Under the Watchful Eye of the Neighbor: Gonin gumi and Collective Responsibility in the Time of the Shogunate

The source of the modern Japanese neighborhood mindset

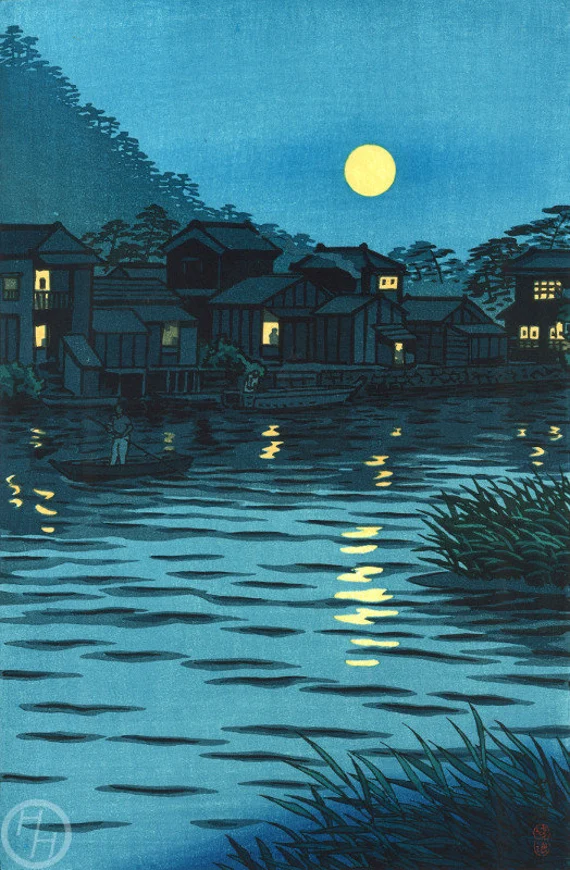

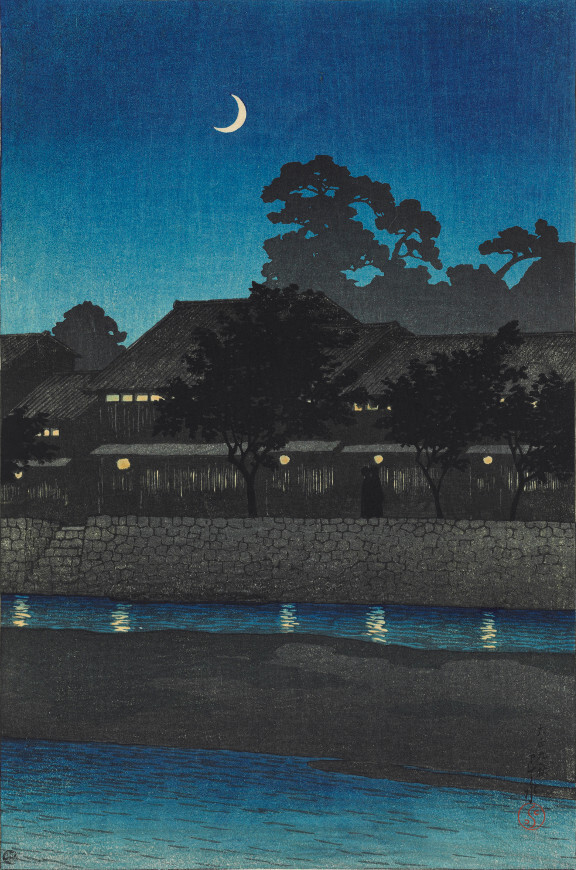

A scene from the life of a gonin gumi

Evening in the countryside

In the house of the kumigashira—the head of the local gonin gumi—a hibachi steamed in the very center of the guest room, the zashiki. The host’s wife placed cups of hot bancha tea before the guests as the other members of the group stepped over the threshold. Five men, each representing his family, sat in a circle on the tatami. They had met here many times before—for years they had together formed a gonin gumi unit, a five-household group of collective responsibility established by the Tokugawa shogunate to maintain order among its subjects.

“Gen’emon,” began the kumigashira, straightening his back, “you know the law of renpō sekinin (連方責任—principle of collective responsibility) is absolute. The nanushi will ask why we did not inform him about the guest. We will all pay for this.”

