The Samurai Rite of Genpuku – When a Boy Receives His Name, His Weapon, and the Fate of a Warrior

The Sudden End of Childhood

Everything that takes place in this moment is contained within two characters: 元 (gen) – beginning, origin, primal essence – and 服 (puku) – to clothe, to shoulder. The earliest genpuku ceremonies, performed in the Nara period as the Confucian kakan “donning of the cap,” resembled courtly coronations; but when the warriors took power, the gesture became clad in steel and blood. The soft kanmuri cap gave way to the hard kabuto helmet, and instead of the silk kariginu, boys donned gleaming dō-maru armor. From the Kamakura era onward, it was not a legal paragraph but the blade that determined the worth of a name. Genpuku thus became a symbolic threshold: a vow of loyalty to one’s lord, and simultaneously a license not only to kill, but to die with sword in hand.

The First Morning as a Man, Not a Boy

The Symbolism of Morning

Only the harsh screech of a crow over the moat tears through the silence before dawn. In the cool, misty half-light of the family pavilion, the scent of agarwood incense thickens — a fragrance offered to the gods and used to calm human hearts. On polished hinoki floorboards kneels thirteen-year-old Saburō, the third son of the Akiyama clan’s daimyo. Just moments ago, he was a wakashū – a boy with soft features and a childish nickname. Today, in the fifth year of Ōnin (1473), he awaits his genpuku: the birth of a samurai.

Name and Sword

Name and Sword

His father, Akiyama Motokata, emerges from the shadows. In his hands he holds a rectangular plaque of cypress wood: inscribed with calligraphy in ink. The old childhood name is ceremonially burned in an oil lamp, and the youth hears the new one: Akiyama Katsunori — “He who triumphs through a righteous mind.” The character 勝 (katsu) is taken from the name of the sovereign whom the clan serves; the character 憲 (nori) signifies the kyōgi code passed down through generations. In this act, the boy accepts a double loyalty: to his father-clan and to his oyakata-sama.

A yamabushi warrior-hermit enters the pavilion – he had been chanting prayers since the evening on a nearby mountaintop. Over his black-and-red ō-yoroi armor, he carries a short wakizashi wrapped in bleached paper with a wave motif. The steel was tempered in the icy waters of the Takase River the day after a favorable fire divination. To the sound of shō and hichiriki, the hermit recites words attributed to the warriors of Hachiman – divine soldiers whose sword and soul were one:

“The sword is the mirror of the soul.

If the soul is pure, the blade will remain unstained.”

As Katsunori clasps the sword with both hands, the entire effort of years of training — hands bruised by bokken, evenings spent over calligraphy, kata polished in silence — fuses with the shimmering hamon of the wakizashi blade, becoming a condensed essence of body, mind, and steel.

The First Command

In response, he hears his first command: to set out with the yūshi-tai (勇士隊), a company of young warriors who, under the leadership of a senior ashigaru, guard the mountain pass of Torikabuto. A duty, not a baptism by fire – but a duty that already today separates the child from the man.

The sun climbs over the walls. Crimson rays dance on lacquered armor, incense mingles in the air with the sharp scent of weapon oil. Katsunori leaves the courtyard slowly, as if each memory of play in the garden were being seared away by fire. At the gate, his peers await – those who will undergo their own genpuku a year or two from now. To them, the boy still looks familiar. Only in his eyes, beneath the shadow of the eboshi, gleams something unfamiliar – the sober glint of readiness for death and a life in accord with the sword.

What Is Genpuku?

The Origins of the Rite (Nara and Heian Periods)

Upon the youth’s head was placed a lacquered kanmuri or the more everyday, soft eboshi. This was no ordinary headwear – rather, it was a sign of transformation, a crown of initiation, a clasp that sealed off childhood. With it came a new name, called eboshi-na – often including a character bestowed by the father, master, or sometimes even the emperor. The attire was also changed, abandoning children’s garments for ceremonial kariginu or colorful robes cut in the style of adults. The hairstyle too was altered – hair, previously worn loose, was now tied and styled appropriately for mature men. Thus, the youth shed his former identity: name, body, and form were symbolically cast off, and a new identity was born in the eye of the ritual.

