Winter Whispering Dreams: 10 Names for Snow in the Japanese Language

Snow as a Key to Mindfulness

Haiku poetry, in its brevity, captures these fleeting moments beautifully. Masaoka Shiki’s haiku illustrates how poetry draws inspiration from the different forms of snow:

根雪解く 音かすか也 昼の月

(Neyuki toku / Oto kasuka nari / Hiru no tsuki)

“Rooted snow melts—

a barely audible sound;

the midday moon.”

Shiki’s haiku captures the moment when humans deeply resonate with nature's subtle shifts. As neyuki melts, it becomes more than just a landscape feature—it transforms into a metaphor for endurance and strength, offering proof that patience and humility can see us through even the longest of winters.

In Japan, snow symbolizes silence and introspection, but also memories and dreams. Each of the ten snow-related terms we will explore is not merely a word but a key to understanding the Japanese soul. The language unveils the world's impermanence in all its extraordinary fullness. Snow gently settling on bamboo leaves, filling the valleys of yukiguni, or quietly accompanying the final winter nights, is not merely a natural phenomenon—it is an experience of life lived in acceptance of transience. Mono no aware.

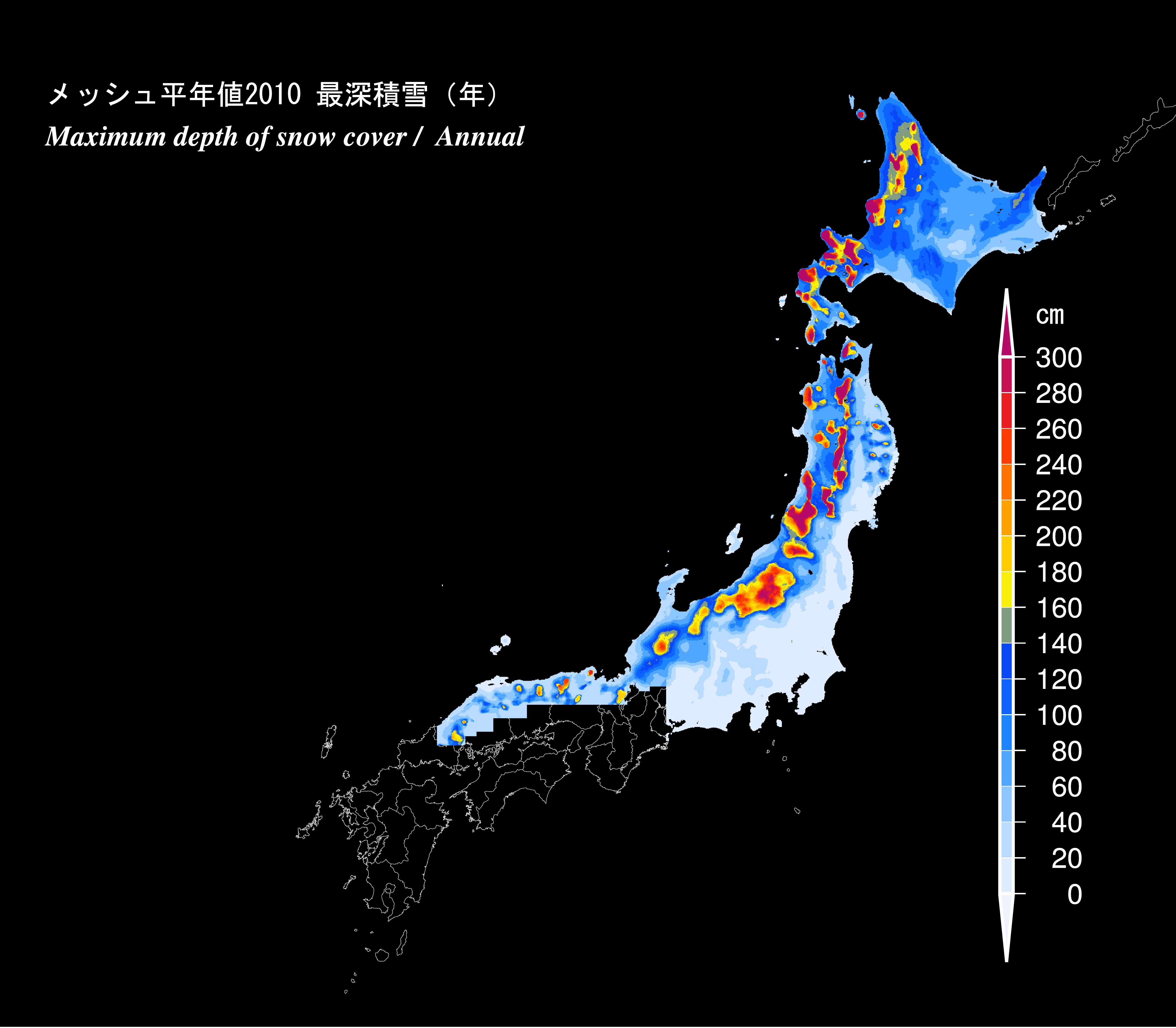

A Mosaic of Climates

In the far south, Okinawa, where the climate resembles that of Hawaii, winter is almost imperceptible. The average temperature in January is around 17–18°C (63–64°F), and instead of snow, the islands are covered with green sugarcane fields and hibiscus flowers. During winter, Okinawans stroll along the beaches, nurture traditions like shīsa matsuri (festivals associated with mythical lion guardians), and rarely encounter the conditions considered routine in northern Japan.

