A Heart of Iron. The Samurai Dō Breastplates

Armor as protection, identity, an expression of ambition and worldview

胴 (Dō) – The Meaning of the Character and Name

The kanji 胴 consists of two parts: on the left is the radical ⺼, meaning “body,” “flesh”—that which is living, corporeal, organic. On the right is the character 同, meaning “together,” “the same.” The union of these two ideas creates a character that literally refers to the trunk, the torso—the central part of the human body, where the heart beats, the lungs reside, where life force is concentrated.

In this sense, the breastplate was not merely a protective element—it became a kind of second skin. It enveloped not just the body, but the samurai's ki (you can read more about ki here: The Kanji 気 (Ki) – What Can We Learn from the Japanese Concept of Energy in Human Relationships?). With the dō, the warrior did not merely defend life—he declared that his life held value—and that is precisely why samurai breastplates were often beautifully and richly adorned.

The History of Japanese Breastplates (Dō)

Before the samurai breastplate dō took on its characteristic form that so fascinates us today in museum displays, it underwent a long evolution—both as a tool of survival and as a vehicle of aesthetic expression and status. Every era in Japanese history left its mark upon it: from the austere pragmatism of clan wars to the refined ornamentation of peaceful times. To understand the dō, one must delve into the history of Japanese armament—a history shaped not in isolation, but in dialogue with continental influences, local innovations, and—of course—the bloody wars of Japan.

When Iron Came from the Continent

When Mobility Became Key

When Mobility Became Key

A true revolution came with the Kamakura period (1185–1333), when war began to resemble constant skirmishes more than ceremonial clashes of mounted archers. Warriors needed armor that allowed movement, climbing, and close combat. It was then that more flexible constructions emerged—such as dō-maru and haramaki-dō—which enveloped the torso not like a box, but like a tightly fitting breastplate that opened from the side or back. The first constructions with hinges appeared, and the dō began to acquire an individual character—as a separate piece of armor, often determining its overall style.

When War Became Industry

Each clan developed its own solutions, and some dō types gained fame: yukinoshita-dō of Date Masamune, mōgami-dō from Akita, or the grotesquely expressive niō-dō, pressed into the shape of emaciated monks. Armor became a signature, and the dō—the heart of its form.

From Battlefield to Ceremonial Hall

Wearing armor in the Edo period was more a ritual than a preparation for battle. The dō then became a testament to status, ancestral heritage, and aesthetic taste. Yet it remained the central element of the armor—the focal point of the gaze, the weight, and the meaning of the entire suit. And though it no longer stopped arrows and blades, it did not cease to protect—now safeguarding dignity, memory, and samurai identity.

Types of Dō Breastplates

Below we will explore two main classifications of the dō: the first concerns construction—that is, the architecture of the breastplate and how it is worn; the second concerns style, encompassing techniques, outward form, and aesthetic characteristics.

Construction Types – How the Dō Opens to the World

□ Go-mai dō (五枚胴) – "five-plate breastplate," a more flexible variant composed of five smaller elements: two front, two side, and one back plate. With more connection points and a greater number of "folds," it better conformed to the warrior's body and allowed for greater range of motion. Ideal for infantry and mounted officers who needed a balance between protection and mobility.

□ Ryō-awase dō (両合わせ胴) – armor that opens on both sides, symmetrical. The front and back are identical, and the fastenings are located on both sides. This type had a great advantage: it could be quickly removed if the samurai was wounded or if there was a need to rapidly change attire. This construction was rarer, but valued for its practicality.

□ Maekake dō (前掛け胴), also known as haraate (腹当て) – the simplest of all, limited to the front plate only. It did not protect the back, so it was used rather as an additional reinforcement, for example under a kimono or during training. Occasionally it was also used by ashigaru—foot soldiers—when entire units had to be outfitted quickly and cheaply.

Stylistic Types – When the Dō Speaks of Aesthetics and Region

□ Dō-maru (胴丸) – opens under the right arm, often without hinges, tightly wrapping the body. This was a type of elite armor, worn by higher-ranking samurai in the Kamakura and Muromachi periods. Its construction resembles that of an ancient knight’s armor, but with the full finesse of Japanese lacing and lacquering.

□ Hotoke dō (仏胴) – with a smooth, polished surface, almost without divisions or bulges—resembling the calm belly of a meditating Buddha, hence the name. It was an aesthetic choice—a symbol of simplicity, calm, and inner strength. Often lacquered in deep black or red, sometimes with subtle golden ornaments.