Although in the Heian period this ritual remained the domain of aristocratic families – full of subtlety, poetry, and gestures rooted in ceremonial etiquette – already in its shadow, harsher forms were beginning to take root. The world of warriors, then only beginning to emerge from the mists of the provinces, would soon turn genpuku into a tool for tempering the spirit, and the soft eboshi cap would be replaced by the hard kabuto helmet. But before that happened, Japan – like a youth on the threshold of genpuku – would for a moment longer gaze into the mirror of Chinese heritage, trying to find its own face within it.

The Japan of Samurai (Kamakura–Muromachi Periods)

The aristocratic kanmuri gave way to the military kabuto – a helmet bearing the clan crest. The silk kariginu was replaced with dō-maru armor or at least a ceremonial set of combat equipment. The change was not merely symbolic – it was an open declaration of readiness for battle. From that day forward, the youth became a full member of the samurai hierarchy, directly subordinate to his daimyō or family elder. To be taken under his patronage was not only an honor, but also a commitment: from now on, every command, every campaign, every skirmish – could be the last.

The age at which genpuku was conducted depended on many factors: health, clan status, but above all, political circumstances. In times of peace, genpuku could occur around the age of fifteen. In times of war – even earlier, as long as the boy could wield a weapon. There are known cases of genpuku held at the age of twelve, even eleven, when war knocked at the gates of the family castle. It was also a necessary condition for a samurai to marry, inherit land, or command a unit.

From the Kamakura period onward, the genpuku ritual ceased to be merely an entry into adulthood – it became a sharp edge between life and death, a foreshadowing of all the trials that the way of the sword would bring. The boy was now seen not only as the heir of the clan, but as a future warrior, whose name – given during the ceremony – was to be remembered for eternity… or lost in the chaos of the battlefield.

