Beyond Stereotypes: The True Face of Hikikomori in Japan and Worldwide

The Phenomenon of Lonely Souls: What is hikikomori?

However, hikikomori is not a phenomenon limited only to Japan. Similar cases are appearing in various corners of the world, forcing us to reflect on the global dimension of this issue. The increasing numbers of people withdrawing from social life in countries outside of Japan indicate that the hikikomori phenomenon is much more complex and universal than it might seem at first glance.

Definition and Scope of the Problem

Hikikomori is a term originating from the Japanese language, which in the simplest translation means "isolating oneself". However, in a socio-cultural context, this term has taken on a much deeper meaning. According to the official definition of the Japanese government, hikikomori are people who remain isolated in their homes for at least six consecutive months and rarely, if ever, interact with people outside their family. Although many people may sometimes experience moments of isolation, hikikomori is a chronic state that becomes a lifestyle.

Looking at the gender aspect, the problem seems to affect more men than women, though exact figures vary. Some studies suggest that men might be more vulnerable to the social and cultural pressures typical of Japanese society, leading them to withdraw.

Although hikikomori is most widespread in Japan, the phenomenon isn't confined only to this country. Reports point to similar cases of isolation in other Asian countries like Korea and Hong Kong, and even in Western countries like the USA, Australia, and European nations. In Hong Kong, it's estimated there are over 100,000 hikikomoris. Global research on this phenomenon is still ongoing, but it has become clear that hikikomori is a problem with a much broader scope than initially thought.

Popular Myths and Stereotypes about Hikikomori

Hikikomori vs. Otaku: Hikikomori are individuals who have withdrawn from social life, often not leaving their room for many months or years. In contrast, otaku are enthusiasts of certain subcultures, such as manga, anime, or video games. Although otaku may spend a lot of time on their hobbies, they don't avoid social interactions in the same way as hikikomori.

Other Concepts: There are other terms that might be confused with hikikomori, such as agoraphobia (fear of open spaces) or depression. While hikikomori might suffer from these conditions, their main characteristic is prolonged social withdrawal.

Media Stereotypes: The media often depicts hikikomori as lazy, quirky young people who refuse to grow up. However, this image is a simplification. In reality, many suffering from hikikomori face serious mental issues leading to isolation.

Hikikomori in Anime: In popular culture, especially in anime, hikikomori are often portrayed as eccentric characters with unique abilities or secrets. While this representation might be appealing to viewers, it doesn't provide a complete picture of the issue. To effectively assist those affected by hikikomori, it's important to understand their situation and differentiate fact from fiction. Equating them with otaku or NEETs is unfair and hinders the identification of effective solutions for those genuinely in need.

