Eternity through Destruction

There exists in the world a shrine that is deliberately torn down every twenty years. Not because it has collapsed, not because it has succumbed to time, nor because space is needed for a parking lot. Quite the opposite – the very moment the freshly completed building still gleams with newness, the priests already know when it will be leveled to the ground. Exactly twenty years later. Then, from the same materials, in the same form, a new one will rise beside it. And you know what? The Japanese in Ise have been doing this every 20 years for… 1,300 years. This is what Shikinen Sengū in Ise looks like – the oldest tradition of cyclical renewal in Japan, repeated without interruption since the 7th century. It was broken only once, and then only briefly – during the bloodiest years of the Sengoku civil war in the 16th century. The last one took place in 2013, drawing over 14 million pilgrims and visitors, and the next is already marked on the calendar – the year 2033.

There exists in the world a shrine that is deliberately torn down every twenty years. Not because it has collapsed, not because it has succumbed to time, nor because space is needed for a parking lot. Quite the opposite – the very moment the freshly completed building still gleams with newness, the priests already know when it will be leveled to the ground. Exactly twenty years later. Then, from the same materials, in the same form, a new one will rise beside it. And you know what? The Japanese in Ise have been doing this every 20 years for… 1,300 years. This is what Shikinen Sengū in Ise looks like – the oldest tradition of cyclical renewal in Japan, repeated without interruption since the 7th century. It was broken only once, and then only briefly – during the bloodiest years of the Sengoku civil war in the 16th century. The last one took place in 2013, drawing over 14 million pilgrims and visitors, and the next is already marked on the calendar – the year 2033.

The stage for this extraordinary practice is Ise Jingū – the spiritual heart of both Shintō and Japan. It is not a single shrine but an entire complex: from Naikū, dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu, to Gekū, where Toyouke – the deity of agriculture and abundance – is worshiped, along with a network of 125 smaller shrines scattered across the surrounding area. Empress Jitō inaugurated the first reconstruction in the 7th century, and since then every generation has repeated the cycle. In a landscape where stone pagodas and Buddhist temples were meant to symbolize permanence, Ise chose the path of paradoxical eternity – through conscious impermanence.

The stage for this extraordinary practice is Ise Jingū – the spiritual heart of both Shintō and Japan. It is not a single shrine but an entire complex: from Naikū, dedicated to the sun goddess Amaterasu, to Gekū, where Toyouke – the deity of agriculture and abundance – is worshiped, along with a network of 125 smaller shrines scattered across the surrounding area. Empress Jitō inaugurated the first reconstruction in the 7th century, and since then every generation has repeated the cycle. In a landscape where stone pagodas and Buddhist temples were meant to symbolize permanence, Ise chose the path of paradoxical eternity – through conscious impermanence.

And that is where its magic lies. For thirteen centuries, despite wars, disasters, modernization, and globalization, the Japanese have faithfully preserved the custom of rebuilding the sanctuary every two decades. It is more than conservation – it is an act of collective memory, a national ritual, and at the same time a philosophical reminder that true permanence is born from the rhythm of renewal. One could say that Shikinen Sengū is like a breath: inhalation and exhalation, reconstruction and destruction, birth and death, repeated endlessly. And perhaps it is precisely for this reason that Japan continues to astonish the world – teaching that one does not need to fight impermanence in order to preserve eternity.

And that is where its magic lies. For thirteen centuries, despite wars, disasters, modernization, and globalization, the Japanese have faithfully preserved the custom of rebuilding the sanctuary every two decades. It is more than conservation – it is an act of collective memory, a national ritual, and at the same time a philosophical reminder that true permanence is born from the rhythm of renewal. One could say that Shikinen Sengū is like a breath: inhalation and exhalation, reconstruction and destruction, birth and death, repeated endlessly. And perhaps it is precisely for this reason that Japan continues to astonish the world – teaching that one does not need to fight impermanence in order to preserve eternity.

Ise Jingū

If Japan has a spiritual heart, it beats beneath the ancient cypresses of Ise. The Ise Jingū complex, also known simply as “O-ise-san” (お伊勢さん), is not one shrine but a vast sacred expanse – as many as 125 sanctuaries scattered among the forests and hills of Mie Prefecture. Two of them are the most important: Naikū (the Inner Shrine) and Gekū (the Outer Shrine). In Naikū, hidden within a dense forest by the Isuzu River, Amaterasu-ōmikami – the sun goddess, ancestress of the imperial line, and the most important deity of Shintō – is enshrined (more about her can be found here: In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun – The Story of Amaterasu). In Gekū, on the other hand, Toyouke Ōmikami is worshiped, the kami of rice, fertility, and abundance, whose role is to provide heavenly sustenance to Amaterasu herself.