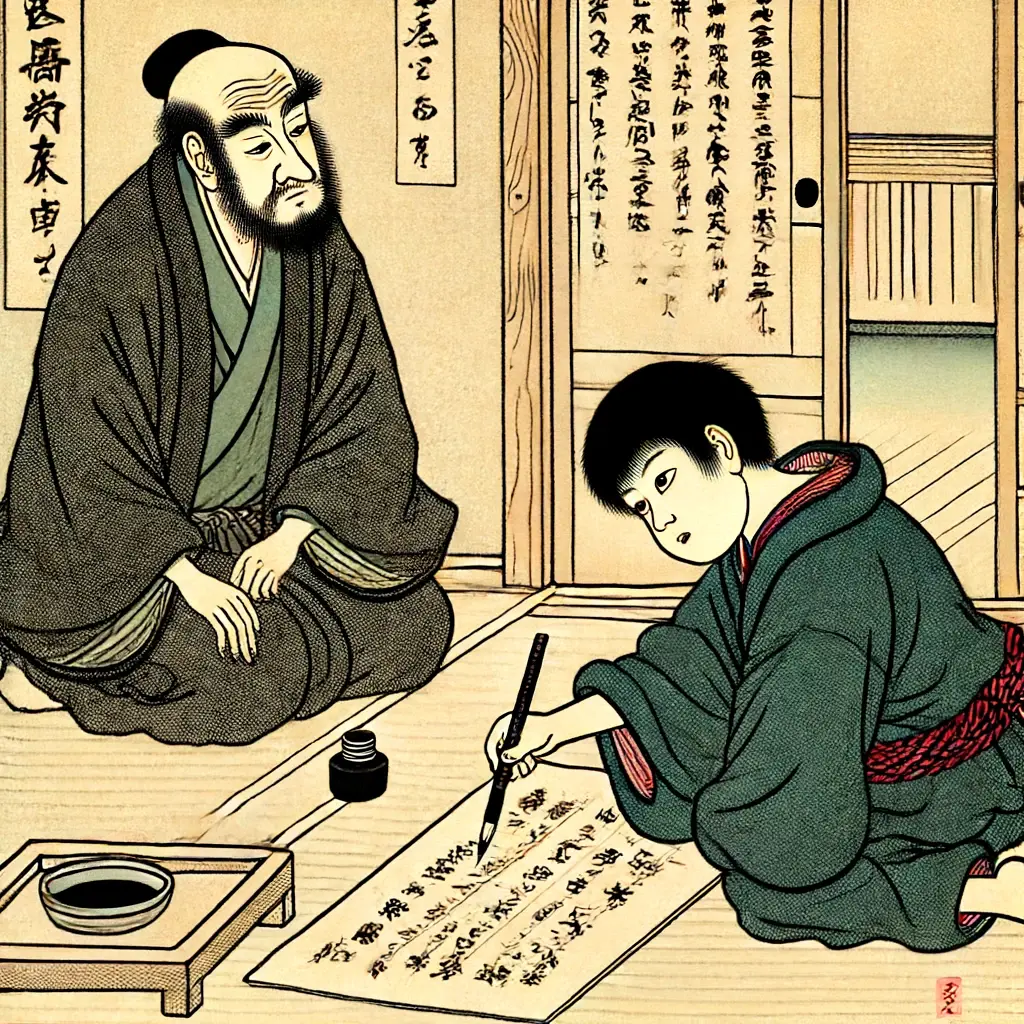

Education of the Young Samurai

From early mornings, before dawn, the boy trained kenjutsu – the art of sword fighting, and jūjutsu – unarmed combat, including throws, joint locks, and grappling in armor. He was also taught kyūjutsu, or archery, as well as horseback riding. Yet a samurai was not merely a killing machine. Equal emphasis was placed on calligraphy (shodō), etiquette (reihō), composing poetry (waka, renga), and the recitation of Confucian and Buddhist classics. It was precisely the beauty of form — of gesture, brushstroke, bodily movement — that was meant to shape inner order, without which a samurai would be no more than a dangerously efficient bandit. The boy learned not only how to wield a sword, but also how not to draw it rashly (more on the teachings of the young samurai here: What skills a Samurai Must Have – Skilled Assassin, Sensitive Poet, Disciplined Philosopher?. And, though at a slightly later stage, here: Yagyū Munenori: The Kenjutsu Master Who Taught the Shōguns That the Most Perfect Strike Is the One You Do Not Deliver ).

With the name came readiness for death — not abstract, but real, inscribed into the ethos of bushidō, which, although not yet codified or named at the time, lived in practice: in the examples of elders, in the stories of ancestors, in the silence of teachers. The boy who accepted the sword also accepted the shadow of his own end — not as a tragedy, but as proof of life’s meaning. For to be a samurai meant to live in such a way that one could die at any moment.

The Course of the Genpuku Ceremony

Choosing the Day and Conducting the Ritual

The date of genpuku was not selected according to participants’ schedules but was determined by the clan’s astrological consultant: a fortunate day was chosen under the sign of kinoto (wood and earth) or within the rokka (divinatory) cycle, so that the deities would consent to “open the gate of adulthood.” In the castle or in a shrine near a monastery, an altar was set up with sakaki branches and bowls of rice. The ceremony was led by the father or head of the clan – the daimyo – accompanied by two assistants: one of the clan officials and a Shintō priest. The father guided the gestures of his son; the priest sprinkled him with salt and sake, reciting norito prayers for strength of spirit. With each step, the youth moved from the half-darkness of the reihō-dō (the purification place) toward the brightly lit main hall – a visual metaphor for the transition out of the shadow of childhood.