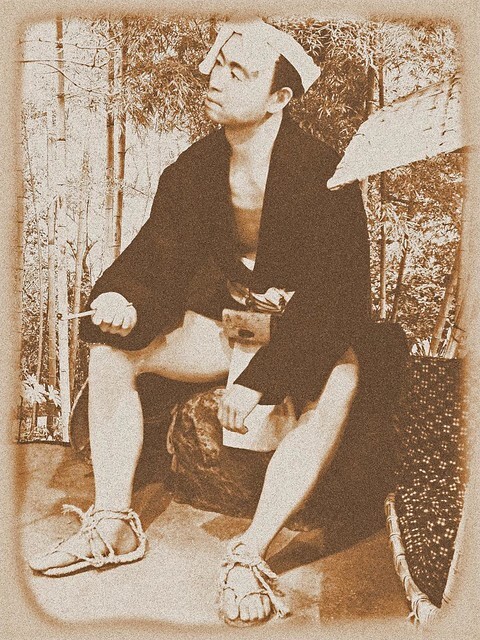

Gen’emon lowered his gaze, running his fingers along the frayed edge of his sleeve. “It was my cousin from the neighboring village,” he muttered. “He was late, and the night was cold… I didn’t want him to sleep in the fields.”

“And that is precisely why gonin gumi exists,” said another head of household, Hachirōbei. “So that such matters are reported, even if it’s about relatives. If the nanushi decides we were hiding a rōnin—we’re finished.”

“The nengu must be paid,” the kumigashira added. “If not by you, then by us. And then we will come after you for every mon, because there’s no other way. No one here wants goningumi hazushi, but you know…”—he broke off meaningfully, looking straight into Gen’emon’s eyes. Hazushi… Being expelled from the group meant not only shame but also practical exclusion from community life—no help during inekari (稲刈り—rice harvest), no support in illness, virtually no possibility of selling rice—and as a result, often—the loss of one’s livelihood and the risk of starvation for oneself and one’s family.

After a longer exchange, in which old cases of similar offenses were recalled, a decision was reached. They would jointly contribute the missing part of the tax. In return, Gen’emon would commit to repaying the debt through spring fieldwork for each member and—most importantly—would report any guests to the nanushi immediately upon their arrival.

The meeting concluded. The departing household heads adjusted their straw mino cloaks, while the cold evening air mingled with the smoke of hearth fires and the aroma of soy-based dashi wafting from nearby homes. In the quiet footsteps along the muddy street lay a silent understanding: in the Edo period, the survival of the community outweighed individual choices. Gonin gumi—though sometimes harsh—was the invisible web that bound together the lives of people in this orderly yet watchful Japan of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Origins of the gonin gumi system

By the late 16th century, this idea reappeared in a new form. In 1597, 豊臣秀吉 (Toyotomi Hideyoshi), who ruled over a unified Japan, introduced the gonin gumi as a tool for tighter control over the population. The aim was to limit vagrancy, monitor the lower ranks of samurai and peasants, and eliminate the threat posed by masterless warriors—浪人 (rōnin), whose numbers had risen dramatically after the end of the wars. The gonin gumi was also intended to prevent the sheltering of criminals, fugitives, and rebels. In each group of five households, all members were accountable for each other’s actions—forcing vigilance over one’s neighbors and strengthening local solidarity, but also creating a constant atmosphere of mutual surveillance.

The political context of this institution was clear: the gonin gumi formed the lowest link in the elaborate pyramid of Japan’s feudal authority. The Tokugawa bakufu sought to maintain peace (sometimes called by European historians “pax Tokugawa,” in reference to the “pax Romana”), social stability, and absolute control over its subjects—not through large-scale military force, but through a dense network of local mechanisms of social control. Within this network, the gonin gumi functioned like a “microscopic bakufu”—five households that kept watch over each other, resolved minor disputes, maintained the moral discipline of residents, and were collectively accountable to their superiors.

