Honor Did Not Belong Only to the Samurai – Bravery, Courage, and the Ethos of Life of the machi-shū

Once again, Western pop culture got everything tangled up

The ethos of machi shū was born not in the shadow of banners, but in the glow of lanterns hung before the home. Instead of the battlefield—there was the workshop; instead of a knightly death—responsibility for the common good. It was in neighborhoods ravaged by fire, during epidemics, in times of crisis and famine, that the civic courage of everyday life was forged—quiet, practical, yet deeply heroic. Machibikeshi—community firefighters—would climb onto burning houses to dismantle roofs and block the path of the fire; craft guilds would gather rice and firewood for those who lost everything; elderly women would teach orphans how to survive. Ritual, discipline, aesthetics—all of this formed a coherent world of values in which loyalty was horizontal, not vertical: it was directed not toward a lord, but toward a neighbor, and honor was measured not by the sword, but by action. It was machi shū—not the samurai—who were the authors of most of the aesthetic forms of the era: ukiyo-e, kabuki, haikai poetry, urban wabi. They shaped Japanese everyday life—organized, disciplined, full of respect for the beauty of simple things.

Today, their spirit endures, responsible for the fact that crime in Japan is practically nonexistent. Even in the most unexpected places. The yakuza, to whom pop culture attributes samurai origins, is in fact a peripheral continuation of machi shū. Their ethos—though often distorted and entangled in criminality—is based on loyalty to the group, a strict internal code, brotherhood, and communal rituals. There is a code of honor here—but distant from the samurai one—closer instead to machi shū. In place of the district—kumi. In place of the elders—oyabun. It was not the world of the samurai that created these values, but the world of urban chonin, whose culture—marginalized in pop culture narratives about warriors—proved to be more enduring, more human, and more understandable. This text is about them. About the values of bravery, courage, and responsibility in life, not in death.

Who Were the machi shū?

The Name

- 町 (machi) – a district, street, but also the basic unit of urban organization. As early as the Heian period, it referred to a city block, and in medieval Kyōto—to a self-governing community of residents in one part of the city.

- 衆 (shū) – people, group, collective. It appears in ancient Japanese Buddhist and Confucian texts, carrying the meaning not of a mass, but of a community bound by ritual, function, and neighborhood. It does not simply mean “people,” but something closer to a community (though not necessarily in our modern, internet-era sense).

The expression machi shū appears in sources as early as the Sengoku period, especially in the context of Kyōto—residents of districts at the time formed grassroots temple municipalities, organized their own guards, and gathered funds for common goals. Though it was not yet a unified formation, from these local communities emerged a culture that would blossom in Edo as a fully-fledged ethos.

▫ 町人 (chonin) – literally “people of the district”; merchants and artisans who formed the foundation of urban society and from whom members of machi shū were drawn.

▫ 町奉行 (machi bugyō) – bakufu officials responsible for the administration of districts, public order, and civil affairs in the cities.

▫ 五人組 (goningumi) – a system of five-person neighborhood groups, in which each person was responsible for all the others; the cornerstone of social control and local loyalty.

▫ 町年寄 (machi doshiyori) – district elders, chosen from among distinguished townspeople, serving representative, organizational, and mediating functions.

These terms show that machi shū was not a loose gathering of city folk but a consciously built fabric of urban community, governed by its own rules—parallel to the samurai structures, but just as coherent and influential.

