Japanese Art of Silence – How the Concept of Silence Can Highlight Cultural Differences

How We Perceive Silence

The approach to silence (and emptiness) is likely one of the most fundamental differences between Western and Japanese cultures. In this article, we will delve into these contrasts, exploring the philosophical and spiritual roots of silence in Japan, its role in daily life, and how it has been described by poets. We will also attempt to find the universal values of silence that can unite both cultures, turning it into a source of harmony and solace in everyday life.

Silence as a Form of Communication

Remaining silent is one of the behavioral elements that differ significantly between Japanese and Western cultures—and it is often a source of misunderstandings. For example, silence in response to a question, particularly in formal settings, is in Japan a sign of humility and deep reflection. Through silence, one demonstrates respect for the speaker and the seriousness of their words, refraining from giving a hasty response without careful consideration (even if one already knows the answer). This culture values thoughtfulness and discourages impulsive answers, which might appear shallow or unconsidered. Silence thus becomes a way to show respect for the speaker, indicating that their words are being carefully pondered.

Japanese proverbs, such as kuchi wa wazawai no moto (口は災いの元, “The mouth is the source of calamities”) or mokuzen no shitei (黙然の師弟, “The silent student and teacher”), reflect the belief that speaking can be harmful, whereas silence fosters deeper understanding. The Western adage “speech is silver, but silence is golden” holds an additional dimension in Japan—silence is a space where authenticity is born, and hasty words can disrupt it.

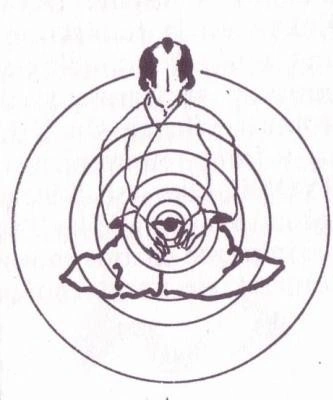

Haragei (腹芸): The "Art of the Belly"

In Japanese thought, the belly (hara, 腹) symbolizes the center of emotions and inner truth (similar to the heart in Western thinking). Silence and the ability to interpret the unspoken are essential in haragei, as they allow emotions and intentions to be conveyed nonverbally yet profoundly understood. This form of communication is especially prominent in master-student relationships in traditional arts, where understanding arises not from explanations but through shared silence and experience.

