gift. And it was precisely this bond, this invisible connection between people, cities, and hearts, that the hikyaku bore upon their shoulders.

Who Were the Hikyaku – 飛脚?

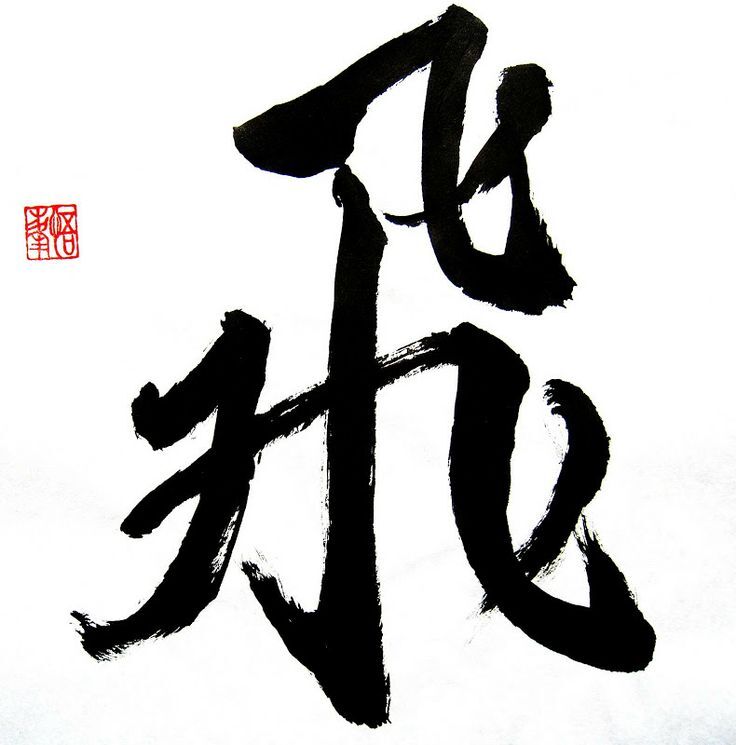

The first character, 飛 (hi), means “to fly” or “to soar.” At its core lies the image of a bird in flight — the original, classical form depicted outstretched wings in the air, with additional markings suggesting upward movement. The character carries strong connotations of lightness, freedom, and speed — in classical literature, it was often associated with the instantaneous shift of place, with unbounded movement that defies gravity.

The second character, 脚 (kyaku or ashi), means “leg,” or more precisely: “a leg in motion.” This character is used not only in anatomical contexts but also as a unit of measurement (e.g., in the expression isshaku — approximately 30 cm), or as a component of a structure (e.g., kyaku meaning “table leg”). In the context of hikyaku, however, it evokes first and foremost the legs in motion — covering hundreds of kilometers along rocky paths.

It is also important to distinguish hikyaku as the name of a specific profession from the more general notion of a messenger. Japan had many forms of message transmission — from local tsūshin-nin (通信人), or ordinary urban runners, to imperial envoys known as shōshō (少将) in the Heian period. Hikyaku, however, is a term that became widespread in the Edo period and signified not just a function — but an entire specialized craft of communication: a systematic, extensive profession of couriering, with defined routes, relay stations, rules, and hierarchies. This was no one-time runner, but a person embedded in the bloodstream of Tokugawa Japan.

That is why when we hear the word hikyaku, we do not think merely of someone running with a letter. We think of a network, of a pulsing system, of someone who, through their body and perseverance, built the unity of a vast country. “Flying legs” that moved the heart of Japan — day by day, letter by letter.

