The Black Shōgun Before the Age of the Samurai – Tamuramaro

A Shōgun Without the Samurai

And yet today, we pose a different question – one asked more rarely, but just as fascinating: could a shōgun have existed before the samurai? Yes – in a raw, warlike, and… imperial form. Today, we will meet the greatest among them – the Black Shōgun Tamuramaro.

The Yamato Army Prepares for Battle

In the open field, beneath tall poplars and tufts of stunted grass, the Yamato army was gathering – grim, silent, organized in a way that Japan was only just beginning to recognize as modernity. These were not yet the samurai known from later centuries, but the armed extension of imperial will, recruited from southern provinces, from warrior families, from loyal local clans. Their armor was still far from the elegance of the Heian period – simple, functional, heavy with lacquered leather and bronze. In the cold morning light, their keiko-style armor gleamed, laced with fabric cords and reinforced with metal plates.

At the rear – cavalry, the stately tsuwamono (兵, warriors, not yet samurai for several centuries to come). Horses from the provinces of Mutsu and Hitachi, small but enduring. Riders clad in deerskin armor, lacquered black and adorned with simple symbols – a star, a flame, a maple leaf. Each bore a tachi (太刀) – a sword longer than later katana, worn edge-down, suspended from a wide belt. Some carried horagai (法螺貝) conch shells at the saddle, from which they drew sounds that signaled the army – deep, low tones like groans from within the earth. Others struck taiko (太鼓 – “great drums”) – command drums carried on the backs of war servants, pounding rhythmically, like the army’s heartbeat.

At the center of the headquarters fluttered the commander’s military banner – purple silk adorned with golden thread, embroidered with the characters Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍), the title bestowed by the emperor. Though it bore no image of the sun, everyone knew that its authority came from the very descendant of Amaterasu. Around the banner stood a makeshift altar – wooden, provisional, built from pure hinoki wood. A priest in white robes recited ritual norito prayers, beseeching the gods for victory. Incense rose into the air like the spirits of ancestors. The gunji (郡司 – local officials, aristocrats commanding troops from their own provinces) knelt, touching their foreheads to the ground.

And then he appeared.

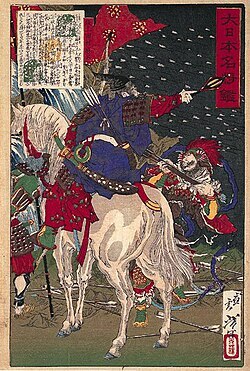

Tamuramaro. The Black Shōgun.

He rode a tall warhorse, its flanks protected by lacquered leather plates, its eyes burning. Tamuramaro’s armor, gleaming with the deep black of lacquer, clung to his body like a second skin. On his shoulders rested a dark, heavy cloak of bear fur – a trophy from one of his northern campaigns, or perhaps just a legend that no one dared question. His helmet, with a wide visor and tall crest, adorned with stylized horn patterns and a bronze grimace, resembled the face of an oni – a demon of the mountains and night. The leather armor plates, stiffened with bronzed metal, gleamed like black mirrors, and at his hip – fastened edge-down – lay a long, curved tachi, ready for the charge. With each step of the horse, the commander’s silk cloak rose and fell heavily, as if the entire unit were bowing to the northern sky.

Tamuramaro said nothing. He rode slowly along the formation, his hand resting on the hilt of his sword, his gaze piercing like a blade. Some foot soldiers lowered their eyes. Others whispered prayers. But soon after – they raised their heads. For his silence was heavier than commands, and his presence was a sign that the emperor truly watched.

— If he stands with us, no darkness can consume us – thought the soldiers, though not one dared utter even a louder breath.

And then – at the signal of the Black Shōgun – the army moved. Quietly, without clamor, like a wave of steel and leather, pushed forward by the hand of the gods into the northern mist.

Who Was Tamuramaro?

