Cats in Japanese History and Ukiyo-e Art – How These Furry Tricksters Took Over the Land of the Samurai

Feline Rulers

Don’t think that in Edo-period woodblock prints, cats were limited to peacefully dozing on tatami mats. Artists took it a step further—transforming them into samurai, kabuki actors, and even entire cities (yes, I am referring to Kuniyoshi’s brilliant parody of the Tōkaidō route, where the travel stations were turned into feline escapades). Ukiyo-e proved that cats were far more than just soft fur and a talent for ignoring human commands. They were symbols of freedom, mischief, and sometimes—even against their own reluctant nature—tools of political satire.

Cats in Japan – A Bit of Feline History

Where Did Cats Come From and When Did They Arrive in Japan?

Beyond their practical function, cats also took on a symbolic role in Japanese Buddhism. Their calm, almost meditative demeanor, mysterious gaze, and ability to “read minds” (a.k.a. the classic feline stare that makes humans feel like idiots) made them creatures of profound spiritual significance. Over time, cats became not only guardians of sacred texts but also sentinels of the spiritual world, which translated into their presence in art, folklore, and daily life in Japan.

Cats Among the Samurai

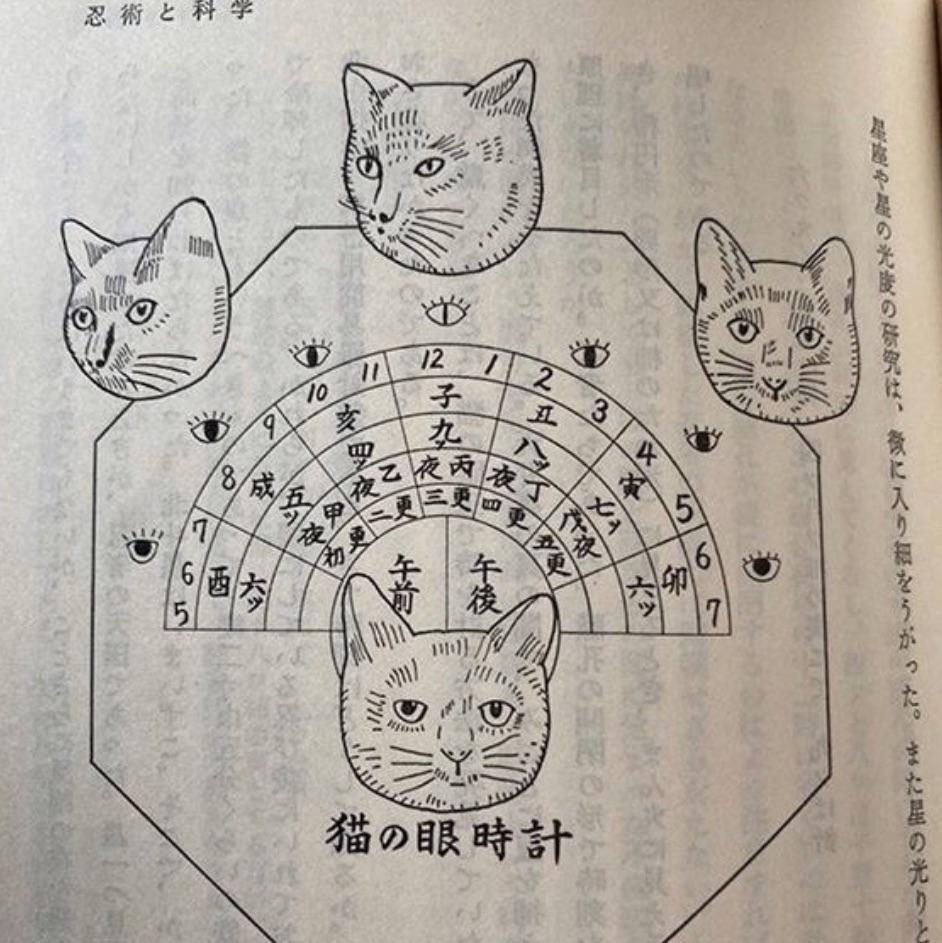

The Sengoku period (1467–1603), an era of incessant civil wars, forced both humans and cats to adapt to an uncertain reality. Some legends claim that samurai kept cats in their castles as “living clocks”—supposedly observing feline pupils, which changed shape depending on the time of day. Wait, were cats really used as timepieces?