But we move further north. It is northern Japan—Hokkaido and the regions known as yukiguni (雪国, "snow country")—that is the true winter wonderland. These areas are famous for massive snowfall, which can reach several meters in height. In towns like Aomori or Yamagata, winter is no longer just a beautiful backdrop—it is a force of nature shaping every aspect of life. Houses with steep roofs seem to sink into the whiteness, while residents create tunnels and paths through the snowdrifts to move between buildings. In yukiguni, snow layers can exceed a person’s height—snow removal here truly means digging tunnels (read more about yukiguni here: Yukiguni – What Life Lessons Can Be Learned from Japan’s Snow Country?).

In prefectures like Niigata, Akita, or Toyama, residents have learned to live in harmony with winter. They build sturdy houses with small windows to retain heat and use modern technologies such as heated roads and snow-melting systems (including heated sidewalks, intersections, and autonomous snow-clearing drones—after all, this is Japan). However, even in these harsh conditions, winter is a time of joy. In the yukiguni regions, snow festivals are popular, such as the Yokote Kamakura Festival, where traditional snow huts (kamakura - かまくら, not to be confused with Kamakura: 鎌倉, the name of a city and historical era of the first shogunate) are built and illuminated with lanterns, creating a magical, almost fairytale-like landscape.

初雪や しっぽり濡れて 鶴の足

(Hatsuyuki ya / shippori nurete / tsuru no ashi.)

“First snow—

wet and heavy

the crane’s legs.”

Let us now explore how the Japanese speak about snow. Language is more than a tool for communication—it is a mirror reflecting the way its speakers think, perceive the world, and live their daily lives. As Edward Sapir noted, language not only describes reality but shapes it, revealing the unique ways a culture experiences the world. In Japan’s case, the rich vocabulary associated with snow unveils not only a fascination with winter’s nature but also a profound respect for its subtle nuances. Here are ten Japanese words for snow that will allow us to delve into the Japanese soul and its relationship with nature.