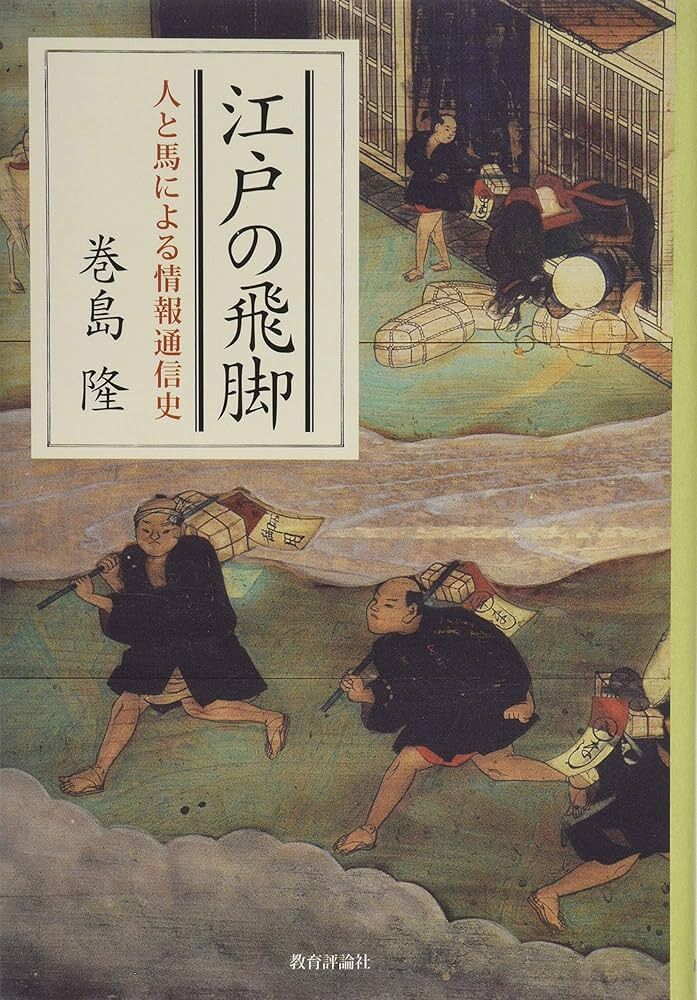

The History of the Hikyaku — From the Imperial Court to the Commercial Market

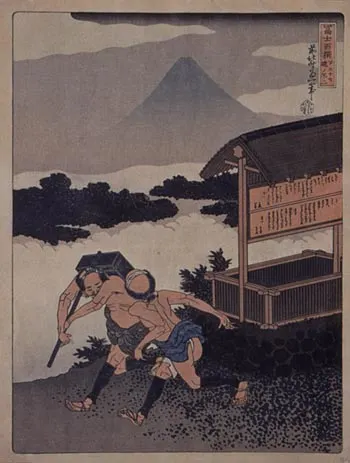

When the Kamakura period arrived in the 13th century, and the shōgunate assumed real power over the country (you can find more about these events here: What Does “Shōgun” Really Mean? One word that forged the Japan of samurai in steel and blood), couriers became the eyes and ears of the military government. The route from Rokuhara (the shōgunate's seat in Kyoto) to Kamakura — nearly 500 kilometers — could be covered by a well-trained hikyaku in just 72 hours. This near-miraculous feat was possible only thanks to a system of stopovers — relays, human and horse changes, rest points, and, above all, a powerful motivation: the courier risked his life, but served the shōgun himself.

Then came the Meiji era. The year 1871 brought the reform that ultimately sealed the fate of the couriers: a modern postal system was established, modeled on Western systems. A network of post offices, trains, and mailboxes spread across the country with unprecedented speed. The hikyaku, with their bells, staffs, and lacquered boxes, began to disappear from the roads. Some found employment in the new postal service, others left behind a profession that for centuries had been synonymous with resilience, speed, and service.

Yet the echo of their footsteps has not vanished completely. Modern courier companies like Sagawa Express proudly draw on their symbolism. The mascot Hikyaku-kun reminds the Japanese today of a time when a letter was not just a message — it was a bond, a relationship, a risk, and a mad dash across all of Japan with one’s soul on one’s shoulder.

The Organization and Operation of the Hikyaku

How did the world of Japanese couriers function?

How did the world of Japanese couriers function?

Today, when we picture a courier, we imagine a driver in uniform, with a handheld scanner and a van full of packages. But in the Edo period, in a land scented with cypress and damp pine, a courier was something far more than a delivery person. He was a living link in a network that enveloped the entire country — running through mountains, across bridges, along rice field paths and cobbled roads. He was a word in motion, an invisible connector between the provinces and the capital, between the heart of the country and its peripheries. The entire system operated thanks to exceptional organization and flawless coordination, whose precision would be the envy of many a modern logistics company.

