Chimerical Masks of Noh Theatre – A Form Truer than Content

The Essence of Japan – the Most Foreign to Us

Carl Gustav Jung wrote about the persona – the social mask we wear to survive in the eyes of others. Beneath it lurks the shadow – everything unspoken. Western theatre aims for expression, catharsis, emotional eruption. Noh does the opposite – it condenses emotions, filters them through form, reduces them to their essence. Instead of stripping a person down, it dresses them in ritual. Instead of speaking – it suggests. Instead of acting – it waits. Like an echo that lingers long after everything has fallen silent. Noh masks do not express – they allow the viewer to feel what cannot be seen. This is not theatre to be understood. It is theatre that – if only we allow it to speak – begins to look at us.

What is noh? – A Voice from the Land of Yūgen

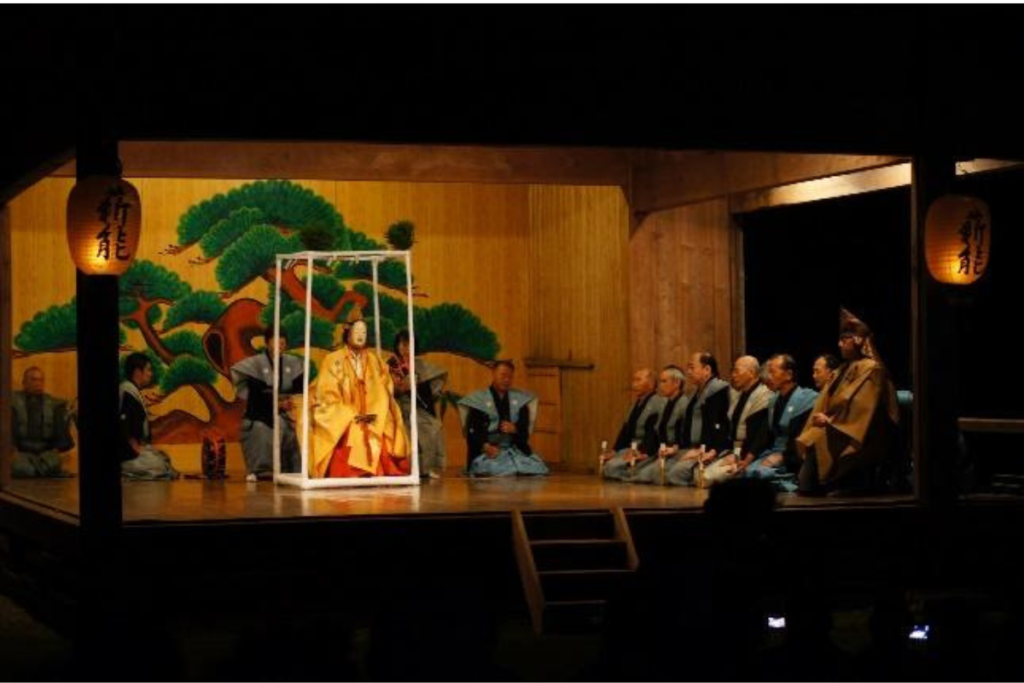

Noh theatre was born in 14th-century Japan, and its spiritual father was Zeami Motokiyo – an actor, playwright, and theorist whose treatises remain to this day a cornerstone not only of this art form, but of Japanese aesthetics in general. Noh emerged from earlier folk and religious performances, including dengaku and sarugaku, and absorbed the influences of Zen Buddhism and shintō rituals.

The central figure in noh is the shite – a character who typically represents a spirit or someone haunted by the ghosts of the past. Accompanying him is the waki, a person from the “present,” who provokes the story. The plot is often simple: a pilgrim meets a woman by a well. They talk. She disappears. In the second part, it is revealed she was a spirit. The end. But this simplicity is deceptive – for in noh theatre, the goal is not to tell a story, but to evoke a state of being that cannot be spoken. And here enters yūgen.

Yūgen – To See What Is Invisible

The noh stage is empty, ascetic. The set is limited to the image of a pine tree (kagami-ita) on the rear wall and a few props (yes, it is almost always a pine, regardless of the play). Every step, every turn, every gesture – is codified, ritualistic, deliberate. But it is in this rigidity that space for imagination is born. The mask does not express emotion, but creates the conditions to experience it. Movement does not describe, but evokes. The voice does not narrate – it resonates.