History

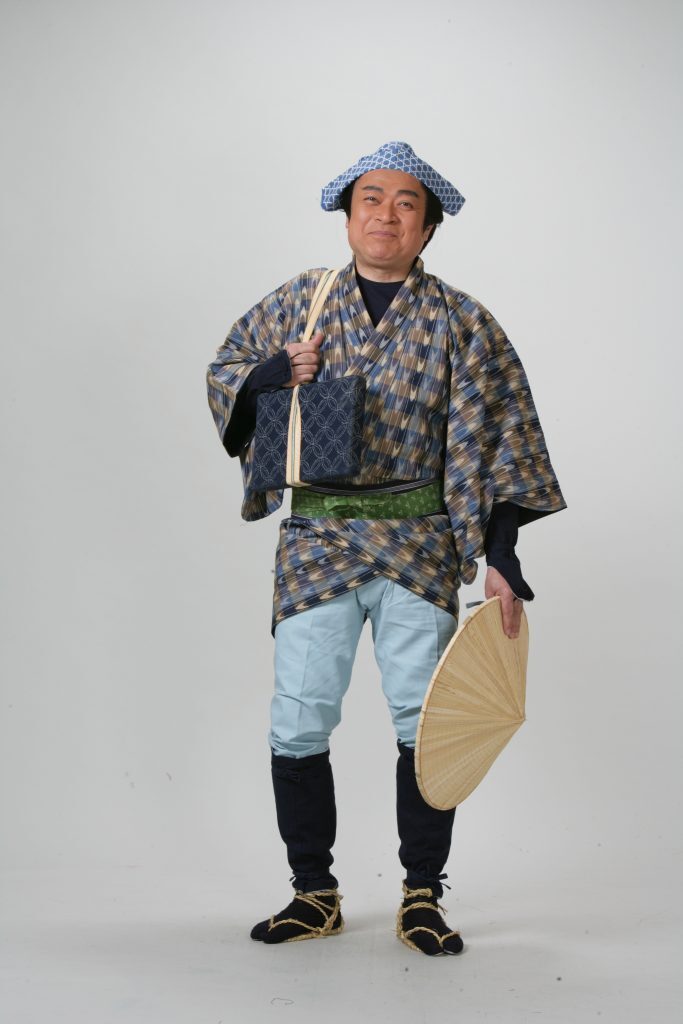

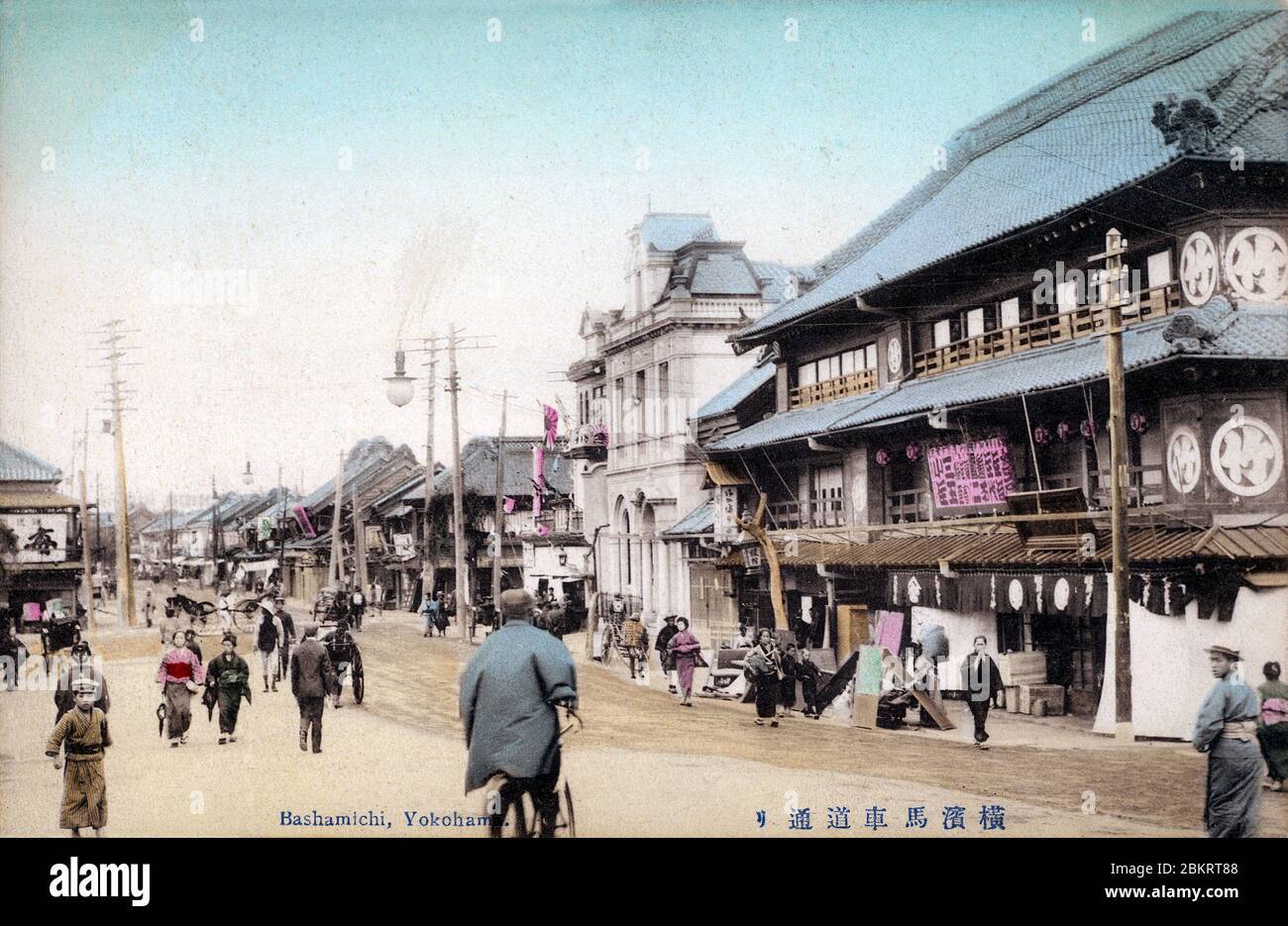

But it was not until the Edo period (1603–1868) that this culture truly flourished. During this time, cities exploded in population—Edo became the largest metropolis in the world—and the chonin (町人) community of artisans and merchants gained strength, despite occupying the lowest official rung of the feudal hierarchy. It was they—the chonin—who formed the core and backbone of machi shū. In their workshops, tea pavilions, kabuki theatres, and neighborhood festivals, an alternative code of life was forged—not based on loyalty to a lord, but on solidarity with neighbors, diligence in work, responsibility for the common good, and care for one’s reputation.

