Songs from the Eta-mura – The Lives of the “Non-Humans” Erased from the Maps of Shogunate Japan

Japan from Below

A person was born eta and died eta (穢多 – “filled with impurity”). Yet, in the eyes of the shogunate’s law, he was not considered a person at all. A boy was born to be a tanner, an executioner, or a gravedigger, and he would die worn down by a prematurely aged body, never having known any other trade. A girl would marry within the same settlement, never crossing its boundaries. Entire generations knew only a handful of clay huts, the stench of tanned hides, and the rhythm of women’s songs sung in an archaic dialect unintelligible to “real” Japanese.

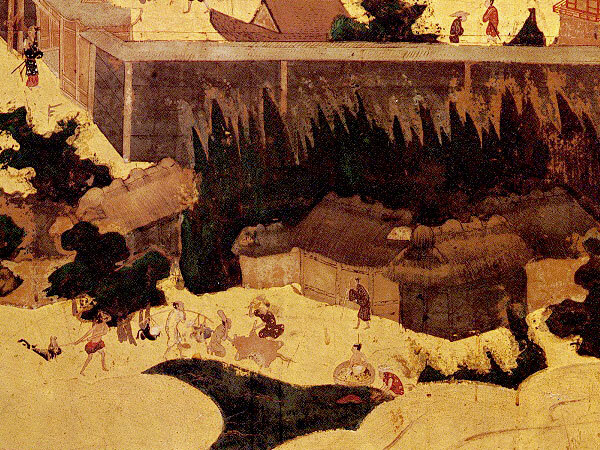

The men tanned hides, gutted animal carcasses, and the smoke of burning remains, mixed with the acrid scent of tanning workshops, hung above the settlement like an indelible mark. They crafted taiko drums, which would later be used in Shintō shrines and at the grand festivals of Edo – though those who played them would never look their makers in the eye. In their hands were born objects without which Edo-period Japan could not have existed, and yet society pretended that they themselves did not exist. Every step, every breath, every touch was marked by taboo.

In this parallel Japan, there was no mobility; dreams were as narrow as the interior of a hut, and the space of life ended at the horizon of the settlement. A child knew their place from birth: the world was divided into the “pure” and the “impure,” and that boundary was never crossed. It was an excluded Japan and yet inseparably tied to the rest of the country – hidden beneath its structures like the roots of a tree that nourish the trunk even as they themselves remain buried in darkness. To truly understand Edo culture, one must also listen to the voices that were silenced for centuries: in the songs of women, in the murmur of settlements absent from the maps, in the languages born on the edge of taboo.

Today, we enter the culture of this other Japan – the culture of the etamura villages – of the “full of impurity,” the “non-humans” cast beyond the boundaries of Tokugawa Japan’s society.

The Other Japan

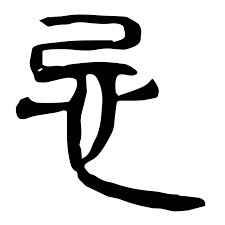

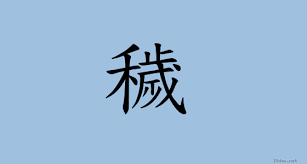

The silence there was different from the stillness of early morning in Edo – not the serenity of zen, but something denser, as if the very air carried the awareness of being “elsewhere,” outside the world that claimed to be real. This was an etamura village – a village of the impure. These were not Japanese, though they spoke Japanese. More than that – in the eyes of Edo’s inhabitants, in their language, and ultimately even under the law of the shogunate – they were not even human. Hinin (非人 – literally, “non-humans”).

A young boy named Genjirō sat on the threshold of his home – a modest hut of unplaned wooden boards, covered by a dark, worn thatched roof. All houses in the etamura looked alike: small, tightly clustered together, with bare earth floors and often no separate rooms. Sitting cross-legged, Genjirō sharpened a small knife for skinning animals. Beside him lay a bowl filled with salt and ash – a mixture used to cleanse blood from hands and tools.

Genjirō glanced toward the square at the center of the settlement, where the village elders (men over thirty – the average life expectancy of these “non-humans” was low) were gathering for the morning meeting. Above the entrance to the headman’s house hung a small wooden plaque carved with the kanji "清" (sei, “purity”). It was an irony – purity had little to do with how Edo society viewed them. To others, they were 穢多 (eta), “full of impurity,” because they dealt with things Shintō and Buddhism considered defiled: blood, death, corpses.