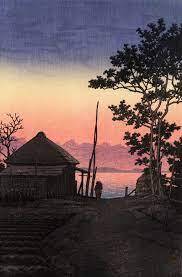

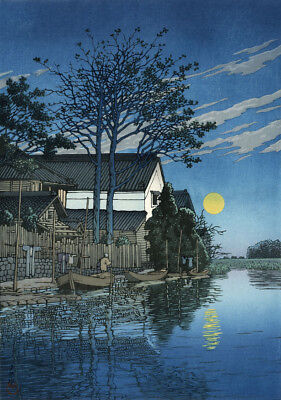

A scene from the life of a gonin gumi

Evening in the city

In a narrow lane, where the wooden walls of houses had already acquired a grey patina from moisture and salty air, five heads of household had gathered in front of the home of the kumigashira—the head of the local gonin gumi. According to Edo’s administrative structure, their gonin gumi answered to the nanushi (neighborhood chief), who in turn reported to the machi doshiyori (town elders), acting on behalf of the machi bugyō—the city magistrate of the shogunate bakufu.

Today’s meeting had not been planned, yet everyone came without delay, for in their system of collective responsibility (renpō sekinin), a lack of response could mean punishment for the entire group.

Tsuchiya Ichizaemon slid the tea bowl aside and lifted his gaze to those assembled. In the lamplight, the faces of the heads of household were greyed by smoke and fatigue after a full day’s work. Besides himself, there sat: Shimizu Denbei—a nori seaweed vendor from the market, Kanda Jinzō—a fisherman, Matsui Kihachi—a ship carpenter, and the eldest among them, Gorozaemon, who had long made his living repairing bamboo baskets.

“Minasan…” began Ichizaemon slowly, running his hand over the smooth paper of the gonin gumi chō. “Word has reached me from nanushi-sama. There is suspicion that our group has violated the regulations…”

The heads of household glanced at each other. Narrow street, nagaya after nagaya—here everyone saw what was happening at their neighbor’s home.

For a moment, the only sound in the room was the crackling of charcoal in the hibachi. Matsui lowered his eyes.

“It’s my nephew’s workshop,” he said at last. “He lost his place near Asakusa-bashi and moved temporarily to my house. He works carefully, keeps no fire…”

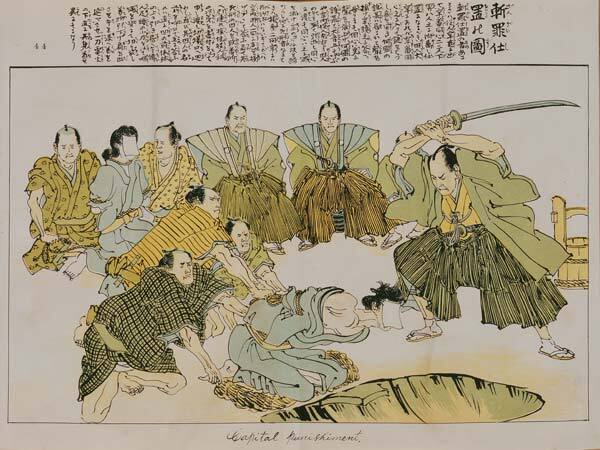

Ichizaemon reached for a bamboo pointer and touched it to the register. “Matsui-san, you know what this means. If there’s a fire, they will punish us all. It could be tsumi-kōfuku (collective punishment), or worse—goningumi hazushi for you. And if a samurai suffers losses—they might have us all beheaded…”

Silence fell over the room. Beyond the paper shōji partition came the clatter of geta from passing pedestrians and the distant calls of tofu sellers.

“I propose a solution,” Ichizaemon said at last. “By the end of the week, we will move your nephew to a workshop in shinmachi, where there is space for lacquer workers. We, as a gonin gumi, will oversee the move so that nanushi-sama knows we are acting together.”

Matsui nodded, though shame and worry filled his eyes. “Agreed. I don’t want the group to suffer because of us.”

The meeting ended in accordance with ritual—each man pressed his seal to a short note, which Ichizaemon would deliver to the nanushi in the morning. Outside, the air had grown heavy with dampness from the river, and on the darkening sky, crows wheeled over the slumbering port.

The workings of the gonin gumi

Organization

Organization

Although the name 五人組 (gonin gumi) literally means “group of five people,” in practice it did not always consist of exactly five households. In records from different parts of the country, units can be found ranging from as few as three to as many as eleven homes. In cities, gonin gumi were often formed based on the compact layout of nagaya—long row houses in which individual rooms functioned as separate households. In the countryside, groups comprised neighboring farmsteads within one or several aza (sections of a village).