It’s important to emphasize: machi shū were not a social class in the European sense—they were not defined by birth, but by function within the urban community. Among them were wealthy traders and poor craftsmen, firefighters, old guild masters, and young apprentices. What united them was an ethos—an ethical and aesthetic community that can be described as “honor without the sword.”

A Brief History

How Did the Culture of machi shū Come into Being?

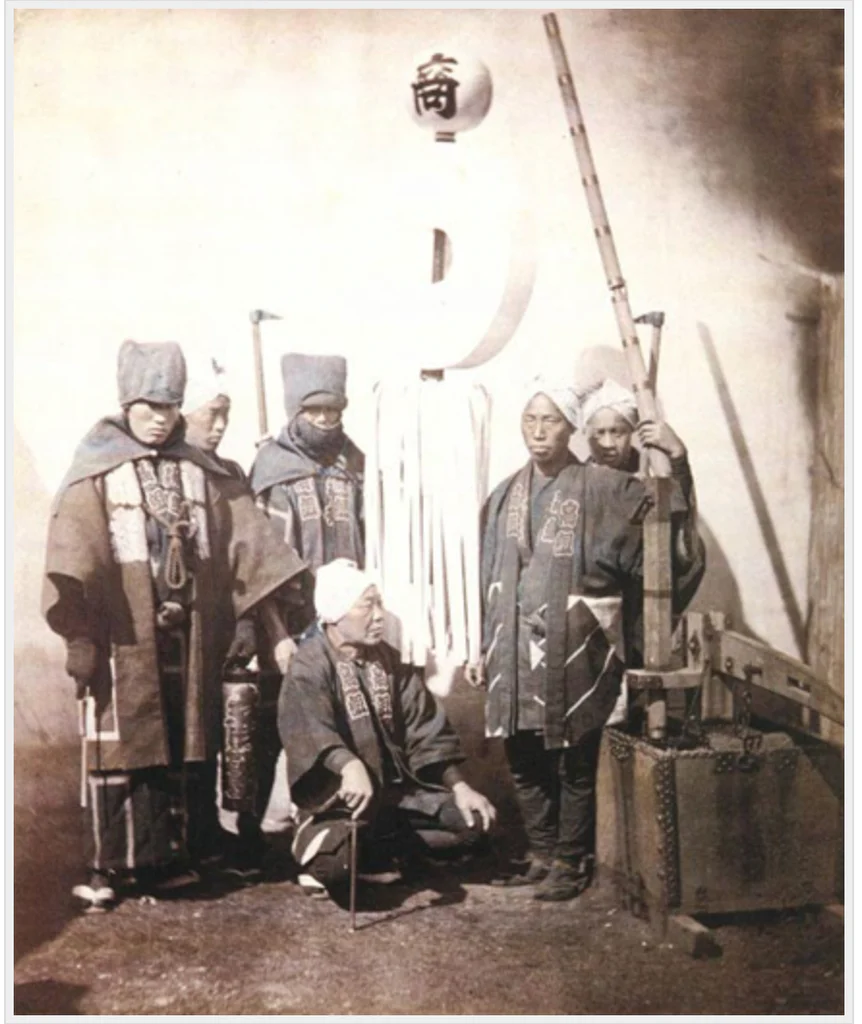

It is also impossible to overlook the role of volunteer fire brigades—machibikeshi (町火消し). Their members—often young, strong artisans—risked their lives climbing onto rooftops in burning districts to dismantle parts of the buildings and stop the spread of fire. Their uniforms, rituals, and iconography (such as the great matoi—unit banners) show how deeply civic bravery—not military valor—was inscribed into the urban ethos. Fire was not a catastrophe to them—it was a moment of trial.

