Not the right smile, not the right pause. The grammar of silence in Japan’s high-context culture

Like a blind man with a deaf one

Like a blind man with a deaf one

馬の耳に念仏

(lit. “a nembutsu prayer into a horse’s ear”)

In Japan, a conversation may sometimes fall apart before a single word is spoken. Not due to a difference of opinion, but because someone made the wrong gesture, held eye contact for too long, reached for a hand too quickly, smiled too stiffly—or not stiffly enough. In Japanese culture, where communication is grounded in nuance and sensitivity, such small details can change everything—and we, visitors from the West, may not even notice that anything happened at all. This is a world where not only words, but also glances, pauses, and the positioning of hands carry meaning. Where an inappropriately performed gesture is like a false note in the music of silence—invisible to a foreigner, but jarring to a Japanese observer.

Between expression and self-censorship

The differences between Japanese and Western nonverbal communication are striking. While in Anglo-Saxon countries, direct eye contact signifies sincerity and strength of character, in Japan it may be seen as an act of aggression, a breach of personal space, or impolite insistence. That’s why many Japanese people look not into the eyes but at the neck area—signaling a readiness for contact without crossing an invisible boundary of privacy. Likewise, behaviors such as loud laughter, strong facial expressions of emotion, or broad gesticulation—valued in the West as signs of authenticity—may be viewed in Japan as lack of refinement or childish emotional immaturity.

Understanding Japanese body etiquette, then, requires more than memorizing a few gestures. It demands entry into a mindset where politeness is not about what we say, but about how not to infringe on someone else’s space—even with a gesture, even with a glance.

How is Japanese communication different from Western communication?

In low-context cultures, people speak directly: words carry meaning, and clarity and unambiguity of expression are considered virtues. Ambiguity, hesitation, or unsaid thoughts often lead to frustration and suspicion—because if someone didn’t say something, they must be hiding it. Meanwhile, in high-context cultures—like Japan—meaning is conveyed more through what is unspoken: through the atmosphere of the conversation, the social status of participants, their gestures, facial expressions, relationships, and shared experiences. Words are but a thin layer on the surface of a deep sea of meaning, which must be read intuitively.

From the standpoint of intercultural psychology, high-context culture fosters social harmony and conflict avoidance, but may also lead to excessive suppression of emotions and difficulty expressing individual needs. Conversely, low-context culture promotes directness and individual autonomy but may overlook subtle signals and hurt unintentionally through too much bluntness.

Understanding this difference is not just a matter of language, but a deep shift in perceiving communication as an act of mutual attunement—not merely information exchange. Only then do gestures like a hand to the forehead, an averted gaze, or palms pressed together in prayer reveal the full force of their cultural significance.

You can read more on this topic here: Japanese Art of Silence – How the Concept of Silence Can Highlight Cultural Differences

But today, let us focus solely on the language of the body.

Gestures of Bows and Posture

The Language of Hierarchy and Respect

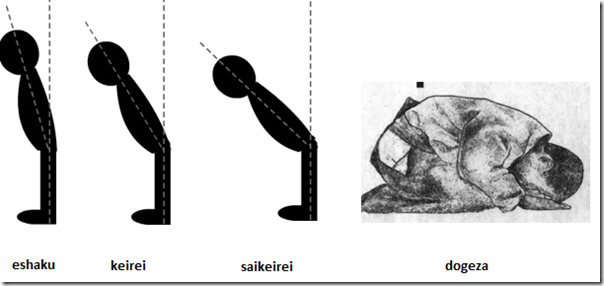

Bows: Eshaku (15°), Keirei (30°), Saikeirei (45–90°) – how to perform them, when to use them, what they mean

The bow in Japan is a form of nonverbal communication executed with remarkable precision—its depth, duration, and context convey an entire spectrum of intentions: from a casual greeting to the deepest of apologies. Eshaku, a bow at about 15°, is an everyday gesture seen on the street, in offices, or between acquaintances—it expresses kindness and basic respect. Keirei (approximately 30°) is a more formal bow—used in professional settings, in relations with clients or superiors. The deepest bow, Saikeirei, ranges from 45° to 90°, and is reserved for expressing remorse, gratitude, or reverence—such as during public apologies or ceremonial contexts.

