Japanese Philosophy of Mono no Aware: The Practice of Mindful Being

What does it mean to feel the transience?

Japan, a country embodying harmony between the past and modernity, is also the guardian of one of the most moving and poetic philosophies of life - Mono no Aware. This expression, which translates literally as "the sadness of things" or "sensitivity to ephemerality," captures the essence of the Japanese soul, prompting reflection on the fleetingness of moments and the inevitability of change. Mono no Aware is a bittersweet feeling, filled with both sadness and deep awe of the beauty of passing moments. In traditional haiku, mystical zen gardens, or in the delicate falling of cherry blossoms (sakura), this sentiment is tangible, permeating everyday life and the culture of the Land of the Rising Sun.

Let's embark on a journey through the various manifestations of Mono no Aware, starting from its roots in ancient literature to contemporary reflections in popular culture, such as anime and video games. Let's try to understand the meaning of this philosophy, to comprehend a bit better the Japanese way of thinking, and perhaps to consider how to incorporate its principles into our own lives. To appreciate each moment more deeply and to experience both beauty and transience more consciously in our everyday existence.

Understanding What Mono no Aware Is

Understanding What Mono no Aware Is

Etymology and Meaning of the Term

Mono no Aware is a term whose roots reach deeply into the history and culture of Japan. It consists of three parts: "mono" (物), which means "things" or "objects"; "no," a connecting particle used to form compound phrases; and "aware" (あわれ), which is an archaic expression of emotional response to the perception of beauty and ephemerality. Aware originates from a sensitivity to the inevitable passing, being a source of both beauty and sorrow. In classic Japanese literature, this concept was often used to describe feelings evoked by the subtle beauty of nature, which is transient and prompts reflection on the ephemerality of life.

Historical Roots of Mono no Aware

The classical literature of Japan is replete with descriptions and references to Mono no Aware, as evidenced in "The Tale of Genji" (源氏物語, Genji Monogatari), considered the world's first psychological novel. Murasaki Shikibu, the author, weaves a narrative around subtle emotions and the ephemeral beauty that fades just like cherry blossoms. It is this epic tale that most fully conveys the essence of Mono no Aware, depicting life as a series of moments filled with beauty and nostalgia.

Mono no Aware in Everyday Life

Amidst the hustle and bustle of daily life, the concept of Mono no Aware is like a subtle breeze reminding us of the transience of moments. The Japanese find this deep sentiment in the cyclicality of nature - in the blooming cherry blossoms whose short-lived beauty gathers crowds each year, or in the quiet falling of momiji leaves, symbolizing the change of seasons. These natural phenomena serve as reminders that every moment is unique and irreplaceable, encouraging deep reflection.

Practicing Mono no Aware in personal life begins with an awareness of transience. It's about embracing and becoming acquainted with the inevitability of changes that come with time. It's not about a melancholic focus on the end, but about realizing that it is transience that adds value to our experiences. This awareness brings deeper gratitude for the present moments and allows a better understanding of our place in the ever-changing world.

The Significance of Mono no Aware in Art, Philosophy, and Culture

The Significance of Mono no Aware in Art, Philosophy, and Culture

Mono no Aware has influenced Japanese art and culture, becoming almost the quintessence of Japanese aesthetics. In the poetry of haiku, which is the essence of Japanese literature, moments of Mono no Aware are often found, where capturing a fleeting moment of nature is reflected in the emotional depth and ambiguity of words. In the visual arts, such as painting and ikebana, this aesthetic is reflected in the delicacy of forms and thoughtful composition. In philosophy, Mono no Aware connects with Buddhism and Shintō, emphasizing the naturalness of transience and its beauty. It is not about succumbing to pessimism, but rather a celebration of life with full awareness of its transiency. This way of viewing reality teaches us that the true depth of experiences lies not only in joy and success but also in accepting sadness and loss as integral parts of existence.

Mono no Aware and minimalism

Mono no Aware and minimalism

Mono no Aware and minimalism may at first glance seem like distant concepts, yet in reality, they are closely intertwined. Both draw from a profound appreciation for the essence of things and the pursuit of harmony. In Japanese design and lifestyle, minimalism often manifests as a respect for simplicity, which is reflected in the aesthetics of Mono no Aware, where the modesty and transience of moments are valued.

Embracing a minimalist approach in everyday life can serve as a tool to better appreciate passing moments. By reducing possessions and commitments, minimalism fosters a more attentive and focused existence, where each thing and each action are more deliberately considered and experienced, enabling a deeper engagement with Mono no Aware.