In front of the houses, deer hides dried in the sun as women softened them with fish oil, using short wooden mallets. Some women sat with children by small hearths, singing old songs about their ancestors – songs unintelligible to outsiders, for they were sung in a dialect interwoven with archaic words and secret terms related to their craft. The language of the etamura itself was like a barrier. It was still Japanese – but little of it would be understood by an Edo townsman, a “real person.”

Society rejected them, yet could not function without them. A paradox – one of many found in human societies across the world. Of course, Genjirō knew nothing of this – education (beyond the family craft) in these excluded villages was virtually nonexistent, and the horizon of their thoughts could scarcely stretch beyond the boundaries of the etamura.

In the afternoon, the young boy helped his father with tanning. They stood beside wooden vats filled with a mixture of ash, water, and tree bark extract. The sharp, acrid smell burned their nostrils, and their hands swelled from constant soaking in the solutions. Sometimes, Genjirō laughed quietly at how their bodies smelled of the settlement itself – a scent that betrayed every eta even in a crowd in Edo.

In the evening, as the sun sank behind the marshes, the people of etamura gathered around the fires. Women told children stories of long ago, and the elders recited songs that were never written down – passed instead in whispers from generation to generation. They spoke of kegare – spiritual impurity – but in their tales, the word held a meaning different from Edo’s. For Genjirō and his people, kegare was no shame; it was natural, part of life itself, a cycle of birth, death, and purification.

Within the etamura lay a profound paradox – a world that officially did not exist, yet one that was irreplaceable. To Edo, they were “unclean,” “other,” but in the quiet of the evening fire, in the beat of the taiko drum, in the whispered songs of old, there lived a parallel culture, full of its own rituals, beliefs, and values.

This was the other Japan – unrecorded in chronicles, yet more enduring than those who once sought to erase it from history. A second culture carried by the archipelago, even if the shogunate’s society refused to carry it within “its” Japan.

Society of Edo-Period Japan

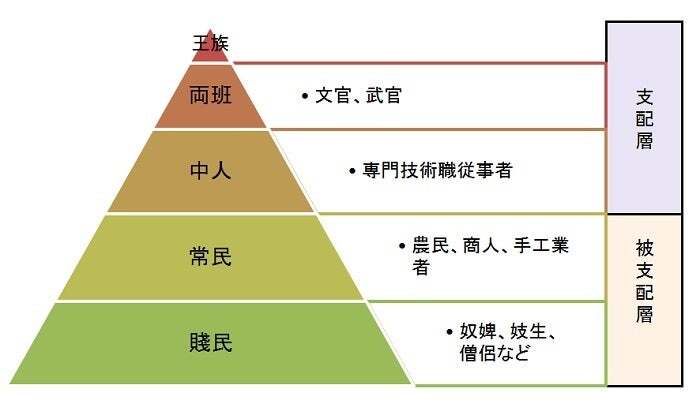

The Four Classes – shinōkōshō (士農工商)

All of this followed the system of shinōkōshō (士農工商) – the four official social classes – a structure rooted less in economics than in ideology.

Below them were the peasants (農, nō), also called nōmin (農民), regarded as the foundation of the entire state (here, the attentive reader might note a difference from Europe). From their labor came rice – the true measure of wealth, taxation, and prestige in Edo-period Japan. It was no exaggeration to say that every grain of rice in the shōgun’s bowl began in the fields of the nōmin. They constituted about 80% of the population and, though ranked below the samurai, they enjoyed a relatively high moral status – they were seen as the nation’s sustainers. Yet their lives were far from idyllic: heavy taxes, recurring famines, the constant risk of uprisings, and the tight control of feudal lords made them as dependent as they were indispensable.

At the very bottom of the system – which may surprise the European reader – were the merchants (商, shō), ironically ranked the lowest and yet often the wealthiest. Within the framework of Confucian ethics, they were regarded as “parasites” – people who created no value but merely traded in it. And yet, it was they who gradually came to control much of the wealth of the era. Declining samurai families sometimes fell into debt to rich merchants (who occasionally went so far as to purchase samurai status for themselves).