Importantly, the bow in Japan is not a mechanical act—it is a gesture of conscious bodily control that carries a specific message. In a culture where words can easily intrude upon another’s space, the bow allows for the expression of respect without confrontation. Psychologically, it also serves a self-regulatory function—by bowing, the individual aligns themselves with the other person and the situation, giving due place both to themselves and to their interlocutor. It is a gesture that eases tension, clarifies hierarchy, and restores balance in the relationship.

Mokurei – the nod and eye contact

Mokurei – the nod and eye contact

目礼 (mokurei)—literally “eye bow”—is a nearly invisible gesture, yet highly significant. It involves a gentle nod and brief eye contact, without a single word being spoken. Used in situations where one cannot or should not speak (e.g., during a ceremony, a concert, a business meeting), mokurei is an expression of discreet politeness and acknowledgment of the other person’s presence.

Psychologically, mokurei embodies one of the most characteristic tensions of Japanese culture—the desire for recognition paired with the avoidance of excessive exposure. It is a gesture that says: “I see you and I respect your presence,” but does not impose or demand a response. It is a symbol of high-context communication—fully understandable only to those who know the rules of the game.

Hand position during a bow (at the sides, in front, joined)

Hand position during a bow (at the sides, in front, joined)

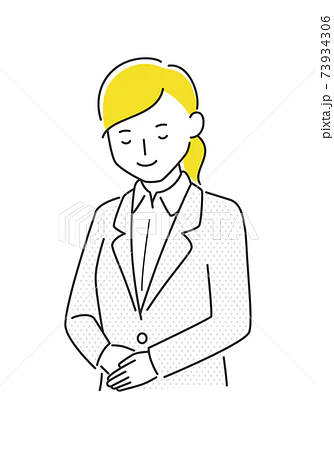

The position of the hands during a bow also carries specific meaning. In the basic, formal male version, the hands hang loosely at the sides of the body. In more ceremonial situations or in the case of women, the hands are gently joined in front, one resting over the other. In the service industry (e.g., hospitality, gastronomy), this form is mandatory—it expresses humility, readiness to serve, and respect toward the guest.

Interpreting this gesture, one can observe that hand position reflects the social role the person is assuming at that moment. Joined hands in front say: “I am here to serve you, I do not dominate the space.” Hands at the sides, on the other hand, convey confidence and neutrality. Regardless of the version, the key point is that the body must not “tower over” the interlocutor—neither literally nor symbolically.

Hands at the sides in formal posture (women vs. men)

Japanese etiquette also takes into account gender differences in posture. In formal position, a man stands with his hands along his sides, palms flat against his thighs, feet slightly apart. A woman, by contrast, stands with hands folded in front, feet close together. This difference stems from traditional social roles—the man as a figure standing firm and stable, the woman—modest and reserved.

Although these distinctions may seem archaic today, they are still upheld in many institutions, especially in ceremonial or corporate contexts. Their psychological function lies not so much in rigidly reinforcing gender roles, but in maintaining order, aesthetic harmony, and behavioral predictability—qualities that in Japan are seen as pillars of social cohesion.

Walking through a crowd with a “hand cutting the air” – “Chotto sumimasen”

Walking through a crowd with a “hand cutting the air” – “Chotto sumimasen”

In a crowded subway, at a festival, or on a busy street—the sight of someone moving through the crowd with a hand raised vertically, making a “cutting” motion through the air, is an everyday occurrence in Japan. This gesture—often accompanied by a polite chotto sumimasen (“excuse me for a moment”)—is not just a request to pass, but an act of social self-regulation in shared space.

An interesting aspect of this gesture is its almost ritual form—the arm does not move chaotically, but makes a calm, rhythmic motion. Psychologically, it serves to lower situational tension—the gesture itself signals that the person does not wish to invade others’ space, but must momentarily do so. It is a form of communication: “I am here, but I am not barging through; I am only crossing your space with full respect.” And it is precisely here that the Japanese mastery of blending the need for action with the etiquette of respect and empathy reveals itself.