□ Yukinoshita dō / Sendai dō – associated with the legendary Date Masamune, the famous one-eyed daimyō of Sendai. Characteristic of the Tōhoku region—it combined a striking appearance with simplicity of construction. Often included unique details, such as lacquered plates in a plum hue and original proportions.

□ Mōgami dō (最上胴) – an “overlapping” type of armor, with horizontal segments slightly overlapping each other. Valued for its flexibility and impact resistance.

□ Hatomune dō (鳩胸胴) – with a central protrusion resembling a pigeon’s breast—a borrowing from European peascod-style breastplates. Often used in contact with the Portuguese and Spanish in the 16th century—a sign of nanban influence ("southern barbarians"—i.e., Europeans, primarily Portuguese and Spanish).

□ Dangae dō (段替胴) – “layered armor,” often combining various techniques and styles in a single construction—for example, the lower part riveted, the upper laced, sometimes multicolored. A favorite type among eccentric daimyō.

In this way, the dō—the samurai breastplate—ceases to be merely a piece of metal upon a warrior’s chest. It becomes a story of region, era, status, character, and imagination of its owner. And each of its variations is like a verse—a fragment of the great saga of the Japanese spirit of war, inscribed in lacquer, metal, and silk.

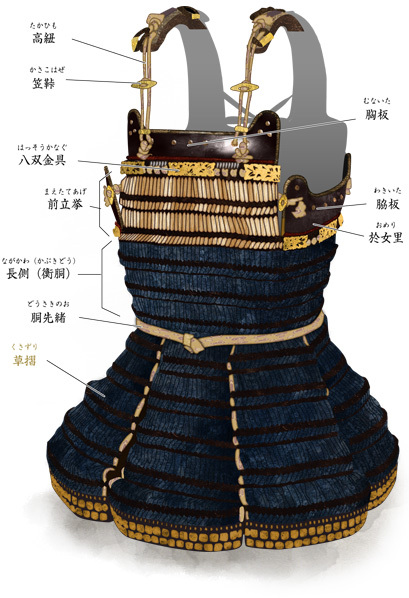

How the Samurai Breastplate (dō) Is Constructed

Although samurai armor may appear from a distance as a uniform shell, every part of it is the result of precise engineering, artisanal craftsmanship, and aesthetic imagination. Especially the dō—the breastplate—is not merely “metal on the chest,” but a complex structure in which every component serves a specific purpose: protective, structural, decorative, or symbolic. Its anatomy resembles that of a body—it has, in a sense, a spine, shoulders, muscles, and skin. Let us now take a closer look at this armored physiology.

The Heart of the Breastplate

The Heart of the Breastplate

The most important element of the dō is the set of main plates that form its core—protecting the chest and back. At the front is the nagagawa (長側)—a large, often arch-shaped front plate. At its top may sit the tateage (立挙)—an additional segment raised and tied to the shoulder guards, which protects the upper chest and sternum while also allowing for better adaptation of the breastplate to the posture of the body.

Depending on the period and style, these plates could be smooth (as in hotoke-dō), vertically or horizontally riveted (as in okegawa-dō), composed of segments (go-mai), or made from small interlinked plates (tatami-dō). The thickness of the steel ranged from a few to over ten millimeters—thick enough to stop a sword cut, yet not so heavy as to hinder movement.

Kanagu mawari – Ornamental Frame and Fastening System

→ Munaita (胸板) – the upper plate beneath the neck, protecting the throat and upper chest. Often protrudes slightly forward, sometimes covered with leather or lacquered.

→ Oshitsuke-no-ita (押付板) – panels pressing the upper part of the armor against the body, often with a chin cut-out.

→ Wakiita (脇板) – small side plates beneath the armpits—hidden, but essential for wearing comfort.

→ Watagami (綿上) – the shoulder straps of the armor, broad and flexible, often covered with leather and silk, connecting the breastplate with the helmet or sleeves (sode). Their shape spoke volumes about the owner's class and taste.

Some of these parts were additionally adorned with gold, engraving, embossing, or family crests.

Kusazuri – The Protective Apron

The number of segments varied depending on the type of armor—most often four to seven—and their arrangement could be asymmetrical, especially in haramaki-dō. Over time, they were also decorated, for example by using cords in the clan’s colors (odoshi), painting symbols on them, or adding ornamental studs.

Other Details: Gyōyō, Kohire, Kattari, Uketsubo, Fukurin

▫ Kohire (小札) – small “sleeves” or shoulder guards made of plates, protecting the upper arm.

▫ Kattari (割立) – reinforcements and protrusions that stabilized the dō and helped keep it in proper alignment on the body.