There’s even an old Japanese text from the Edo period titled Myōkeihyō (妙形表), which describes this method, attributing to cats the role of living biological clocks. Of course, in practice, it was hardly a precise system, but it highlights how carefully the Japanese observed animals and how deeply they believed in their extraordinary abilities—especially when it came to cats.

Cats in Edo and Beyond

And what about the Meiji period (1868–1912)? Japan’s modernization and opening to the West meant that cats began functioning more as household companions rather than just “heroic hunters of the community.” The first animal welfare organizations appeared, and maneki-neko—the famous “beckoning cat” figurine—became an almost national symbol of good fortune. But before we get to that, it’s worth diving deeper into Japanese folklore, because cats had long held a reputation for being creatures that were anything but... ordinary.

Cats in Japanese Literature and Folklore

The Oldest Japanese Mentions of Cats – Nihon Ryōiki

The Oldest Japanese Mentions of Cats – Nihon Ryōiki

The first written references to cats in Japan come from Nihon Ryōiki, the oldest collection of Buddhist stories from the 9th century. Although we can't yet speak of cats as literary stars at this point, even then, these animals were described as mysterious, possessing extraordinary abilities, and—most importantly—being linked to the spirit world.

Kara Neko – The Cat That Changed the Course of The Tale of Genji

If we are looking for the first cat to truly stir things up in literature, we’ll find it in The Tale of Genji (11th century), the classic novel by Murasaki Shikibu (more about her here: The Author of the World's First Novel: Meet the Strong and Stubborn Murasaki Shikibu (Heian, 973) And about The Tale of Genji here: Genji and Yugao – The Secrets of the Moonflower in a Millennium-Old Tale of Desire and Loss). Kara Neko, or the “Chinese Cat,” in one dramatic scene, tears down a curtain, revealing a hidden princess to the protagonist. Sounds innocent? Well, as a result of this “feline intervention,” a romance blossoms, leading to an illegitimate child and a series of events that alter the entire course of the story. This might just be the first proof that cats are not only adorable but also incredibly influential.

Cats as Supernatural Beings

▫ Bakeneko (化け猫) – "The Shape-Shifting Cat"

▫ Bakeneko (化け猫) – "The Shape-Shifting Cat"

