The Tradition of Kōans in Japan – A Zen Practice That Doesn’t Give Answers, But Takes Them Away

What do you hear when you clap with one hand? Why must you kill the Buddha when you meet him? Could the most important truth in spirituality be a tree outside the lecture hall? Who possesses the nature of a dog? Who is asking these questions?

The word kōan is written with the characters 公案 – literally: “public case.” Originally, it was a term from Chinese legal practice (gōng'àn), meaning a precedent – an official ruling one could refer to. But in Zen, a kōan does not rule – it disrupts. It derails patterns of thought that have taught us to seek answers, success, explanation. A kōan is not for understanding, but for experiencing – direct, non-conceptual, stripped of logos. That is why in Zen practice, “sitting in the question” is more important than knowing. Remaining ready. Remaining open.

What is a kōan?

The Japanese word kōan is written with two kanji characters: 公案.

The first – 公 (kō) – means “public,” “official,” “shared,” and sometimes “universal” or “belonging to all.” In ancient China and Japan, this character was used in the context of state, legal, or judicial matters.

Only later, within Chinese Chan Buddhism (which in Japan became known as Zen), the term acquired a new meaning: a spiritual task not to be solved, but to be experienced. The kōan became a vehicle for moving beyond the dualism of truth and falsehood, beyond conceptual thinking and beyond logic – not through negation of reason, but through its transcendence. What was once a legal matter became a matter of the soul.

In Zen practice, kōans are passed from master to student not to provide answers, but to lead to satori – a flash of inner understanding, an awakening that cannot be put into words. It is the difference between reading about rain and standing in the rain. Between the map and the actual terrain. A kōan does not aim to instruct, but to halt. Not to explain, but to shake – so that the mind, full of habits and customary judgments, pauses and falls silent for a moment, observing and experiencing.

In this sense, the kōan becomes a mirror. It reflects not what the world “is,” but how we see it. It reveals our attachments to language, logic, and identity. And when the mind tries to grasp the meaning of a kōan – such as “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” – it begins to see its own limits. Then something quiet may arise, barely perceptible – an intuitive understanding that is not thought, but presence.

That is why kōans have been used for centuries not to teach theory, but to unseat the student from habitual patterns of thinking. To open them to what cannot be captured in words. To awaken that part of us which understands without explanation – which knows, though it cannot say how.

Kōans in the History of Zen and Japanese Literature

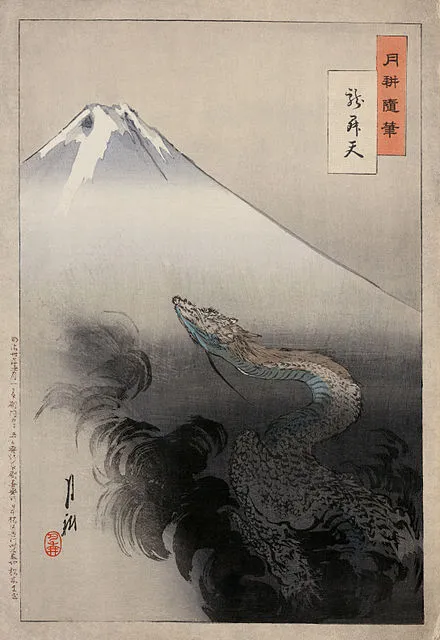

Kōans arrived in Japan with the spread of Zen Buddhism during the Kamakura period (1185–1333), a time when the country was caught in political turmoil, as the power of the first shogunal clans began to wane. Zen monasteries became spaces of inner order, discipline, and spiritual effort. Kōans took particularly strong root in the Rinzai school, where they became a fundamental tool of spiritual training. Masters gave kōans to students to provoke them into transcending habitual patterns of thought and encountering truth directly, beyond concepts. In the Sōtō school, kōans also played a role, though greater emphasis was placed on zazen – silent, “goalless” meditation.