Significance of Mono no Aware for mental health and well-being

In the aspect of mental health, Mono no Aware can lead to greater emotional awareness. By recognizing the fleeting nature and inevitable changes in our emotions, we learn to accept our feelings as they are, without the compulsion to change them. This acceptance is crucial for mental health as it allows emotions to flow naturally, without excessive repression or amplification. Accepting that our emotions are temporary and changing, just like everything in nature, can help us better deal with difficult feelings and enjoy positive moments, without clinging too tightly to them. Mono no Aware teaches us that every emotion brings opportunities for growth and personal transformation.

Mono no Aware also encourages the practice of mindfulness and presence in the moment, which is a vital aspect of mental health care. By mindfully living in the "here and now" and appreciating each moment, whether pleasant or challenging, we learn to cope with change and loss, and our life experiences become richer and more complete. Mono no Aware offers a perspective that facilitates navigating through these difficult processes. By embracing the philosophy of Mono no Aware, we begin to understand and accept impermanence as a natural part of life, which can help alleviate pain and provide a sense of continuity even in the face of personal losses.

Mono no Aware in Anime

The role of Mono no Aware in anime is pivotal for understanding many Japanese productions, which often focus on the ephemeral moments of human life, accentuating the beauty and sadness of passing. Anime creators use this philosophy to give depth to their stories, create complex characters, and build an atmosphere that resonates with the audience's emotions. The visual aspect of anime allows for a unique presentation of ephemeral moments, such as falling cherry blossom petals, which are a common symbol of Mono no Aware.

"5 Centimeters Per Second" (Byōsoku Go Senchimētoru)

In the anime "5 Centimeters Per Second," director Makoto Shinkai explores the concept of Mono no Aware by depicting the story of two people who gradually drift apart both literally and metaphorically. The message of impermanence and interpersonal distance is emphasized by the beauty of passing landscapes and fleeting moments, which are central to the narrative.

"Your Name" (Kimi no Na wa)

"Your Name" (Kimi no Na wa)

Another work by Shinkai is "Your Name," where the theme of Mono no Aware is underscored by the body exchange between the main characters, allowing them to cherish the fragile moments of community and understanding before being separated again. This intertwining of personal experiences with a larger, cosmic balance embodies Mono no Aware, pointing to the transience of human experiences.

"Anohana: The Flower We Saw That Day" (Ano Hi Mita Hana no Namae o Bokutachi wa Mada Shiranai)

"Anohana" is a series that focuses on a group of friends who must confront trauma and the transient nature of life following the loss of one of their own. In this story, the memories and emotions brought about by the deceased character, Menma, are infused with Mono no Aware as the characters learn to accept the fleeting nature of life and the significance of the moments they shared.

"Clannad"

"Clannad"

In "Clannad," we witness a complex narrative about family, friendship, and loss. Many scenes in the anime, including those depicting the changing seasons, the passage of the characters' youth, and their confrontation with the hardships of adulthood, reflect the spirit of Mono no Aware, where every moment is precious, but inevitably fleeting.

"The Tale of the Princess Kaguya" (Kaguya-hime no Monogatari)

This Studio Ghibli anime is an adaptation of a Japanese folk tale and is rife with images embodying Mono no Aware. The story of Princess Kaguya's life, from her mystical birth to her inevitable departure, represents the life cycle and its transience, as well as a profound reflection on what truly matters in life.

Dragon Ball: Farewell to Krillin

Dragon Ball: Farewell to Krillin

In the "Dragon Ball" series, though action and battles dominate, the philosophy of Mono no Aware appears in quiet, moving moments. An example is when Goku discovers that his friend, Krillin, has been killed by Tambourine. It's a moment when Goku experiences a powerful sense of life's fragility and intense emotions associated with loss. Although the series is full of character revivals and returns from death, this moment emphasizes that every moment spent with loved ones is precious and unique.

Naruto: Farewell to Jiraiya

In "Naruto," the death of Jiraiya is one of the most poignant moments and an example of Mono no Aware. His death impacts not only the titular character but also leaves the audience with reflections on the transience of life and the influence one person can have on the lives of others. It introduces a tone of contemplation into the dynamic series, reminding us that even in a world full of battles and adventures, there are moments of silence and reflection.

Mushishi

Mushishi

"Mushishi" is a series that wholly bases itself on concepts such as Mono no Aware. Each episode unveils a new "Mushi" and tells of human interactions with these mysterious beings, often exploring themes of impermanence and the ephemeral beauty of the world.