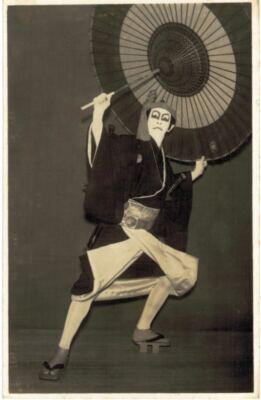

The streets of Edo were lined with machiya – elegant merchant houses where silk, sake, and ceramics were sold. Beneath the façade of low status, vast fortunes were born, enabling these merchants to finance kabuki theaters, ukiyo-e woodblock prints, and the pleasures of Edo’s entertainment districts. This ironic tension between rank and wealth became one of the driving forces behind the cultural explosion of the Edo period.

Few realize that much (though not all!) of what we consider quintessentially “Japanese” today originates not with the samurai but with the merchant class: the aesthetic of mono no aware, ukiyo-e, the flourishing of kabuki culture, the development of haikai poetry and the works of Bashō, the fashion for luxurious kimonos and yūzen patterns, even the yakuza honor codes (more on machi shū here: Honor Did Not Belong Only to the Samurai – Bravery, Courage, and the Ethos of Life of the machi-shū). And the great masters of ukiyo-e? Hokusai was the son of a mirror craftsman; Hiroshige, the son of a firefighter.

And yet, even this tightly ordered hierarchy, rooted in a Neo-Confucian worldview, did not encompass everyone. Beyond its margins existed a world that Edo preferred to keep silent about. For there were Japanese who did not fit into any of these four classes.

Outside the System: eta, hinin, burakumin

Beyond the official structure lived those referred to as mibun gaijin (身分外人) – “people without status.” Their presence was both indispensable and invisible: they handled the “unclean” aspects of Edo life while being pushed outside society, beyond the city limits, into their own enclaves known as buraku (部落 – literally “segregated district”) or etamura (穢多村 – “village full of impurity”).