Snow in Japanese

1. Yuki (雪) – “snow”

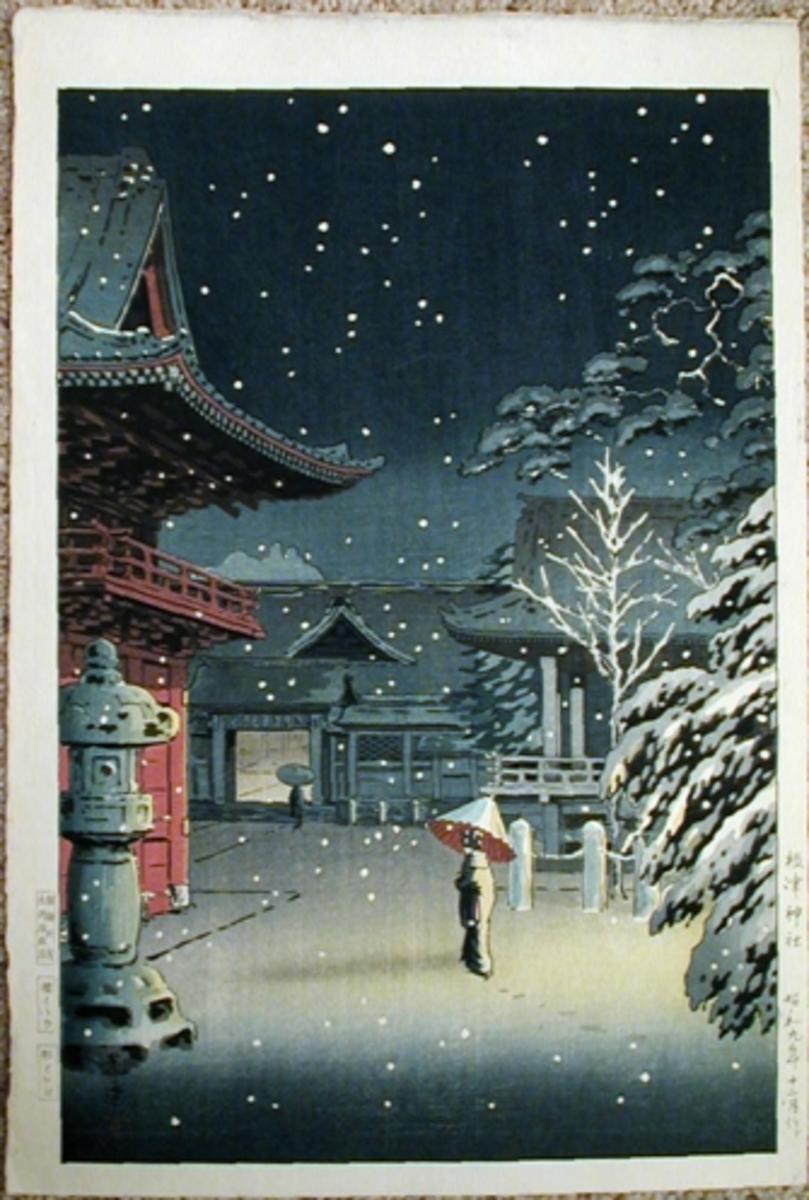

Yuki is used in both formal and everyday situations, making it the most fundamental word for snow. In poetry and art, yuki represents purity, tranquility, and transience. Especially in the aesthetic of wabi-sabi, snow symbolizes the beauty of impermanence, which is central to the Japanese mindset. Winter landscapes, such as snow on bamboo leaves or snow settling on temples, are frequent motifs in literature, painting, and Noh theater.

2. Fubuki (吹雪) – “snowstorm”

In literature and art, fubuki often symbolizes challenge, harshness, and the relentless character of winter. In traditional stories, snowstorms can mislead travelers or test their strength and survival skills. In haiku by masters like Bashō or Buson, fubuki is often portrayed as a backdrop for human loneliness or struggles against adversity. In northern Japan, such as Hokkaido or Aomori Prefecture, fubuki is a frequent visitor in winter, especially in January and February when cold winds from Siberia are at their strongest.

吹雪の中 泊りあかすや うば車

(Fubuki no naka / tomari akasu ya / uba-guruma.)

“In the snowstorm,

spending the night alone—

an old woman’s cart.”

An interesting aspect of fubuki is its appearance in Japanese theater and cinema. In classical Noh or Kabuki plays, snowstorms often serve as the backdrop for dramatic events—symbolizing chaos or inevitable change. In pop culture, especially in anime and manga, fubuki frequently accompanies climactic moments, emphasizing intense emotions in characters.

3. Konayuki (粉雪) – “powder snow”

Konayuki is typical during the winter months in Hokkaido, where low temperatures and specific atmospheric conditions create “dry snow.” This means the snow does not clump together but falls as fine, almost magical flakes. In Niseko, Japan’s famous winter capital, konayuki attracts winter sports enthusiasts from all over the world. It is said that skiing on this snow feels like “floating on a cloud”—a nearly spiritual experience.

In Japanese culture, konayuki symbolizes fragility and the beauty of fleeting moments. In poetry and music, it refers to the subtle emotions associated with winter. The popular Japanese ballad “Konayuki” by the band Remioromen tells a story of love and melancholy, using the metaphor of delicate snowflakes that fall quietly and leave no trace. The word is not just a technical description of snow but also demonstrates the Japanese emotional connection to nature—a quiet yet deeply moving beauty.

