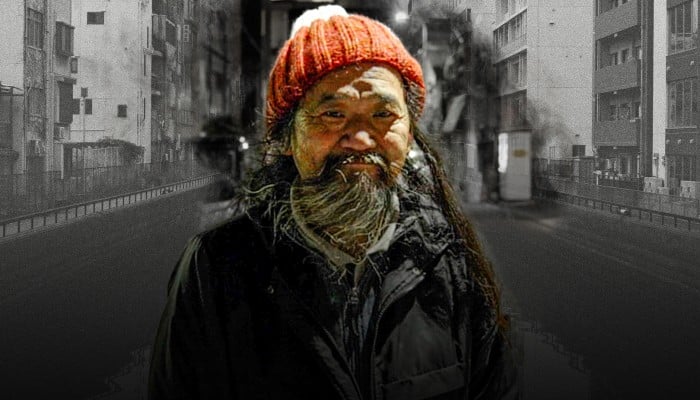

Johatsu – on average, every year over 80,000 Japanese people disappear. They call it 'evaporating.'

What is Johatsu?

The term "johatsu" refers to individuals who, for various reasons – from personal failures, through debts, to excessive social pressure – decide to take the dramatic step of disappearing. This means not just physically distancing themselves from their previous lives but also completely severing ties with their past, family, and acquaintances. This phenomenon, which seems to be both an act of desperation and a search for freedom, shines a light on the darker aspects of Japanese society, where harmony and uniformity are valued above individual happiness.

What is the Concept of Johatsu and Where Does it Come From?

The concept of johatsu is not new in Japanese culture and history. Its roots can be found in feudal Japan, where disappearing could be a choice for those wishing to escape debts, failures, or punishments. However, the term gained widespread use in the 1960s and 70s, when Japan was experiencing rapid economic and social changes. Economic growth and urbanization led many people to move to cities in search of work and a better life, sometimes ending in failure. In such circumstances, johatsu became a way to escape from unsuccessful urban life and return to anonymity.

Today, with the development of social media and digital communication technologies, disappearing has become more difficult but paradoxically also easier to organize thanks to available resources and services that assist in "evaporation." Nonetheless, johatsu continues to reflect the deep social and cultural dilemmas of contemporary Japan, balancing on the edge between traditional values and modern life challenges in one of the world's most developed societies.

The Scale of the Phenomenon of People Evaporating in Japan?

In the 1990s, during and after the economic bubble burst, Japan saw an increase in the number of johatsu, partly related to rapid economic and social changes.

With the arrival of the 21st century and changes in the Japanese economy, the number of reported johatsu cases began to change. The development of technology and social media made it harder to disappear without a trace on one hand, but on the other hand, new methods and services facilitating "evaporation" appeared. Despite this, thousands of new johatsu cases are still reported each year, highlighting the persistence of this phenomenon in Japanese society.

Statistics on johatsu in Japan also show that the phenomenon affects people of various ages, though it is most often middle-aged men. Disappearances are often linked to financial problems, family issues, work-related stress, but also the desire to escape social norms and expectations. Despite difficulties in tracking and precisely quantifying all johatsu cases, these data shed light on the deep social and cultural challenges faced by contemporary Japan.

The Market Does not Like Empty Spaces – The Emergence of Companies Specializing in Organizing "Evaporation"

In Japan, there is a niche of services specializing in facilitating the process of johatsu, or "evaporating" individuals from their current lives. These companies, known as "night moving services" or "yonige-ya" (夜逃げ屋 - night escape shops), offer comprehensive solutions for those wishing to start anew, avoiding confrontation with problems or debts.

How to Find Such a Company?

How to Find Such a Company?

These companies often advertise on the internet, through anonymous forums or specialized websites (sites are easy to search for, also on Google), but also by word of mouth in relevant circles. They operate in a morally and legally gray area, so information about them may be harder to access in traditional media.

How Many Such Companies Are There?

The exact number of companies operating in the johatsu facilitation industry is difficult to precisely determine, mainly due to their often informal nature and tendency to keep their operations secret. Unofficial estimates suggest that several dozen such companies may operate across Japan. However, the market value of these specialized services remains unclear, though it certainly generates significant turnover, considering the high costs associated with organizing "evaporation." The complexity of services, including counseling, planning, moving, and potentially creating a new identity, makes it a high-value niche for those who operate in it. Despite the lack of official data, this industry reflects a significant social need and offers unique services for individuals seeking drastic changes in their lives.

