Omoiyari and the Culture of Intuition – The Deepest Difference Between the European and Japanese Mindsets?

Kuuki wo yomu – “reading the air”

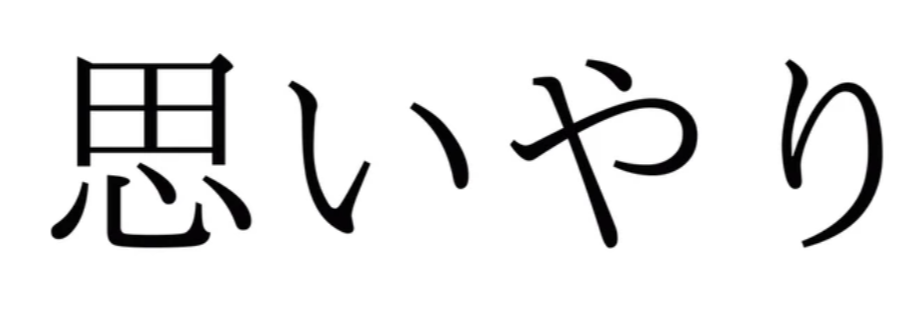

What does “omoiyari” mean?

The Meaning

The word omoiyari (思いやり) consists of two components:

- 思 (omoi) – means “thought,” “feeling,” “care.” This character expresses the act of thinking about someone or something, often with emotional overtones (the character contains the radical for heart, 心, at the bottom).

- やり (yari) – is a derivative form of the verb yaru, which in this context takes on the meaning of “to give” or “to offer.”

However, as a concept in its own right, omoiyari gained significance and systematic recognition in the modern era, especially after World War II, when the Japanese education system began to emphasize moral and social values. In the 1950s and 60s, omoiyari became one of the pillars of child-rearing—a tool for building a society based on harmony and shared responsibility rather than conflict or confrontation.

Usage in Contemporary Language

The concept also exists in close relation to other terms deeply embedded in Japanese mentality:

- 察し (sasshi) – intuition, perceptiveness. This word emphasizes the importance of sensitivity to the nuances of non-verbal communication—the ability to draw conclusions from silence and gestures.

- 迷惑をかけない (meiwaku wo kakenai) – “not causing trouble to others.” A fundamental element of social etiquette, this principle complements omoiyari as concern not only for others’ needs but also their comfort.

- 優しい (yasashii) – gentle, kind, mild. While not synonymous with omoiyari, yasashisa is often its outward manifestation—through voice, gesture, and demeanor.

Omoiyari – Psychologically?

Cognitive psychologists often divide empathy into two components: emotional (feeling what another feels) and cognitive (understanding what another feels). In the Japanese understanding of omoiyari, a third dimension is added—action. A small gesture, a sense of timing, a silence that stems not from the absence of words, but from their superfluity. In this sense, omoiyari is not merely an emotional state but a way of being that permeates the entire social fabric.

This mindset is instilled from an early age. Research by psycholinguist Patricia Clancy shows that Japanese mothers model omoiyari for even very young children by “assigning voice” to others. When a boy is eating a mandarin orange, the mother might say, “The girls are saying they’d like to have some too,” even if none of them said a word. The child learns that the feelings of others exist even when unspoken—and that they should be responded to (before being expressed).

In practice, this means hundreds of small gestures: someone gives up their seat before you even ask. Someone doesn’t say they’re upset—but stops speaking to you, and you know what you did wrong. A colleague doesn’t ask how you’re feeling, but leaves a cup of tea or a piece of chocolate on your desk. Words here are unnecessary, and sometimes even inappropriate—too much verbalization can disrupt the delicate emotional balance forming between people.

Omoiyari is a form of silent presence, as if to say: “I see you. I feel you. I’m here for you, even if you don’t say a word.” And while in the Western world this may seem vague, passive, or even overly sentimental, for the Japanese it is one of the most active forms of communication.

Omoiyari in Everyday Life

Japan is a country where omoiyari is not an abstract ideal but a daily ritual—often so quiet and natural that it becomes invisible to locals. Yet for a foreign visitor, each such gesture, each small courtesy, can be deeply moving—precisely because no thanks are expected and no special attention is drawn to them. In this section, we’ll step into the ordinary days of Japan: onto the subway, into shops, offices, and the home kitchen table. It is there that omoiyari truly lives.

On the Subway…

If you get on the subway in Japan and hear only the hum of the air conditioner and the rattle of the tracks, it doesn’t mean the train is empty. It means everyone knows that shared space requires mutual care. Phones are in silent mode, conversations are rare and hushed. Young people, exhausted after work, often doze off—no one wakes them or pushes past them. Omoiyari is this silent agreement: “I won’t disturb you. I know you might be tired. I respect your presence.”