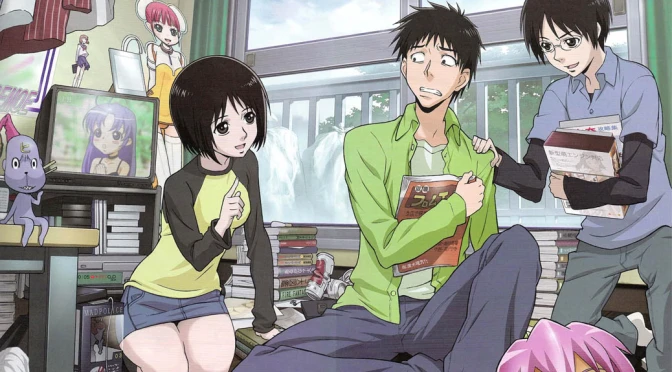

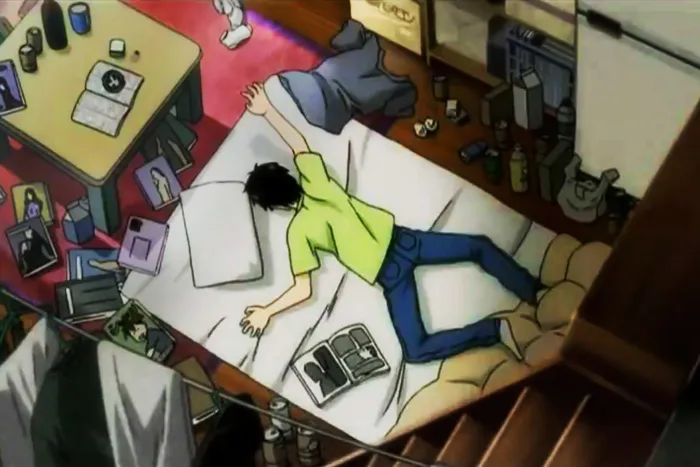

Hikikomori in Anime World

"Rozen Maiden": In the anime "Rozen Maiden", the main character Jun Sakurada is a young man suffering from hikikomori after a traumatic school experience. His isolation is portrayed as a defensive reaction to the external world, but everything changes when he receives a mysterious package containing a doll.

"Watamote: No Matter How I Look at It, It’s You Guys' Fault I’m Not Popular!": While the main character Tomoko Kuroki isn't a classic hikikomori, her intense social anxieties and difficulties in establishing peer contacts are often associated with hikikomori characteristics. In one episode, Tomoko tries to survive 50 days without leaving her house during summer vacation.

"Recovery of an MMO Junkie": Moriko Morioka, the lead character, is a 30-year-old woman who quits her job and becomes a NEET, predominantly spending her time playing online games. Although not a typical hikikomori, her life of isolation and avoiding the real world echo this phenomenon's characteristics.

In anime, hikikomori are often empathetically depicted, showcasing their internal struggles and challenges. Nonetheless, it's essential to remember that anime is a form of entertainment, and the reality of those suffering from hikikomori can be much more complex than portrayed in these stories.

The age and aging issue in the context of hikikomori

Not Just the Young: While the phenomenon of hikikomori is often associated with adolescents and young adults, older individuals are not exempt from this issue. There is a growing group of middle-aged individuals who also experience the social isolation typical of hikikomori. In fact, many experts highlight that hikikomori who began their isolation in youth often continue this lifestyle into old age.

Social and Health Implications of the 8050 Problem: When the parents of hikikomori reach a very old age or pass away, their isolating children often lack the means or ability to live independently. Many have no work experience or struggle with basic daily tasks. Moreover, caring for an aging parent can increase health risks for the hikikomori, such as depression or chronic illnesses. This presents a significant burden on Japan's healthcare system and raises questions about the future of these individuals in society.

Future Perspectives: With the aging of the Japanese society, the 8050 problem is becoming more pressing. The Japanese government has taken some measures, such as launching support centers for hikikomori, but a more comprehensive approach is needed. Many experts stress the need for early intervention, public education, and family support to prevent this crisis from escalating in the future.

Challenges in Treatment and Support for Hikikomori

Apart from "rental sisters", there are also other forms of support for hikikomori, such as individual therapy, support groups, and specialized centers for those who isolate. The Japanese government also runs initiatives to assist in their reintegration, including setting up support centers and educational programs.

People who have spent many years in isolation often encounter numerous challenges when reintegrating. The lack of work experience, education gaps, and lack of social skills make returning to "normal" life exceptionally hard. Many hikikomori feel overwhelmed by daily responsibilities like work or social interactions, leading often to relapses into isolation.

Hikikomori on a Global Scale

Various countries have begun to notice similarities between their instances of social isolation and the Japanese hikikomori. For example, in South Korea, the term "hikikomori" has been adapted as "hwabyeong", describing young individuals isolating themselves in their rooms for years. In the USA and Europe, there's also a growing number of youths withdrawing from social life, though they often don't directly identify with the term "hikikomori".

Although reasons for social isolation can vary depending on culture and society, the global rise in this phenomenon indicates the need for deeper analysis and understanding of its roots. In many countries, factors like social pressure, competition in education and job markets, and changing social roles might contribute to the increase in people retreating from public life. Governments and organizations worldwide are starting to address this issue and search for effective treatment and support methods for those affected.

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!