The Invisible Woman – Life as a Samurai’s Wife

Solitude more as a role than a feeling

A Day in the Life of a Samurai’s Wife

Her husband, Hirata Atsutane, had left yesterday at dawn to visit a local official, and she—as always—remained. She guarded the house. She kept watch. She waited. Waiting was her specialty. She waited for news from Edo, for a letter from her stepdaughter, for permission to take a walk alone to the temple. She even waited for the rain—for only then did she feel nature spoke to her in the same language it once had, back in the city. In Edo, the rain smelled different.

She reached for the brush. In letters, she could be herself. She did not have to remain silent. She wrote to her stepdaughter in Edo, using precise, elegant calligraphy that was her personal act of resistance against disappearing. The ink absorbed her thoughts. “Yesterday, I dreamed of your mother. We sat together by the fire. She told me she missed the scent of apricots. Are they already blooming in your garden?”

That day taught her everything. To remain silent. To smile when she had no strength. To make sure the tea tasted just right, that her husband’s kimono had not the slightest crease, that conversation with an unexpected guest did not betray her fatigue. Day after day, in the shadow of the sword that hung in the alcove, Orise cultivated a quiet, feminine kind of courage.

She would do it again today. She would compose a letter. She would instruct the maid to pack dried fruits for shipment. She would sew a button on her husband’s ceremonial attire. And when dusk came and all fell silent, she would light a single oil lamp and write down who visited the house, what was discussed, what Atsutane ate. The journal was her responsibility—and her only way of remaining “visible”…?

She was a samurai’s wife. But she was also something more. A memory. A guardian. A shadow, without which light would have no meaning.

The Voice of Orise: Solitude, Frustration, Tenderness, the Everyday

It was then that Orise began to write letters.

In one letter, she mentions how much she misses books. She asks for textbooks for girls, because there are none in Akita, and she wants to pass something on to younger women. She understood that knowledge, words—even the humblest—could be a shield. Writing was, for her, resistance against disappearance—proof that she existed, that she thought, that she felt. Her calligraphy—gentle, attentive—was like breath on paper. A true presence in a world that demanded her to be a shadow.

Orise’s love for Atsutane was not romantic in the Western sense. It was a deep bond grounded in the sharing of fate. When he wrote treatises, she ensured he had fresh ink. When he went to officials, she watched over the home, the guests, the memory. She was his shadow, but also his pillar. Without her, his life in Akita could not have functioned. And yet history has remembered primarily him.

Orise died in 1846, twenty-two years before the end of the Tokugawa era. Her letters survived. They are not loud, not revolutionary. But they are true. They are the record of a woman’s existence that needed no sword to be worthy of remembrance. Let us now see what they can teach us about the lives of women in the samurai class during the Edo period.

Who was a samurai’s wife?