The Foundation of Hikyaku Operations: The Ekiden Relay System

The foundation of hikyaku operations was the relay system known as ekiden (駅伝 — literally “station transmission” or “relay relay”), which dates back to the Nara period and was adapted by the Tokugawa shōgunate with remarkable effectiveness. Along the main routes — such as the Tōkaidō, Nakasendō, or Kōshū Kaidō — every few ri (1 ri ≈ 3.9 km) there were exchange stations for men and horses, known as tsugitate (継立 — literally “stand and pass on”). It was there that a courier could rest, hand over a letter to the next person in the chain, and continue without losing precious time. This entire network was managed by the sairyo (差配 — literally “one who assigns deliveries”) — an unassuming man, often residing in a modest house, but responsible for the punctuality and safety of both private and state shipments, small and large.

Depending on their type and function, hikyaku were divided into many specialized categories, each playing a distinct role within society.

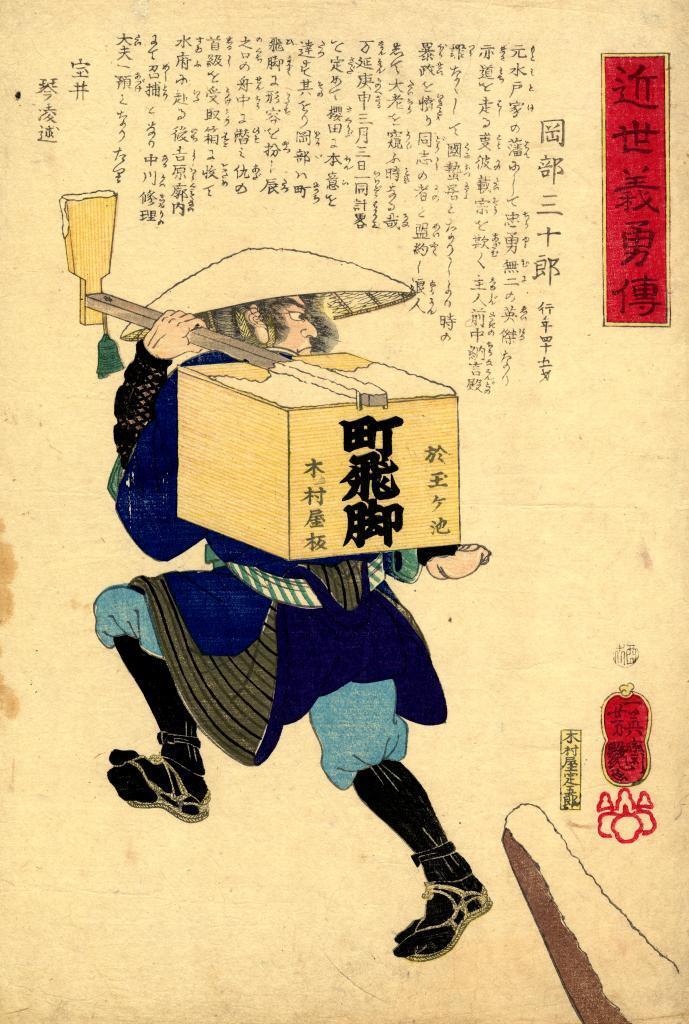

Alongside them operated the daimyō-hikyaku (大名飛脚) — private couriers of powerful feudal clans. These envoys were often dressed in the colors of their clan, and their task was to maintain contact between the Edo residence (where the daimyō were required to reside every other year, in accordance with the sankin-kōtai policy — more on that here: What to Do with a Society of Samurai Who Only Know War and Death in Times of Peace? - The Clever Ideas of the Tokugawa Shoguns) and their native province. Their networks were independent and well-organized — for example, the Tokugawa clan’s hikyaku from Wakayama departed from Edo precisely on the 5th, 15th, and 25th of each month, and from Wakayama on the 10th, 20th, and 30th. Each of them had stops every seven ri, hence their alternative name: shichi-ri-hikyaku (七里飛脚 — “Seven-ri Hikyaku”).