“粉雪 ねぇ

心まで白く 染められたなら

あぁ 二人の孤独を分け合うことができたのかい”

(Konayuki nee / kokoro made shiroku someraretara / aa futari no kodoku o wakeau koto ga dekita no kai)

“Powder snow, hey,

if it could whiten even our hearts,

ah, could we have shared our loneliness?”

4. Shimo (霜) – “frost”

In Japan, shimo is a symbol of early winter mornings—filled with silence and tranquility. It can be seen on rooftops, tree branches, or blades of grass, which, covered in small, sparkling crystals, resemble tiny jewels. In haiku poetry, frost symbolizes impermanence, delicacy, and transience. An example is a poem by Kobayashi Issa:

霜の朝 牛はつめたき 鼻をふく

(Shimo no asa / ushi wa tsumetaki / hana o fuku.)

“Frosty morning—

the cow’s cold nose

exhales steam.”

Frost is also connected to Japan’s agricultural traditions. During the period of shimo-tsuki (霜月, “month of frost,” November), Japanese farmers finish their work in the fields and prepare for the winter rest. This short-lived and ephemeral phenomenon teaches mindfulness, which is an essential element of Japanese philosophy of life.

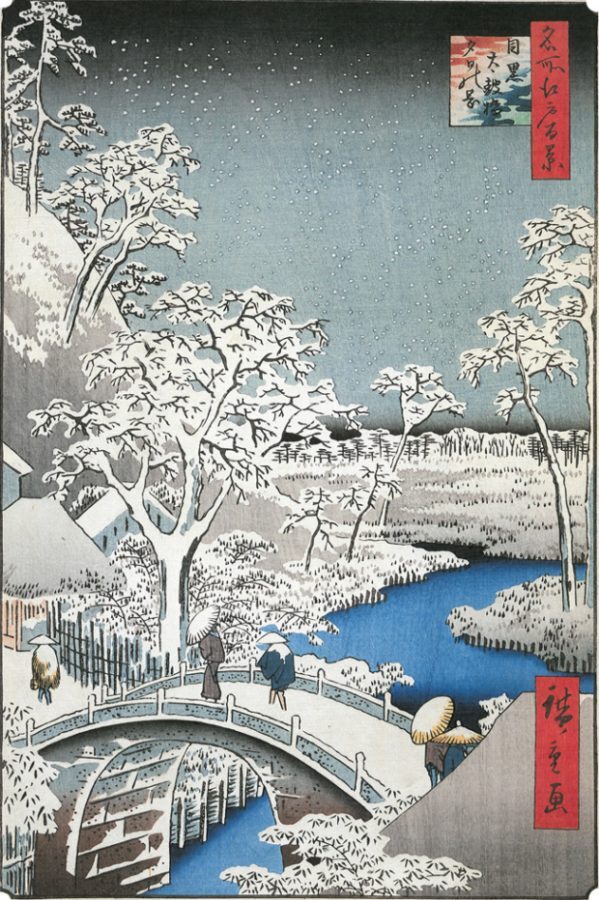

5. Botan-yuki (牡丹雪) – “Peony Snow”

Botan-yuki holds deep aesthetic significance. In Japanese culture, peony snow is associated with silence and reflection, its soft descent carrying an almost meditative quality. In painting, especially in the ukiyo-e style, botan-yuki frequently appears in winter landscapes, contrasting with the dark silhouettes of trees or pagodas.

In literature and Noh theater, botan-yuki serves as a symbol of transient beauty. This is snow that does not last long, melting shortly after touching the ground. Poetically, it represents the passing of life, aligning perfectly with the aesthetic of mono no aware. Observing this snow evokes both awe and nostalgia, with an awareness of its impermanence.

6. Sasa-yuki (笹雪) – “Snow on Bamboo Leaves”

Sasa-yuki is a symbol of the subtle beauty of nature and carries profound aesthetic meaning. The image of delicate snow on bamboo leaves appears in painting, poetry, and garden art. It exemplifies the harmony between winter and nature—despite the weight of the snow, the bamboo leaves, bent but unbroken, rise again toward the sky.

