The Man of Brass and Stars – How the Brilliant Inventor Hisashige Tanaka Thrust Samurai Japan into Modernity

The Man Who Was a Vehicle of the Future

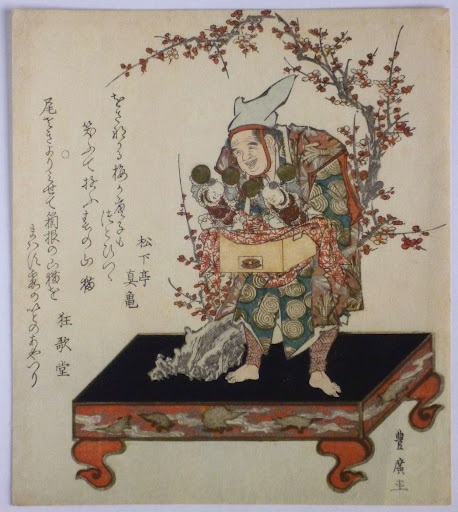

But the talents of Hisashige Tanaka did not stop at the fairground stages of Edo. In his workshop in Fushimi, he received astrologers of the Tsuchimikado clan—the guardians of the imperial calendar—to collaborate on mechanical designs that could measure time. From this alchemy emerged the shumisengi: a cosmological clock in which a miniature sun and moon danced around the copper Mount Shumisen, marking Buddhist eras with the punctuality of a gong. Meanwhile, outside the windows, young rōnin shouted sonnō jōi, rumors of the Black Ships drifted through the air, and Tanaka—a man of blood and brass—felt that the universe he had managed to enclose within a clock was now cracking open above the rooftops of Kyōto.

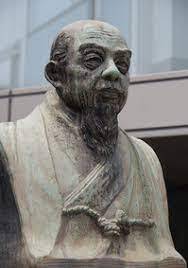

Who Was Hisashige Tanaka?

He created dolls that wept with emotion, clocks that struck not just the hours but the very meaning of existence, lamps brighter than any daimyo’s candles, and eventually, machines that would transform Japan. Without degrees, without university, without government support—a self-taught dreamer who rose from ancient Fukuoka toward the future, taking the first steps down a path later followed by giants like Toshiba. But before industry was born, before the telegraph and steam arrived—there was a boy who did not want to inherit his father’s workshop. He wanted to remake the world from scratch. Let us now come closer to his life.

The Life of Hisashige Tanaka

Kurume, 1799–1819

A Childhood in a Turtle Shell Workshop

In the evenings, after the rest of the household had gone to sleep, he would pull from the corner a granite inkstone, mysterious screws, and a piece of dyed cord. From these scraps, he created a miniature box—“a stone inkstone chest with a secret lock.” One had to twist the cord in a precisely designated way to hear a soft click and open the lid. When he brought it the next day to his terakoya (more about Edo-era schools here: Terakoya Schools for the Children of Ordinary People in the Time of the Shogunate – There Are Still Things We Can Learn From Them in the 21st Century), the history teacher tried his luck, then the whole class, and finally the abbot of the neighboring temple; no one succeeded. In the eyes of his peers, Hisa felt for the first time a flash of awe—more addictive than the scent of polished shell.

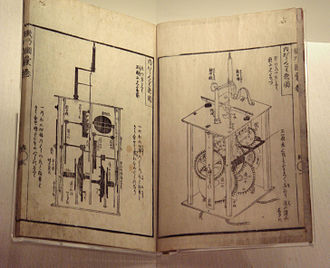

Discipline at school was strict: calligraphy in seiza position, cold reed canes for every crooked brushstroke, mechanical recitations of the “Analects.” But in a library cabinet, protected from Kyushu’s moisture, lay a freshly imported copy of the Karakuri-zui—an illustrated treatise on mechanical marvels (more on karakuri ningyō dolls here: Karakuri Ningyō of Ancient Japan – Wooden Mechanical Robots That Served Tea, Danced, and Wrote). For most students, it was just a series of strange drawings of gears; for Hisashige, it became a map to a world where the spirit of bamboo dolls came to life through the quiet workings of a spring. While the calligraphy master drew neat rectangles of kanji, the boy in his imagination was already building miniature catapults, rice self-scooping spoons, and dolls that could bow and brew tea.