There were also couriers with even more personal roles — the tooshi-hikyaku (通し飛脚 — “direct” or “non-stop”), who traveled the entire route without relays. These were elite runners — strong, well-trained, moving non-stop for hundreds of kilometers. Their service was associated with the highest priority (and secrecy) of deliveries — they could deliver a message from Osaka to Edo in as little as 2–3 days. Their fee was high — even 8–9 ryō, equivalent to a year’s earnings for an average craftsman.

A unique type was the kome-hikyaku (米飛脚 — “rice couriers”), who specialized in transmitting information about rice prices on various exchanges. For merchants and speculators, such knowledge was priceless, so these couriers were given special protection and often escorted.

Delivery time depended on the type of service. Standard transport from Osaka to Edo took between ten and twelve days, but express shipments — handled by haya-hikyaku — could arrive in six, five, or even three and a half days. Record-breaking deliveries were completed within two days — naturally for an appropriately high fee. The cheapest delivery cost only a few dozen mon, while a direct service could cost the equivalent of a brand-new silk kimono.

Despite these dangers, hikyaku took pride in their role. Their speed, discipline, and quiet dedication made them legendary. Although their world has long since passed, the steps of these “flying legs” still echo in Japan’s memory — in street names, festivals, and courier company logos that nostalgically draw from their symbolism.

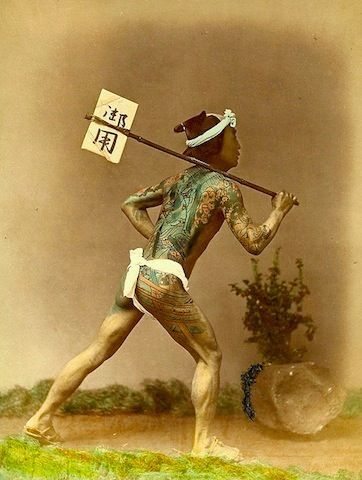

Clothing, Style, and Running Techniques

That is why, along the main travel routes, there existed hikyaku-yado — inns for couriers, where they could rest, eat, change their sandals, repack their boxes, and sometimes hand over the delivery to the next person in the chain. The relationships between couriers and local people varied — they were respected for their endurance and discipline, but were also sometimes seen as noisy messengers disrupting the order. At night, during stopovers, a hikyaku could also become a source of news and gossip from distant provinces, serving as an informal transmitter of culture and current events.

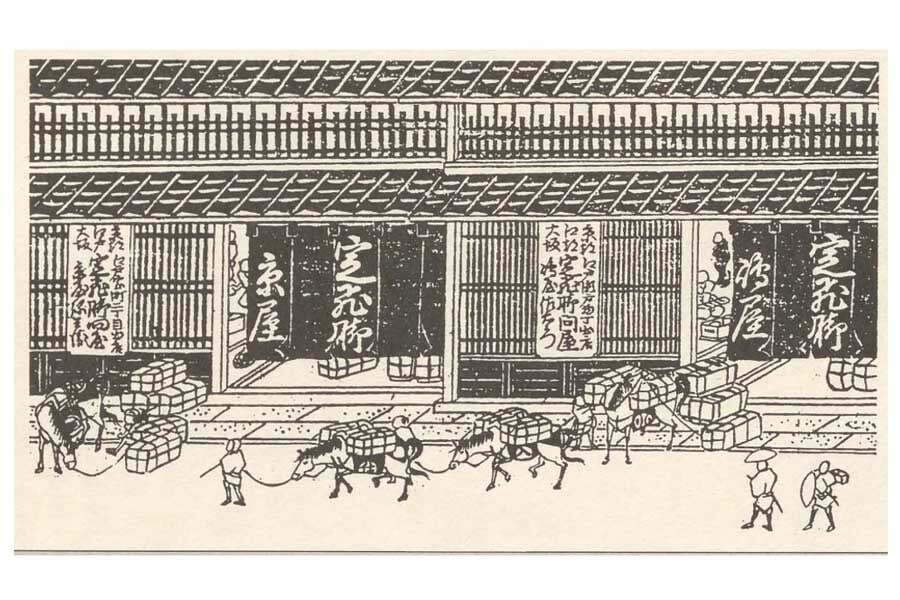

Courier Business in Edo

One of the most famous companies was Jūshichiya, founded in the 17th century, which for generations operated along the routes from Osaka to Edo, competing with the official bakufu postal system. Their operation was flawlessly organized: couriers departed three times every ten days, had designated rest points, fixed routes, and everything was overseen by a sairyo (manager) responsible for the safety and punctuality of deliveries.