The composition of a group depended on location. In rural areas, most members were 本百姓 (honbyakushō)—owners or tenants of farmland who held the formal right to cultivate fields and pay the rice tax (nengu). In Edo, Osaka, or Kyoto, members were primarily 家持 (ie-mochi), meaning homeowners, regardless of whether they lived in their houses themselves or rented them out to craftsmen or merchants. Tenants, apprentices, and hired laborers were not formal members, though they were subject to the group’s rules through their landlords.

The administrative hierarchy in the Tokugawa system

At the head of the gonin gumi stood the 組頭 (kumigashira)—the leader of the group. His role was crucial: he convened meetings, kept records, ensured the execution of the nanushi’s orders, and resolved minor disputes between members before they could escalate. The method of choosing the kumigashira depended on the region and local tradition. In some places, it was a hereditary position within one family, with duties passed from father to son. In others, a rotation system was used—each head of household held the role for a set period. There were also appointments made from above, by the nanushi or the elders.

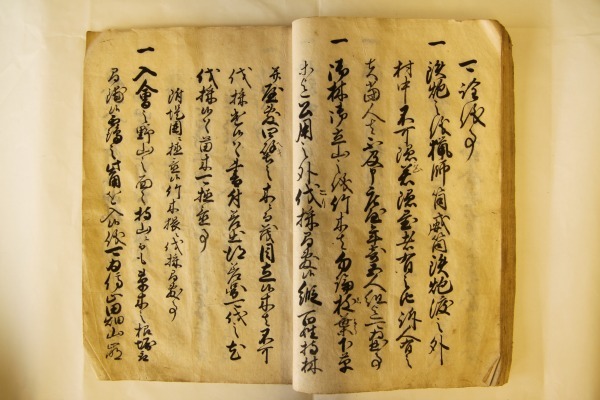

Numerous examples of gonin gumi-chō have survived in Edo-period archives. In addition to member lists, they contain notes on violations, decisions made at meetings, and receipts for tax transfers. These records reveal how meticulously—and how minutely—the bakufu and local authorities supervised the daily lives of residents.

Rules of operation of the gonin gumi

The gonin gumi system in the Edo period was not merely a dry entry in an official register—it permeated the daily life of townspeople and villagers alike, regulating matters of both security and interpersonal relations. Its principles rested on a tight link between loyalty to the state and obligations toward one’s own community.

Mutual responsibility – renpō sekinin

Mutual responsibility – renpō sekinin

The foundation of gonin gumi operations was collective responsibility. If any member committed an offense—whether theft, fighting, harboring a runaway peasant, or even a minor breach of domain regulations—the entire group could be punished. Responsibility also extended to tax obligations: failure by one head of household to pay the nengu (rice tax) forced the others to jointly cover the debt. The authorities believed that neighborhood pressure was more effective than a distant bureaucratic apparatus.

The duty to report – mikata no go-shinjō

One of the most uncompromising obligations was the requirement to report all suspicious behavior and individuals. This applied especially to the detection of Christians (キリシタン, Kirishitan), whose religion had been banned since 1614. The kōsatsu procedure—public proclamation of edicts—made it clear that concealing information about a “suspect faith” was a crime. The gonin gumi was also required to monitor travelers, including masterless rōnin, and to report unusual transactions or gatherings. In practice, this created a web of mutual surveillance, where a neighbor’s silence could determine the fate of the entire group.

Control of mobility – dekasegi kinshi

Control of mobility – dekasegi kinshi

Movement beyond one’s own domain (han) was strictly controlled. Travel to work in another province, or even to a nearby mine or port, required permission from local authorities. Members of the gonin gumi were obliged to ensure that no one in their group left their place of residence without the proper travel permit (tegata). This was in line with bakufu policy, which aimed to limit population migration and maintain tax order.

Ban on harboring suspicious guests

The regulations strictly defined who could be given shelter under one’s roof. Housing a stranger without travel documents (tegata) was prohibited. The only exception was for couriers on official duty—these could be accommodated after verifying their waybills or seals. Any deviations from the rules had to be reported immediately to the nanushi or the machi bugyō.

