Kokedama – A Tiny Moss Planet That Brings the Forest into Our Concrete Homes

A Living Jewel

What does the word “kokedama” mean?

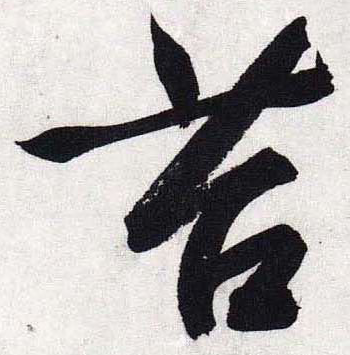

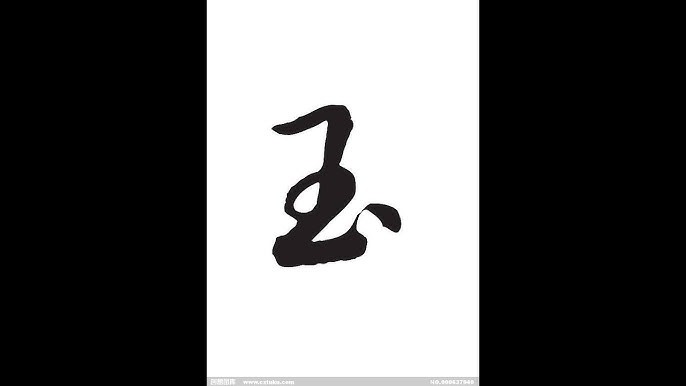

Starting with etymology, the Japanese word 苔玉 (kokedama) consists of two kanji characters:

- 苔 (koke) – means moss, but it is more than just a botanical description. Moss in Japanese culture has long symbolized time, patience, and the delicate beauty of aging. It is a plant without flowers or showy leaves, but one that enters into a subtle dialogue with stone, shadow, and moisture. In the wabi-sabi aesthetic, moss is practically its archetype — a living metaphor for the beauty of transience.

The combination of these two characters thus provides not only a literal description: “ball of moss,” but also a subtle metaphor: “green jewel,” “living sphere of nature,” “essence of tranquility.”

In practice, there are several ways to write the word kokedama:

- 苔玉 – the most common and formal form, using kanji characters

- コケ玉 – written in katakana, frequent in modern, aesthetic, or marketing contexts (e.g., on labels)

- 草玉 – a less common variant, literally “ball of plants,” sometimes used interchangeably when the kokedama is not covered in moss but other vegetation

It also happens that in colloquial speech the word kokedama is written entirely phonetically, without kanji, emphasizing its functional and contemporary popularity. Even in the phonetics of the word, there is something soothing — ko-ke-da-ma are syllables perceived in Japanese as soft, rhythmic, “lacking sharp edges.”

What is kokedama and how is it made

Kokedama can be placed on a flat surface — on a bed of stones, a ceramic saucer, a wooden board — or suspended in the air by a thread or string, becoming part of so-called hanging gardens — a sky garden full of light, floating spheres. In this suspended form, kokedama acquires an almost poetic dimension — as if hovering between earth and sky, swaying with the breath of the wind.

Once the moss or coconut fiber is carefully fitted to the shape of the ball, the whole is wrapped with natural string or thread — linen, cotton, sometimes hemp. Colored threads can be used to add a personal touch, or one may choose traditional white or subdued brown. Finally, if the kokedama is to hang, a supporting string is attached and its balance is checked. If it is to stand, it is enough to place it on a decorative dish, stones, or even a piece of wood — letting it appear as if it grew directly from tree or earth.

Kokedama is not an industrial product. Each is made by hand, with consideration for the specifics of a given plant — its size, weight, type of roots, moisture needs. This process can become a quiet ritual, repeated in silence or to the sounds of nature, reminding us that the work of the hands can also be the work of the heart. In this simplicity lies the secret of its charm — in the tactile feel of soil and moss, the attentive weaving of threads, and the shaping of life itself.

The History of Kokedama

Over time, the nearai technique evolved. Among bonsai enthusiasts, a movement arose in search of cheaper, more accessible forms — alternatives to expensive, handmade ceramic pots. From these ideas emerged what we now call kokedama. Initially, it was sometimes referred to as “bonsai for the poor” (binbō bonsai) — not in a derogatory sense, but rather with appreciation for its creative simplicity. Instead of a ceramic pot — a ball of earth; instead of a form imposed by a vessel — organic freedom. This minimalist alternative fit perfectly into the Japanese understanding of beauty — restrained, close to nature, focused on essence rather than outward appearance.

At the beginning of the 21st century, kokedama began gaining recognition outside Japan — initially among niche circles of florists, interior designers, and bonsai enthusiasts. A particularly significant role in its popularization was played by the Dutch artist and botanist Fedor Van der Valk, who created the concept of “string gardens” — gardens composed of kokedama suspended in the air, forming ethereal green compositions resembling a miniature universe. His works were exhibited in galleries and public spaces throughout Europe, and the media dubbed him “the creator of plant clouds.”

The history of kokedama is a tale of how ancient traditions can take on new form. It is a journey from bonsai techniques four centuries old, through the humble alternatives of impoverished garden masters, to contemporary galleries and homes where green moss balls become symbols of mindfulness, simplicity, and a return to what is real.

Kokedama – What Does It Mean?

Kokedama is a faithful expression of the wabi-sabi philosophy — one of the most important Japanese aesthetics. Wabi-sabi does not seek beauty in perfection or symmetry. It teaches us to see value in what is transient, what bears the marks of time, what is subtle and unassuming (more on that here: How to Stop Fighting Yourself at Every Turn? Wabi Sabi Is Not Interior Design but a Way of Life). The moss covering a kokedama is nothing more than life itself clinging to moisture and shadow. Over time, the moss may turn slightly brown, the soil may crack, the roots may break through the sphere — and this is precisely the point: beauty that does not strive to remain in artificial perfection.