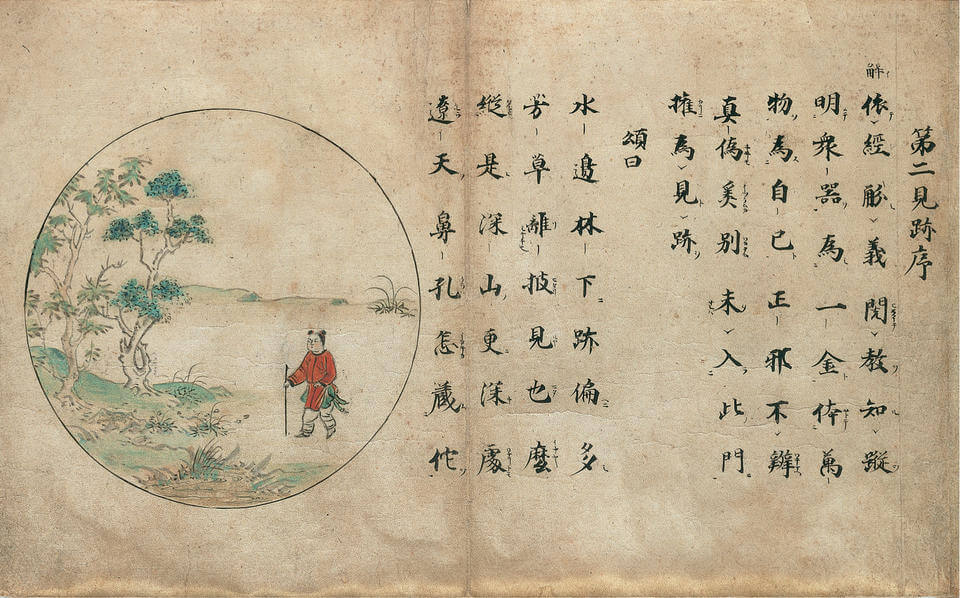

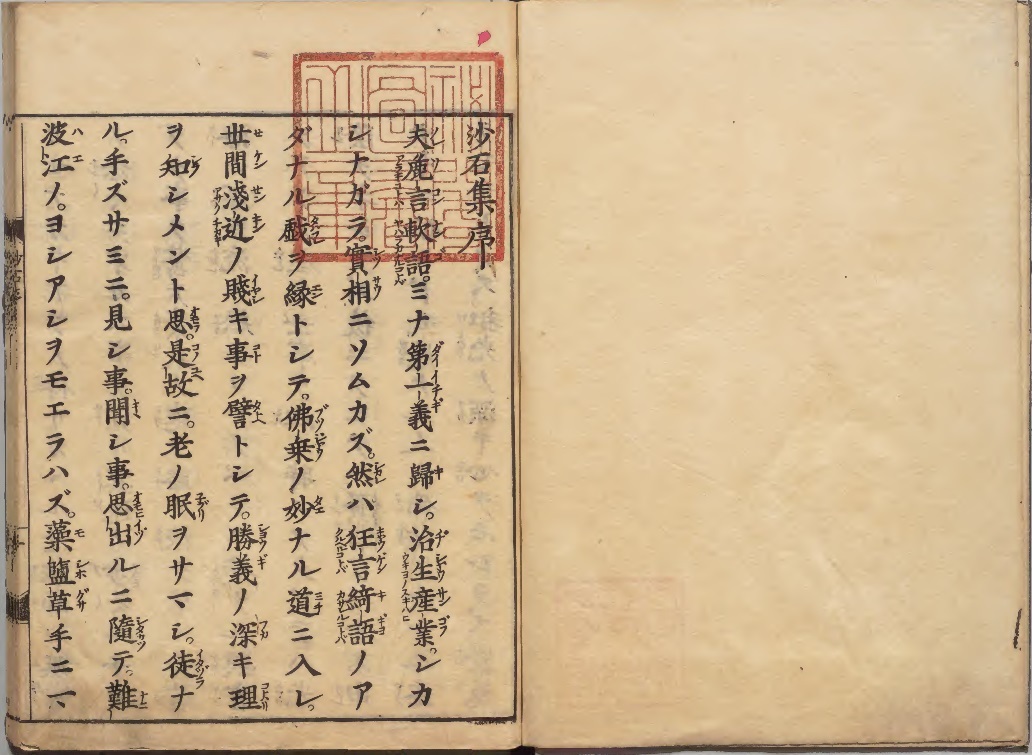

Shasekishū – even the title is metaphorical: stones are hard, enduring truths, while sand is the minutiae of everyday life, within which wisdom may also be found. It was not a philosophical treatise, but a literary collection of parables: about monks, spirits, ordinary people, miracles, and failures – each story meant to stir the soul, not to convince the mind.

In Japan, a kōan was no longer just a question from master to student. It became a question that anyone could pose to themselves – over a cup of sake or tea, during a walk, in the silence of everyday life. For Zen truth is not always hidden in a monastery – sometimes it waits in the reply: “Wash your bowl” (to which we shall return).

Why Do We Need a Kōan? On Opening the Mind

“If you meet the Buddha on the road — kill him.”