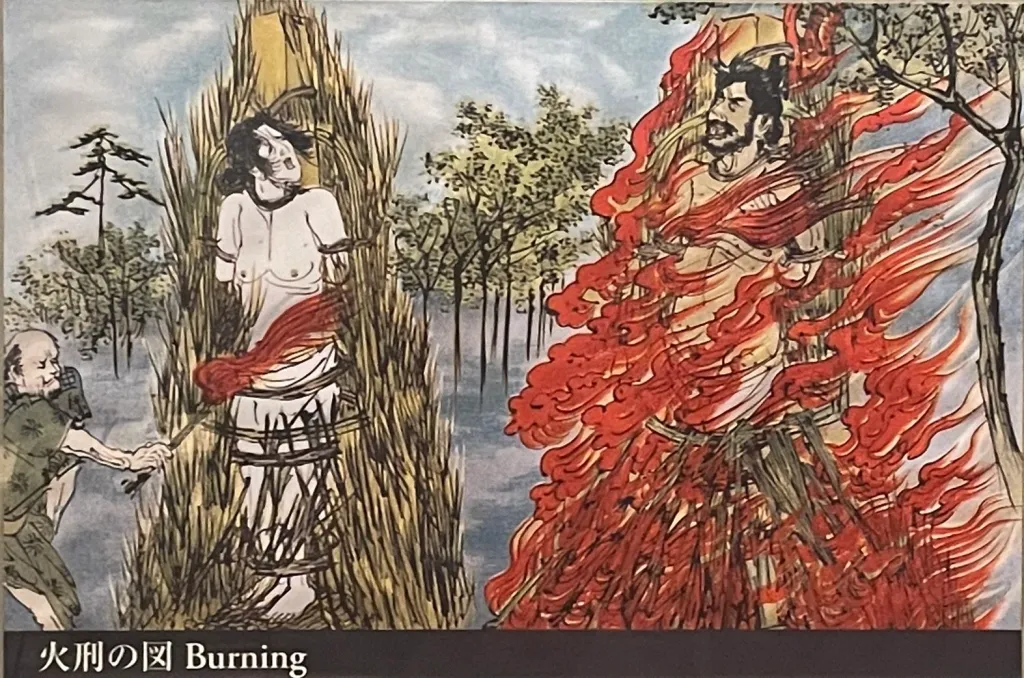

Even lower in this unspoken hierarchy were the eta (穢多), a term literally meaning “abundance of impurity” (e – “impurity,” ta – “many”). These were primarily butchers, tanners, drum-makers, bow-makers, and those who worked with bodies – animal or human. Their status was hereditary and inescapable: they could not leave their communities or marry beyond them. In return, they monopolized certain trades – supplying hides for armor and footwear, wood for execution stakes, and sometimes even building the gallows themselves. In Edo, entire families of eta were known by name, carrying out the same “unclean,” yet essential tasks across generations.

Though Edo officially projected an image of a homogeneous society, in reality, there were two Japans: the “pure” one, draped in the façade of harmony, and the “impure” one, cast beyond the city’s boundaries, yet inextricably intertwined with its fate.

Without the eta, there would have been no samurai armor, no temple drums. Without the hinin, there would have been no executions, no burials, no clean canals or orderly streets. This was a mirror culture – invisible, yet omnipresent.

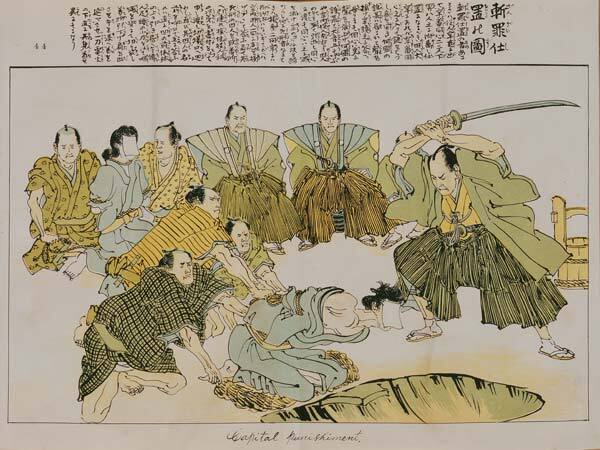

Night Work

At the entrance to the village stood Kanzaemon, a middle-aged man with a face carved by deep wrinkles. He was one of the eldest oshiokinin (御仕置人 – executioners), those tasked with carrying out sentences of death. Though his role was essential to Edo society, the “clean” folk from the nearby village treated him, at best, like a repulsive outcast. More often, they simply pretended he didn’t exist, turning their heads away as he passed. Even his shadow was thought to be defiling; people took care to avoid letting it fall upon them. Kanzaemon knew no other life – it had been this way for as long as he could remember. His father, and his grandfather before him, had also been oshiokinin. His son would be, too.

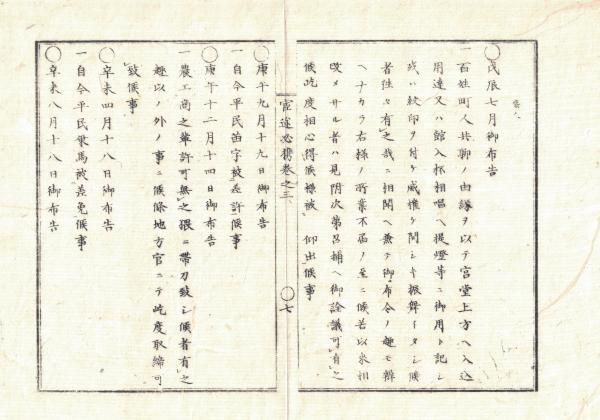

That day, an inspector from Edo Castle had arrived at the etamura. In his hand, he carried scrolls of washi paper – an order to prepare the execution grounds for a captured thief. Kanzaemon listened in silence, a small group of villagers gathering behind him. Some whispered among themselves; others spat quietly into the dust – executions meant more work. Within the settlement, such events were marked by complex rituals: the wood for the scaffold had to be brought from specific forests, and the executioner was required to undergo a cleansing fast accompanied by the recitation of prayers in an archaic dialect.