7. Namida-yuki (涙雪) – “Snow Tears”

Namida-yuki symbolizes fleeting moments and melancholy, often found in Japanese aesthetics. This type of snow typically appears toward the end of winter or the beginning of spring, when nature is preparing for renewal. It is snow that evokes sadness but also acceptance of the passage of time. In Japanese culture, it is a natural metaphor for bidding farewell to winter.

Namida-yuki is a frequent motif in Japanese poetry and literature. Haiku and tanka describe it as a momentary, ephemeral event, reminding us of the fragility of human life. In Noh theater, snow tears can symbolize the pain of separation, longing, or unfulfilled love. Kobayashi Issa writes about it in this haiku:

涙雪とけて 村一ぱいの 子ども哉

(Namida yuki tokete / mura ippai no / kodomo kana.)

“The snow melts, like tears—

the village full of children,

all running outside.”

8. Mizore (霙) – “Snow with Rain”

Mizore symbolizes a moment of uncertainty as nature prepares for the arrival of spring. In literature, it appears as an image of transience and impermanence—snow falls but melts too quickly to blanket the landscape in white. Mizore often serves as a backdrop for human reflection on the passing of time, set against imperfect gray landscapes, which align with the aesthetic of wabi-sabi.

A haiku by Kobayashi Issa captures a scene featuring mizore:

霙降る 猫の子にまで 傘さして

(Mizore furu / neko no ko ni made / kasa sashite.)

“Snow mixed with rain falls—

even for the kitten

a parasol is given.”

This haiku is typical of Issa’s style, blending humor with tenderness toward nature. Mizore, an unpleasant weather condition one wouldn’t subject even a proverbial dog to (in this case, a kitten), becomes a backdrop for the care shown to the smallest and most vulnerable.

9. Neyuki (根雪) – “Rooted Snow”

On a practical level, neyuki is both a blessing and a challenge. It protects the soil from freezing, acting as a natural insulator, but also complicates daily life, requiring residents to be creative in dealing with winter. Homes in regions like Niigata, Aomori, and Yamagata are designed with steep roofs and specialized snow removal systems. Urban infrastructure often includes embedded heaters to melt snow on sidewalks and intersections.