In Zen tradition, there is talk of a state of “great doubt” — daigidan (大疑団). This is not fear, not uncertainty. It is the courage to ask — and not receive an answer. It is the readiness to stand in the doorway and not enter, because first you must see whether the door truly exists. A kōan is a question that gives no peace. It doesn’t leave you with something to “understand,” but with something to experience. With a moment that is alive because it can no longer be tamed by the mind.

In Zen, it is said that everyday life is a kōan. When a young monk asked the master what he should do, he heard: “Have you eaten breakfast? Then wash your bowl.” There is no other teaching. Do not wait for something important to happen. Do not seek depth in distant words. Sometimes it is enough to truly notice the bowl — and yourself in the act of washing it.

Because a kōan does not ask: “What does this mean?”

Can we look without judging? Can we ask without needing an answer? Can we be in the world not to understand it, but to touch it — in wonder, in silence, in presence?

You do not need to be a monk, nor know Sanskrit or Chinese sutras. It is enough that you have the willingness to see the world differently than usual. And a kōan will help in this — not because it brings special arguments or reflections, but because it takes something away. For example… the illusion that we already know something.

Examples of Kōans

Mu! – Does a dog have the Buddha-nature?

– “Does a dog have the Buddha-nature or not?”

Jōshū answered with a single word:

– “Mu!” (“no” or “nothing”)

That’s all. Neither a lecture, nor a parable. Just this one word, spoken like the striking of a bell, whose echo continues to reverberate in the hearts and minds of practitioners for over a thousand years.

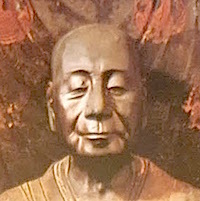

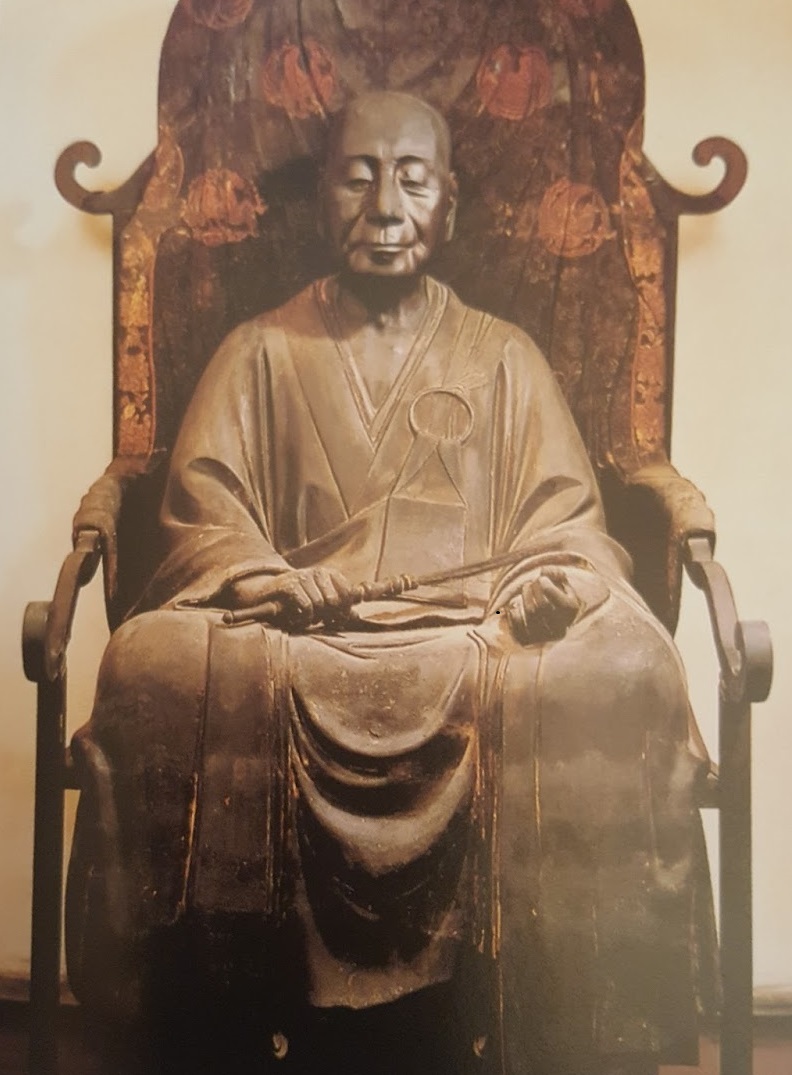

This kōan comes from the classical Chinese collection Wumenguan (Japanese: Mumonkan, “The Gateless Gate”), compiled in the 13th century by Master Wumen Huikai. Jōshū (Japanese: Jōshū Jūshin, died c. 897) was one of the most distinguished masters of the Chán school in China. His answer “Mu” — which literally means “no” or “nonexistence” — is considered the first and most important kōan in many transmission lines of the Rinzai Zen school in Japan. The question about the “Buddha-nature” refers to one of the core doctrines of Mahayana: that all beings — even a dog — possess the potential for enlightenment. So why does the master deny it?