If Japan has a spiritual heart, it beats beneath the ancient cypresses of Ise. The Ise Jingū complex, also known simply as “O-ise-san” (お伊勢さん), is not one shrine but a vast sacred expanse – as many as 125 sanctuaries scattered among the forests and hills of Mie Prefecture. Two of them are the most important: Naikū (the Inner Shrine) and Gekū (the Outer Shrine). In Naikū, hidden within a dense forest by the Isuzu River, Amaterasu-ōmikami – the sun goddess, ancestress of the imperial line, and the most important deity of Shintō – is enshrined (more about her can be found here: In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun – The Story of Amaterasu). In Gekū, on the other hand, Toyouke Ōmikami is worshiped, the kami of rice, fertility, and abundance, whose role is to provide heavenly sustenance to Amaterasu herself.

The shrine at Ise has over two thousand years of history and has always been a destination for pilgrimage. For the Japanese, this is no ordinary shrine – it is a space where the sacred intermingles with daily life, and where past meets present. In the Edo period, true religious “booms” took place here: millions of people, often entire villages, set out on journeys to Ise as part of “okage mairi” (御蔭参り), mass pilgrimages during which the faithful believed that the gods themselves were calling them. It is said that during one such wave, as much as 20% of Japan’s population set out at the same time for Ise – an event resembling a religious festival on a nationwide scale.

The shrine at Ise has over two thousand years of history and has always been a destination for pilgrimage. For the Japanese, this is no ordinary shrine – it is a space where the sacred intermingles with daily life, and where past meets present. In the Edo period, true religious “booms” took place here: millions of people, often entire villages, set out on journeys to Ise as part of “okage mairi” (御蔭参り), mass pilgrimages during which the faithful believed that the gods themselves were calling them. It is said that during one such wave, as much as 20% of Japan’s population set out at the same time for Ise – an event resembling a religious festival on a nationwide scale.

Ise Jingū is also unique for another reason: it is inseparably tied to the imperial family. According to myths recorded in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Amaterasu bestowed upon her grandson Ninigi-no-mikoto the three sacred imperial regalia – the mirror, the sword, and the jewel – of which the mirror, Yata-no-kagami, is preserved to this day in Naikū. Every emperor of Japan symbolically traces his divine lineage back to Amaterasu.

Ise Jingū is also unique for another reason: it is inseparably tied to the imperial family. According to myths recorded in the Kojiki and Nihon shoki, Amaterasu bestowed upon her grandson Ninigi-no-mikoto the three sacred imperial regalia – the mirror, the sword, and the jewel – of which the mirror, Yata-no-kagami, is preserved to this day in Naikū. Every emperor of Japan symbolically traces his divine lineage back to Amaterasu.

It is no wonder, then, that through the centuries Ise was called the spiritual capital of Japan – a place that does not yield to fashion or the times, because it always represents what is most important for the Japanese: gratitude toward nature, remembrance of ancestors, and the pursuit of harmony between the human and divine worlds. Today it is visited annually by about 8 million people – believers and non-believers, Japanese and foreigners alike – who wish, if only for a moment, to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of ma, that silence-filled space where the ordinary meets the extraordinary.

The Idea of Cyclical Renewal – What is Shikinen Sengū?

If someone asks what sets Ise Jingū apart from all other Japanese shrines, the answer is: Shikinen Sengū (式年遷宮). It sounds solemn, almost like the title of an ancient code of law, but in reality it denotes one of Japan’s most fascinating traditions – the cyclical reconstruction of the shrine every twenty years.

The etymology is quite telling. Shikinen (式年) means “fixed years” or “designated cycle,” while Sengū (遷宮) literally means “the transfer of the palace [for the deity].” In practice, it refers to transferring the divine presence (shintai) to a freshly built sanctuary standing right next to the old one. Every two decades, both Naikū and Gekū are rebuilt anew from fresh timber, and the goddess Amaterasu is ceremonially moved in a nocturnal procession to her new dwelling. One might say that in Ise the gods have a subscription to eternal freshness.

The etymology is quite telling. Shikinen (式年) means “fixed years” or “designated cycle,” while Sengū (遷宮) literally means “the transfer of the palace [for the deity].” In practice, it refers to transferring the divine presence (shintai) to a freshly built sanctuary standing right next to the old one. Every two decades, both Naikū and Gekū are rebuilt anew from fresh timber, and the goddess Amaterasu is ceremonially moved in a nocturnal procession to her new dwelling. One might say that in Ise the gods have a subscription to eternal freshness.