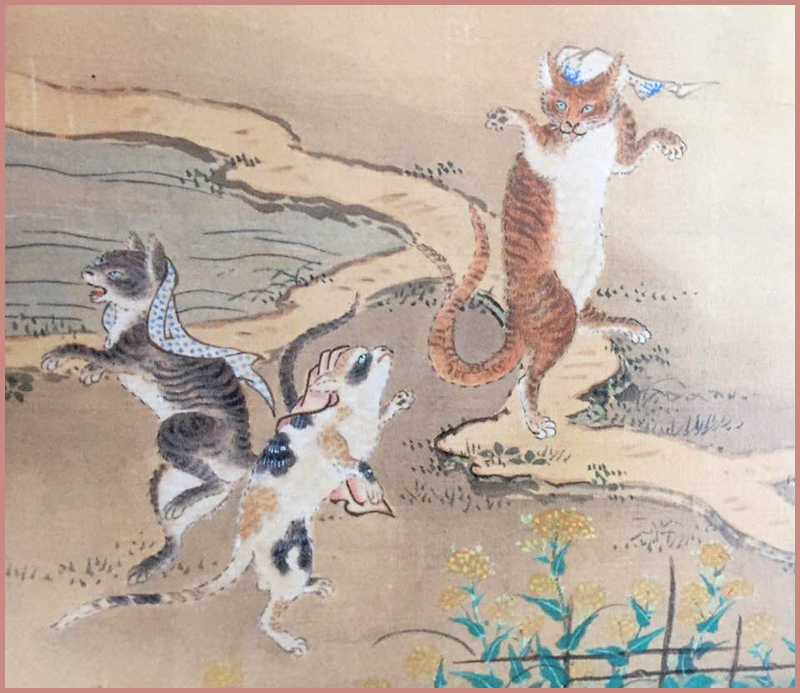

A cat that, after reaching a certain age, could walk on two legs, speak in a human voice, and... plot revenge against its owners. Some bakeneko had the ability to control fire, while others could take on human form to manipulate their surroundings (more about bakeneko here: Vengeful Cat Demons in Japanese Legends: The Sinister Bakeneko).

▫Nekomata (猫又) – An Even More Fearsome Version of Bakeneko

A cat whose tail split into two, granting it even greater powers. It was believed that nekomata could resurrect the dead, making them the central figures in many horror stories from the Edo period.

But lest we get too caught up in the horror—cats also had a positive reputation. It was believed that they could ward off evil spirits, and their presence in a household ensured peace and prosperity.