Meaning

“Mu” is a gate to emptiness — to the space where all our notions, including spiritual ones, dissolve. The monk expects spiritual certainty, but instead receives emptiness that cannot be captured in words. For the Zen practitioner, “Mu” can become the center of meditation — a word not broken into syllables, but sat with, until all thoughts, reactions, and expectations are exhausted. When “Mu” becomes the only thing that remains — without explanation, without content, without context — then a flash of satori (awakening) may arise. Jōshū’s response is not meant to inform — it is meant to awaken.

In Life

Each of us asks ourselves questions in the form of “does this have value or not?” Am I good enough? Does what I do have meaning? Do others respect me? Is my daily life spiritual, or merely mundane? The answer “Mu” can be a blow to our ego — but also a call to live without labels. Instead of asking whether something “has” enlightenment, it may be better to ask: can I be present right now without needing to judge? Perhaps it is precisely then — in that simplicity, without confirmation — that we are closest to our own Buddha-nature. In practice, “Mu” is not a word — it is a state of mind. A space without “yes” and “no.”

What Are You Made Of? – He Gong!

“He Gong!”

Startled, she replied: “Yes?”

The master calmly asked: “Who answered?”

And in that one moment, in that sudden question without an answer, something more than conversation opened — a gate to the discovery of one’s true nature.

This kōan, known from the Korean Zen (Seon) tradition, is a variation of the classic question: “Who are you?” or “What is this?”, which appears in many schools of Mahayana Buddhism. This kōan is used as a direct impulse toward awakening — a living kōan, spoken not in a book, but in real encounter. Its core lies in the immediate confrontation with the question of identity, subjectivity, presence.

Meaning

“Who answered?” — this question cuts to the root of our certainty about the existence of a self. Is the “I” merely a name? A mind? A voice? A reaction? Buddhist philosophy has long questioned the existence of a permanent “I,” pointing out that identity is a construction — a collection of conditions, reactions, and memories. The question posed by the master is not meant to lead to a new definition of self, but to the recognition of the emptiness at the center of “I.” It is an invitation to transcend the ego — not by destroying it, but by seeing through the illusion that it is something fixed.

This kōan holds extraordinary spiritual power because it does not allow escape into concepts. It does not say: “Understand,” but rather: “Look — now.” In the moment we hear our name and react automatically, we forget to ask: who, really, just responded? When you say “yes?”, you do so out of habit — but is that reflex truly you? The master halts that motion. In her question lies the silent: wake up. Realize that your entire life is a series of responses — but have you ever truly examined who is responding?

In Life

In everyday life, too, we wear names, roles, and reactions. We are “husband,” “daughter,” “specialist,” “friend.” But what happens if someone calls us by name — and before we answer, we ask ourselves: who within me is about to respond? This does not mean one must live in constant detachment. On the contrary — it points to a fuller presence. To living not on autopilot, but from an authentic place. Sometimes the most important question is not “what should I do?” but “what am I made of?” — not as theory, but as a quiet discovery of what in you is true, before you name it “yourself.” In that one moment, you may touch emptiness — and feel that it is precisely what carries you.

The Cypress Tree in the Courtyard

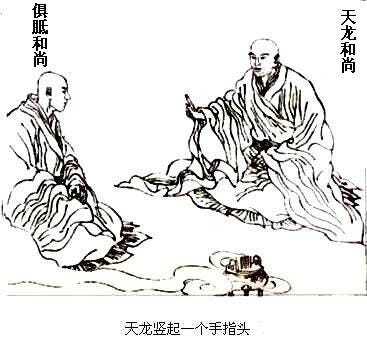

“What is the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the West?”

This question, in the Zen tradition, is a question about the essence of the teaching — about what the first Zen patriarch truly brought from India to China. The master could have delivered a lecture, cited sutras, pointed to the emptiness of existence. But instead, he answered:

“The cypress tree in the courtyard.”

And that was all. No more, no less.