This tradition reaches back to the 7th century, a time when Japan was only beginning to shape its statehood. Its origins are traced to Emperor Tenmu (673–686), who wished that the divine residence would never fall into ruin. His wife and successor, Empress Jitō, organized the first Shikinen Sengū in the year 690. And so began something that has endured without interruption (save for a brief pause in the turbulent Sengoku period) for over 1,300 years.

The symbolism of the entire ritual is profoundly Japanese. On the one hand, there is the idea of mujo (無常), the impermanence of all things. Even the most sacred shrine, built from the finest hinoki cypress, ages and decays. On the other hand, precisely through the acceptance of impermanence one achieves… eternity. For although the wood ages, the ritual endures, and the divine presence never wanes. Each reconstruction is a purification: the shrine returns to its pristine freshness, as if time held no sway over it. It is a little like zen: instead of resisting impermanence, one reveres it and transforms it into a source of continuity.

The symbolism of the entire ritual is profoundly Japanese. On the one hand, there is the idea of mujo (無常), the impermanence of all things. Even the most sacred shrine, built from the finest hinoki cypress, ages and decays. On the other hand, precisely through the acceptance of impermanence one achieves… eternity. For although the wood ages, the ritual endures, and the divine presence never wanes. Each reconstruction is a purification: the shrine returns to its pristine freshness, as if time held no sway over it. It is a little like zen: instead of resisting impermanence, one reveres it and transforms it into a source of continuity.

But it is not merely a matter of philosophy – it is also a colossal architectural undertaking. The buildings are erected on the adjacent parcel, reproducing even the tiniest details of the ancient shinmei-zukuri style. What is more, not only the shrines themselves are renewed. The sacred treasures (shintai), vestments, ritual tools, and even bridges and fences are replaced. More than thirty different ceremonies accompany the entire process, during which not only material objects are reborn, but also rituals, songs, kagura dances, and artisanal skills. It is a grand test for Japan’s master carpenters and craftsmen – there are no architectural blueprints, knowledge is passed orally and through practice, from master to apprentice.

But it is not merely a matter of philosophy – it is also a colossal architectural undertaking. The buildings are erected on the adjacent parcel, reproducing even the tiniest details of the ancient shinmei-zukuri style. What is more, not only the shrines themselves are renewed. The sacred treasures (shintai), vestments, ritual tools, and even bridges and fences are replaced. More than thirty different ceremonies accompany the entire process, during which not only material objects are reborn, but also rituals, songs, kagura dances, and artisanal skills. It is a grand test for Japan’s master carpenters and craftsmen – there are no architectural blueprints, knowledge is passed orally and through practice, from master to apprentice.

Ritual and Practice – What does Sengū look like in detail?

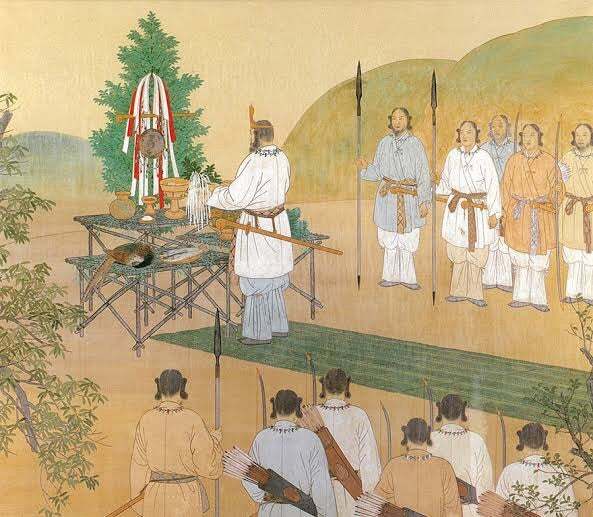

When the time for Shikinen Sengū arrives, the whole of Ise begins to breathe to a different rhythm. Over years of preparation, timber is brought in, new sacred treasures (shinpō, 神宝) are forged, the kagura dance is rehearsed – but the culmination of everything is Sengyo-no-gi (遷御の儀), the nocturnal ceremony of transferring the divine object of worship to the new shrine. In the case of Naikū, this is the sacred mirror Yata-no-Kagami, the symbol of the goddess Amaterasu. In absolute silence, by torchlight and the sound of drums, a procession of priests carries the gleaming object, wrapped in white cloth, from the former shrine to the newly constructed one standing just a few meters away. The atmosphere is heavy with solemnity – no photographs, no outside spectators. It is the moment when divinity “moves” into its fresh dwelling. It is said that in the forest of Ise at night one can sense a subtle change in the air.