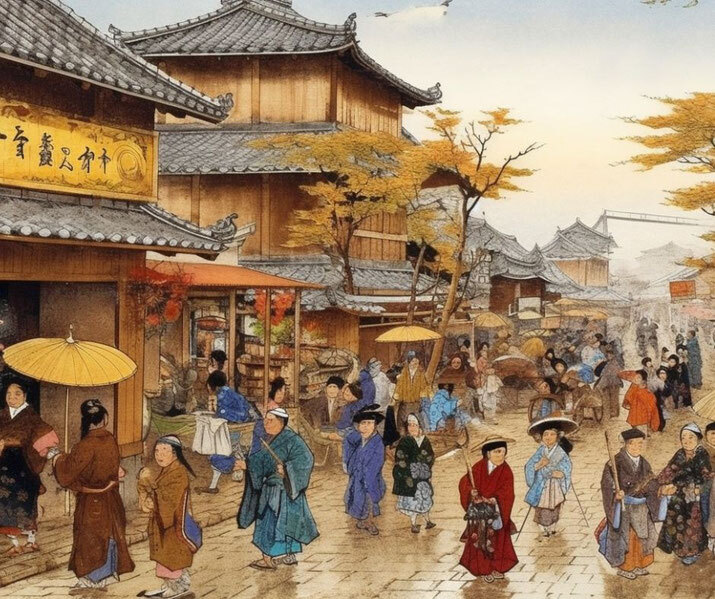

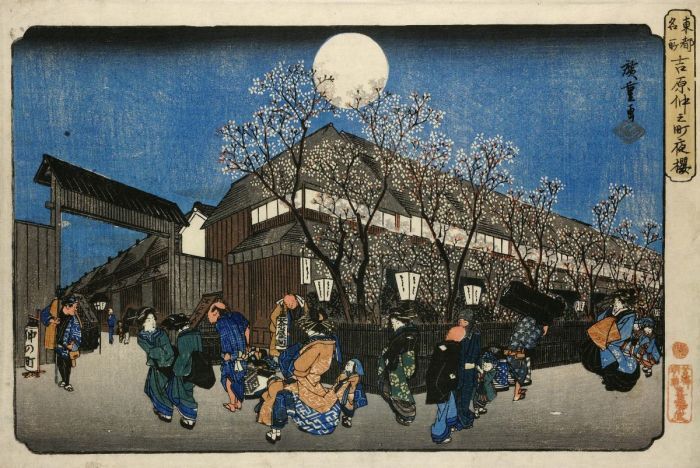

Unlike peasant women (nōfu no onna), who worked in the fields from dawn to dusk with hands submerged in the mud of rice paddies, or merchant-class women (chōnin no onna), who ran family shops, sold tea, wove silk, or baked red bean confections, the wife of a samurai lived in a closed world, full of rules, silence, and ceremonial obligations. Merchant daughters could go to the market, haggle with suppliers, stroll through temple festivals, or attend performances by street entertainers. The wife of a samurai could not leave the house alone—if she did go out, it was only in a palanquin (norimono) and always accompanied, most often by a maid.

Though invisible to the world, she was the heart of the household—its memory, its ritual, its endurance. In the genealogies (kafu) compiled by the daimyō, women did not appear as individuals, but as “daughters of so-and-so,” “wives of so-and-so,” yet without them, there could be no marriage, no adoption of an heir, no continuity of the lineage. It was women like Hirata Orise who kept the hearth burning, sent letters to stepdaughters, meticulously maintained household chronicles, and ensured that the offerings before the butsudan (the domestic Buddhist altar) had the proper scent and shape.

But in practice, these women did far more than bear children. They taught etiquette, ensured their husbands looked presentable during audiences, mended kimono, sewed ceremonial obi sashes, cooked dishes that would not offend refined palates, managed relations with extended family, arranged gifts, wrote letters, tended the ill. And they endured—lonely, excluded from public life, yet responsible for ensuring that the man who wore two swords (The Etiquette of Samurai Weaponry – When the Steel of the Katana and a Subtle Gesture Spoke in Silence) did not forget who he was.

In a society governed by the principles of giri (duty) and on (gratitude), the samurai woman was the living embodiment of both. She was not the heroine of the tale, but without her, no tale could begin. She was like ink on tracing paper—not visible by itself, but making everything else permanent.

Home, Ritual, Silence – The Everyday

A woman in a samurai family could not leave the house of her own will. If she had to go to a temple or visit relatives for a holiday, she traveled in a norimono—a palanquin—accompanied by a servant or a male family member. Even shopping—mundane and everyday—was not her domain. In a letter, Hirata Orise laments that her servant was unable to bring back the right ingredients from the market, but she had no right to do it herself. “I have no access to what I know and choose myself. The taste of Edo is unreachable here,” she wrote to her stepdaughter.

Sewing and garment care also rested on her shoulders. A samurai’s kimono had to be impeccable, especially during an audience with a local official or a ceremony at the castle. Orise recalls how she consulted her husband’s sister on the details of his attire for a visit to the daimyō. A missing embroidery or a shade of obi that was too dark could be interpreted as a sign of disrespect toward one’s status—and she would be held accountable. In a samurai house, a woman did not simply mend—she shaped the representative appearance of the entire family.

When Atsutane went to offices, temples, or visited his students, Orise acted as his representative. She could not leave, but she could receive guests, serve them tea, conduct conversation according to etiquette, and above all—ensure the home was ready for any visit, at any time. Guests could arrive unannounced—since there were no telephones—and a hostess’s obligation to uphold decorum allowed no exceptions, regardless of the hour. Thus, any moment could suddenly become a formal reception—and Orise, like other women of her position, had to be perpetually prepared.

Thus, the home was not so much a place of confinement as a stage of duty. Every gesture—from the placement of dishes to the phrasing of a letter—was part of a quiet, precise ceremonial of continuity. In an era when a samurai rarely had the chance to prove his courage on the battlefield, it was the woman who made his life something worth defending.

In silence and shadow, between the kitchen and the altar, between the journal and the tea box, the woman of a samurai household built the endurance of the family line. Without leaving the house—she moved its heart.

義理 (giri) – Duty Above Love

In Edo-period Japan, marriage was rarely an intimate union between two individuals (at least not in the samurai class). More often, it was a precisely planned move in a game where the stakes were stability and power. A samurai could not marry a woman from outside his class without official approval and often—as in Orise’s case—the bride-to-be had to first be formally adopted into another samurai family so that her origins would not tarnish her future husband’s reputation. Orise, the daughter of a master tofu maker, was adopted into the family of an influential rural official before the marriage—not to change her life, but to preserve Atsutane’s status.

In samurai households, where strict primogeniture was practiced (meaning everything passed to the eldest son), the absence of a son did not necessarily mean the end of a lineage—as long as there was a woman who could lead the family through the threshold of death. The widow not only managed the house after the husband’s passing, but made decisions on his behalf, chose adoptive heirs, and continued the ancestral rituals. She—not an official, not a cousin—often decided who would become the next head of the family. In this way, she became more than a wife—she was like the foundation for the next floor of the house, built of names and merit.