Cat Motifs in Ukiyo-e

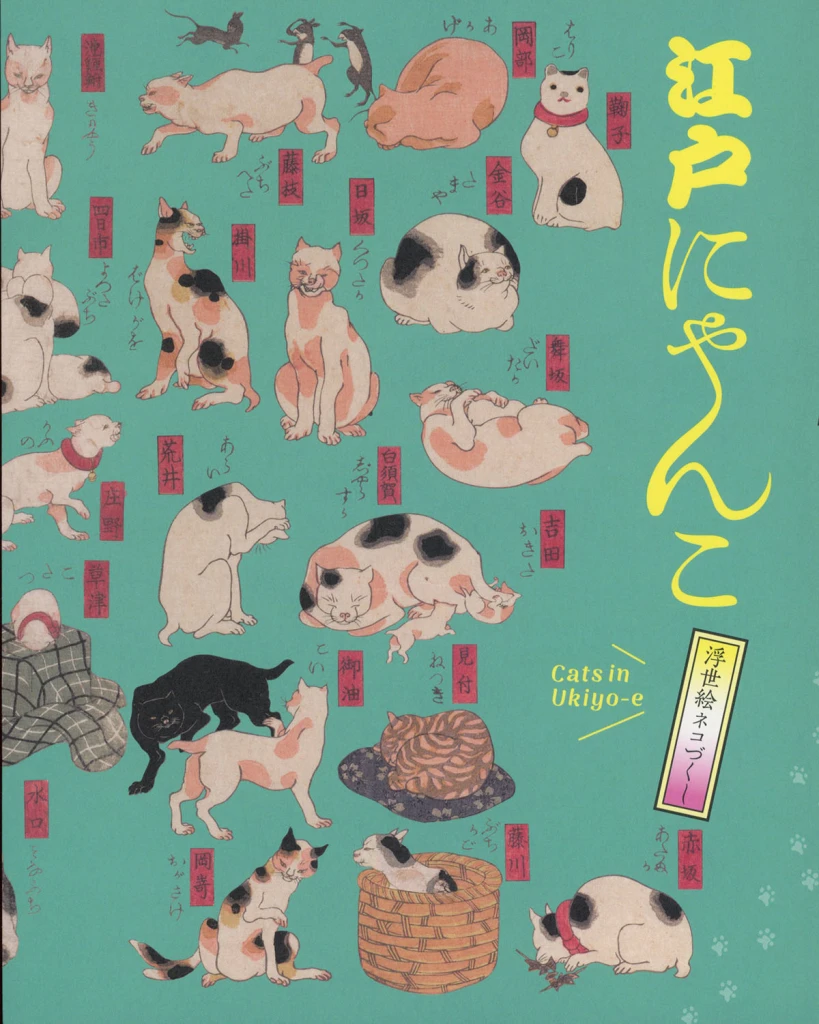

One of the reasons for their immense popularity was the sheer number of cats in Edo—nearly every household had a four-legged companion, and the animals roamed the streets and countryside freely. Naturally, this led artists to not only incorporate them into their works but to make them central figures. From simple domestic scenes to parodies of famous artworks, and even surreal and grotesque depictions—Japanese woodblock prints are filled with cat motifs that continue to captivate art lovers to this day.

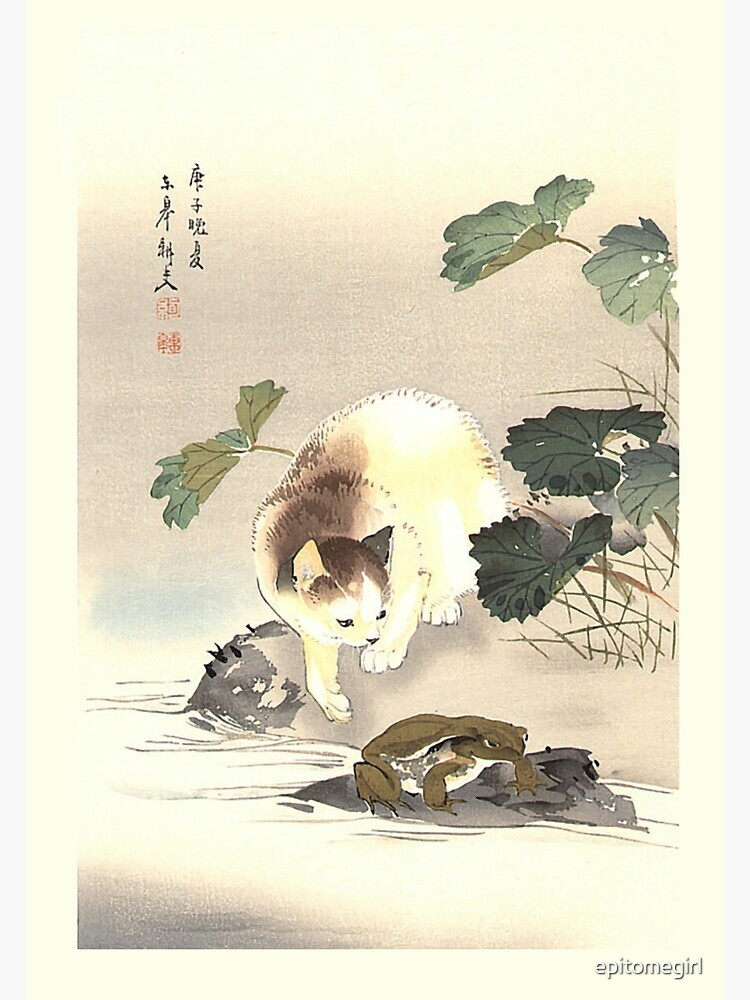

Cats in Their Natural Environment

Edo-period woodblock prints showcase entire galleries of cats curled up in sleep, lazily stretching after a nap, playfully pawing at strings (because, in the 19th century, no one had yet invented laser pointers), or meticulously grooming themselves with a seriousness and precision worthy of a samurai’s blade. Many of these depictions are so lifelike that one might imagine the artists spent hours closely observing cats before committing their movements to print.