When the time for Shikinen Sengū arrives, the whole of Ise begins to breathe to a different rhythm. Over years of preparation, timber is brought in, new sacred treasures (shinpō, 神宝) are forged, the kagura dance is rehearsed – but the culmination of everything is Sengyo-no-gi (遷御の儀), the nocturnal ceremony of transferring the divine object of worship to the new shrine. In the case of Naikū, this is the sacred mirror Yata-no-Kagami, the symbol of the goddess Amaterasu. In absolute silence, by torchlight and the sound of drums, a procession of priests carries the gleaming object, wrapped in white cloth, from the former shrine to the newly constructed one standing just a few meters away. The atmosphere is heavy with solemnity – no photographs, no outside spectators. It is the moment when divinity “moves” into its fresh dwelling. It is said that in the forest of Ise at night one can sense a subtle change in the air.

The ceremony of Sengū is not the work of individuals, but of the entire community. The Shintō priests have their clearly defined roles. The daigūji (大宮司), the high priest of Ise (currently from the Takatsukasa family, related to the imperial line), presides over the rituals. Beside him stand hundreds of others – from young assistants to seasoned masters of ancient songs and dances. Many of the rituals are duties performed “on behalf of” the emperor, for he, as a descendant of Amaterasu, is the true master of the sanctuary. In history, members of the imperial family – especially women – often served as the highest priestesses (saio) of Ise, and even today imperial daughters take part in key ceremonies.

The ceremony of Sengū is not the work of individuals, but of the entire community. The Shintō priests have their clearly defined roles. The daigūji (大宮司), the high priest of Ise (currently from the Takatsukasa family, related to the imperial line), presides over the rituals. Beside him stand hundreds of others – from young assistants to seasoned masters of ancient songs and dances. Many of the rituals are duties performed “on behalf of” the emperor, for he, as a descendant of Amaterasu, is the true master of the sanctuary. In history, members of the imperial family – especially women – often served as the highest priestesses (saio) of Ise, and even today imperial daughters take part in key ceremonies.

It is not, however, merely a matter of offering prayers. The priests undergo Kessai (潔斎), a ritual purification of body and spirit, as well as Sanro (参籠) – seclusion in a special building called Saikan. There they live under austere conditions, dressed in white kimono and hakama, cut off from the outside world. They eat only meals prepared within the Saikan, avoiding all “contaminations” of the everyday world. This practice may last from two nights for smaller ceremonies, up to five nights for the most important rituals – such as Sengyo-no-gi. One priest once compared it to the mental training of an athlete before a competition: sitting in silence, cutting off distracting thoughts, entering a state of absolute concentration.

It is not, however, merely a matter of offering prayers. The priests undergo Kessai (潔斎), a ritual purification of body and spirit, as well as Sanro (参籠) – seclusion in a special building called Saikan. There they live under austere conditions, dressed in white kimono and hakama, cut off from the outside world. They eat only meals prepared within the Saikan, avoiding all “contaminations” of the everyday world. This practice may last from two nights for smaller ceremonies, up to five nights for the most important rituals – such as Sengyo-no-gi. One priest once compared it to the mental training of an athlete before a competition: sitting in silence, cutting off distracting thoughts, entering a state of absolute concentration.

It is worth remembering that Shikinen Sengū is not only a single evening, but a great sequence of rituals stretching over years. Officially, more than thirty major ceremonies are associated with it, and in practice – hundreds of accompanying events. Every transport of timber, every procession, every laying of stones for the foundations has its own ritual. Added to this is the involvement of the entire community: miyadaiku carpenters, masters weaving the sacred shimenawa ropes, gagaku musicians, as well as the residents of Ise, who take part in processions carrying wood and stones.

It is worth remembering that Shikinen Sengū is not only a single evening, but a great sequence of rituals stretching over years. Officially, more than thirty major ceremonies are associated with it, and in practice – hundreds of accompanying events. Every transport of timber, every procession, every laying of stones for the foundations has its own ritual. Added to this is the involvement of the entire community: miyadaiku carpenters, masters weaving the sacred shimenawa ropes, gagaku musicians, as well as the residents of Ise, who take part in processions carrying wood and stones.

The scale of the endeavor is immense – it is estimated that during a single Shikinen Sengū cycle several thousand people are directly involved, and indirectly – hundreds of thousands of donors and pilgrims from all over Japan. In 2013, at the 62nd reconstruction, more than 14 million pilgrims came to Ise. For many, it was not only a religious act, but also an experience of national culture: to witness Japan reborn in a rhythm that has continued for thirteen centuries.