Cleaning Up After Oneself

In a Japanese restaurant, no one leaves a mess behind. The customer carefully arranges bowls on the tray, wipes the table with a damp napkin, pushes the chair back into place. Not because they have to. But because someone will come after them—and they want that person to feel comfortable. Children in schools clean their own classrooms from a young age—not as punishment, but as a lesson in responsibility and community. Japanese schools don’t hire janitors—they don’t need to. This is the daily practice of omoiyari—care not only for people, but also for shared spaces.

Otohime – “Sound Princess”

In women’s public restrooms, you’ll often find a button that plays music or the sound of flushing. This is the otohime, or “sound princess.” Why? To mask bodily sounds and spare embarrassment—not just for oneself, but for others present. It is a gesture of discreet concern that embodies the Japanese aesthetics of modesty and anticipatory delicacy—even in situations where many other cultures simply “don’t make an issue of it.”

A Gift Without Obligation: “Ki ni shinaide”

In Japan, gift-giving isn’t limited to holidays and birthdays—it’s also a way of expressing gratitude, sympathy, or joy at reuniting. Yet almost always, it is accompanied by the phrase: “Ki ni shinaide”—“Don’t worry about it,” “You don’t have to return the favor,” “It’s nothing special.” This is a clear signal: I give from the heart, not to settle a balance. Here, omoiyari reveals itself as a gesture of pure intention—without expectation, without calculation.

Omoiyari in the World of Services and Work

Japan is renowned for its top-tier customer service, but few notice that it’s not just about professionalism. It’s about the omoiyari mindset. The cashier sees that you already have several bags—she gives you a larger one so you can pack more easily. On a rainy day, she offers a plastic cover for your paper bag. When you buy something heavy, she sticks a soft strip onto the handle so it doesn’t dig into your hand. You don’t ask—she reads the situation.

Everyday Tenderness: Human Relationships

But what touches the most is omoiyari in private relationships—the ones that form the warmth of daily life. A colleague notices you seem down—after lunch, you find tea and a little chocolate on your desk (or something else you genuinely like—somehow, thanks to everyday observation, she knows exactly what that is!). No note, no words. At home, someone cooks the very dish you happened to crave that day—not because you asked, but because your housemate sensed you might want it. On the train, someone offers you a seat, but doesn’t make eye contact—so you don’t feel embarrassed. Sometimes a slight nod is enough. Sometimes it’s enough that someone doesn’t say anything, even though they could.

These are the moments in which Japanese omoiyari culture becomes tangible, warm, real. It requires no grand words, but teaches that true care needs no invitation—all it takes is an open heart and attentiveness.

The Shadow of Omoiyari – When Care Becomes a Burden

At first glance, omoiyari appears as a noble attitude—empathetic, attentive, discreet. Yet like any ideal, it casts a shadow. Care that was meant to bring comfort can become a source of tension. Intuitive kindness—an instrument of control. Silence—a trap. The culture of intuition, so deeply cultivated in Japan, carries a subtle risk: that sensitivity turns into obligation, and relationships into an endless guessing game.

What seems like harmless “reading the air” (kuuki wo yomu) can lead to misinterpretations. A person acts, convinced they know what the other needs… and yet, they are wrong. They meant well—but did poorly. Worse still, there’s no way to fix it, because everything happens without words. Assumptions leave no room for clarification. Communication is lacking, and with it—clarity. What was meant to be an expression of subtlety becomes a source of misunderstanding and frustration.

Pressure and Emotional Burnout

Japanese society expects omoiyari not only toward others, but also from oneself. With childlike ease, one learns: “Anticipate before someone asks.” But the older a person becomes, the more this command turns into a burden. When every relationship demands vigilance, intuition, and delicacy—there is no space to rest. A condition emerges that psychology calls empathy fatigue—the exhaustion caused by constant emotional attunement. When every social interaction becomes a test of sensitivity, a person can feel burned out, emotionally drained, deprived of the chance to simply be themselves.

Silence in Suffering

In a world where people are expected not to speak openly about their needs, those who truly need something often remain silent. They collide with tatemae—the facade of social conventions that prevents them from expressing their honne, their true feelings. Omoiyari assumes the other person will intuit. But what if they don’t? What if someone can’t read between the lines? Or worse—what if they’re not allowed to speak, for fear of disturbing the harmony?

The Paradox of Loneliness in a Culture of Intuition

The more silent and “delicate” relationships become, the more one is tempted to ask: are we truly close, or only imagining that we are? If every emotion remains unspoken, is the relationship real? If I can’t say I feel bad because you’re supposed to know—and you don’t—then who failed: you or I?