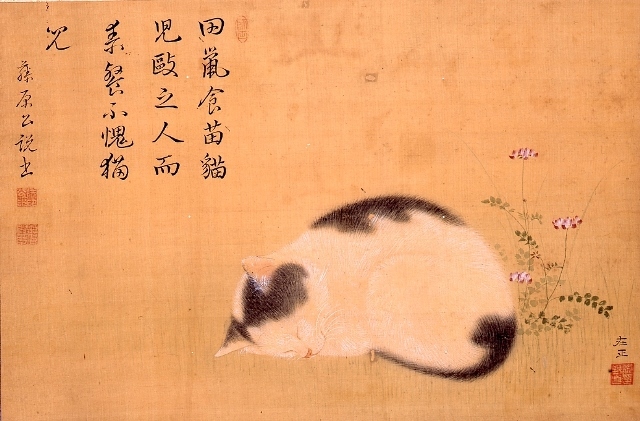

Many ukiyo-e featuring cats are not just cute images but also compositions rich in symbolism. Cats depicted in deep sleep could symbolize domestic peace, while those hunting mice represented vigilance and protection against misfortune. In Japan, it was believed that a home with a cat was a home free of evil spirits, and ukiyo-e reflected this belief, portraying cats not only as household companions but as guardians of human happiness.

It was in this naturalistic form that cats first gained popularity in art, but over time… they began taking on increasingly unusual roles. Because surely no one thought that ukiyo-e artists would stop at mere realistic cat portraits.

Cats and People

One of the best examples of this relationship is Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s woodblock print titled “Ouch! That Hurts!” (痛い、痛い!), part of the Auspicious Pictures of Land and Sea series (circa 1847–1852). It depicts a woman in an elegant kimono smiling amusedly as her cat energetically digs its claws into her arm. This is a scene any cat owner can relate to—Japanese felines had already mastered the art of asserting dominance in the household.

Another fascinating example is “The Joy of First Snow” (初雪の戯れ) by Kuniyoshi, where a cat perches on a woman’s lap as she gently cradles it. The scene radiates warmth and tranquility, emphasizing the bond between humans and animals. In Japanese culture, cats often symbolized domestic happiness and harmony—their presence in such intimate moments underscored familial comfort and stability.

A different atmosphere is captured in “A House Cat Sleeping on a Woman’s Kimono” (愛猫と美女) by Utagawa Toyokuni I (circa 1810). Here, a cat peacefully sleeps on a woman's kimono as she rests beside it. During the Edo period, it was commonly believed that a cat sleeping near its owner brought them good fortune and warded off evil spirits—making this scene not only an everyday image but also one with deeper symbolic meaning.

The Symbolism of Domestic Cat Scenes in Ukiyo-e

The symbolism of domestic cat scenes in ukiyo-e is incredibly rich. Cats were often depicted as metaphors for human traits—both positive and negative. In Japanese culture, they were associated not only with loyalty and independence but also with cunning and mystery. In some cases, cats served as allegories for seductive women or hidden deception, a theme frequently appearing in scenes depicting courtesans from Yoshiwara.

One of the most interesting examples of this symbolism is the woodblock print "Courtesan Sleeping with a Cat" (猫と遊女), where a cat sleeps beside a luxuriously dressed oiran. In Edo art, cats often accompanied figures with a dual nature—much like geisha or courtesans, who blended charm with an air of mystery in their profession.