At night, walking along the path beside the rice fields, the clatter of Hisa’s sandals echoed with imagined ticking of clocks rather than cicadas. He dreamed of machines that could count the stars, of dolls that could write poetry, of lamps so bright they could illuminate the darkest corner of a street. And perhaps it was then, walking in the glow of fireflies, that he decided he would not become a master of shell—he would become a master of motion. Thus began the journey of a boy who wanted to rewrite the world in the language of gears and springs, not yet suspecting that his first step would echo into the age of steam and telegraphs.

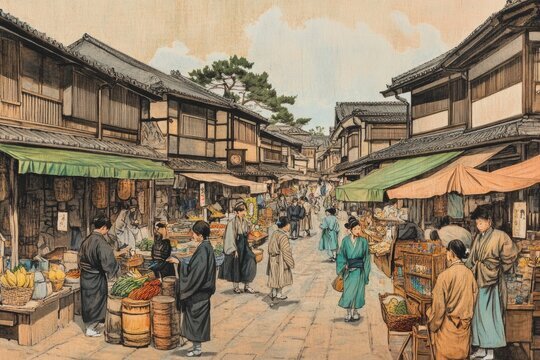

1820–1833 MArketpalces and Celebrations

The Wandering Genius of Karakuri

He traveled without pause, from province to province, like a wandering monk—but instead of sutras, he carried faith in moving gears. Every night, before falling asleep on a raised bed in a roadside inn, he would dismantle his dolls, oil their tiny bearings, and listen to the metallic whisper beneath his fingertips—as though checking the pulse of his own dreams.

Osaka, 1834–1836

Pragmatist in the City of Merchants

The fashion for karakuri performances, however, began to wane like the wick of a used candle. The crowds that had left handfuls of coins in Edo expected something more practical than the bow of a painted boy in Osaka. The merchant world of the Dōjima district calculated everything in the neat columns of the abacus: cost of materials, fire risk, price of light. Hisashige sensed the shift in the wind—this was no longer a time for theatrical emotions, but for practical marvels.

Despite a certain success, at night—when the chatter of teahouses faded and distant bon-odori drums moaned from the direction of Sumiyoshi—he still heard in his mind the soft “click” of his first little box. He knew that lamps and candlesticks were only the vestibule of the world of invention; already, far more ambitious plans circled in his thoughts. The world was about to spin faster, and he—the son of a turtle-shell craftsman—intended to give that motion the rhythm of ticking gears.

Kyōto / Fushimi, 1837–1853

Clocks, Calendar, and Cosmos

Astrologers from the Tsuchimikado clan—the guardians of the imperial calendar—regularly visited Tanaka in his Fushimi workshop. Dressed in silk robes the color of clouds, they brought scrolls covered with charts of planetary, lunar, and stellar motion. Their knowledge—rooted in centuries-old calendrical tradition—collided with Tanaka’s mechanics and precision, creating a unique dialogue between ancient cosmology and modern engineering. Over bowls of green tea, they debated with Tanaka: did the sun truly need to follow the ecliptic, or could there be a more elegant Western way of measuring time?

In the evenings, Tanaka would visit Shinto scholars, who viewed the invention as a kind of technical prayer; in the mornings, he debated theories of Nieuwenhuis with Dutch physicians in merchant residences. But the city pulsed with increasing violence: young rōnin shouting sonnō jōi (more on this here: The Republic of Ezo – A One-of-a-Kind Samurai Democracy) smashed the windows of foreign goods shops. Rumors swirled of black ships and ghostly men in leather shoes. Tanaka, a man of blood and brass, felt that the cosmos he had managed to enclose in a clock was now beginning to open and fracture just above the rooftops of Kyōto.