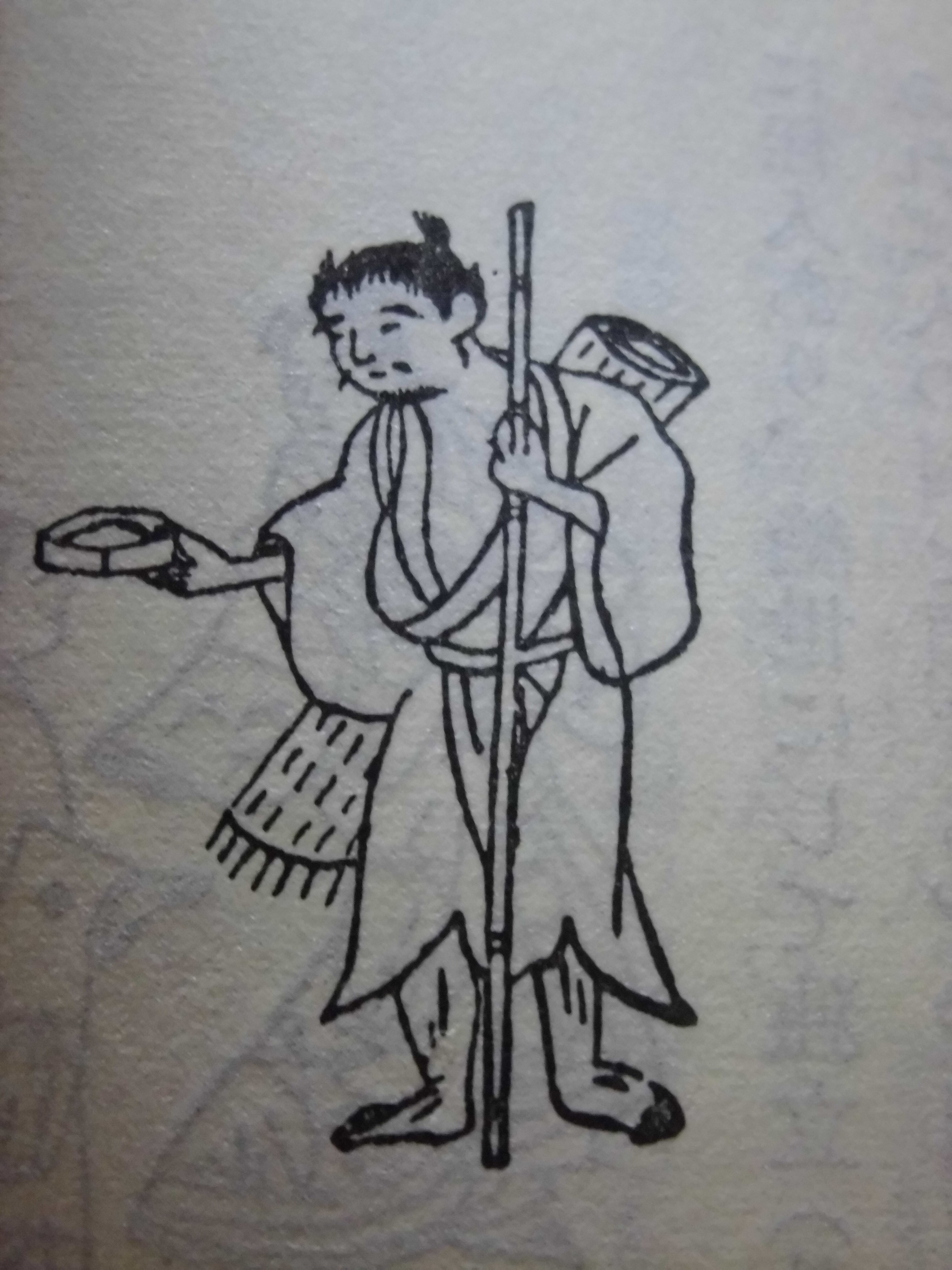

Though the village was closed off, news of the outside world always found its way in. It was often brought by wandering actors and jugglers, themselves excluded from the official caste system. They brought color and illusion to the life of the etamura, telling tales of Yoshiwara’s splendor, the latest fashions of Edo, or the bloody peasant uprisings – and the shogunate’s even bloodier reprisals. In exchange for gossip and stories, they received a meal, a rabbit pelt, or a small coin.