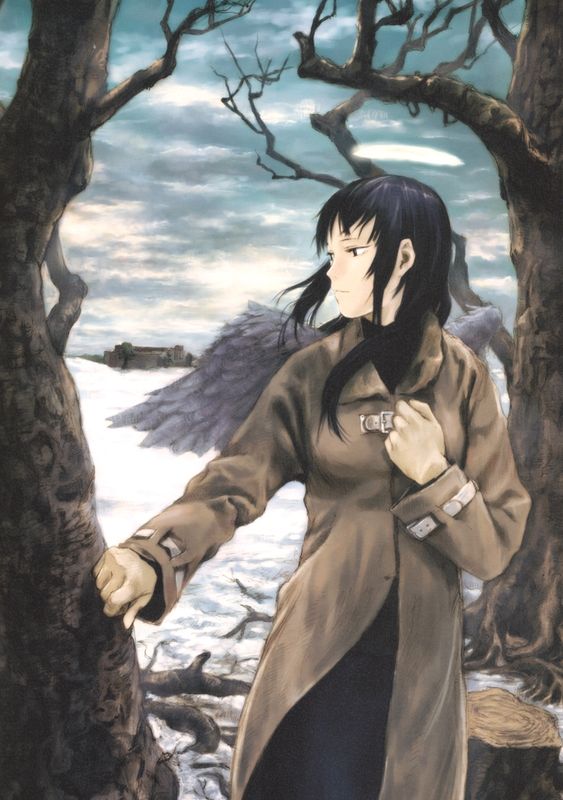

Haibane Renmei

"Haibane Renmei" is a subtle and emotionally resonant tale that reveals the life of a group of haibane—angel-like beings. The series gently touches on themes of loss, the passing of time, and the search for meaning in life, all tightly linked with Mono no Aware. Viewers witness the characters' development, their internal struggles, and spiritual growth, which are closely related to musings on the fleeting nature of existence.

Mono no Aware in Contemporary Japanese Culture

In the realm of literature, mono no aware often lurks between the lines. For instance, Haruki Murakami, one of the most renowned contemporary Japanese writers, in his novel "Norwegian Wood," depicts fleeting moments of youth and first love, painting scenes filled with nostalgia and yearning for what will not return. Another of Murakami's novels, "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle," is also imbued with the feeling of mono no aware, where disappearing characters and shape-shifting realities mirror the transitory nature of existence.

In the field of architecture and design, the influence of mono no aware is visible in trends such as Japanese minimalism. For example, Muji's renowned designer Kenya Hara, in his book "Designing Design," emphasizes the importance of "emptiness" and "invisibility" in design, echoing the mono no aware philosophy – appreciating subtlety and fleeting beauty in the simplicity of everyday objects.

In filmmaking, mono no aware is reflected in the delicate, contemplative films like Hirokazu Kore-eda's "Our Little Sister." This film, full of sorrow but also beauty, tells the story of four sisters after their mother's death, exploring the deep melancholy and delicacy of human relationships.

In summary, although contemporary thinkers and artists may seldom use the term mono no aware, its essence still manifests across diverse facets of Japanese culture. Through specific literary works, art, design, and cinema, mono no aware remains elusive yet persistently present, showcasing the beauty and sadness of transience in everyday life.

Living in the Here and Now

Mono no aware is not just an aesthetic pillar or a literary motif; it's an opportunity to experience the depth of life daily. By paying attention to transience, the Japanese have for centuries found beauty in the ephemeral – from seasonal changes in nature to fleeting moments of human existence.

In practice, Mono no Aware manifests in the celebration of moments that evoke reflection and emotional response. This is visible in native festivals, traditional ceremonies, and even in modern design, where simplicity and functionality are paired with appreciating the present moment. It is a philosophy that quiets the noise of the everyday, allowing one to notice and cherish what is too often overlooked. It could be a passing smile, the tranquility of the morning air, or the nostalgic tone of an old song. Mono no Aware teaches that each of these moments is a precious element of our experience, deserving of our attention.

Thus, while Mono no Aware may seem like a concept rooted in the past, its influence lives on – adapting and evolving with Japan's dynamic culture. By embracing this perspective, we can not only connect more deeply with the Japanese way of life but also uncover universal values that transcend boundaries and time. Mono no Aware is a reminder to live in the here and now, appreciating the beauty of transience that surrounds us every day.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Understanding What Mono no Aware Is

Understanding What Mono no Aware Is The Significance of Mono no Aware in Art, Philosophy, and Culture

The Significance of Mono no Aware in Art, Philosophy, and Culture Mono no Aware and minimalism

Mono no Aware and minimalism  "Your Name" (Kimi no Na wa)

"Your Name" (Kimi no Na wa)  "Clannad"

"Clannad"  Dragon Ball: Farewell to Krillin

Dragon Ball: Farewell to Krillin  Mushishi

Mushishi