Facial and Hand Gestures

Embarrassment, Remorse, Politeness

Embarrassment, Remorse, Politeness

Japanese nonverbal communication often takes place on a microscale of gestures that, in Western culture, might go unnoticed or be misread. A movement of the hand, a subtle shift of the gaze, the folding of fingers—all of these can express inner tension, an attempt at remorse, or an emotional message too direct to be spoken aloud. This subtlety stems from a deeply rooted need to maintain social harmony and avoid confrontation—what cultural psychology refers to as affective regulation based on self-control and the implicit coding of signals (in plain terms: the suppression of emotions and conveying them indirectly—through gestures, tone, silence, rather than direct speech). Below are five typical gestures from this category—all commonly used, yet requiring a careful eye to grasp their full meaning.

Hand behind the head – embarrassment, awkwardness

The gesture of raising the hand and placing the open palm behind the head—often accompanied by a slight tilt of the head and a half-smile—is a classic sign of embarrassment or social awkwardness. In nonverbal psychology, it is classified as a “self-soothing” gesture, occurring when someone is in a socially challenging situation: having been praised, caught in a mistake, or unsure how to answer an uncomfortable question.

In the Japanese context, this gesture is sometimes used in place of the word “sorry”—but without the formality and emotional weight of a full bow. Unlike in the West, where a person might respond to awkwardness with nervous laughter or a joke, a Japanese person will opt for a gesture that diffuses tension while acknowledging weakness—yet without overt emotional expression. It is an act that simultaneously protects face (顔を立てる, kao wo tateru, literally “to raise one’s face”)—both one’s own and the interlocutor’s—allowing both parties to “exit the situation” without a loss of dignity.

Hand on the forehead or covering part of the face – apology, embarrassment

Hand on the forehead or covering part of the face – apology, embarrassment

Covering the forehead, eyes, or mouth with the hand is another gesture that, in Japanese culture, functions as an expression of remorse, shame, or embarrassment—most often in casual or social situations, more rarely in formal ones. Women often cover their mouths while laughing—not as a sign of inhibition, but rather as a culturally conditioned act of modesty and control over emotional expression.

This gesture reflects one of the fundamental principles of Japanese communication: enryo (遠慮), or restraint. Covering part of the face symbolizes a retreat of the self—a reduction of one’s visibility so as not to disrupt the situation, not to impose, not to cause discomfort. From the perspective of social psychology, this can be likened to a strategy of avoiding exposure to negative emotion, where the body takes on the weight of an unspoken “I’m sorry” or “it’s my fault.”

Hands pressed together in prayer-like form – asking a favor, “itadakimasu,” “sumimasen”

Hands pressed together in prayer-like form – asking a favor, “itadakimasu,” “sumimasen”

Bringing the hands together in a posture resembling prayer—with palms facing each other, usually at chest height—is one of the daily gestures of politeness in Japan. Though it resembles religious gestures, in practice it functions as an almost automatic cultural signal: “I’m sorry, please, thank you, I appreciate it.” Used in both trivial situations (“may I borrow your pen?”) and ritual ones (itadakimasu—giving thanks before a meal), this gesture expresses a conscious withdrawal of one’s will and acknowledgment of the other person as someone offering something valuable.

From an anthropological standpoint, this gesture can be interpreted as a remnant of ryōkai culture—of exchange and gratitude. Through the hands, one not only makes a request but symbolically creates a “space between”—a sphere in which relationship and recognition are born. Unlike the Western “please” or “thank you,” which are often spoken routinely, the Japanese gesture of folded hands engages the whole body—physically involving oneself in the relational act, not merely linguistically.

Pointing to oneself by touching the nose

Pointing to oneself by touching the nose

When a Japanese person is called upon—say, in class or during a conversation—they will often respond not with the word “me?” but with the gesture of touching the tip of the nose with the index finger. In Western culture, we identify ourselves by pointing to our chest—in Japan, the symbolic location of “I” lies at the center of the face.

This seemingly minor shift carries important meaning: pointing to the nose is not a dominant gesture—it’s not a show of strength, but a subtle admission of responsibility or presence. The touch of the nose is often accompanied by a slight bow or an expression of surprise—signaling modesty and, at times, a reluctance to be in the spotlight. In cultural psychology, this can be understood as a form of self-effacement—a strategy of minimizing oneself, which increases social acceptance.

Eye contact and its avoidance – humility, respect, or aversion?

Eye contact and its avoidance – humility, respect, or aversion?