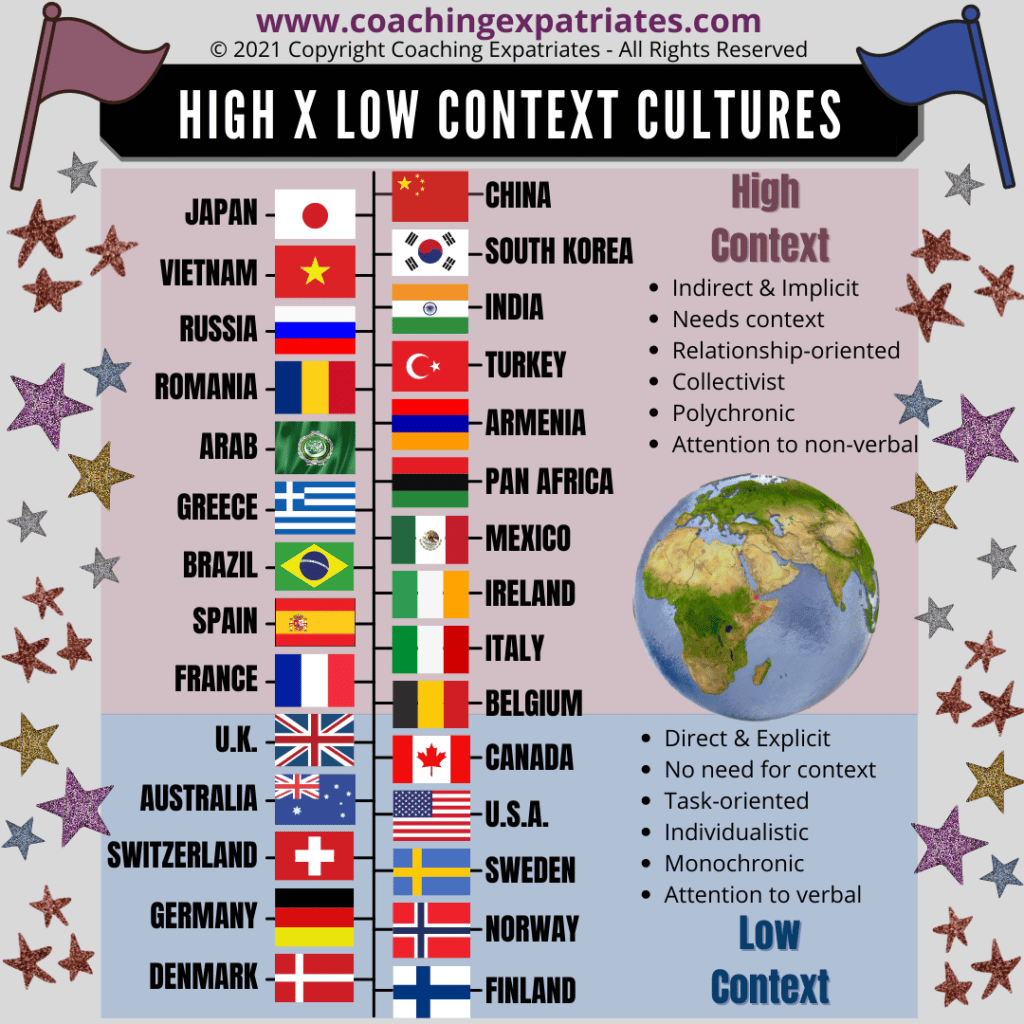

High- and Low-Context Cultures

Low-context cultures, characteristic of Western countries like the United States, Germany, or Sweden (as well as Poland, though to a slightly lesser degree), prioritize clarity and directness in communication. In such cultures, the meaning of a message is almost entirely contained in the words themselves. For example, a manager in a low-context culture might say: “The report needs to be ready by 3:00 PM tomorrow.” This statement is straightforward, leaves no room for misinterpretation, and does not require contextual knowledge.

Silence in Japan: The Art of Subtlety

Silence is a crucial tool for avoiding conflict and an expression of respect and politeness. For example, in the workplace, when a subordinate remains silent after hearing their manager’s suggestion, it does not signify a lack of engagement but rather reflection and consideration of what has been said. In family and social relationships, silence creates space to avoid unnecessary words that could disturb harmony. A key concept in such situations is sasshi (察し), the ability to intuitively grasp unspoken intentions. Let’s explore some striking examples of silence in Japanese culture and daily life.

The Tea Ceremony (sadō)

The Tea Ceremony (sadō)

In the Japanese tea ceremony, silence is as important as the precise movements of the host. It allows participants to focus entirely on the present moment and appreciate the harmony of the surroundings. The absence of words is not an emptiness—it is a space brimming with attention, respect, and beauty. Silence is virtually the most important and indispensable element of the ceremony.

Resolving Conflicts and Saying “No”

In Japan (and Korea), “no” is often expressed through silence or ambiguous phrases like “That might be difficult.” This method of refusal avoids direct confrontation and preserves harmony in relationships. A more explicit example would be an employee saying to their manager, “Yes, I’m thinking about how to accomplish this and considering whether I might need help mitigating the potential losses if the task isn’t carried out correctly,” instead of directly stating, “I won’t follow this order because it could lead to losses.”

Silence in Negotiations and Business

In business, silence is also a sign of respect for the speaker—listening quietly demonstrates full attention and engagement with what the other person is trying to convey. In this way, silence becomes a tool for building trust and relationships, rather than being perceived as an empty void, as it often is in low-context cultures.

Silence as a form of communication in Japan is a delicate art that requires sensitivity and openness to master. It allows relationships to be built harmoniously, based on respect and understanding. It serves as a reminder that sometimes, what we don’t say expresses more than words.

Silence in Everyday Life

Silence During Meals and Travel

Many tourists are surprised by the extraordinary quietness at crowded airports, in subway stations, or on buses in Japan. Public travel in Japan is another moment of silence that can astonish visitors. In crowded shinkansen carriages, passengers travel in silence, reading books, gazing out at the changing scenery, or simply closing their eyes. Talking on the phone is prohibited, and speaking loudly is considered impolite. This collective silence creates a space for contemplation and rest.

Silence Among Loved Ones: A Sign of Understanding

Families often spend time together in silence, engaged in their own thoughts or simple activities like brewing tea or arranging flowers in the style of ikebana. Shared silence, rather than creating distance, becomes a bond that strengthens relationships.

Ishin-denshin (Heart-to-heart communication)

The concept of ishin-denshin (以心伝心), which literally translates to "heart-to-heart communication," refers to the ability to sense the emotions and thoughts of others without the need for spoken words. It is the skill of interpreting subtle signals, gestures, and atmospheres that Western observers often overlook. In a society where group harmony holds significant importance, ishin-denshin allows for the avoidance of conflict and the maintenance of delicate social relationships. This form of silent dialogue is both elegant and far safer than an open verbal dispute.