Materials, Nature, and Eternity

One cannot speak of Shikinen Sengū without speaking of wood. But not just any wood – it is hinoki (檜 / 桧), the Japanese cypress, known in Japan as the “roof of the gods.” Its timber is light, durable, resistant to moisture and insects, and carries a fragrance that, even after years, can still fill interiors with freshness (see more here: The Japanese Art of Fragrance in the Warrior Life and Death of the Samurai). Since ancient times, hinoki has been reserved for the most sacred buildings – from Ise Jingū to the tombs of emperors. In traditional Japanese thought, wood is not a dead material but a living substance that in itself has the power to purify and renew space.

One cannot speak of Shikinen Sengū without speaking of wood. But not just any wood – it is hinoki (檜 / 桧), the Japanese cypress, known in Japan as the “roof of the gods.” Its timber is light, durable, resistant to moisture and insects, and carries a fragrance that, even after years, can still fill interiors with freshness (see more here: The Japanese Art of Fragrance in the Warrior Life and Death of the Samurai). Since ancient times, hinoki has been reserved for the most sacred buildings – from Ise Jingū to the tombs of emperors. In traditional Japanese thought, wood is not a dead material but a living substance that in itself has the power to purify and renew space.

The history of sourcing hinoki for rebuilding Ise, however, shows that even a divine forest can be mortal. At first, cypresses were simply cut down around the sanctuary, but already in the Kamakura period, trees of sufficient thickness were lacking. In the Edo period, timber began to be brought in from the Kiso mountains in Nagano Prefecture – an area still renowned today for the finest cypresses in the country. And what of Ise itself? One need only look at old photographs from the beginning of the Meiji era to be astonished – the mountains around the Isuzu River were then almost bare. The reason? Millions of pilgrims during the so-called okage mairi warmed themselves and cooked their meals, consuming firewood from the surrounding forests in amounts that exceeded nature’s capacity.

The history of sourcing hinoki for rebuilding Ise, however, shows that even a divine forest can be mortal. At first, cypresses were simply cut down around the sanctuary, but already in the Kamakura period, trees of sufficient thickness were lacking. In the Edo period, timber began to be brought in from the Kiso mountains in Nagano Prefecture – an area still renowned today for the finest cypresses in the country. And what of Ise itself? One need only look at old photographs from the beginning of the Meiji era to be astonished – the mountains around the Isuzu River were then almost bare. The reason? Millions of pilgrims during the so-called okage mairi warmed themselves and cooked their meals, consuming firewood from the surrounding forests in amounts that exceeded nature’s capacity.

It was only in the Taishō period (the 1920s) that a 200-year plan for the renewal of Ise’s forests was drawn up. Professors and foresters devised a project of systematic cypress planting so that, over two centuries, the sanctuary would be self-sufficient in building materials. On land covering 5,500 hectares – the size of Tokyo’s entire Setagaya ward – a vast reforestation effort was undertaken. The results can be seen today: the trees have already reached diameters of several dozen centimeters, and for the first time in more than 700 years some of them could be used in the most recent Sengū in 2013.

It was only in the Taishō period (the 1920s) that a 200-year plan for the renewal of Ise’s forests was drawn up. Professors and foresters devised a project of systematic cypress planting so that, over two centuries, the sanctuary would be self-sufficient in building materials. On land covering 5,500 hectares – the size of Tokyo’s entire Setagaya ward – a vast reforestation effort was undertaken. The results can be seen today: the trees have already reached diameters of several dozen centimeters, and for the first time in more than 700 years some of them could be used in the most recent Sengū in 2013.

The sacred structures of Ise do not exist in a vacuum – they form a harmonious whole with the surrounding nature. Most important here is the Isuzu River, whose waters flow at the foot of the Naikū sanctuary. Every pilgrim, before entering, undergoes the ritual of misogi – symbolic purification in the cool water, to cross the boundary between the everyday world and the realm of the sacred. The forests surrounding the shrine are called the “Sacred Grove” (Jingū-rin, 神宮林). In the thicket grow not only cypresses but also ancient sugi (Japanese cryptomeria), camphor trees, and oaks, creating an atmosphere that is almost mystical – as if time itself had stopped.

Importantly, Shikinen Sengū is not merely a tradition looking backward, but also a modern laboratory of ecology. Today, great emphasis is placed on sustainable resource management: every tree felled has its “successor” in the form of a young sapling. Over 10,000 trees are planted here annually, and at the planting ceremony not only foresters but also priests in white robes participate, treating the act as a religious ritual (in Japanese culture, trees have always been close to people and to the sacred – see more here: A Profound Bond Between Humans and Trees in Japanese Culture and Ukiyo-e Art). Likewise, the elements of the old shrine are never wasted – planks and beams are distributed to other shrines across Japan, renewing torii, bridges, and smaller structures. It is a kind of reincarnation of wood – nothing ends, everything passes into a new form.