Finally — the process of creating a kokedama is, in itself, ritualistic. Kneading the earth, selecting the right moss, wrapping the string tightly yet gently — this is not quick work. It requires presence. It requires attentiveness. That is why kokedama is often described as a form of meditation. In a culture where speed has become a measure of value, kokedama restores the value of slowness and focus. It becomes a daily ritual of care — not just for the plant, but for one’s own inner life. That is where its cultural and spiritual strength lies.

How to Begin Your Journey with Kokedama

Creating a kokedama requires neither a garden nor prior gardening experience. All it takes is a desire to make something with your own hands — something living, delicate, that not only decorates a space but also becomes part of a daily ritual of mindfulness. More and more people are choosing this form as an alternative to traditional potted plants, seeking not so much a decoration, but a way to connect with nature.

Where to Find Kokedama and Materials

Where to Find Kokedama and Materials

You can purchase a ready-made kokedama — at floral studios, plant boutiques, online shops with Japanese accessories, or simply in well-stocked garden centers. Some places offer made-to-order compositions, allowing you to choose the specific plant, type of string, and even the style of presentation — from classic moss balls to more modern suspended forms or those placed in vessels.

For those who wish to try their hand at making one, DIY kits are also available — containing the appropriate soil mix, dried moss, string, and step-by-step instructions. But even without special kits, you can gather the necessary components on your own — peat, akadama clay (or a substitute), moss (or coconut fiber), cotton string, and of course, a plant.

Learning to Create – From Workshops to Quiet Evenings Alone

Learning to Create – From Workshops to Quiet Evenings Alone

Learning to create kokedama can be an enjoyable process — almost meditative. One can start by attending a workshop. In-person courses are increasingly held in botanical gardens, cultural centers, or plant galleries, especially in large cities. Online workshops are also growing in popularity — with kits shipped in advance and live sessions guided by an experienced instructor, who walks participants through the entire process step by step.

Plants That Love Kokedama

It’s better to avoid plants with very extensive, delicate, or brittle roots — such as rosemary, eucalyptus, or certain orchids with large pseudobulbs. Likewise, plants that grow too large or too fast may deform the ball and present care challenges. It's best to start with low-maintenance species and only later experiment with more demanding ones.

Kokedama Styles – The Many Faces of One Form

Increasingly, however, versions wrapped in coconut fiber are appearing — especially practical in urban environments, where access to natural moss is limited. This texture adds a bit of wildness, a raw character to the composition.

The so-called “string garden” — a hanging kokedama garden — is also gaining popularity. These gardens consist of kokedama suspended at varying heights, creating not only an aesthetic effect but an almost dreamlike one — floating green spheres that resemble planets suspended in a tranquil domestic universe. Others prefer more “grounded” forms: kokedama placed on stone trays, in glass vessels, or on wooden coasters. Each of these arrangements gives the plant a new context — it can be the focal point of a room, a subtle detail, or a living amulet by the entrance to a home.

To begin the kokedama journey is, in truth, to invite a ritual into your life — a simple, down-to-earth, calm, and quiet ritual. A ritual in which our hands shape a space for life, and life — with all its persistence — responds by growing.

How to Care for a Kokedama

Watering is most often done by submerging the entire ball in a bowl of lukewarm, soft water (preferably filtered or rainwater) for about 10–15 minutes (though not all plant types like this — it's important to check!). This is usually done once a week, though in the summer or in heated rooms, watering every 3–4 days may be necessary. A helpful indicator is the weight of the kokedama — if it feels light, it likely needs water. Another sign is the color of the moss: if it’s too pale, dry, or brittle, the kokedama is probably dehydrated.

Lighting should be bright but diffused. Kokedama does best near eastern or northern windows, or behind a sheer curtain on southern exposures. Direct southern sun can damage the leaves and dry out the moss, while placing it above a radiator or near heat sources leads to rapid drying of the root ball.

Fertilization is also done through “bathing” — simply add a few drops of liquid fertilizer to the water used for soaking. This is usually done every 3–4 weeks during the plant’s growing season (spring–summer); in winter, fertilization should be reduced or stopped altogether.

Kokedama – Everyday Well-Being

Made entirely from natural materials — soil, moss, string, and roots — kokedama places no burden on the environment. Its life cycle aligns with the rhythm of nature: it produces no waste, requires no plastic, and after years can return to the earth without a trace. Moreover, properly chosen plants — such as ferns, Epipremnum, or dracaenas — help purify the air, absorbing toxins and releasing oxygen, acting as small, biological air filters for the home.

But it’s not just the body that benefits. Equally important — if not more so — is kokedama’s effect on the mind. Its care teaches patience, tenderness, and presence. Daily watering, pruning, observing — these small gestures can become a form of quiet meditation, a return to oneself amid the noise of everyday life. Contact with the plant, the touch of moss, the rhythmic winding of string — all of it slows down time, quiets the mind, and reminds us that life doesn’t need to be fast to be full.

Kokedama is a gesture of care — for the plant, for the space, for ourselves. It is a way to let a fragment of the forest come live with us at home.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Japanese Flower Dictionary – 15 Extraordinary Flowers and Their Symbolism in Japanese Culture

Understanding the Kanji “sakura” (櫻) – the cherry blossom as a way of seeing the world

Ikebana: The Japanese Art of Speaking in Flowers

Hanami – April Day of Reflection on What You Have Now, Which Will Pass and Not Return

Goshin "Guardian of the Spirit" – Bonsai as a Forest in a Pot Telling of Life, Family, and Nature

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Where to Find Kokedama and Materials

Where to Find Kokedama and Materials