Shinrin-yoku (Forest Bathing): Soul Renewal in Nature's Embrace

Studies have shown that this practice reduces stress levels, improves concentration, and calms the mind. For the Japanese, however, it is something more—it is a return to harmony with nature. While Western tourists often associate forests with activity, in Japan, forests are spaces for introspection and spiritual healing.

The Role of Silence in Education

Parents teach their children that words hold weight, but an excess of them can be harmful. An example is the repetition of the proverb kuchi wa wazawai no moto ("the mouth is the source of calamity"), encouraging children to think carefully before speaking. Silence becomes a way to instill patience, respect, and focus.

Silence in Japanese Philosophy

Silence in Meditation

Zen, as a school of Buddhism, has made silence one of the primary tools for achieving enlightenment. The practice of zazen (座禅) is simply sitting in silence—a practice that allows one to calm the mind and delve into its deeper layers. In zazen, silence is not only the surrounding environment but also the goal—the attainment of inner peace where wandering thoughts cease, and one becomes fully present in the moment.

Ma (間): Silence as the Rhythm of Life

In traditional Japanese music, such as gagaku, the ma of silence is as important as the sound—it is where harmony is born. In Zen architecture, gardens filled with empty spaces and harmoniously arranged stones teach that the void defines what exists. Similarly, in everyday life, silence gives meaning to actions, and a pause in conversation provides room for reflection.

Silence as a Connection to the Sacred

In Buddhist and Shinto shrines, silence becomes a means of connecting with the sacred. In Zen temples, absolute silence prevails. In Shinto rituals, priests perform ceremonies in silence, leaving space for the gods (kami) to reveal their presence.

The tea ceremony (chanoyu) is another ritual of silence, where every action is celebrated with full awareness of the present moment. The sound of water, the delicate tap of a bamboo ladle on the edge of a tea bowl, or the rustle of a kimono are elements of harmony that silence helps to emphasize. As the principle of wabi-sabi teaches, beauty lies in simplicity and imperfection—and silence is an inseparable part of both.