Importantly, Shikinen Sengū is not merely a tradition looking backward, but also a modern laboratory of ecology. Today, great emphasis is placed on sustainable resource management: every tree felled has its “successor” in the form of a young sapling. Over 10,000 trees are planted here annually, and at the planting ceremony not only foresters but also priests in white robes participate, treating the act as a religious ritual (in Japanese culture, trees have always been close to people and to the sacred – see more here: A Profound Bond Between Humans and Trees in Japanese Culture and Ukiyo-e Art). Likewise, the elements of the old shrine are never wasted – planks and beams are distributed to other shrines across Japan, renewing torii, bridges, and smaller structures. It is a kind of reincarnation of wood – nothing ends, everything passes into a new form.

What is Sengū for the People?

The history of Shikinen Sengū is not only a religious ritual – it is also a mirror of Japan’s history, reflecting wars, peace, and social transformations. The tradition that began in the 7th century had its dark moments: in the Sengoku period – times of fratricidal wars and constant chaos (more about this here: The Real Sengoku – What Was Life Like for the Swordless in the Shadow of Samurai Wars?) – the cycle of renewal was suspended multiple times. In the archives we find records that reconstructions scheduled for the 15th and 16th centuries did not take place due to lack of funds, timber, and political stability. Ise – though spiritually central – had to yield to the more earthly logic of war. This also shows how deeply Shintō and political power were intertwined: when the social order collapsed, so too did the rituals fall silent.

The history of Shikinen Sengū is not only a religious ritual – it is also a mirror of Japan’s history, reflecting wars, peace, and social transformations. The tradition that began in the 7th century had its dark moments: in the Sengoku period – times of fratricidal wars and constant chaos (more about this here: The Real Sengoku – What Was Life Like for the Swordless in the Shadow of Samurai Wars?) – the cycle of renewal was suspended multiple times. In the archives we find records that reconstructions scheduled for the 15th and 16th centuries did not take place due to lack of funds, timber, and political stability. Ise – though spiritually central – had to yield to the more earthly logic of war. This also shows how deeply Shintō and political power were intertwined: when the social order collapsed, so too did the rituals fall silent.

The revival came in the Edo period, and with great flourish. Japan, closed off from the outside world, found in pilgrimages to Ise a spiritual outlet. The phenomenon was called okage mairi, the “pilgrimage by the gods’ grace.” In 1705, according to chronicles, more than 3.6 million pilgrims came to Ise in a single year – nearly one-quarter of Japan’s entire population! Interestingly, many of them were ordinary peasants and townsfolk who, without their lords’ permission, abandoned work and set out on the journey. For it was believed that if the heart was stirred by the gods, one could not refuse. There are accounts of children and animals that “on their own” made their way toward Ise, regarded as signs of divine calling. Over time, an affectionate name for the sanctuary entered common usage: O-ise-san – as if Ise were a close, venerable person, a friend of the nation.

The revival came in the Edo period, and with great flourish. Japan, closed off from the outside world, found in pilgrimages to Ise a spiritual outlet. The phenomenon was called okage mairi, the “pilgrimage by the gods’ grace.” In 1705, according to chronicles, more than 3.6 million pilgrims came to Ise in a single year – nearly one-quarter of Japan’s entire population! Interestingly, many of them were ordinary peasants and townsfolk who, without their lords’ permission, abandoned work and set out on the journey. For it was believed that if the heart was stirred by the gods, one could not refuse. There are accounts of children and animals that “on their own” made their way toward Ise, regarded as signs of divine calling. Over time, an affectionate name for the sanctuary entered common usage: O-ise-san – as if Ise were a close, venerable person, a friend of the nation.

In the Edo period, a pilgrimage to Ise was something like Japan’s first form of mass tourism. Inns, lodgings, rest stops, entire villages and towns lived off the ceaseless stream of worshippers. One could say that Sengū and the associated “pilgrimage booms” also built the country’s social and economic infrastructure. In many households to this day, mementos are preserved from grandparents and great-grandparents who “made it to O-ise-san.”

In the Edo period, a pilgrimage to Ise was something like Japan’s first form of mass tourism. Inns, lodgings, rest stops, entire villages and towns lived off the ceaseless stream of worshippers. One could say that Sengū and the associated “pilgrimage booms” also built the country’s social and economic infrastructure. In many households to this day, mementos are preserved from grandparents and great-grandparents who “made it to O-ise-san.”