Love in this world had a different face. It was not rebellion against duty—it was embedded within it but had to fit inside its frame. Orise loved Atsutane not only as a husband, but as the central point of a structure of which she was the bedrock. Her affection was not expressed in the words “I love you,” but in care, in strategy, in loyalty that did not seek reciprocation—only survival.

The widow in a samurai family was not helpless or left alone—she was the central pillar in the space left by the man. Her presence did not vanish—it became even more visible, though still silent. In a culture that taught a woman should be like a shadow—it was that very shadow that shielded the past, the future, and the present of the ie.

Perhaps the fullest image of this strength is the fact that it was not the sons, but the women of the Hirata family who, for decades, preserved the memory of Atsutane—his legacy, his students, his lineage. Quietly, wisely, effectively. Just as samurai women had done for generations.

What is the life of an invisible shadow and pillar?

The life of a samurai’s wife—like Orise’s life—unfolded under constant and judging observation: by her husband’s relatives, household members, neighbors, society. Every gesture, every word, even every decision about what to cook and when to write a letter was immersed in a dense network of expectations. A woman of that era was to be quiet, obedient, modest, attentive—but at the same time effective, representative, responsible for the continuity of the family. Today’s psychologists might describe this as a high level of internalized social norms—a woman required no external oversight, for the norms that controlled her lived within her. Others’ expectations became her identity and filled her completely. Although... perhaps not entirely?

And in that role emerge longing, frustration, pride, calm, and melancholy—feelings that today we might associate with “ambivalent dependence” or “frozen emotionality.” Orise’s longing for Edo—for the life where she could walk, visit temples, laugh with relatives—was not expressed directly, but it spread into the margins of her letters. She wrote of the lack of books, of how in Akita “there are no texts for girls,” and that “a soul without literature is like a pond without water.” This short, seemingly neutral sentence reveals a spiritual hunger.

And yet all of this was cloaked in melancholy—a state we might today liken to gentle existential depression, born from the tension between one’s inner life and one’s outer role. Orise had no place to express doubt or sadness—so she conveyed them through sensory details: she missed the smells of Edo, the right taste of soup, conversation. It was the loss of the everyday world—she felt “uprooted.”

And still—she endured. In silence, in her letters, in her journal. She endured in loyalty that solitude could not undo. She endured because she was needed, even if no one ever told her so.

The image of the “charming Japanese woman”—smiling, polite, delicate—is an aesthetic projection, not a psychological truth. Orise, like many women of her era, was a powerful pillar of her household clothed in fine silk. Her softness was a choice, not a weakness. Her silence was an act—not an absence of voice, but a deliberate way of using it.

The Legacy of the Invisible

What remained were letters—like those written by Hirata Orise—which carried through generations more than words: a posture, a tone, an inner discipline. What remained were entries in family journals, neat script from a woman’s hand, where names, visits, and duties blended with the quiet voice of story. What remained were rituals—like the daily lighting of incense before the butsudan, like the preparation of a tea box as a summer gift for a cousin from another branch of the family. In these gestures—repeated by daughters, daughters-in-law, granddaughters—there lived something no one ever named as heroism.

Only today are we beginning to reclaim their voices. Newly rediscovered letters, diaries, domestic records—like those kept by Orise—reveal the psychological and spiritual worlds of women who for centuries endured in the shadow of the sword’s ethos. Their story is beginning to return—not as a footnote to male narratives, but as a fully valid current of history. They were not merely wives of warriors—they were warriors of another front, equally essential, masters of survival in a world that gave them no battlefield and yet demanded they fight one every day.

Samurai womanhood endured as an archetype of loyalty without voice, strength without violence, presence without recognition. There is something deeply modern in it: an echo of women today who carry the weight of structures that do not see them, who care for the world though they are absent from lists of the celebrated.

Was the life of a samurai woman a cage? From today’s perspective—yes. But it was a cage in which gardens grew, despite captivity. A cage in which souls were tempered. It was a form—rigid, confining—but within it, samurai women carved out their strength: in patience, in ritual, in tenderness toward the everyday. Still—it was a cage.

Their story tells us that the world does not rest on the shoulders of those who charge with swords in hand, but on those who know how to endure. Without applause, without weapons, without legend. And yet—unconquered.

A Final Note

During the Edo period, even women from lower classes in Japan were taught to read and write. They attended terakoya schools, knew poetry, practiced calligraphy, understood the meditative aspects of the tea ceremony, could distinguish incense fragrances, and recite classical verses. They wrote letters, kept diaries, had access to literature. At the same time, the average woman in noble Poland was illiterate — not by choice, of course. And not just Polish women — for most women in Europe, taking part in cultural life, let alone expressing themselves in writing, was a luxury beyond reach. In Japan, even a townswoman with no aristocratic lineage could have a cup of sake with a friend in a teahouse, go to the kabuki theater, or try a new dish from a street stall.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Women of the Yakuza – Silently Bearing the Scars on Their Bodies and Hearts

The Female Samurai Unit Jōshitai – The Ultimate Determination of Fighting Mothers and Sisters

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!