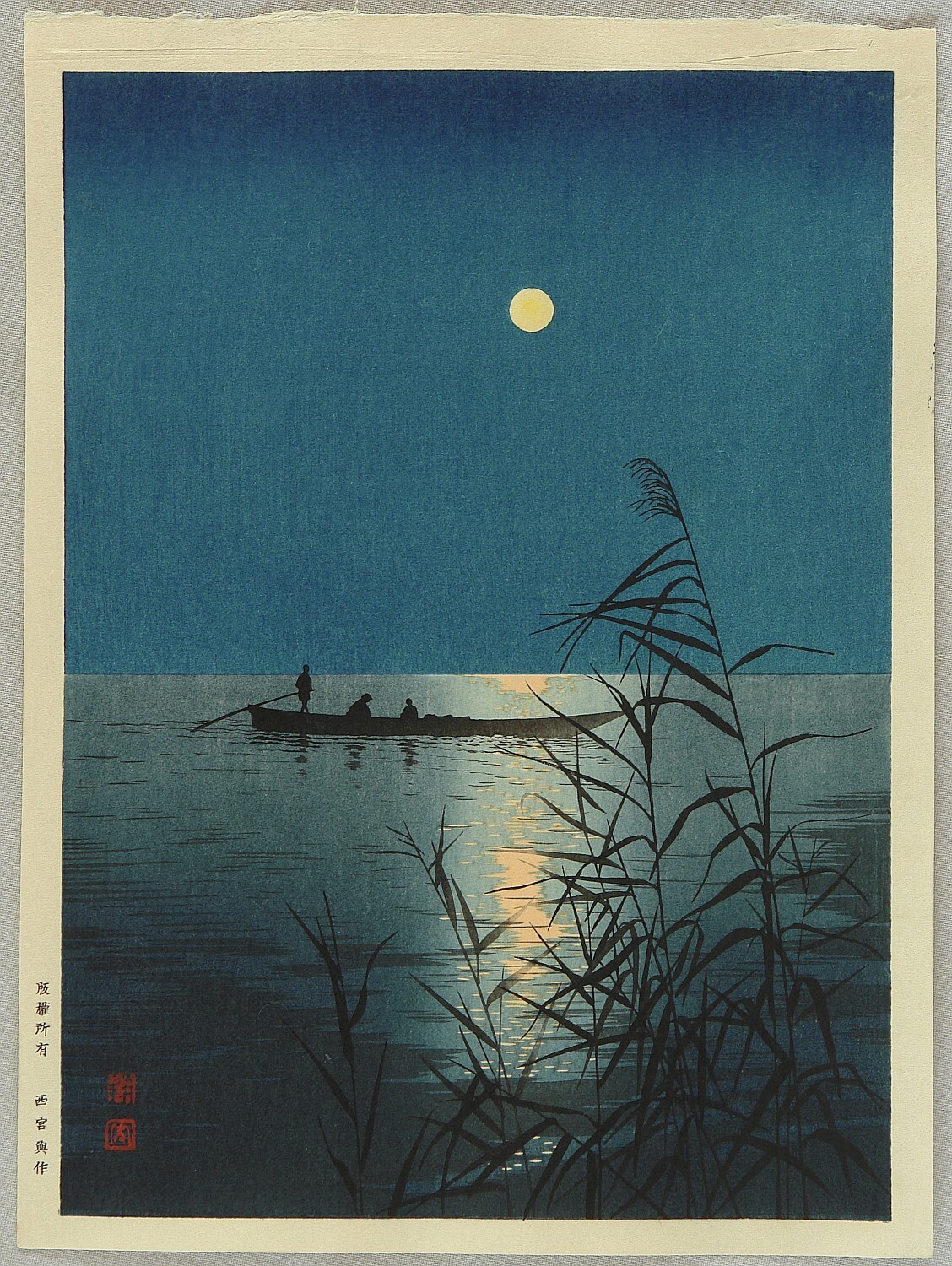

Silence in Japanese Poetry

Japanese literature, particularly poetry, has celebrated silence for centuries as a space for reflection and contemplation. Haiku and waka poems are essentially built on silence, understood here as what is unspoken. Silence in these works is both the protagonist and the backdrop—a space that allows words to resonate in the reader’s imagination.

***

閑さや岩にしみ入る蝉の声

(Shizukesa ya iwa ni shimiiru semi no koe)

“Profound silence—

the cicadas’ song seeps

into the cracks of the rocks.”

– Bashō Matsuo, 1689, Oku no Hosomichi (The Narrow Road to the Interior)

In this haiku, silence is not an absence of sound but a space that accentuates the fleeting sounds of nature. The song of the cicadas, a symbol of the passing summer and the inexorable flow of time—and life—penetrates the rocks, an image metaphorically pointing to harmony between the transient and the eternal. Bashō creates a poetic contrast where the sounds of nature merge with the silence of eternity, inviting the reader to reflect on impermanence.

This haiku teaches that silence is not empty—it is a space where sounds, thoughts, and emotions find their true meaning. Through silence, we hear the cicadas' song, which, when accentuated in this way, allows us to see life from a distance and contemplate its fleeting nature.

***

秋風にたなびく雲の絶え間より

(akikaze ni tanabiku kumo no taema yori)

"Autumn wind—

between drifting clouds,

a glimpse of sky."

– Fujiwara no Teika, 13th century, Shin Kokin Wakashū

In this poem, silence (or emptiness) resides in the gap between the clouds, where the brightness of the sky becomes a metaphor for moments of reflection amidst the chaos of daily life. The autumn wind, carrying the clouds, symbolizes transience, while the break in their veil reminds us of fleeting tranquility, always accessible if we look for it.

Teika, a master of waka poetry, illustrates how silence—like the gap in the clouds—can appear suddenly, bringing solace and profound contemplation. It is a moment of immersion in one's inner world, allowing a fuller experience of reality.

***

心なき身にもあはれは知られけり

(kokoro naki mi ni mo aware wa shirarekeri)

"Without a heart,

I still feel sorrow

in autumn's silence."

– Saigyō Hōshi, 12th century, Sankashū

Saigyō, both a monk and a poet, finds a paradox in the silence of autumn. As a Buddhist monk, he has renounced worldly concerns, including emotions. Yet his "unfeeling" heart still perceives the melancholy of silence—a sorrow for what passes. This sorrow, a worldly sensation, simultaneously serves as a reminder that all earthly things are transient. Paradoxically, this awareness frees him from worldly worries and emotions.

This paradox demonstrates how silence provokes reflection. Japanese poetry teaches that silence is not emptiness but a space in which the beauty of fleeting moments, emotions, and contemplation resonate. As these poets reveal, it is in silence that we often hear the most—if we allow ourselves to pause and listen.

Conclusion

Ultimately, silence, no matter how it is interpreted, is a reminder of the importance of pausing in the rush of life. It is an invitation to listen to ourselves, to find harmony and peace in a noisy world. It is a universal gift that each of us can accept, discovering in it what we need most.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

Red Tears and Black Blood: The Modern Haiku of Ban’ya Natsuishi

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Tea Ceremony (sadō)

The Tea Ceremony (sadō)