Later that night, beneath a black sky with the moon hanging high, the villagers gathered around a fire as the elders read aloud passages from their family records. These scrolls, kept for generations, recorded who married whom, which crafts passed from father to son, and which families had once been granted the “favor” of the shogunate, allowing them slightly better living conditions. In the glow of the flames, the children listened with wide eyes – this was their history, their tradition, their culture – more important than any distant shogunal decrees.

Though to the outside world, separated by a ring of bamboo groves, the residents of the etamura were “unclean,” here everyone knew their place, the names of their ancestors, and the songs that had been sung for centuries. This was a parallel Japan – a distinct culture whose existence barely broke through the walls of silence.

Naming and Origins

Contrary to common misconceptions (especially among Japanese themselves; in Poland, such notions are rare), today’s burakumin are not simply “direct descendants” of those early slaves. However, it is within the category of senmin that we find the cultural roots of later exclusion. Over the centuries, these marginal groups transformed and diversified, laying the foundations of a separate culture that would develop in parallel to “official” Japan.

There, far from the settlements of the ryōmin, arose the first embryonic communities that would later be called etamura – villages of the excluded, absent from official maps and long ignored in population registers.

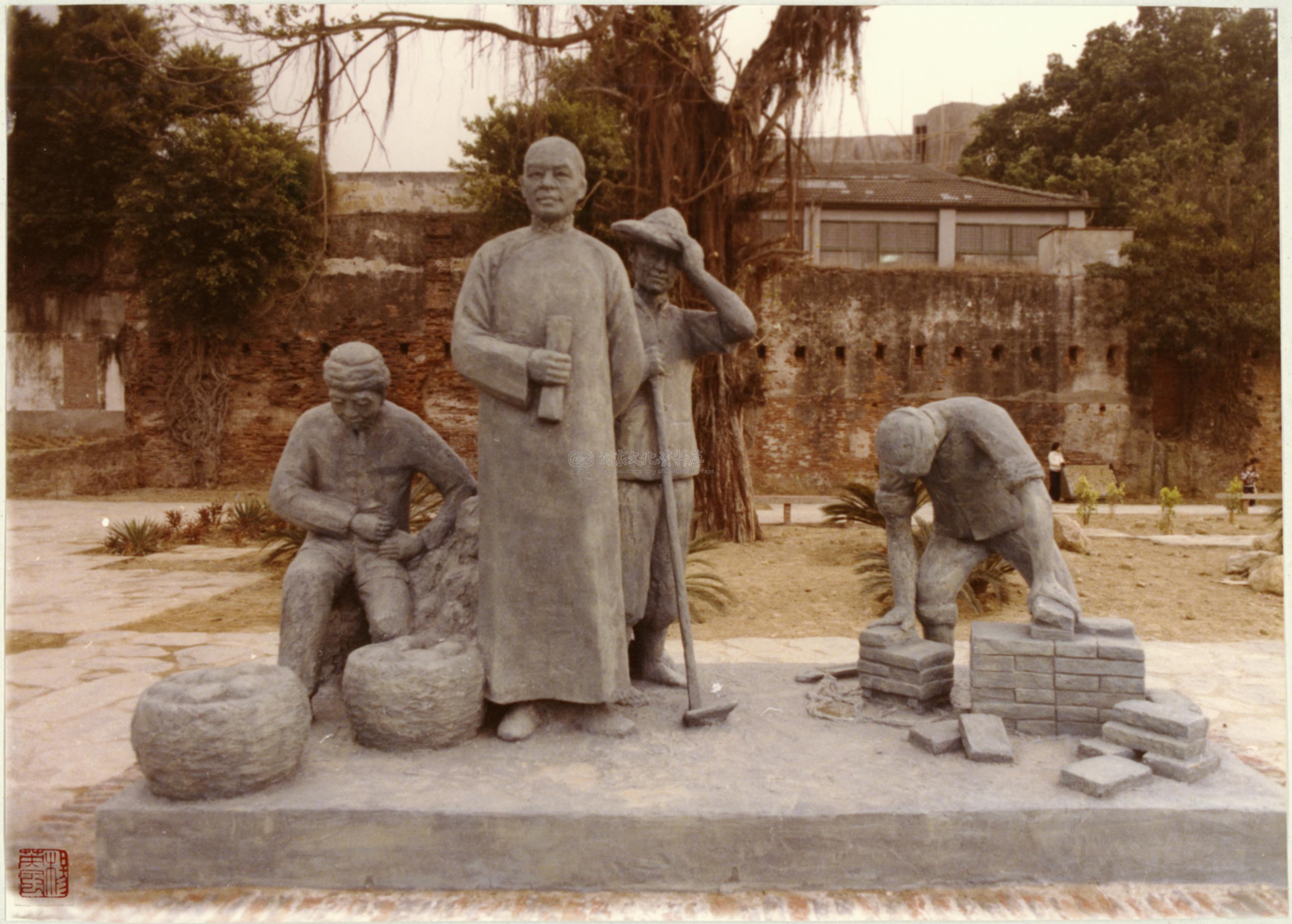

Yet these communities were far from chaotic. In certain regions, local leaders known as eta-gashira – “heads of the eta” – held considerable authority. The most famous of these, Danzaemon of Edo, wielded real power over an entire network of etamura in the Kantō region: he appointed executioners, organized the production of hides and bones, and even negotiated taxes and obligations with the shogunate on behalf of his people.

This paradox – of being both “invisible” and utterly indispensable – makes the eta and hinin among the most fascinating groups in the history of Edo-period Japan.

Everyday Life and the Elements of the “Second Culture”

Occupations and Economy

Shogunate records from the mid-18th century preserve striking data: in some regions of Kantō, as much as 70% of the leather used in Edo came from the network of etamura overseen by a single authority – the renowned Danzaemon.

Among the rivers, on the edges of towns, one could see their workshops, where wet hides hung from wooden racks and the air was heavy with the pungent smell of tanning. The eta maintained a closed economic system: leather was precious, but it was sold through intermediaries, never directly to the “clean” merchants who wished to avoid defiling their hands through contact with “impurity.” Prices were negotiated discreetly and at length, often with the eta-gashira, the village leader, acting as the chief negotiator.