Cats as Humans – Anthropomorphism in Ukiyo-e

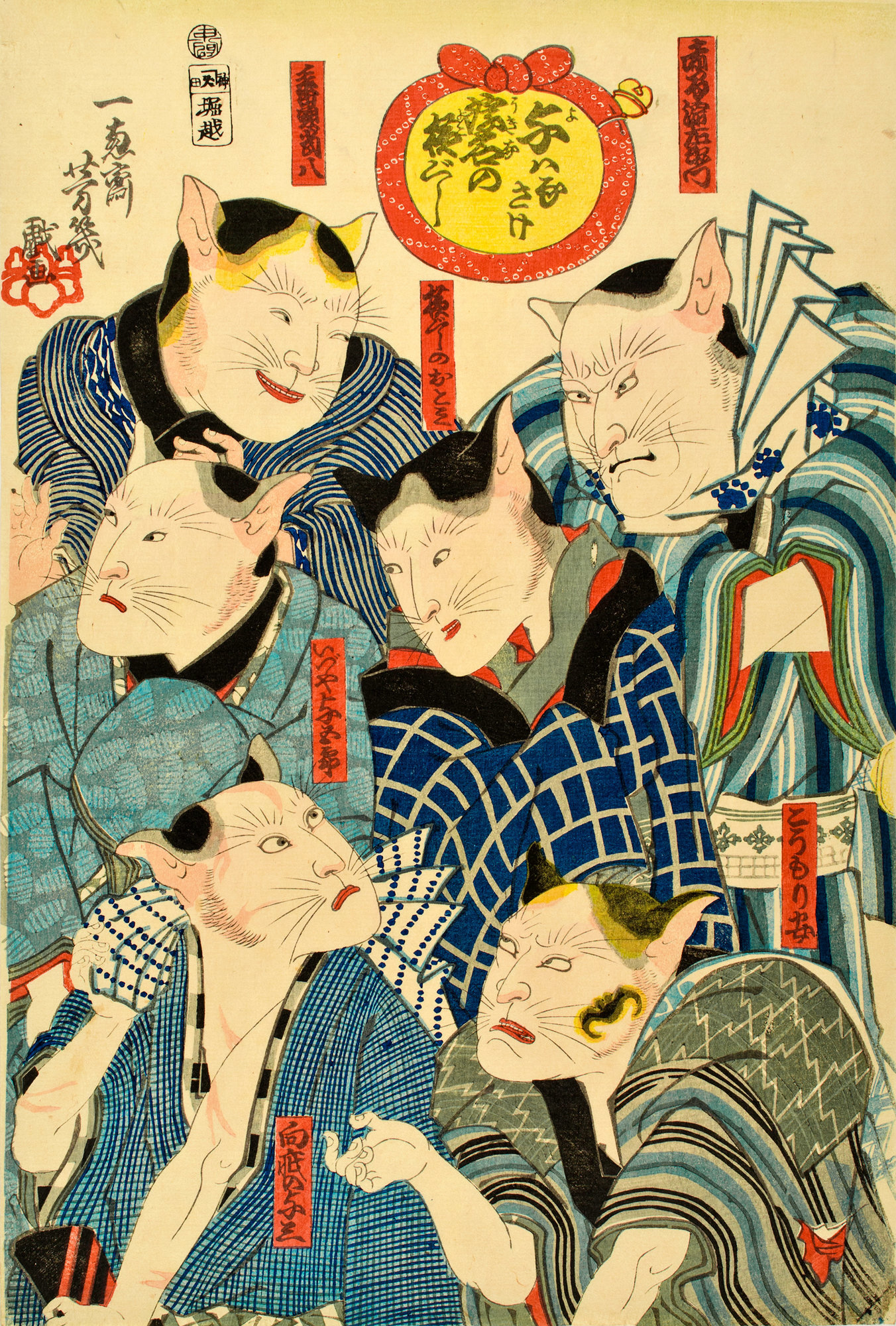

In ukiyo-e, cats were not limited to sleeping, hunting, and playing—over time, they also began... walking on two legs, wearing kimonos, and taking on human roles. Edo-period artists, led by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, delighted in the motif of feline anthropomorphism, using their natural expressions and behaviors to create humorous and sometimes satirical images. Cats became symbols of social archetypes, kabuki stars, and even tools of subtle political critique that cleverly circumvented shogunate censorship.

Cats as Humans – Satire on Edo Society

Cats as Humans – Satire on Edo Society

In ukiyo-e, cats often served as a mirror of human behavior—adopting postures, gestures, and clothing styles that humorously reflected Edo-period social life. One of the best examples is the woodblock print "Fashionable Cats Juggling Balls" (流行猫曲芸) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (circa 1842), in which cats appear as circus acrobats, juggling balls while dressed in Edo-era attire.