What and How Much Do These Companies Organize?

What and How Much Do These Companies Organize?

These companies offer a wide range of services, from advising and planning the "disappearance" to physical assistance in moving (often at night, to avoid detection) to help in establishing a new identity. The costs of these services vary and can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, depending on the complexity of the task and the distance of the move, as well as what the person wants to escape from and how intense the search might be expected.

How Long Does Preparation for "Evaporation" Take?

How Long Does Preparation for "Evaporation" Take?

The time required to prepare for johatsu depends on individual circumstances and can range from a few days to several months. This process requires careful planning to avoid leaving traces that could facilitate being found by families, creditors, or employers.

These companies operate in a morally and legally gray area, offering people in desperation the possibility to escape their problems. At the same time, their existence underscores a social need, namely dealing with the pressure of life in a highly competitive society like Japan's. Despite the controversies they raise, for some, they represent the last resort. And while one may criticize, in doing so, one must not forget that for many people, this is a choice: johatsu or suicide?

Psychological and Social Aspects of Johatsu The causes of the phenomenon of johatsu, understood as the conscious disappearance from one's previous social life, are diverse, and the impact on the families and acquaintances of the disappearing individuals is often far-reaching and difficult to predict.

Causes of Johatsu

Though there may be as many reasons as there are people, among the main reasons for the decision to disappear, one can distinguish:

-

Social pressure and expectations of success In a culture that highly values academic and professional achievements, failure can be perceived as a great shame. Individuals who do not meet these expectations may feel alienated and compelled to flee.

-

Financial problems Debts and financial difficulties are one of the most common reasons for johatsu. Escape seems to be the only option for individuals who cannot cope with the pressure from creditors.

-

Family conflicts Failed marriages, difficult relationships with parents or other family members can lead to a sense of entrapment and desperation, prompting some to abandon their current lives.

-

Personal crises Depression, a lack of belonging, or identity crises can prompt individuals to seek a new beginning through johatsu.

The Impact of Johatsu on Families and Acquaintances

The consequences of johatsu for the family and acquaintances are usually painful and difficult. Families may feel betrayed, worried, and full of unanswered questions. The grieving and acceptance process of such sudden and inexplicable disappearance is often complicated and lengthy.

-

Lack of closure The lack of information about the fate of a loved one makes the grieving process difficult, leaving the family in a state of uncertainty and continuous waiting for any news.

-

Social stigma and isolation Families of individuals who have undertaken johatsu may experience stigmatization and isolation from the community. In a culture that emphasizes honor and social responsibility, disappearance may be seen as an evasion of these values.

Johatsu has a profound impact not only on the person who decided to disappear but also on wider social and familial circles. Understanding the psychological and social aspects of this phenomenon is key to offering support and assistance both to individuals struggling with thoughts of johatsu and their families.

Examples of Authentic Stories of People Who "Disappeared"