The shōgunate attempted to control this expansion, regulating the routes, speeds, and privileges of courier companies. But the market showed no mercy. Private entrepreneurs competed for clients with delivery times, service cost, safety, and their ability to handle complaints in case of delays. The faster and cheaper — the better. Thus emerged the hayahikyaku — super-express couriers, who for a few ryō could deliver a letter in two or three days, running even through the night, through storms and mountains.

As a result, hikyaku became not only heroes of the road but also symbols of Edo-period “capitalism” — steadfast, clever, risk-taking. The flying legs of Japan — who carried not only messages, but bound the country together long before the railway did.

Between Drama and Comedy – Hikyaku in Literature

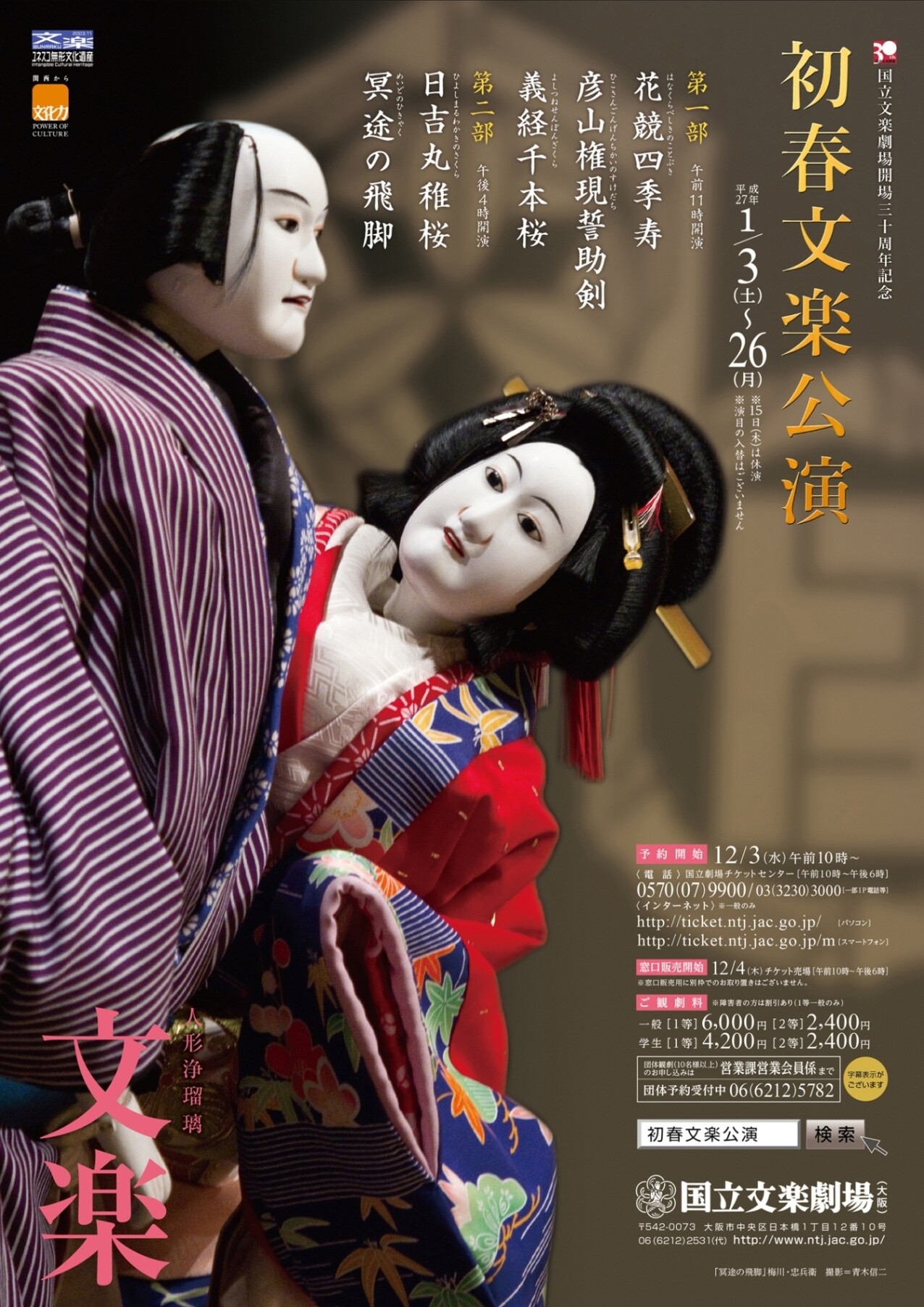

The most famous literary echo of this profession is without doubt the play Meido no hikyaku (冥途の飛脚) by Chikamatsu Monzaemon, the “Japanese Shakespeare,” first staged in 1711. The title can be translated as “Courier to the Afterlife” — and it is not merely a poetic metaphor. It tells the tragic story of the courier Chūbei, who falls in love with the courtesan Umegawa and, in an act of desperation, uses money deposited by a client. Though his feelings are sincere and his actions driven by passion and despair, he ends up a criminal — and his run becomes a literal journey to hell. The play not only explores the boundary between duty and emotion but also reflects the social pressure that weighed upon the hikyaku — who were personally responsible for every entrusted delivery, with their own lives as collateral.

On the other hand, Edo society loved to laugh at everyday life — which is why couriers also appeared in rakugo, the traditional Japanese form of stand-up storytelling. There, they are portrayed as talkative, absent-minded, soaked in rain, and entangled in comic misunderstandings — like the courier who mixes up two similar love letters or runs across half of Japan to deliver an empty envelope.

The memory of hikyaku has survived in modern culture as well. In the 1949 film Tengu Hikyaku (天狗飛脚), they are portrayed in an almost mythical way — as titans of endurance, with superhuman abilities reminiscent of the legendary tengu. Their echo can also be seen in anime, where characters dashing with messages wear costumes styled after the Edo period, and in video games — such as Ghost of Tsushima, where a network of informants and couriers plays a key role in the covert resistance against the Mongol invasion.