Differences Between Noh and European Theatre

In noh, everything works in reverse. The character does not develop – they are an archetype. Their feelings are eternal. There is no change – there is a cycle. No individualism – only universality. No conflict – only longing, transience, memory. Instead of action – a slow approach to a truth that will not be spoken at the end. Time does not flow – it thickens, suspends, rewinds, circles.

In noh theatre there is no haste. Silence has weight. Slowness is not the result of the form’s laziness, but of its density. Every gesture, pause, step – builds tension. Time is not a tool to “advance the plot,” but becomes an emotional structure in itself. Waiting, suspension, repetition – all this allows the viewer to go deeper, beyond words, beyond narration.

One could say that noh is not so much theatre to be watched, but theatre to be entered. Or a guided meditation. It is an experience that demands presence – not only from the actor, but from the viewer as well. And the mask that covers the shite’s face becomes at once a window – through which we do not look into the depths of the character, but into the depths of ourselves. For the mask in noh is the absolute key, the axis, the core. And today, we will get to know it more closely.

The Mask as a Threshold: Between Actor and Spirit

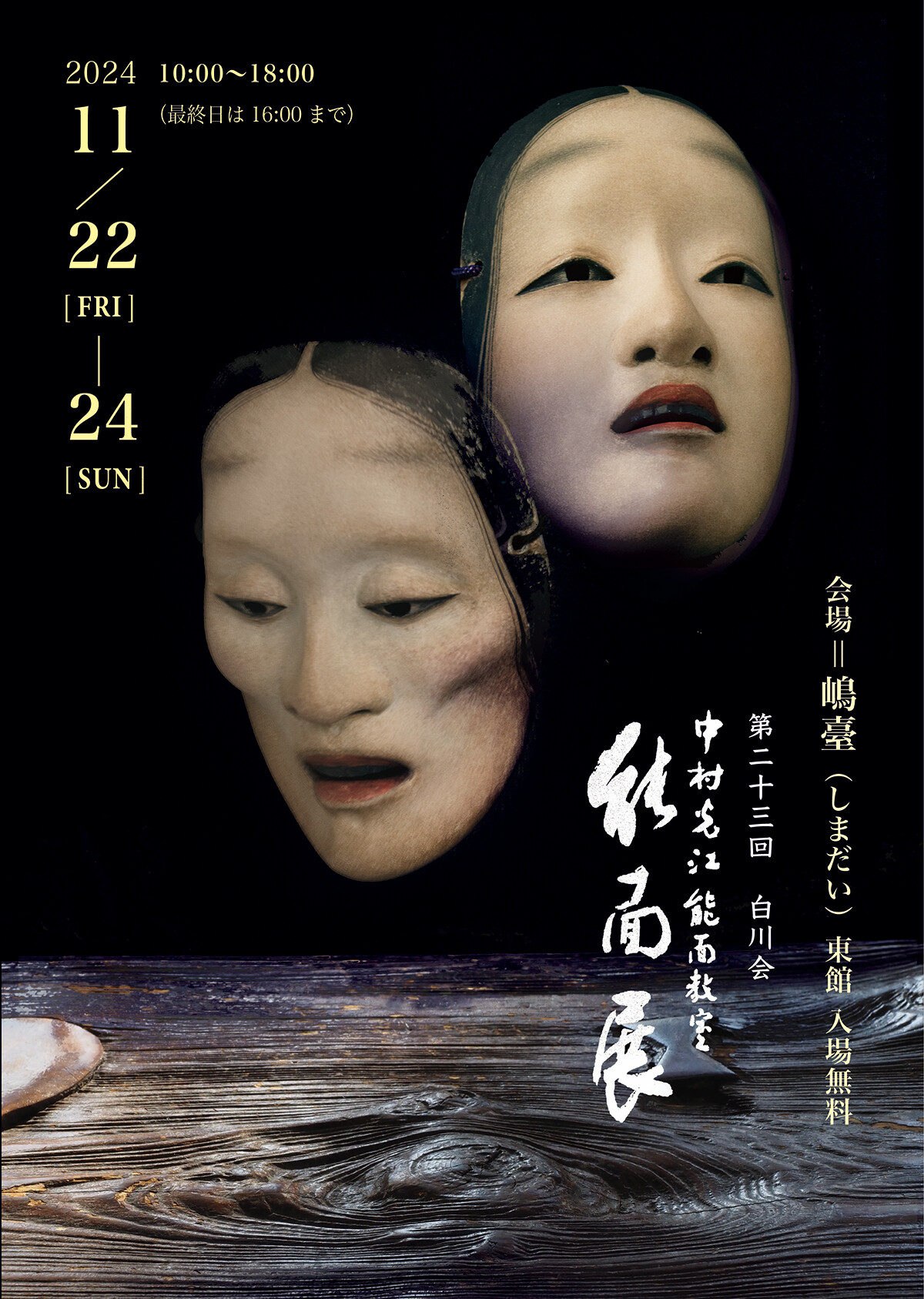

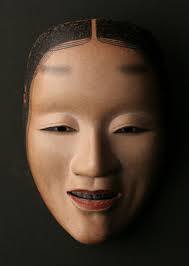

In noh theatre, the mask (nōmen, 能面) is not merely an element of costume. It does not serve to “dress up” or imitate. In a culture where the boundaries between the visible and invisible worlds are seen as fluid, the mask becomes a threshold – a mediating face between actor and spirit, between the present and the timeless, between the body and that which transcends it. It is not, therefore, a prop, but a sacred object of transformation, almost a magical talisman, through which one can become someone else – or rather: cease to be oneself.