▫ Uketsubo (受壷) – metal rings used to fasten belts, harnesses, or additional weaponry.

▫ Fukurin (縁金) – metal edging of the plates, often made of brass or gold-plated steel. Not only did this reinforce the structure, but it also gave the armor an elegant, refined appearance.

Ornamentation – The Armor as a Canvas

- Mon (紋) – family crests—often painted or embossed on the front or back of the breastplate. Simple, symbolic, elegant (more about samurai family crests can be read here: Kamon of 15 Strongest Samurai Clans of Japan).

- Lacquer (urushi) – resistant to moisture and corrosion, used in black, red, indigo, and even gold finishes.

- Odoshi (縅) – the lacing of the armor, which not only joined the segments but also gave it a distinctive color identity. The colors of the odoshi could indicate clan, rank, personal taste, or affiliation with a school of combat.

Each dō was therefore not only a mechanism of protection but also a manifesto of identity. Its parts—like organs in a body—worked together, creating harmony between movement, defense, art, and the warrior’s spirit.

How the Dō Was Worn and Fastened

Samurai armor was not hastily thrown on like a coat—putting it on was a ritual. The dō was donned slowly, with precision, often with the help of a servant or fellow warrior who knew where to pull and where to loosen in order to secure it firmly without shifting the center of gravity.

Movable segments such as the tateage or detachable kusazuri were often secured with kohaze—metal hooks or clasps that on one hand facilitated putting the armor on, and on the other allowed for quick adaptation to the situation: marching, infantry combat, or mounted warfare. Watagami and sode (shoulder guards) also had separate fastenings—designed so their weight was evenly distributed and did not restrict arm movement during swordplay.

Removable kusazuri or maekake dō–type armor, which protected only the front of the body, were favored by those who prioritized speed, comfort, or simply—style. Because in the world of the samurai, every detail mattered—not only how you fought, but how you presented yourself as you stood motionless beneath the sky, waiting for the first sound of the battle drum.

What Were Samurai Breastplates Made Of?

In ceremonial armor, the craftsman's artistic expression came to full bloom. Engravings, embossing, gilding, and intricate paintings depicting dragons, lions, lotus flowers, or Buddhist inscriptions appeared. Some armors even featured embroidered silk linings with quotes from Zen texts or family mottos. Every detail—from the arrangement of rivets to the color of the lacing—was intentional. The dō did not only protect—it spoke of spirit, lineage, and history.

Practical Features and Functionality of the Dō

A samurai had to fight regardless of the season—in summer heat and humidity, in winter snow. Thus, the dō had to be as “breathable” as possible. In segmented constructions, the spaces between plates naturally served this function, and the lacing allowed for tension adjustment. There were even armors that adapted to changes in body weight—thanks to flexible joints, cords, and open-back construction, the dō could “grow” with the warrior. This was particularly important in the Sengoku era, when soldiers fought in multi-week campaigns, often gaining or losing weight week by week.

Not every dō was made for the same purpose—ceremonial versions emphasized aesthetics, while combat versions prioritized durability. Removable kusazuri allowed the warrior to march long distances without hip pain, and then prepare for battle within minutes. Practicality was built into the structure of the dō—not as a compromise, but as a fundamental value. Armor was not an obstacle but an ally. And just as the sword had to become an extension of the arm, so the breastplate became an extension of the spine, a shield for the heart, a frame for courage.

The Multifaceted Role of the Dō

It is enough to compare the yukinoshita dō on one hand, and the lavish armor of a daimyō from Kyoto on the other—the former almost ascetic, the latter dripping with purple and gold. Both authentic, both samurai—yet each represents a different philosophy: silent authority versus visual might. This is not merely an aesthetic contrast, but a divergence in views on life, power, and the meaning of combat.

Because Japanese armor—and the dō above all—is not just functional protection. It is a work of craftsmanship, a record of family history, an expression of its owner’s spirituality. In its form it unites logic and beauty, violence and elegance, martial practice and contemplation of life. That is why even today, when we gaze at a dō behind a museum pane, we feel it is more than armor—it is a portrait of the man who wore it.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Men Yoroi: Wrathful and Impenetrable Battle Masks of the Samurai

Wakizashi – The Smaller Cousin of the Katana That Bore the Full Weight of Samurai Honor

Discover the Katana – The Birth, Maturity, Wartime Life, and Noble Old Age of the Samurai Sword

Samurai War Banners: Japanese Heraldry Under Which Battles Were Fought

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

When Mobility Became Key

When Mobility Became Key

The Heart of the Breastplate

The Heart of the Breastplate