Saga, 1854–1863

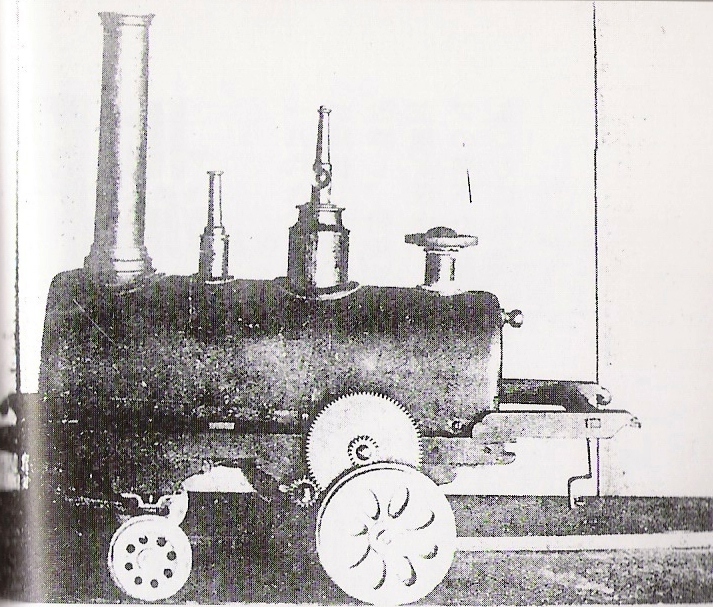

Steam, Steel, and the First Locomotive

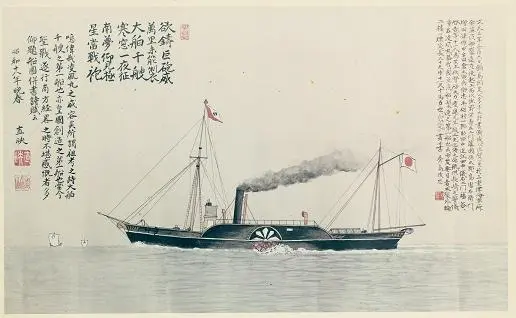

There was no time for awe: in the workshop, he was simultaneously sketching the plans for the steamship Ryōfu-maru, the design of a portable telegraph, and notes on a flexible wire for signal transmission. Tanaka absorbed everything, flipping through the pages of Dutch books: the impact force of a piston, the length of a rocker arm, the secret of a thread that could withstand the greatest pressure.

In the winter of 1863, when frost made the snow on the castle roofs crackle, the first steel cannon barrel emerged from the furnace; on the test range, the roar tore through the silence of the rice fields, and the echo carried all the way to Ariake Bay. Tanaka stared into the smoke and saw not just a cannon, but a distant horizon—a nation that would soon need all the power of steam and electricity to survive the storm of foreign fleets. The samurai lowered their swords in a gesture of respect, and he, trembling from exhaustion, instead of resting, opened another sketchbook: the future ticked in his mind like a clock that could not be stopped.

Kurume, 1864–1872

Return Home and Weapons of a New Era

During those years, he took in a boy with keen eyes, the son of a local goldsmith. Daikichi, later known as Hisashige II, observed his stepfather in silence, handing him files and pliers, just as young Hisa had once passed them to his own father. Amid the clatter of hammers and the creak of springs, not only weapons were born, but a legacy: Tanaka already knew that the clock of the future could not stop with his final breath. It had to keep ticking.

Tokyo, Meiji 1873–1881

Telegrams from Ginza

The days passed to the rhythm of Morse signals: ton-ton-tsū (“tick tick tiiiick”)—silver sparks leapt between contacts, and Tanaka recorded the vibrations in a small notebook. At night he laid out brass tubes, receivers with parchment membranes, and experimented with a voice trapped in wire—a telephone prototype that chirped like a cricket. In another corner of the workshop, a hōji-ki was taking shape—a mechanism designed to transmit time signals (jihō 時報) directly to government offices and railway stations; the main spring coiled with a soft click, as if an invisible clock of Japan ticked inside.