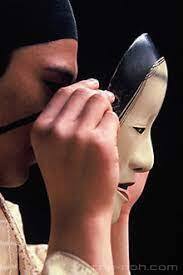

In Western theatre, the actor builds the role – psychologically, emotionally, verbally. They create a character by entering into a dialogue with it. In noh, there is no such dialogue – there is transfiguration. In Japanese, the verb kakeru (掛ける), meaning “to attach” or “to suspend,” is used to describe the act of putting on the mask. One does not say kaburu (“to wear on the head”), as that would suggest something superficial, external. Kakeru has a deeper meaning: the suspension of one’s ego, a passage.

In noh, it is not about individual expression. The shite actor does not express himself – he does not cry, rage, or rejoice “in an actorly manner.” His body is a vessel through which the spirit of the character speaks – often quite literally. In a significant portion of noh plays, especially from the so-called second category (shura-mono), the main character is the spirit of the dead, returning to tell their story and attain liberation (satori) or peace. It is not a human playing a ghost – it is a spirit speaking through a human. Here, noh theatre resembles less what we call theatre in Europe and more a spiritual séance.

In this context, the mask acts as a gate to another world – something between a shamanic trance mask and a religious icon. The actor must “disappear” so that the character may manifest. The audience does not expect realistic gestures – they expect an emanation in which time, identity, and the body are suspended.

Symbolic Meaning

Symbolic Meaning

In Japanese tradition, the spiritual world (霊界 – reikai) permeates reality, yet is separated by an invisible veil. The noh mask functions as a symbolic threshold that separates the everyday from the hidden: memories, grief, unexperienced emotions, the souls of the dead, the eternal archetypes of the woman, the warrior, the madman, the monk, the child.