Thus, within Edo’s economic structure, there existed a paradox: those whom the “clean” world avoided provided it with the tools, the entertainment, and the materials it could not do without. At the crossroads of these two Japans – the official and the excluded – a culture was born that remained invisible for centuries.

Customs, Language, and Rituals

Funeral rites differed greatly from those of the “clean” ryōmin. Major temples often refused to accept the bodies of the eta and hinin, leading to the establishment of separate cemeteries, divided from the “true” land of others by symbolic stakes made from white branches. Strict purification rituals governed these practices: before returning from a funeral, mourners would pass through juniper smoke or rinse their hands with water poured into bowls carved from ash.

Adaptation

These communities also celebrated their own festivals – modest yet laden with symbolism. During them, prayers were offered to local kami for abundant harvests, good health, and protection from floods, while participants sang songs and danced to the rhythms of drums whose sound was never heard beyond the settlement’s edge. It was a world unto itself, where traditions endured for centuries, untouched by the will of the shogunate.

The End of the Eta?

Symbolically, this marked the dawn of an era of equality, a time when the old hierarchy was meant to dissolve and every inhabitant of Japan, regardless of birth, was to stand equal before the law. But history is rarely so simple, and words written in ink do not always reach into the fabric of daily life.

The edict abolished the law but did not erase memory. The former etamura – villages of the excluded – still existed where they had always been: on the city outskirts, along rivers, in the shadows of wealthier districts. Even if, on paper, the boundaries of status had disappeared, in people’s hearts and minds they remained clear. The most potent instrument of this invisible segregation became the koseki (戸籍) – the family registry system. A mere glance at a birthplace was enough to infer origins. The land once inhabited by the eta and hinin carried its own stigma: an address could weigh heavier than a name. In official documents, legal status was equal, but in the eyes of society, divisions older than the shogunate endured.

Perhaps this is the essence of the story: true equality is not born in edicts but in the consciousness of people. Community requires more than new names; it demands the labor of memory, an understanding of history, and the acceptance of its weight.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era

Kabukimono Longing for War: Free Spirits, Deadly Rogues, and Madmen in Women’s Kimonos

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!