System of sanctions

System of sanctions

Penalties for breaking the rules included not only fines and compulsory public labor, but also the harshest form of social stigma—goningumi hazushi. A person expelled from the group lost the protection of the community: neighbors would cease to help them, no one would sell them goods on credit, and in some places even speaking to them could be considered a breach of local custom. Such ostracism was often more devastating than the financial penalty itself.

Community functions

The gonin gumi also served integrative functions. Groups were obliged to take part in public works: repairing roads, bridges, and embankments; cleaning canals; maintaining temples and fire watch stations (hikeshi-goya). In towns, they took part in preparations for matsuri—local festivals—funding work on portable shrines (mikoshi) and street decorations. These duties were meant to strengthen the sense of belonging but also provided practical support for maintaining infrastructure and public order without requiring additional government resources.

In this way, the system made the gonin gumi both an instrument of state control and a vehicle for local mutual aid—two functions so tightly interwoven that in the lives of Edo-period townspeople and villagers under Tokugawa rule, they were difficult to tell apart.

The social and psychological role of the gonin gumi

Local variants of the system also existed. In the Ryūkyū Kingdom (more on this here: Kingdom of Ryūkyū: Where Karate Was Born, Religion Belonged to Women, and Longevity Was the Norm), subordinated to the Satsuma clan, five-household units were adapted to the island settlement structure. In “old” villages (kyū-mura), gonin gumi were based on multi-generational bonds and traditional authorities, while in “new” villages (shinden)—established on land reclaimed by the Satsuma clan—they served more technical functions, supervising irrigation systems, water distribution, and the integration of newcomers. In every variant, however, the mechanism was the same: a combination of formal mandate with a strong network of local interdependencies, where fear of isolation (goningumi hazushi) and loss of face worked just as effectively, or even more so, than a shogunal edict.

The end of the gonin gumi

Paradoxically, the idea of collective responsibility and local oversight of the community was revived in a completely different era—during World War II. The tonarigumi (隣組)—mandatory neighborhood organizations established at that time—drew on the old goningumi model, though their function was more heavily subordinated to wartime mobilization, rationing of goods, and political control.

From a philosophical and cultural perspective, the gonin gumi are a pure example of the practical application of Confucian ideals—social hierarchy, the priority of harmony (wa) over individual needs, and the conviction that order arises from clearly defined relationships of duty and subordination. At the same time, their history reveals a universal dilemma: how far one can go in restricting individual freedom in the name of community safety. Such a system will certainly be less appealing to us—Europeans who cherish our freedom above all else. Yet we should not rush to judge—let us remember that this was an entirely different world. A different time, a different planet, and a different galaxy. And when we judge something, we do so through the lens of very specific values—in this case, for example, Western values of the 21st century. Values from an entirely different reality, another dimension.

Although the world of Edo is gone forever, many patterns of thought and behavior shaped over centuries—the sense of uchi, the fear of losing mentsu, and the role of uwasa as a tool of control—still resonate in 21st-century Japan. In this sense, the gonin gumi are not merely a historical curiosity from the pages of textbooks—they are one of the keys to understanding the enduring foundations of Japanese social culture. For anyone who seriously wishes to embark on a journey toward understanding Japanese culture, the gonin gumi are one of the essential stops.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Not the right smile, not the right pause. The grammar of silence in Japan’s high-context culture

Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era

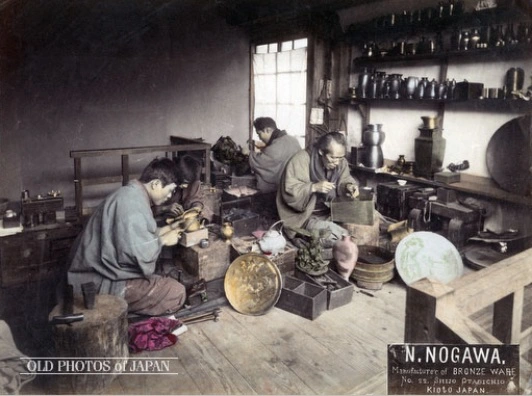

An Hour of Complete Focus – What Can We Learn from Traditional Japanese Craftsmen, the Shokunin?

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Organization

Organization Mutual responsibility – renpō sekinin

Mutual responsibility – renpō sekinin Control of mobility – dekasegi kinshi

Control of mobility – dekasegi kinshi System of sanctions

System of sanctions