This kōan comes from the collection Mumonkan (“The Gateless Gate”), and its author is Master Zhaozhou Congshen (Japanese: Jōshū Jūshin, 778–897), one of the most revered teachers of the Chinese Chán school. The question posed was a form of spiritual provocation: “How would you sum up the essence of Zen? What remains when we strip away all the ‘excess’ teachings?” Zhaozhou points to something concrete, tangible — a tree. But he does not do so arbitrarily. For the Zen student, it is a moment that either confuses or opens. This answer has intrigued, irritated, and inspired practitioners for centuries — and remains one of the most frequently interpreted kōans to this day.

Meaning

In spiritual practice, we often tend to seek “something more” — inner light, mystical experiences, proof of progress. The student asks what the master really brought from the East. He expects a spiritual essence. But the master says: “the tree.” This is a spiritual shift of center — from seeking to seeing. Zen encourages us not to overlook reality in the pursuit of interpreting it. In meditation, in breath, in an ordinary step — that is where the answer lies. Not in words, not in ideas — but in what is now. Perhaps it is precisely the cypress before the hall that shows the truth more than any teaching.

In Life

How many times in life do we ask: “What does it all mean?” We search for meaning, direction, depth. But perhaps it doesn’t always need to be sought. Perhaps sometimes it is enough to see the tree — truly see it. Without analyzing, without comparing. What is before us does not need to be explained to be full. When we ask great questions about our lives, our “why,” perhaps the answer will not come in the form of a motivational slogan, but in silence, in a small observation: “there is the sunlight on the leaves,” “there is steam rising from the tea.” Zhaozhou did not reject the student’s question — he dissolved it, showing that the teaching of Zen is life itself — in all its simplicity and extraordinariness.

Polishing a Brick – How to Become a Buddha?

– “Why do you practice zazen?”

– “Because I want to become a Buddha,” the student replied.

The master, instead of commenting, picked up a brick and began vigorously polishing it.

The student, surprised, asked: “What are you doing?”

The master replied: “I want to make a mirror out of it.”

The student burst out: “But you can’t make a mirror from a brick!”

To which the master calmly said: “And you won’t become a Buddha just by sitting.”

This kōan comes from the life of Master Nansen Fugan, a disciple of the great Mazu, and appears in classical Zen collections. It is one of those stories that dismantle the mechanical approach to spiritual practice — the belief that merely repeating the form is enough to attain enlightenment. In Japan, this story is often referenced particularly in the Sōtō school.

Meaning

Meaning

This kōan challenges the mistaken notion of practice as a means to an end. The student treats meditation like a production tool — I do something, therefore I will achieve something. But Zen is not a factory for enlightenment. It is not action that brings awakening, but a way of being. Mere sitting without inner transformation is like polishing a brick — it brings no light.

The master confronts the student with his attachment to form. He teaches that true practice is not action with the hope of a result, but full presence without expectation. Sitting in zazen is not a means — it is realization itself. But only when you are not sitting in order to obtain something — but to truly be.

In Life

In Life

In everyday life, we often “polish bricks” — we do things that look like growth, but are merely heartless rituals. We meditate because “we should.” We work on ourselves because “that’s what people do.” But perhaps it is sometimes worth stopping the chase for a goal and asking: does what I’m doing truly enrich my life — or am I just mechanically repeating something? A brick will not become a mirror. But we can — if we stop trying to be someone else, and allow ourselves to truly be who we are.

What Do Kōans Tell Us Today?

In the question, there is space. In uncertainty — a place where one can breathe. Can you sit with a sentence that cannot be resolved? Can you look at a tree without needing to name its species? Are you ready not to know — and in that “I don’t know,” be more present than ever before? The kōan does not invite us to win an intellectual game. It “wants” us to awaken to a life that already is — right now.

You don’t need to understand a kōan. It is enough to pause with it. To hear something that speaks beyond logic. And then to let it stay. Like the imprint of a foot on a path — proof that we were here.

Mujū Dōkyō did not write a textbook. He wrote a story about how to be. His Shasekishū is not a dry lecture — it is a collection of living stories: full of tenderness, absurdity, laughter, and sorrow. It is a book that does not moralize but shows us ourselves — in our mistakes, desires, and questions.

A parable can be a spiritual tool, but it can also be a gesture of care. For oneself — when you don’t know how to live. For others — when you want to say: “I understand.” For life — which sometimes needs us to stop fixing it and start listening.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Ikkyū Sōjun: The Zen Master Who Found Enlightenment in Pleasure Houses with a Bottle of Sake in Hand

Japanese Karesansui Garden is a Mirror in Which You Can See Yourself

Turn off the world. Step into the water. Furo

The Monk with the Naginata: The Martial Face of Buddhism in Kamakura Japan

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Meaning

Meaning In Life

In Life