Outside, Ginza blazed with gas lamps, ricksha drivers in gleaming happi jackets called to customers, and telegraph wires sang in foreign tongues cast across the ocean. Tanaka, hunched over his latest spring, once again listened to the hum: he knew that every spark in a copper wire was one more step toward the world he had dreamed of as the boy with the secret box. When his heart stopped beating on November 7, 1881, the clocks in his workshop still ticked quietly with the same rhythm. Outside, the ring of ricksha bells already echoed like the fanfare of a new era, and telegraph wires carried a name that would soon grow into legend—Toshiba.

The Legacy That Became a Corporation

From Tanaka to Toshiba

In 1939, Shibaura merged with Tokyo Denki, a specialist in incandescent lamps originating from Hakunetsu-sha, a pioneer of electric lighting in Japan. From this union was born Tokyo Shibaura Denki—a name soon shortened by employees and clients alike to the softer-sounding Toshiba (東芝, combining the characters “Tō” for Tokyo and “Shiba” for Shibaura).

The postwar decades brought rapid development: from Japan’s first washing machines and televisions, to nuclear reactors and large-scale power systems, and eventually semiconductors and laptops that brought the Toshiba brand into millions of homes in the 1990s. However, the 20th century ended with a series of turbulences, and the 21st fared no better: the collapse of Westinghouse, a major accounting scandal (2015), and a forced sale of several divisions.

The new leadership is focused on green transformation technologies—steam turbines for hydrogen power plants, SCiB lithium-ion battery storage systems, and silicon carbide semiconductors developed in collaboration with automotive industry partners. Simultaneously, research is underway on quantum photonics in laboratories in Cambridge and Kawasaki, conducted under the motto: “creating things that do not exist.”

Thus, the spring once set in motion by the hand of Karakuri Giemon still ticks—today in server rooms powering smart energy grids and inside magnetic trains. Whatever the next century brings, every impulse running through Toshiba’s copper wires is an echo of the secret box that eight-year-old Hisashige Tanaka once opened amid the scent of turtle shell.

The Masterpieces on Which Japan Climbed Toward Modernity

At a time when most clocks measured European linear time, Tanaka created the shumisengi, a clock that accounted for the unequal lengths of Japanese hours through the seasons—a tribute to the cosmic order of the Buddhist universe (more about timekeeping in Tokugawa Japan here: The Hour of the Rat, the Koku of the Tiger – How Was Time Measured in Shogunate-Era Japan?). His mannen-jimeishō was not merely a mechanical calendar—it was a philosophical treatise cast in metal. Every one of his inventions, even something as modest as the makura-dokei (pillow clock), had both function and soul.

When the era of steam and steel arrived, he did not hesitate. He built Japan’s first steam locomotive, founded a cannon foundry, and contributed to military modernization. But shortly thereafter, he returned once again to tools of peace: telephone prototypes, domestically manufactured light bulbs, electricity-free refrigerators, rickshaws, irrigation pumps, and bicycles. It seemed there was no object of daily life that Tanaka would not try to make more human.

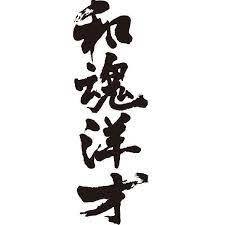

Philosophy of Work and the Spirit of Modern Japan

Tanaka embodied the Meiji no seishin—the spirit of the Meiji era. He didn’t wait for modernization to come to him. He invented it himself, step by step, screw by screw. He was not a politician, nor a general. He was a master who turned his workshop into a forge of the future.

And perhaps that is precisely why his story has endured. Because it is not a tale of triumph over others, but of the victory of imagination over time. Because every clicking gear in his machines was the quiet voice of Japan learning to speak a new language—without losing its own soul.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

An Hour of Complete Focus – What Can We Learn from Traditional Japanese Craftsmen, the Shokunin?

Iemoto – The Japanese Master-Disciple System That Has Endured Since the Shogunate Era

Machiya: What Were the Townhouses of Edo Like? – The Lives of Ordinary People During the Shogunate

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!