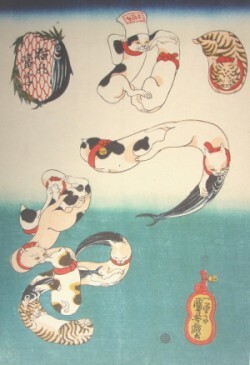

An even more amusing and detailed vision of the "cat-human" world was presented by Utagawa Yoshifuji in the extraordinary print "Tiny Kittens Combine to Form a Giant Cat" (小猫組み合わせ大猫). Here, individual cats come together to create the image of one enormous feline—a clever metaphor for Edo's social structure, where individuals formed a greater whole.

These prints had a dual function—they entertained Edo’s citizens while also carrying hidden messages. Cats symbolized not only the playful side of human nature but also hypocrisy, vanity, and social intrigues.

Cats as Kabuki Actors – Censorship-Proof Critique of the Shogunate

But ukiyo-e artists were not about to give up so easily. Kuniyoshi, known for his wit and ingenuity, found a way to outmaneuver censorship—rather than depicting people, he replaced them with cats dressed as kabuki actors. This led to series like "Cats Performing in Kabuki Plays", where feline characters clearly resembled famous actors and theatrical roles.

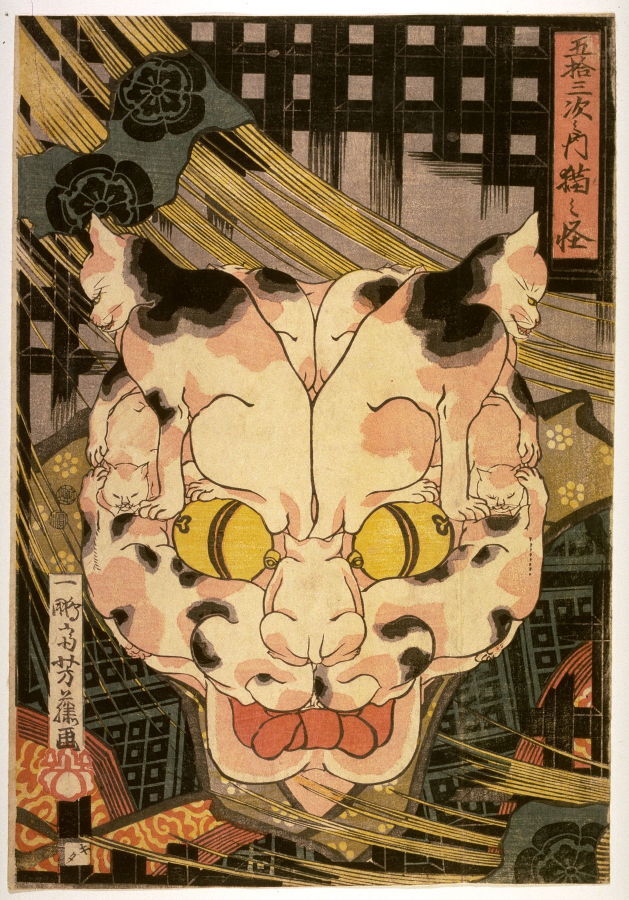

A particularly intriguing example is "Kabuki Actor Onoe Kikugorō III as the Spirit of the Cat Stone" (歌舞伎役者猫石霊) by Utagawa Kunisada (1852). It depicts the renowned actor Onoe Kikugorō III in the role of a spectral cat from a popular kabuki play. The image of a massive feline looming from a lantern references a famous horror scene that captivated Edo-period audiences.