Finally, in today’s Japan, one can visit theme museums like the Nihon Hikyaku Rekishi-kan (日本飛脚歴史館) in Gifu Prefecture, where lacquered courier box replicas, detailed maps of historical routes, and authentic waraji sandals — worn through after just a few days of running — can be seen. In such places, hikyaku cease to be mere figures of legend — they become once more men of flesh and sweat, who connected the world long before the telegraph did.

Hikyaku Today

Hikyaku also return in another form — ultramarathons and long-distance runs, where some runners deliberately train in the old nanba-bashiri style, moving in harmony with their breath and body, avoiding excessive movement, and listening to the rhythm of their own waraji. This style, forgotten for decades, is returning today as an alternative to modern running techniques — though its actual health benefits remain subject to debate.

But perhaps the most enduring legacy of the hikyaku lies not in running, but in values. The couriers of old did not merely carry parcels — they carried trust. Their bodies were tools, but their currency was reliability. They ran through rain, mud, mountains, and rivers, knowing that the letter contained not only words, but the hearts of those who sent them. Their discipline — often stricter than that of the samurai — and their humility toward the entrusted task made them more than mere cogs in the machinery of old mail. They were the bloodstream of the nation, and their spirit — responsible and attentive — may still serve as inspiration in a world overwhelmed by noise and haste.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Machiya: What Were the Townhouses of Edo Like? – The Lives of Ordinary People During the Shogunate

Sentō Bathhouses in Shogunate-Era Japan – Dense Steam, Quiet Conversations, the Scent of Damp Pine

Poetry with Sake – Master Senryū and His Joyfully Malicious Insight

The Brilliant Eccentricity of Itō Jakuchū – Discover One of the Eccentric Painters of Edo Japan

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

How did the world of Japanese couriers function?

How did the world of Japanese couriers function?