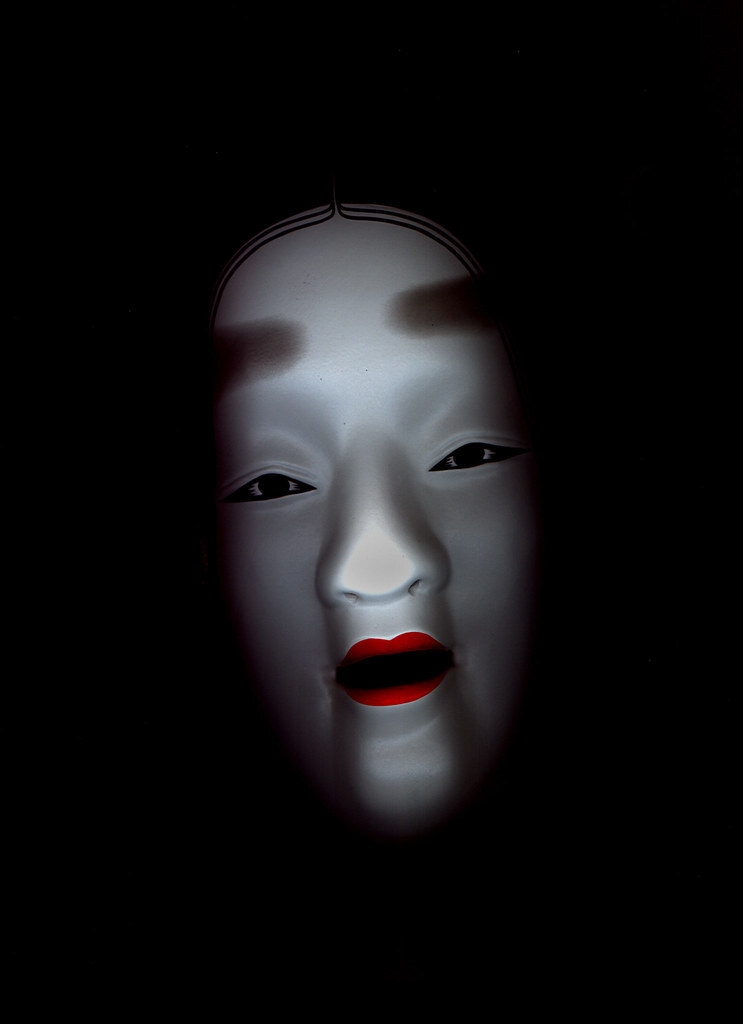

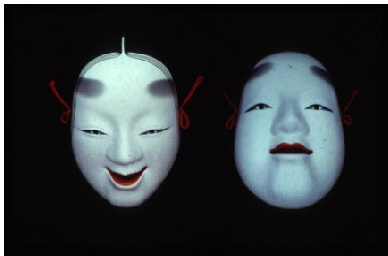

This is why the masks are fixed, and yet full of life. Their secret lies in yūgen – the subtle, mysterious beauty that cannot be expressed in words. Depending on the angle of light and the position of the actor’s head, the expression of the mask may change: terasu (raising – joy), kumorasu (lowering – sadness). It is not the actor’s face that moves – it is the viewer who experiences the variability of emotions that seem to reside within the mask. This illusion of movement without motion is the pinnacle of noh – beauty encapsulated in stillness.

The mask thus becomes an object of projection, but also a mirror of emotions which we, as Europeans, usually seek in facial expressions. In noh, one does not look at the face – one looks through it. And this requires a different kind of perception: the sensing of that which is not directly given.

The Viewing Angle of the Mask

Noh as a Technique of Illusion and Ambiguity

Noh as a Technique of Illusion and Ambiguity

Noh theatre is an art of radical reduction and infinite depth – a theatre of a single object. That object is the nōmen mask, which is not a prop or a costume element, but a concentration of presence, a mediator of emotion, the face and soul of the character, and – ultimately – a metaphor for the human being. In contrast to European acting, which employs a rich palette of facial expressions, in noh the mask is the only face, and its variability stems not from muscle, but from light, angle, and movement. As Zeami, the master and theorist of this art, wrote: “True expression comes from stillness.”

Terasu and Kumorasu – The Chiaroscuro of Emotion

Terasu and Kumorasu – The Chiaroscuro of Emotion

Noh masks are created using very precise and specific techniques. They are carved in such a way as to change facial expression depending on the angle and lighting. Two key technical terms in noh describe the play of emotions through the mask:

► terasu (照らす) – “to illuminate”: a slight raising of the head, which makes the mask appear smiling, serene, inwardly brightened.

► kumorasu (曇らす) – “to darken”: a gentle lowering of the head, which evokes the effect of sadness, melancholy, or anger.

This technique allows for the full emotional spectrum to be achieved with the absolute minimum of means – without moving the mouth or eyes. It is a choreography of gaze, where a movement of just a few millimeters can create in the viewer the impression of a dramatic shift in mood.