One of the most fundamental differences between Japanese and Western nonverbal communication lies in the perception of eye contact. In Western—especially Anglo-Saxon—cultures, direct eye contact is seen as a sign of honesty, courage, and dignity. In Japan, however, prolonged eye contact may be perceived as intrusive, confrontational, or even aggressive—particularly in asymmetrical relationships (e.g., student–teacher, employee–superior).

Avoiding eye contact does not imply a lack of interest—it is a gesture of humility, acknowledgment of hierarchy, or care for the other person’s space. Often, the speaker looks toward the listener’s neck, while the listener lowers their gaze—creating a phenomenon of subtle contact choreography. Psychologically, this avoidance of eye contact does not stem from a lack of confidence, but from a normative cultural model that promotes harmony through non-invasiveness and indirectness.

In conflictual or tense situations, avoidance of eye contact may also express aversion or emotional withdrawal—but even then, it is not a gesture of hostility in the Western sense. Rather, it is a message: “I don’t want to escalate, I won’t look in order not to provoke.” This distinction is worth knowing so as not to misinterpret the intentions of a Japanese interlocutor—for in high-context culture, the most significant things happen precisely where the West sees… silence or absence. Or rather—doesn’t see, because it doesn’t look.

Gestures of Refusal and Boundaries

– How to Say “No” Without Words

In Japanese culture, the word “no” (いいえ – iie) does not appear in everyday communication as often as it does in Western cultures. This is not due to a lack of assertiveness, but rather a deeply rooted need to maintain relational harmony and avoid direct confrontation, which could threaten the interlocutor’s position or disrupt the atmosphere of group cohesion. Therefore, refusal in Japan is coded through gesture, tone of voice, hesitation, or suggestion—it is rarely expressed outright. In this context, body language plays a key role: it is the language of boundaries, disagreement, and reluctance—expressed without breaking the illusion of accord. Below, we examine five gestures that allow Japanese people to say “no”—gently, obliquely, but effectively.

Waving the hand in front of the face – “No, no,” “That’s not it”

This gesture, performed by quickly waving an open hand horizontally in front of the face, is often accompanied by a slight smile and phrases such as 「違う違う」(chigau chigau – “not quite, not quite”) or 「いやいやいや」(iya iya iya – “no, no, no”). In Japanese culture, this is the softest form of refusal, used in both social and professional contexts. It carries no aggression or finality—it is more of a suggestion: “I’m not sure that’s quite right,” “I don’t entirely agree,” or “That’s probably not what you mean.”

Psychologically, it is a tension-diffusing gesture—its purpose is not to set a hard boundary, but to create emotional distance in a safe way. From an intercultural perspective, it’s worth noting that this gesture is often misread by foreigners.

Arms crossed in an X – “Forbidden,” “Not allowed”

A far more unambiguous gesture is crossing the arms in front of oneself in the shape of an X, often performed with a serious or even stern facial expression. It is used in formal situations to indicate a clear prohibition or disagreement: “You can’t enter here,” “That’s not allowed,” “Stop.” This is the nonverbal form of dame! (だめ – forbidden, not allowed), commonly used by security guards, teachers, or officials.

This gesture signals a boundary that must not be crossed. Unlike the gentle hand wave, here the boundary is firm—yet still conveyed through gesture, not words. It is a form of nonverbal discipline rooted in the Japanese ethos of collective regulation, where “no” is not directed against someone, but exists to uphold a rule or standard.

Crossed index fingers – “Check, please” in an izakaya

This gesture—performed by crossing the index fingers at chest or face height—serves a more pragmatic than emotional function. It is used in izakayas, bars, and restaurants as a nonverbal request for the bill. Although the symbol (the shape of an X) in other contexts means “forbidden,” here it is understood as “closing the tab,” ending the situation.

This illustrates how deeply ritualized and gesture-based daily interaction is in Japan. Although the spoken phrase okaikei onegaishimasu (“check, please”) would be fully understood, many people choose the gesture—it’s quicker, silent, and avoids verbal intrusion into the mood of the gathering. It is also a subtle “no” to further ordering—a way to say “that’s enough” without offending the host.