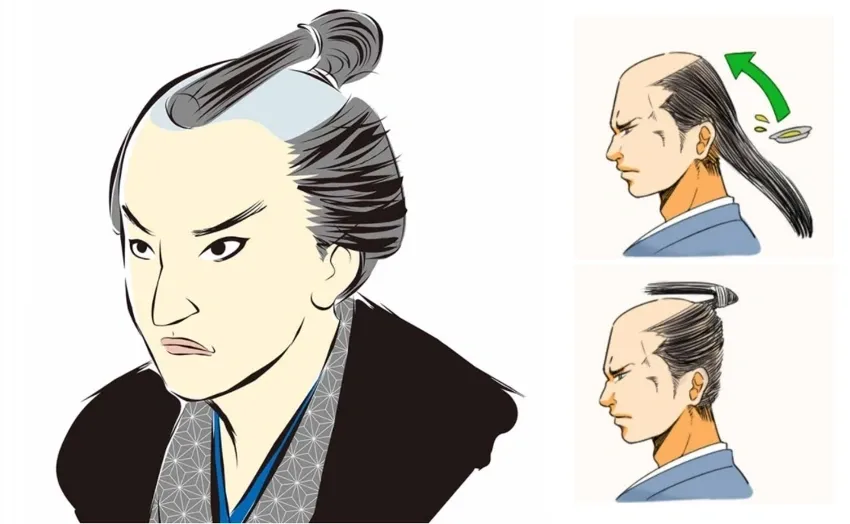

The Razor’s Edge and the Scent of Incense

The Razor’s Edge and the Scent of Incense

First, the master barber (yui-dō) shaved a triangular area of hair at the crown of the head, creating the sakayaki. The hair was cut with a razor moistened with aromatic water infused with iris – a plant believed to “cut off evil currents,” as recorded in Muromachi-period herbals. A lock of the first trimmed hair was placed on a sheet of white washi, sprinkled with sake, and offered to the household altar of the ancestors, so that the “old self” might be accepted into the clan’s afterlife.

The Robes and Arms of Adulthood

The Robes and Arms of Adulthood

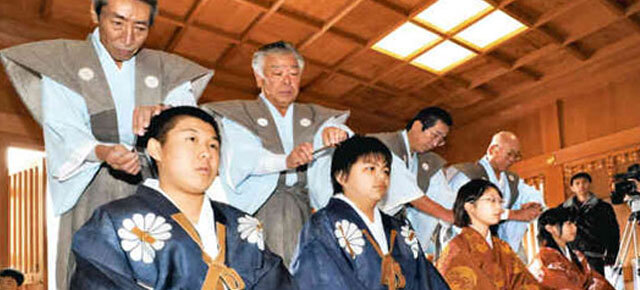

When the head was wrapped in a soft eboshi or, in the martial variant, a light kabuto-bonji (ceremonial helmet), the youth donned an embroidered hitatare bearing clan crests – a jacket of indigo, the color of resilience. Over it was placed a pleated hakama made of hemp (in summer) or ramie (in winter); a sash obi secured the tachi – the first sword – with its blade pointed downward, as dictated by courtly etiquette. The solemn moment of presenting the weapon often included its own prayer: the clan elder would take the blade in hand, lightly strike it against the floor to “awaken the steel,” and only then pass it to the initiate.

A New Name – New Loyalties

Once dressed, the youth knelt on the tatami. The daimyo or father read aloud a scroll bearing the new name – always including one character borrowed from the senior’s name, thus cementing the personal bond of on-giri, the “debt of gratitude.” The name was inscribed in ink on a hinoki cypress tablet and immediately entered into the clan’s registry. Only at this moment did the boy become a legal subject of inheritance; without this act, he could not marry or command a unit.

Public Acknowledgment

The ceremony sometimes lasted barely an hour, but it resulted in a change for life: the boy emerged from the hall already a warrior, bound to serve and, if necessary, to die – with his face turned toward his clan and his sword.

What Happened to Genpuku Later – Edo, Meiji, and Up to the Present?

In this way, the spirit of genpuku has survived – not as an unchanging institution, but as an echo of an ancient ideal: that adulthood is more than age. It is responsibility. It is a name that must be borne.

The Shadow of the Helmet at the Threshold of Adulthood

In an era where the boundaries of adulthood blur under the pressures of education, economics, and modern psychological insight, it is worth asking: do we need a contemporary genpuku? Not as a reenactment, but as an answer to the question: what is maturity? Can it be grasped in a single gesture, a ceremony, a moment?

For genpuku was always more than just a transition into manhood. For yes – the custom unfortunately concerned not only the privileged ruling class – but only one half of it. The other half – women – were not included in genpuku (though they had their own customs, which we shall write about another time). Genpuku was a mirror of society – it showed what was valued: courage, loyalty, virtue, readiness for sacrifice. It shaped not only warriors, but also the very concept of adulthood in Japan. And though Japan today wears different clothes, no longer shaves the sakayaki, and names are now granted by officials, not daimyō – the question of the moment when a child becomes a responsible person remains the same.

Perhaps the spirit of genpuku has survived not in armor or slogans, but in the longing for adulthood to be more than age – to be a merit.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era

10 Facts About Samurai That Are Often Misunderstood: Let's Discover the Real Person Behind the Armor

The Japanese Art of Fragrance in the Warrior Life and Death of the Samurai

A Heart of Iron. The Samurai Dō Breastplates

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Name and Sword

Name and Sword

The Razor’s Edge and the Scent of Incense

The Razor’s Edge and the Scent of Incense The Robes and Arms of Adulthood

The Robes and Arms of Adulthood