Scientific Confirmation – The Chimerical Face

In a psychological study published in PLOS One in 2012 (“The Mysterious Noh Mask”), a team of scientists (Hiromitsu Miyata, Kazuo Okanoya, Nobuyuki Kawai) analyzed how viewers recognize emotions in a noh mask. The results of two experiments are surprising:

► The mask does not convey one consistent emotion. It is a chimera – different parts of the face (brows, eyes, mouth) can express internally contradictory, yet psychologically coherent and complex feelings.

► The mouth plays a key role in emotion perception. More than the eyes or eyebrows, it determines whether the viewer perceives the mask as sad or joyful.

► Importantly, viewers rated masks tilted downward as more joyful, and those tilted upward as more sorrowful – the reverse of noh stage conventions, where terasu = joy and kumorasu = sadness. This means that biological perception may contradict cultural convention, and noh theatre operates on the boundary between these two codes. This further complicates our – Europeans’ – reception of an already distant and difficult theatrical form.

Ambiguity as Refinement

The Mask as a Mirror

All of this leads to one of the deepest functions of the noh mask: it is a mirror that does not show the emotions of the character, but the sensitivity of the viewer. The actor does not “perform” emotion – it is the viewer who experiences it on their own terms. The viewer in noh is not a recipient of narrative, but a co-creator of its spiritual landscape. Yūgen – the inexpressible, mysterious beauty – lies not in revealing, but in suggesting. And ultimately, the creator becomes the observer.

To perceive this harmony, or cacophony of emotions, one must – like the mask – remain silent and wait until the shadow stirs us.

Omote and Ura – The Philosophy of Two Faces

Understanding these terms not only deepens one’s knowledge of noh theatre but, more importantly, helps illuminate the everyday behavior of the Japanese people. Indeed – this is one of the key characteristics that underlies all relationships, worldviews, and forms of social life.

Omote – A Façade, but Also a Form of Care

Omote is what is visible, expressed, presented to the gaze of others. In the social context – it is politeness, restraint, learned roles; a façade, but not necessarily a false one. In the Japanese world of relationships, omote is an act of care for the other – “I do not show you my wounds so as not to burden you.” In noh theatre, omote takes on a literal shape: it is the mask. We see its smooth surface, perfect, silent. But the fact that something is a façade does not mean it is a lie. The mask does not conceal – it prepares the ground for the invisible (the idea that the mask is not a lie is rich and layered – one of its aspects is also explored here: Omoiyari and the Culture of Intuition – The Deepest Difference Between the European and Japanese Mindsets?).

Ura – The Silent Depth

Ura – The Silent Depth

Ura is the inner side, the shadow, the layer that is not shown without significant cause. In interpersonal relationships – it is the emotions that do not fit within the social ritual, such as jealousy, sadness, grief, or authentic longing. In noh, ura is not expressed with words. It is revealed through silence, through the minimal gesture of a hand, a bowed forehead. Ura is the emotion that must not be spoken aloud – and yet “leaks” through, nonetheless. Paradoxically, the mask – as the reverse side of omote – is precisely what makes the emergence of ura possible.

The Mask as Filter and Outlet

The nōmen mask acts as a psychological threshold between worlds: from the actor’s side – it allows them not to be themselves, it becomes a channel (shite) through which the spirit of the character flows. From the viewer’s side – it creates the distance necessary for the truth to be received. In noh, emotion cannot be “acted.” Ura must occur – subtly, without intent, like a sigh that was not planned. This theatre is a ritual of concealment, through which one may speak of that which cannot be said.

Japanese Psychology of Relationships

Carl Gustav Jung wrote of the persona – the social mask we wear to fulfill our roles (yes, this is exactly what the Shin Megami Tensei: Persona game series is about). But beneath it lurks the shadow – all that is repressed, unaccepted, hidden. In this sense, noh is theatre of the shadow. But unlike Western psychodrama, which seeks confrontation and catharsis, noh does not lift the veil. It gently stirs it – so that a fragment of truth may dance in the shadows.

In Western theatre, emotions explode. In noh – emotions condense and are filtered through form. It is precisely form, ritual, mask, style – that create the space where ura may resound, without destroying either the actor or the viewer. It is a theatre of delicate courage – the courage not to say everything, but to give space for something to emerge. Like an echo that remains long after everything has fallen silent.