Over time, the machi shū culture also developed artistic patronage that defined the aesthetics of the era: ukiyo-e, kabuki theater, fashionable crafts, haikai poetry, and tea ceremonies based on urban wabi. It was not the aristocracy or the samurai who were the primary audience for this culture—but precisely the chonin and their communities, who in Edo created an alternative model of Japanese life—urban, organized, full of discipline, but also deeply sensual.

Thus, from the uncertainties of the Sengoku period to the maturity of the Edo era, the culture of machi shū was born—an informal republic of city people, governed by the honor of community, the aesthetics of simplicity, and the quiet courage of everyday life.

The Honor Code of machi shū

The central value was loyalty—but not to authority or feudal overlords. The loyalty of machi shū was directed toward horizontal bonds: to the guild, to the kumi (neighborhood group), to the kō (pilgrimage brotherhood), to the family, which extended beyond blood relatives. A person was part of a greater whole—the machi (district)—and to it they owed duties, and in it they sought protection. This was communal, not individual honor—broken by one, it brought shame upon all. Such a structure of bonds was both morally constructive and practical—the community watched over itself, protected itself, and resolved its own disputes.

In the realities of Edo, where cities built from wood and paper frequently burned, and canals became breeding grounds for epidemics, bravery did not mean fighting an external enemy but facing catastrophe—with a rope in hand, a bucket of water, a stretcher for the sick. Members of the machibikeshi, the fire brigades, climbed onto the roofs of burning houses to manually remove tiles and halt the fire’s progress. Brothers from the guilds organized collections for those who had lost their homes. Women brought rice and medicine to neighbors during cholera outbreaks. The courage of machi shū was daily, practical—unheroic in form, but heroic in essence.

(Do you admire modern Japan for its social discipline and near-zero crime?—if so, what you’re seeing is the echo of these values—still alive in twenty-first-century Japan.)

From this collective responsibility flowed other virtues of machi shū:

▫ Restraint – not in the sense of asceticism, but self-control: in speech, emotion, gesture;

▫ Reliability – the client was to receive exactly what they had ordered, without cheating or exploitation;

▫ Pride in one’s work – not merely as a means of survival, but as a source of identity (read more about shokunin here: An Hour of Complete Focus – What Can We Learn from Traditional Japanese Craftsmen, the Shokunin? and about iemoto here: Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era);

▫ Shitsuke (躾) – the discipline of daily habits, upbringing toward order, cleanliness, punctuality, modesty;

▫ Filial piety (kō, 孝) – extended not only to family, but also to the master of one’s craft, to the elder neighbor, to the local temple.

Machi shū in Action – Everyday Life in the Community

「江戸の花は火事と喧嘩」

(Edo no hana wa kaji to kenka)

“The flowers of Edo are fires and fights.”

One of the clearest examples of this urban courage was the volunteer fire brigades—machibikeshi (町火消し). In an era when homes were built of wood and paper, and the sources of light were oil lamps and hearths, fire was not just an element—it was public enemy number one. Fires in Edo were called “the flowers of the city” for good reason. In this reality, machibikeshi became the unofficial heroes of the districts, ready to leap onto burning rooftops with hooks and ropes to dismantle buildings and stop the flames. They wore colorful happi coats emblazoned with their brigade crests and marched in festivals bearing enormous matoi banners, inspiring admiration in children and women. Interestingly—membership in the brigade often passed from father to son, and some families built their entire social standing around this role.

A unique organizational achievement of machi shū was the creation of communal relief funds and care for those in need. When someone’s house burned down, they did not wait for help from the shogunate—it was the neighborhood that gathered rice, firewood, clothing, and money for them. Local support systems for widows and orphans also existed—both formal and informal. Elderly women in the district taught girls how to sew and cook, while boys were apprenticed to trusted artisans. No one was allowed to “fall out” of the community—because anyone who ceased to exist in the eyes of the district was like an empty house with boarded-up doors. Even in the case of mental illness or disability, care mechanisms were often created that—though primitive from our point of view—were full of compassion and practical concern.

It was precisely machi shū—not the samurai—who became the chief patrons of Edo-period popular culture. Kabuki, ukiyo-e, haikai poetry, even fashion—all of it arose thanks to the money and interests of the chonin. Kabuki theater was not a product of the aristocracy but entertainment for working people—merchants, carpenters, painters, textile traders. Actors were their idols, and performances often contained stories from district life, interwoven with morality tales and street humor. Ukiyo-e woodblock prints were produced in workshops functioning like small editorial offices: one artist, one carver, one printer—all rooted in their districts, known by name and face, supported by local sponsors.