In Japan, loneliness often doesn’t stem from physical isolation, but from the lack of space for true expression. Even among people, even within family, one can feel alone—precisely because everyone is too polite to be honest.

Blurring the Line: Intimacy or Distance?

The paradox of omoiyari lies in the fact that it operates between intimacy and distance. On one hand, it makes us feel seen and cared for. On the other, it maintains a safe wall of unspoken words—one not everyone may cross. What seems like closeness may in fact be subtle detachment. Because if you never say what you truly feel, I don’t have to confront it. And vice versa.

Through European Eyes – Personal Reflections

None of this means that omoiyari is inherently negative. Like any ideal, however, it requires balance and awareness. For us Europeans, the concept is so foreign that—to be honest—it evokes at least mixed feelings, even in those who have fallen in love with Japan and its history. The author of this text and website, too, has often struggled to accept sasshi no bunka—the culture of intuitive guessing—as part of daily life.

There are things I love about Japan, things I admire, things I’m learning, and things I find interesting or neutral. There are also things I’m not fond of—like the kawaii and moe motifs—but they are part of everyday life, and one learns to tolerate them. Like many other things that are simply foreign. But omoiyari is an idea that can “get under your skin,” even for the most devoted Japan enthusiasts. One may feel like a barbarian among people with overly refined manners, or fear saying anything at all—for fear of either breaching a boundary, or saying aloud something that the other person was supposed to intuit. And if we speak aloud what was meant to be understood without words—we may deeply offend the other person. So, better to remain silent.

At other times, the frustration arises when someone “mothers” you—a grown man advising, helping, or caring for another grown man in ways that we, as Europeans, simply do not expect. We don’t want it. We don’t welcome it—for us, it feels intrusive, pushy, a restriction of our freedom, even infantilizing. But try saying that directly. You may wound so deeply that the relationship ends. What remains is a coldness like Hokkaido’s winter—and a distance measured in light years.

(Of course, the Japanese are usually aware that they are dealing with a foreigner and take that into account. But if the relationship is long-term, part of daily life—like at work—it’s easy to forget.)

These are the real cultural differences. Pink spiky hair or the extreme looks of gyaru ganguro are easy to deal with. The true challenge lies in the nuances of human relationships—the things hard to name, invisible at first glance. And it is these, more than anything else, that determine whether a person will truly find their place in a culture. Not the language. Not the clothing. Not customs like bowing.

The contextual nature of Asian cultures—Japanese or Korean—can be one of the most difficult things to adapt to for a European accustomed to freedom of expression. It’s not about what’s better or worse (because what would “better” or “worse” even mean in the context of cultures?), but about how willing a person is to suspend—or at least temporarily set aside—their own cultural values in order to learn to function within those that may be radically different.

Such experiences teach humility. And they make us appreciate all the more those Japanese individuals who successfully find their place in Western cultures—for surely, it is at least as difficult for them as it is for us to live in Japan.

What Can Omoiyari Teach Us?

Omoiyari is not so much an ideal as it is a map—subtle and intricate—leading through a world of Japanese sensitivity, attunement to others, mistrust of words, and a deep desire for harmony. It is a concept that can fascinate, but also exhaust; it can inspire, but also provoke resistance. For those of us raised in a culture of expression, verbalization, emotional openness, and the fight for personal space—it can be like a mirror that doesn’t so much show us Japan, as it shows us ourselves, in contrast to it.

Because omoiyari is neither better nor worse than Western directness. It is simply a different answer to the same universal human need—to be seen, appreciated, and cared for. Where we say: “Tell me what you need,” the Japanese respond with a gesture, a glance, a silence, a preemptive movement of the hand. Where we value authenticity, they value the avoidance of conflict. These are two philosophies of relationship—and I cannot say which one is better (though I know which one I prefer, because of the way I was raised).

Is it possible to reconcile these two worlds? Can one speak of their emotions and at the same time hear what remains unsaid? Can one live in such a way as to have the courage to speak—and also the ability to intuit? Perhaps it is precisely here that omoiyari may become not only a Japanese value, but a universal lesson.

Omoiyari reminds us of something deeply human: that everyone wants to be seen. That sometimes a single glance, silent presence, putting the phone away, or a cup of tea offered without asking is enough to make someone feel important. But also—that we shouldn’t be afraid to speak openly when silence hurts.

A culture of care is not born of perfection—it is born of conscious choice. And if omoiyari can teach us anything, it is precisely this: that between empathy and silence there is no chasm, but a path. And each of us can walk it—in our own way.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Japanese Art of Silence – How the Concept of Silence Can Highlight Cultural Differences

The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

Kanji Characters: Hito and Jin – What Does It Mean to Be Human?

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!