The Psychology of the Mask – Who Am I When I Am Not Myself?

The Psychology of the Mask – Who Am I When I Am Not Myself?

In noh theatre, the mask is not a costume – it is a passage, a mechanism that dissolves the ego, a vehicle for spiritual shifting. We do not wear it to hide ourselves – we wear it to disappear. When the shite enters the kagami-no-ma – the “mirror room” – and affixes the mask (kakeru), he does not become someone else in a psychological sense. He ceases to be anyone at all. Thus begins the practice of mushin no kan (無心の観) – “seeing without mind,” a state devoid of assumptions, expectations, self.

Mushin no kan – Seeing Through Emptiness

In zen tradition, mushin (無心) is the absence of mind – the absence of attachment to one’s own emotions, thoughts, desires. Zeami, the founder of classical noh theatre theory, wrote that the actor should “see without thinking,” be present without intention, perform without “performing.” The mask not only hides his face – it removes his center of identity, takes the personal “I” out of the way, so that the spirit of the character (reikon 霊魂) may enter. It is not the actor who “plays” the dead hero – it is the spirit of the dead who uses the actor’s body as a channel.

Zeami wrote in the treatise Fūshikaden that the actor should be like a mirror – formless, transparent, free. If he brings himself – his emotions, his style, his pride – he gets in the way. “There must be no personality in the one who carries the mask,” says one classical instruction. The nōmen mask does not work if a “performing person” looks out from behind it. It only works when the viewer – through it – encounters themselves.

From this perspective, noh theatre is not entertainment – it is meditation, a spiritual experiment. The actor – and the viewer – are not meant to understand the character’s emotions, but to disappear in the presence of something that transcends individual psychology.

Everyday Life as a Theatre of Masks

In our lives we wear omote – social masks: professional faces, pleasant expressions, postures of competence, care, strength. And we often forget that these are only functions, not identity. Noh reminds us: a person is a role – but not role-playing. We have no center. We are a moving stage on which various masks appear. And beneath them – emptiness. But not emptiness in the Western sense – an emptiness of potential, of possibility, of readiness for whatever may arise.

The nōmen mask teaches us a paradox: the deepest “self” is discovered when we cease to identify with it. The mask does not erase identity – it reveals that identity was never truly anything stable. Someone else enters us – a spirit, a memory, an archetype – but the fact that it could enter shows that we were never “ourselves” in any absolute way.

Can We Learn Something from Noh Masks?

The experience of noh theatre – slow, ritualistic, ascetic – is like a mirror held up to our everyday lives. It shows us that one can exist without constant self-presentation, that a role can be deeper than the “I,” that emotion can be more present when it is not revealed directly. The mask, instead of concealing, protects – from excess, from banality, from exposure that cannot be undone.

In an age of digital loquacity, noh reminds us that speech is only the surface. Beneath it pulses ura – the silent, unspoken depth that needs the mask.

Finally – noh tells us that authenticity is not emotional exhibitionism, but the ability to be a channel for something greater than ourselves. “Be yourself” too often means “be louder than others” – the mask becomes a way out of false authenticity. It reminds us that you are most true when you allow something to speak through you.

That is why it is sometimes worth standing in the kagami-no-ma of your own life. To look yourself in the eyes – and disappear behind the mask. Even if only for a moment.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

The Majime Mask - The Japanese Soul Torn Between Inspiring Ideal and Enslaving Whip

The Monk with the Naginata: The Martial Face of Buddhism in Kamakura Japan

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

Mastering One’s Desires: The Solitary Path of Musashi and Aurelius

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Symbolic Meaning

Symbolic Meaning Noh as a Technique of Illusion and Ambiguity

Noh as a Technique of Illusion and Ambiguity Terasu and Kumorasu – The Chiaroscuro of Emotion

Terasu and Kumorasu – The Chiaroscuro of Emotion

Ura – The Silent Depth

Ura – The Silent Depth

The Psychology of the Mask – Who Am I When I Am Not Myself?

The Psychology of the Mask – Who Am I When I Am Not Myself?