Takuya – Escape from Insolvency

Takuya – Escape from Insolvency

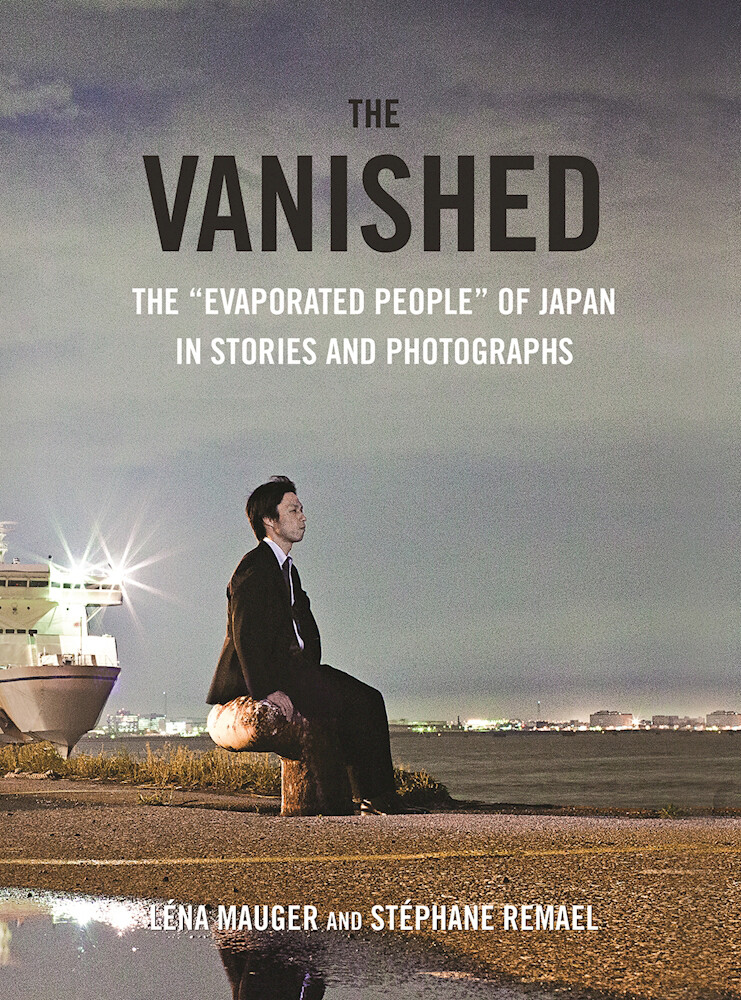

In the book "The Vanished" by Léna Mauger and Stéphane Remael, the story of a man named Takuya is presented, who disappeared to escape mountains of debt. For years, he tried to maintain a facade of success while struggling with growing financial obligations. His decision to undertake johatsu was a final attempt to regain control over his life. Takuya left his apartment in Tokyo in the middle of the night, abandoning his cell phone, credit card, and any documents with his address. Living on the margins of society, he tried to start anew but struggled with feelings of guilt towards the family he left behind.

Escape from Social and Professional Pressure

Another account describes a woman named Yumi, who disappeared to escape extreme pressure at work and family expectations. As a senior corporate employee, Yumi felt overwhelmed by the constant pressure to achieve and not meeting the expectations of a woman in Japanese society. Her decision to undertake johatsu was a desperate step in search of peace and autonomy. Yumi left her previous life without a word, traveling to a remote village where she could live anonymously, working in a local cafe. This change, however, did not bring complete solace, as she struggled with longing for her family and former life.

Escape from a Failed Marriage

The third story concerns Hiro, who decided to undertake johatsu after years of a failed marriage. Domestic conflicts and the impossibility of divorce due to social consequences prompted Hiro to make the radical decision to disappear. He left his life in Osaka and moved to a small town in Hokkaido, where he started anew under a changed surname. Hiro took up work in agriculture, and although he enjoyed a simpler life, he still struggled with feelings of isolation and guilt for abandoning his family.

Support and Assistance for Those Wanting to "Return"

One such initiative is the Tokyo Outreach Program, launched in 2018, which offers counseling and support for people struggling with social isolation or thoughts of johatsu. Implemented by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government in collaboration with non-governmental organizations, the program provides anonymous consultations, psychological support, and assistance with social reintegration.

The NPO Moyai Support Center for Independent Living is another organization playing a key role in assisting people in crisis. Founded by Akira Kitada, this center offers comprehensive support services, including help finding housing, employment, and financial counseling. Moyai focuses particularly on young people who have lost family support and have nowhere to turn.

At the governmental level, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare launched a campaign in 2020 aimed at raising awareness about mental and social issues that can lead to johatsu. This campaign includes funding for local support programs and the development of a support network for individuals at risk of social exclusion.

Success stories of individuals who have benefited from these programs and managed to "return" serve as important testimony to the effectiveness of these initiatives. These and other initiatives highlight the growing awareness of the johatsu issue in Japan and the pursuit of creating a society where everyone can find support in difficult times. The challenges faced by returning individuals are significant, but with available resources and support, many of them can start a new chapter in their lives.

Conclusion

In summary, johatsu is not just a Japanese curiosity; it is a phenomenon that prompts deeper reflection on the values that guide our lives and the social consequences that our choice of life path entails. The stories of those who have decided on johatsu are a reminder of the ongoing struggle between the search for one's identity and the attempt to meet social expectations. As the world becomes increasingly interconnected and social pressures evolve, the phenomenon of johatsu and its interpretations can provide valuable insights into understanding contemporary individual and collective challenges.

>>SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Beyond Stereotypes: The True Face of Hikikomori in Japan and Worldwide

Parasite Singles: Japan's Demographic Dilemma at the Heart of Family

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

How to Find Such a Company?

How to Find Such a Company?  What and How Much Do These Companies Organize?

What and How Much Do These Companies Organize?  How Long Does Preparation for "Evaporation" Take?

How Long Does Preparation for "Evaporation" Take?

Takuya – Escape from Insolvency

Takuya – Escape from Insolvency