"Neko no Ateji" – Cats as Written Characters and a Play on Words

"Neko no Ateji" – Cats as Written Characters and a Play on Words

Kuniyoshi didn’t just transform cats into people—he also turned them into... Japanese characters! In his series "Neko no Ateji" (猫の当字), or "Cat Homophones", he illustrated cats forming the shapes of written kanji characters. Each image played on words related to fish names—an ingenious marketing trick for Edo’s cat lovers and food enthusiasts alike.

One of the most famous prints in this series depicts cats forming the characters for katsuobushi (dried bonito), a beloved delicacy among Japanese cats. This highly creative series highlights not only Kuniyoshi’s artistic ingenuity but also his deep understanding of feline behavior—his cats act completely naturally, even when arranging themselves into the shapes of kanji.

"Cats Suggested as the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō" – Kuniyoshi’s Brilliant Parody of Hiroshige

At the pinnacle of the most inventive ukiyo-e cat depictions stands one of Kuniyoshi’s greatest masterpieces—"Cats Suggested as the Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō" (猫の東海道五十三次), published in 1852. This series parodies the famous "Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō" by Utagawa Hiroshige, which depicted scenic landscapes and travelers along the road from Edo to Kyoto (analysis of that series here: "The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō" by Hiroshige – The Journey Is Not the Destination, but What We Pass Along the Way).

In Kuniyoshi’s version, instead of landscapes and journeying figures, we see… 55 cats, each representing a station on the Tōkaidō route. Some amusing examples:

Miya (41st station) sounds similar to oya (親), meaning "parent," so Kuniyoshi depicted a cat family: two kittens snuggling close to their mother.

- Ishibe (55th station) resembles the word mijime (惨め), meaning "miserable," so this illustration features a sad, exhausted-looking cat.

- Shirasuka (33rd station) sounds like shirasu (白須), referring to tiny white fish commonly used in Japanese cuisine. In the image, a cat is reaching out its paw toward a bowl of fish—a classic feline instinct!

- Fujisawa (6th station) resembles the word fuji (藤), meaning wisteria. Kuniyoshi depicted a cat curled up beneath cascading wisteria branches, creating a serene, almost poetic scene.

- Yui (17th station) sounds like yui (結い), meaning "to bind" or "to weave." The illustration shows a cat playing with a string or tangled in fabric, reflecting both the word’s meaning and a typical feline behavior.

This series is a true ukiyo-e gem—combining visual humor with linguistic playfulness. Once again, Kuniyoshi demonstrated that cats are not just perfect subjects for realistic portraits but also excel in satirical and parodic compositions.

Beyond Edo – Cats Still Rule Japanese and Global Culture

And let’s not forget the greatest, smartest, and all-around most magnificent feline character in the history of human creativity—Morgana from Persona 5.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Vengeful Cat Demons in Japanese Legends: The Sinister Bakeneko

The Shogun Introduces Animal Cruelty Laws in 17th-Century Edo Japan

Why Does Japan Still Hunt Whales? A Bureaucratic Relic That Nobody Wants

Overview of Nico Nico Douga's Domestic Scene - What Drives the Japanese?

Ukiyo-e “Moon Over Daimotsu Bay”: Yoshitoshi’s Mighty Benkei Among Ghostly Clouds

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

The Oldest Japanese Mentions of Cats – Nihon Ryōiki

The Oldest Japanese Mentions of Cats – Nihon Ryōiki

▫ Bakeneko (化け猫) – "The Shape-Shifting Cat"

▫ Bakeneko (化け猫) – "The Shape-Shifting Cat"

Cats as Humans – Satire on Edo Society

Cats as Humans – Satire on Edo Society

"Neko no Ateji" – Cats as Written Characters and a Play on Words

"Neko no Ateji" – Cats as Written Characters and a Play on Words Miya (41st station) sounds similar to oya (親), meaning "parent," so Kuniyoshi depicted a cat family: two kittens snuggling close to their mother.

Miya (41st station) sounds similar to oya (親), meaning "parent," so Kuniyoshi depicted a cat family: two kittens snuggling close to their mother.