And in the present? Though the world has changed, Ise Jingū still draws millions. During the last Sengū in 2013, the number of visitors reached 14 million, and throughout the year about 8 million pilgrims and tourists pass through Naikū and Gekū. For the older generation, visiting Ise remains a life obligation, while for the younger it is increasingly becoming a form of spiritual tourism. It is not only about religion: it is also contact with history, with nature, and even a fashionable “reset” from life in the metropolis. On social media, young Japanese eagerly share photos from Uji Bridge, purification rituals in the Isuzu River, or simply the atmosphere of Ise’s forests, aligning with the global trend of seeking authenticity.

And in the present? Though the world has changed, Ise Jingū still draws millions. During the last Sengū in 2013, the number of visitors reached 14 million, and throughout the year about 8 million pilgrims and tourists pass through Naikū and Gekū. For the older generation, visiting Ise remains a life obligation, while for the younger it is increasingly becoming a form of spiritual tourism. It is not only about religion: it is also contact with history, with nature, and even a fashionable “reset” from life in the metropolis. On social media, young Japanese eagerly share photos from Uji Bridge, purification rituals in the Isuzu River, or simply the atmosphere of Ise’s forests, aligning with the global trend of seeking authenticity.

The significance of Ise has also extended beyond Japan. In 2016, during the G7 summit in Shima, world leaders – from Barack Obama to Angela Merkel – visited Ise Jingū together with Prime Minister Shinzō Abe. It was not only a diplomatic gesture but also a symbolic one – presenting Japan not through Tokyo’s modern skyscrapers or technology, but through its spiritual heart, rooted in cyclical renewal and communion with nature. The world saw that in times of crises and transformations, Japan prefers to return to what seems unchanging – and what, in truth, endures precisely because it is always changing.

The significance of Ise has also extended beyond Japan. In 2016, during the G7 summit in Shima, world leaders – from Barack Obama to Angela Merkel – visited Ise Jingū together with Prime Minister Shinzō Abe. It was not only a diplomatic gesture but also a symbolic one – presenting Japan not through Tokyo’s modern skyscrapers or technology, but through its spiritual heart, rooted in cyclical renewal and communion with nature. The world saw that in times of crises and transformations, Japan prefers to return to what seems unchanging – and what, in truth, endures precisely because it is always changing.

The Philosophy of Renewal and the Meaning of Shikinen Sengū

At first glance, the idea of demolishing and rebuilding a shrine every two decades sounds like a paradox—or even folly. Why destroy something that could stand for centuries? Yet within this logic, rooted in Shintō and the Buddhist notion of mujo (無常—impermanence), it is precisely transience that lends things their durability. The structure itself is not eternal, but its rebirth is— a cycle that, like the seasons, returns, repeats, and thereby becomes timeless. At Ise Jingū, eternity does not dwell in stone, but in the rhythm of wood, which every twenty years returns to its primordial form.

At first glance, the idea of demolishing and rebuilding a shrine every two decades sounds like a paradox—or even folly. Why destroy something that could stand for centuries? Yet within this logic, rooted in Shintō and the Buddhist notion of mujo (無常—impermanence), it is precisely transience that lends things their durability. The structure itself is not eternal, but its rebirth is— a cycle that, like the seasons, returns, repeats, and thereby becomes timeless. At Ise Jingū, eternity does not dwell in stone, but in the rhythm of wood, which every twenty years returns to its primordial form.

Shintō has no great scriptures or systematic doctrines—it is a religion of gestures, rituals, and the human relationship with nature. That is why Shikinen Sengū is not only an engineering project, but a daily lesson in how the sacred permeates the profane. The Uji Bridge, which a pilgrim crosses before entering Naikū, is not merely a construction—it is a boundary between the everyday world and the holy. Likewise, ablution in the Isuzu River is not hygiene, but a symbolic return to purity, to the zero point. Every element of Sengū—from the purification of stones to the transfer of Amaterasu’s mirror—emphasizes that the sacred does not exist apart from life; it sets life’s rhythm and lends it meaning.

One can also view Sengū through the lens of a principle the Japanese, in the world of work, would call 頑張る (ganbaru)—“to persevere and give one’s all.” It is the striving for perfection in what can be renewed, coupled with the acceptance that nothing will be everlasting. The shrine is identical in form, yet the wood, the carpenters’ hands, the social context—everything is different. Fidelity here does not consist in preserving the same building, but in safeguarding the essence—the style, the proportions, the ritual. It is precisely the flexibility toward change combined with the invariance of the core that has allowed Ise Jingū to remain itself for thirteen centuries.