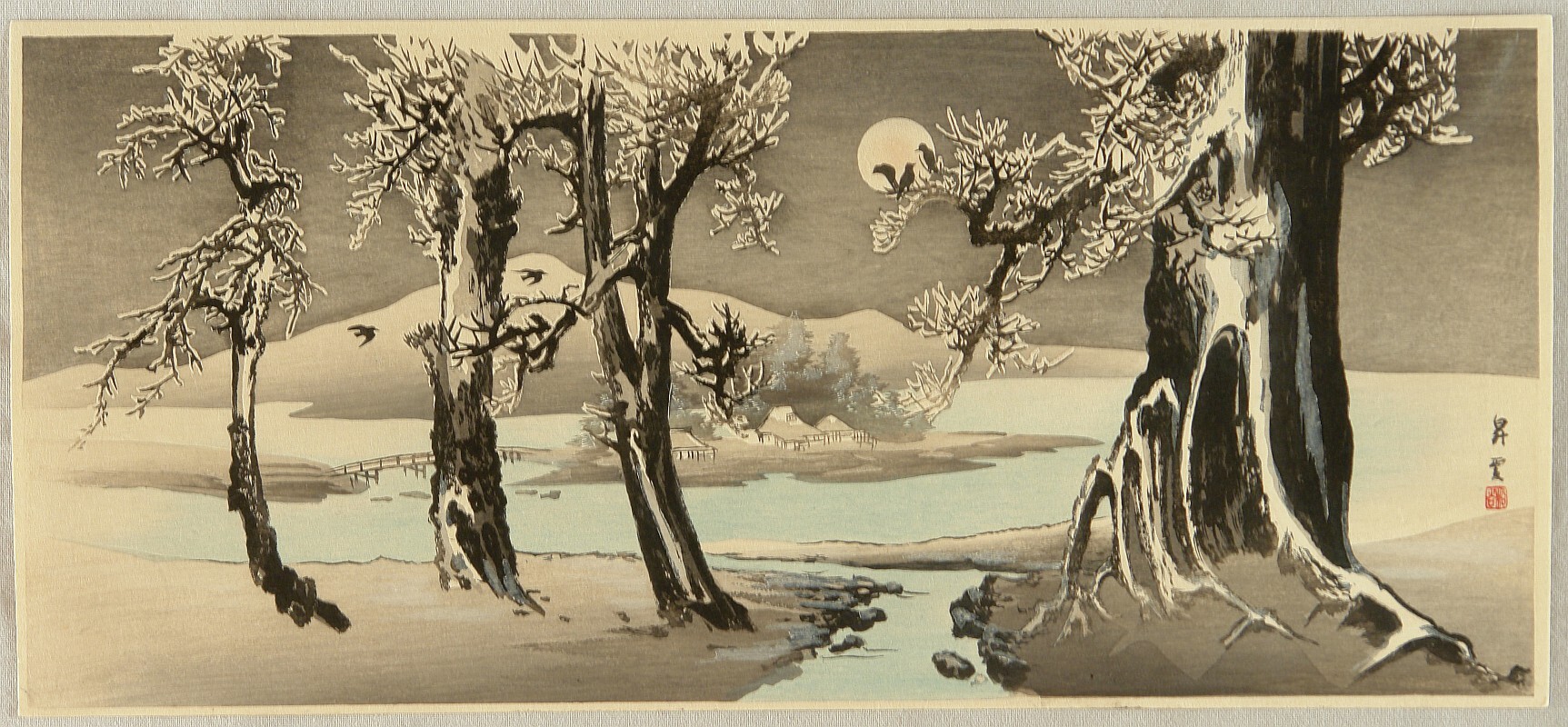

Neyuki, with its pervasive presence, shapes the lives of the villagers entirely, evident in the figures trudging through the snowy scene.

10. Yumegatari-yuki (夢語り雪) – “Snow That Tells Dreams”

Yumegatari-yuki (夢語り雪) is a literary term describing snow that seems to whisper dreams during quiet winter nights. The kanji 夢 (yume) means “dream” or “vision,” 語り (gatari) means “to tell” or “to whisper,” and 雪 (yuki) means “snow.” Together, they create an image of snow that not only blankets the earth in silence but also inspires the weaving of stories, as though nature itself is sharing its secrets.

Yumegatari-yuki refers to extraordinarily quiet and serene winter nights when the world is covered in a thick layer of snow, and all sounds are muted. In Japanese culture, such moments are times of reflection, meditation, and dreaming. This snow is associated with beauty but also with solitude and mystery.

Yamamoto Shōun’s woodblock print “Moon and Snow” captures the mysterious, almost surreal atmosphere of a winter night, perfectly embodying the concept of yumegatari-yuki—“snow that tells dreams.” The scene depicts solitary trees cloaked in a heavy layer of snow, illuminated by the pale light of the moon. The snow-laden branches seem to silently carry stories hidden within their icy crystals, while the soft glow of the moon enhances the aura of stillness and introspection. It is an image that seems to pause time—each element motionless, yet exuding an inner life, as if the snow truly whispers dreams of ephemeral beauty and the fragility of a winter’s night.

The minimalist scenery carries emotional depth. In Yamamoto’s work, snow is not merely a landscape element; it becomes a vehicle for a mysterious narrative, bridging the real world with the realm of imagination. The silence of the winter night, underscored by thick, snow-covered branches and the moon’s solitude, reminds us of fleeting moments that nature preserves in its memory. This is the essence of yumegatari-yuki—snow that inspires dreams, hides secrets, and creates a space for reflection on what is unseen yet profoundly felt. Yamamoto’s image is like a dreamscape where nature becomes both storyteller and listener.

Conclusion

The Japanese winter, especially in the harsh landscapes of yukiguni, serves as a reminder of how to live humbly before nature, yet in harmony with it. Beneath the burden of snow, both nature and humanity find ways to endure, grow, and discover beauty even in the most challenging moments. Snow—both symbolic and literal—teaches patience, resilience, and contemplation.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Yukiguni – What Life Lessons Can Be Learned from Japan’s Snow Country?

The Silence of Endless White – Winter Haiku as a Mirror of the Soul

Time Stood Still When I Looked at Hiroshige’s “Evening Snow in the Village of Kanbara”

Red Tears and Black Blood: The Modern Haiku of Ban’ya Natsuishi

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!