Haikai—a form of poetry combining classical elements with sharp wit—flourished in circles of artisans and shopkeepers, who gathered in the evenings to improvise verses over sake. What we today call “Edo culture” was, to a large extent, the creation of machi shū—their laughter, their labor, their needs, their imagination.

All of this—from the communal well to the carved kabuki stage—formed a mosaic of everyday heroism that required no fanfare. The district was a world. And machi shū—its conscience, its arm, and its heart.

Machi shū and the Samurai

A Parallel Culture of Bravery

A Parallel Culture of Bravery

In the Western imagination, feudal Japan is often almost entirely identified with the samurai—the silent, honorable warrior, ready to give his life for his lord. This image, though striking, is fundamentally simplistic and deeply alien to our European experience. The samurai culture was extreme, anti-individual, based on the notion of service and death as the highest virtue. Bushidō—“the way of the warrior”—knew no right to live for oneself. It was a code that required a person to treat their own existence as a temporary tool of loyalty, ready for sacrifice at any moment. A world in which love could not outweigh duty, and in which beauty and death were the same.

Against the backdrop of this rigorous, almost inhuman ethic, the culture of machi shū appears not only as a contrast but as much closer to the modern understanding of bravery. The courage of city dwellers did not lie in the willingness to take their own lives (see: Samurai Seppuku: Ritual Suicide in the Name of Honor, or Bloody Belly Cutting and Hours of Agony?), but in the willingness to endure daily toil: to defend the community, maintain a family, and persist in the face of disaster. The ethos of machi shū was an ethos of life, not death. Responsibility, discipline, civic courage—these were its foundations. Where bushidō idealized solitary death, machi shū idealized collective life.

Many of them—especially those of lower ranks—lived on meager stipends, disconnected from warfare (during the Tokugawa shogunate, there were practically no wars anymore—with only minor exceptions), and were forced to perform civilian bureaucratic functions. Their reality bore little resemblance to the myth that defined them. More and more often, they looked with envy upon the chonin, the townspeople, who—although formally lower in the hierarchy—enjoyed real independence, cash flow, access to culture, and freedom of lifestyle. The samurai, bound to simplicity and loyalty, saw in the world of machi shū a freedom they themselves had never known.

This parallel existence of two codes—the warrior and the urban—was not a struggle, but a quiet dialogue, in which the machi shū slowly and imperceptibly took over the role of bearer of social values. For although the samurai had their code, it was not they who organized the everyday life of the city. It was the people of the districts—carpenters, traders, sculptors, doctors, firefighters—who created the practical rules of coexistence, the morality of daily life, and the rituals of mutual existence that lasted far longer than the banners of the samurai.

And this is precisely why machi shū feels so much closer to us Europeans today. Their values—community, diligence, loyalty to neighbors, dignity in a simple life—are understandable without needing to translate them from a different civilizational order. In contrast to the radicalism of bushidō, which may seem beautiful but is in truth wholly alien to us, machi shū reveals a Japanese face of humanity that we can still recognize as—so to speak—our own.

The Legacy of machi shū Culture

From Meiji to the Present

It’s also hard to miss this legacy in the structure of Japanese family businesses and corporations, which—though modern—often function like miniature Edo neighborhoods. They are hierarchical, based on loyalty, with their own daily rituals. Senior employees possess an almost paternal authority. Novices learn through observation and imitation. There are company shrines, shared office cleanings, morning roll calls, and anniversary celebrations. Even the idea of working “for the good of the team” has its roots in the Japanese machi no ishi—“the spirit of the district.”

That is why, when we look at contemporary Japan—the one made of concrete and neon, vending machines selling coffee and panties, and bullet trains equipped with more sensors than space probes—it is worth knowing that beneath this modern landscape, the heart of Edo still beats. Quiet, rhythmic, communal. The culture of machi shū may not have survived as a formal structure—but it lives on and thrives as something far more important: the values embraced by the Japanese people. In the neatly swept sidewalk. In the lantern hung before a shop. In the careful bow to a neighbor. Wherever daily life becomes a ritual—machi shū still lives.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Unidentified “Utsurobune” Object in the Time of the Shogunate – UFO, Russian Princess, or Yōkai?

Kabukimono Longing for War: Free Spirits, Deadly Rogues, and Madmen in Women’s Kimonos

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

A Parallel Culture of Bravery

A Parallel Culture of Bravery