One can also view Sengū through the lens of a principle the Japanese, in the world of work, would call 頑張る (ganbaru)—“to persevere and give one’s all.” It is the striving for perfection in what can be renewed, coupled with the acceptance that nothing will be everlasting. The shrine is identical in form, yet the wood, the carpenters’ hands, the social context—everything is different. Fidelity here does not consist in preserving the same building, but in safeguarding the essence—the style, the proportions, the ritual. It is precisely the flexibility toward change combined with the invariance of the core that has allowed Ise Jingū to remain itself for thirteen centuries.

What does this tell us today, in an age of steel-and-glass skyscrapers? Perhaps that our obsession with “permanence” is an illusion. In a world where change has become the only constant, Shikinen Sengū offers another perspective: the point is not to stop time, but to be able to re-create it in a rhythm that gives it meaning. This is why Ise fascinates even those outside Japan—from philosophers and architects to politicians who, upon visiting the sanctuary, seek something more than colorful folklore.

For the Japanese, Shikinen Sengū remains a point of reference—not so much a religious duty as a metaphor for life. It means that one can let things go so that they may return. That true continuity does not lie in stubborn resistance to transformation, but in consciously incorporating change into the cycle. In times when the world accelerates and everything seems to erode—traditions, communities, relationships—the ceremony at Ise teaches that renewal is not a loss, but an opportunity. It is a lesson in humility before time and, at once, a call to courage: not to fear demolition if it makes renewal possible.

For the Japanese, Shikinen Sengū remains a point of reference—not so much a religious duty as a metaphor for life. It means that one can let things go so that they may return. That true continuity does not lie in stubborn resistance to transformation, but in consciously incorporating change into the cycle. In times when the world accelerates and everything seems to erode—traditions, communities, relationships—the ceremony at Ise teaches that renewal is not a loss, but an opportunity. It is a lesson in humility before time and, at once, a call to courage: not to fear demolition if it makes renewal possible.

Eternity in Twenty-Year Measures

The observances of Shikinen Sengū are not a single day, but an entire cycle of festivals and rituals stretching over years. The most spectacular moments, however, cluster around the reconstruction itself and the transfer of the divine regalia. Residents of Ise and the surrounding area take part in processions during which enormous hinoki cypress logs are floated down the Isuzu River and then hauled through the streets—to the accompaniment of drums, songs, and joyful shouts. Thousands gather to see how material that has ripened in water and sunlight for a decade becomes the body of the new shrine.

The observances of Shikinen Sengū are not a single day, but an entire cycle of festivals and rituals stretching over years. The most spectacular moments, however, cluster around the reconstruction itself and the transfer of the divine regalia. Residents of Ise and the surrounding area take part in processions during which enormous hinoki cypress logs are floated down the Isuzu River and then hauled through the streets—to the accompaniment of drums, songs, and joyful shouts. Thousands gather to see how material that has ripened in water and sunlight for a decade becomes the body of the new shrine.

For the people of Ise, Sengū is a celebration of the entire community. Craft workshops run at full tilt, schools organize educational ceremonies, and pilgrims from across the country arrive to witness this moment of renewal at least once in their lives.

And here the question arises: what next? In the 25th century, in the year 2413, will the Japanese still be demolishing and rebuilding their sanctuary every twenty years? Judging by the persistence, patience, and love of continuity that characterize this nation, one might suppose they will. That even if the world is dominated by glass cities and digital temples in virtual reality, a modest wooden structure will still stand in the forest by the Isuzu-gawa—always new, always old.

And here the question arises: what next? In the 25th century, in the year 2413, will the Japanese still be demolishing and rebuilding their sanctuary every twenty years? Judging by the persistence, patience, and love of continuity that characterize this nation, one might suppose they will. That even if the world is dominated by glass cities and digital temples in virtual reality, a modest wooden structure will still stand in the forest by the Isuzu-gawa—always new, always old.

Shikinen Sengū shows that eternity does not consist in the endurance of matter, but in rhythm, repetition, and the conscious assent to impermanence. Every twenty years Japan offers us a lesson that is hard to overlook: for something to truly exist, it must be able to be reborn. And perhaps for this very reason, if humanity endures (and Japan with it), then among the ruins of future empires and technologies, O-ise-san—the nation’s friend—will still rise from the ashes, to remind the world every twenty years that renewal is the oldest and surest form of eternity.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Wild Ride of Japan's Onbashira – A Deadly Festival of Courage, Madness, and Profound Spirituality

Shinto Priestess Miko – From Powerful Shaman to Part-Time Work

Return to Hyrule: Shinto Mythology of Japan in The Legend of Zelda

Japanese Folklore in Shin Megami Tensei: Playing Persona in the Rhythms of Shinto

Goddess Uzume dances naked and, with her sacred antics, saves us from sorrowful seriousness – Japanese mythology, how timely today