Tilted head with hesitation – uncertainty, a quiet “no”

A subtle gesture of tilting the head to the side, often accompanied by the sound “んー” (n...), is a typical reaction to a question one doesn’t wish to answer with a direct negative. The person may look away or downward, sometimes with a faint smile—all to avoid saying “no,” while clearly implying that the answer is negative. This is not a sign of cognitive uncertainty (“I don’t know”), but of a strategic withdrawal from direct assertion (in the West, this may more often indicate doubt or suspicion—making it prone to misinterpretation).

Such behavior falls under the category of omotemuki—an outward-facing behavior focused on the other person’s emotions and preserving the relationship. In Western culture, a similar reaction might be seen as avoiding responsibility or a lack of decisiveness. In Japan, it is considered a sign of interpersonal sensitivity that acknowledges that sometimes one cannot speak directly—and it is better to “let the other person infer.”

Arms crossed (meaning: I’m thinking, but also: I disagree)

Crossing the arms over the chest is a gesture with universal connotations, but its interpretation is highly dependent on cultural context. In Western culture, it is most often read as a defensive or oppositional signal—a gesture of withdrawal, distance, and often a conscious stance against the interlocutor. A person with arms crossed may be perceived as disengaged, skeptical, or even hostile. In the West, this gesture is classified as a defensive posture: a physical “shutting down” of emotional or argumentative exchange.

In Japan, however, crossed arms function within a broader spectrum of meanings—and are not automatically understood as negative. In neutral contexts, with a calm facial expression and eyes downcast or closed, they often signify inner concentration, reflection, or deliberation. It is a subtle signal: “Give me a moment, I’m processing.” In tense situations, yes—they may also convey distance, inner disagreement, or resistance—but never in such an overtly confrontational way as in the West. The difference lies in the fact that Japanese communication is based on context, implication, and reading emotion from surroundings—so the meaning of this gesture is never fixed but is “read” according to the situation, relationship, and facial expression.

From the Japanese perspective, deeply rooted in a philosophy of relationality (e.g., influenced by Confucianism), crossed arms do not necessarily signal opposition to the other person—but rather the need to maintain a buffer between people. It is a gesture that balances the tension between honne (true feeling) and tatemae (social facade). A Japanese person with crossed arms is saying: “I hear you—but I’ll think about it on my own terms.” In contrast to the Western interpretation, which assumes emotional disengagement from the conversation, in Japan this gesture may be a form of quiet participation—a sign of emotional self-regulation and introspection in the presence of another.

This subtle but profound difference reveals just how divergent the body’s semantics can be in two cultures that, on the surface, seem to use the same gesture.

Relational and Emotional Gestures

Closeness, Irony, Distance

Among Japanese gestures, there exists an entire category of bodily signs that function as “emotional tools of communication”—used to strengthen bonds, signal distance, express self-irony, play with convention, or convey a hidden message. These gestures are often ambivalent in nature—playful and meaningful at once, polite yet laced with subtle innuendo. They differ from formal bows or gestures of refusal in that they operate at the intersection of informal, intimate, or emotionally charged communication. And though they may seem frivolous at first glance, they often touch on serious themes—gender, hierarchy, emotion, pride, or personal interest.

The “Pinkie”

One such gesture is the “pinkie finger”—raising the little finger while keeping the rest of the hand clenched. Though it may appear childish, in Japan this gesture has surprisingly unambiguous connotations: it signifies a woman—most commonly a girlfriend, wife, or sometimes a lover, depending on the context. Among groups of men, it can be used as an allusion to someone’s partner or to ask about their romantic life—without the need to verbalize anything. In the language of Japanese culture, this kind of unspoken bodily innuendo draws a delicate line between jest and social code.

Tengu no hana

Another gesture—humorous yet rich in meaning—is tapping one’s nose with a clenched fist (sometimes with one finger extended), known as tengu no hana—the nose of the tengu (天狗の鼻). In Japanese culture, the tengu is a mythical being known for pride and arrogance, recognized by its long nose—a symbol of vanity. The use of this gesture is thus a form of self-mockery—an acknowledgment of boasting or bragging, but in a controlled, playful way. In interpersonal contexts, it is also a means of easing tension: I’m showing that I know I’m bragging—so don’t accuse me of it.

The fist placed against the nose (sometimes with one finger extended) is a visual metaphor for the tengu’s long nose, representing inflated ego, pride, and vanity. This gesture is often used jokingly in conversation to tease someone—“Oh, someone’s showing off,”—but can also be self-directed, performed after receiving praise or a compliment. It’s not done aggressively but with a lightly theatrical flair—more a social commentary than an attack.

One must be cautious—graphics or gestures can be easily misunderstood. In the West, a long nose signifies a liar, “Pinocchio.” In Japan, it may mean someone boastful or with their nose in the air.

Sesame Grinder

A gesture known as the “sesame grinder” (surigoma)—a circular motion made by a clenched fist over the open palm—is a symbol of flattery or sycophancy. It originates from the act of grinding sesame seeds—symbolically, ingratiating oneself, literally “rubbing up” to someone. In group contexts (such as in the workplace), it can be used with a wink to comment on someone’s brown-nosing behavior. It functions as a form of cultural regulation over hierarchical relations—allowing behavior to be named without direct condemnation. In this way, the gesture serves as a social valve—enabling critique in a non-confrontational manner.

The “V” Fingers Gesture

The “peace sign” (the V-sign), so widespread in Japanese pop culture and photography, was not originally a Japanese invention—but it is Japan that turned it into a symbol of relaxation, youthful ease, and a light sense of distance. For older generations (in Japan, this can mean 90+), it may still seem somewhat childish, but for younger people (which in Japan can mean <60), it is a way to ease tension, especially in the presence of foreigners. Scholars note that the peace sign in Japan often serves to “mask” embarrassment in front of the camera—it is not just a gesture of joy, but also of hidden self-consciousness, a need to “do something with your hands” when feeling overly exposed.

“O” Made with Fingers

“Let’s Go for a Drink”

“Let’s Go for a Drink”

The gesture of mimicking the act of drinking from a cup or sake vessel—by bringing the hand to the mouth and slightly tilting the head—is a clear invitation to share sake. It is often used among friends, informal yet very common. It is a nonverbal cue to engage in drinking together—one of the most widespread rituals of building trust—both in Japan and in Poland. The topic of drinking with Asians, however, might require a separate article someday…

“Come Here”

The gesture of inviting someone over, performed with the palm facing downward and the fingers gently curling toward the body, is a subtle yet significant cultural difference that often surprises foreigners in Japan. Unlike the Western “come here” gesture—made with the index finger pointing upward—the Japanese version is more subdued, polite, and gentle. Its aim is not to command but to invite in a non-intrusive way, in keeping with the aesthetics of non-confrontational communication.

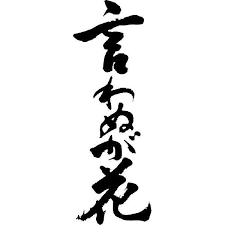

Learning a Language—Not Just Words and Writing

Gestures in Japan are like the strokes of a calligrapher’s brush—each has its place, its time, and its weight. Legible to insiders, invisible to outsiders, yet no less real. Their quiet power lies not in their effect, but in their alignment with the rhythm of social coexistence. And perhaps this is why it’s worth asking: is it truly wise to learn Japanese—or any language of a high-context culture—solely through characters, words, and grammar? Are we not making a serious simplification by treating such languages as if they belonged to the Western world—direct, almost entirely verbal? Are we not overlooking that which is quietest, and at the same time, most meaningful?

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Silence of Endless White – Winter Haiku as a Mirror of the Soul

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Like a blind man with a deaf one

Like a blind man with a deaf one

Mokurei – the nod and eye contact

Mokurei – the nod and eye contact Hand position during a bow (at the sides, in front, joined)

Hand position during a bow (at the sides, in front, joined)

Walking through a crowd with a “hand cutting the air” – “Chotto sumimasen”

Walking through a crowd with a “hand cutting the air” – “Chotto sumimasen” Embarrassment, Remorse, Politeness

Embarrassment, Remorse, Politeness

Hand on the forehead or covering part of the face – apology, embarrassment

Hand on the forehead or covering part of the face – apology, embarrassment Hands pressed together in prayer-like form – asking a favor, “itadakimasu,” “sumimasen”

Hands pressed together in prayer-like form – asking a favor, “itadakimasu,” “sumimasen” Pointing to oneself by touching the nose

Pointing to oneself by touching the nose Eye contact and its avoidance – humility, respect, or aversion?

Eye contact and its avoidance – humility, respect, or aversion?

“Let’s Go for a Drink”

“Let’s Go for a Drink”