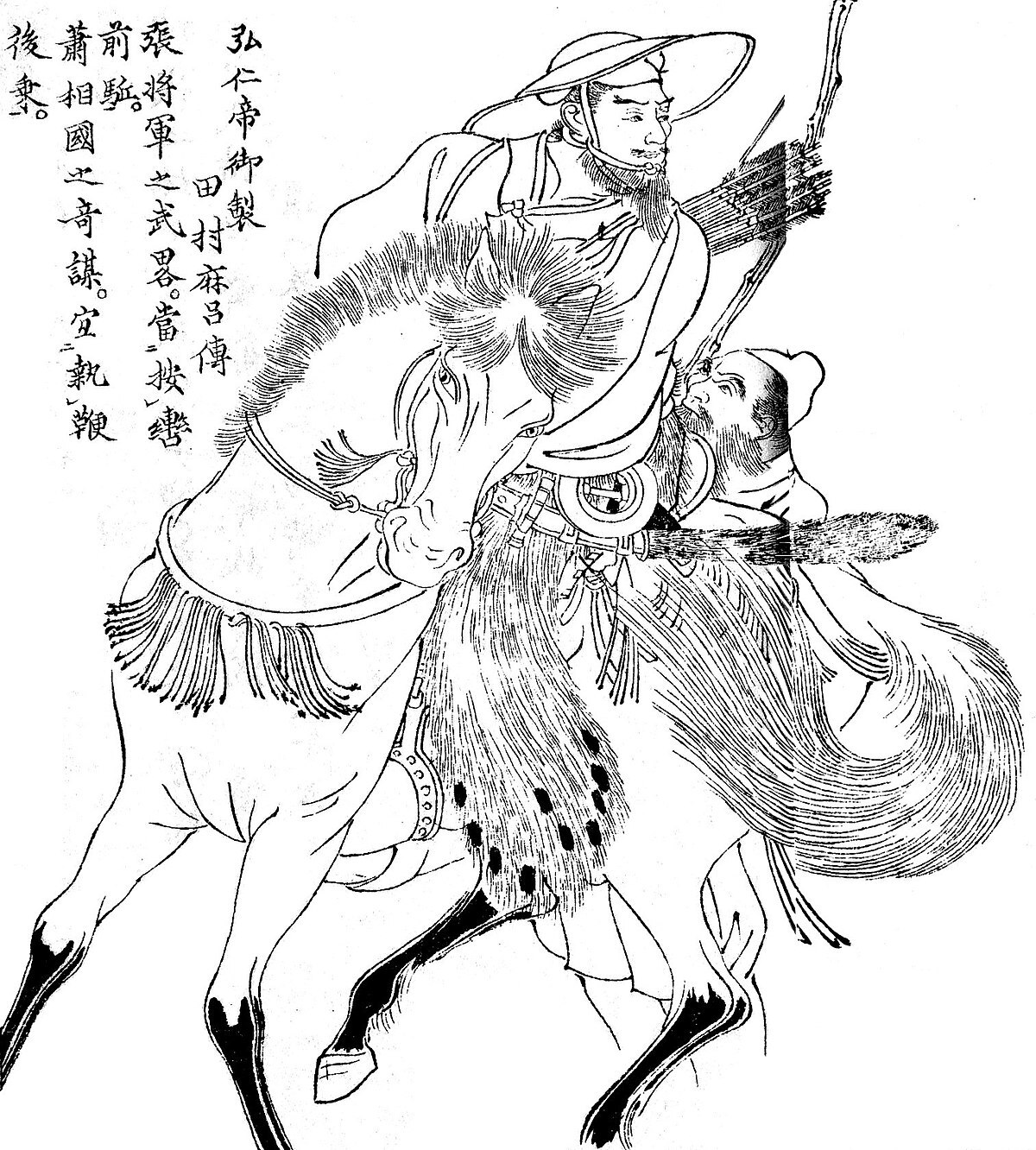

Tamuramaro was a general and official, a loyal servant of Emperor Kanmu. He stood out not only for his military prowess but also for his organizational talent, discipline, and austere ethos. It was he who was entrusted with one of the most remarkable titles in Japanese history—Sei-i Taishōgun (征夷大将軍), which literally means “Great General for the Subjugation of the Barbarians.”

That is precisely why the figure of Tamuramaro—today little known—represents a fascinating shadow of the true beginnings of Japan’s military system, before the samurai ethos emerged, before the bushidō code was solidified in literature, and before the shogunate became the center of real power.

(More on the evolution of the title shōgun—from a commander of imperial campaigns to the supreme military ruler—you can read in my text: What Does “Shōgun” Really Mean? One word that forged the Japan of samurai in steel and blood).

The Life of Sakanoue no Tamuramaro

Origins and Background

Even as a youth, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro distinguished himself at the imperial court not only through impeccable manners but also with a silent discipline and an exceptional memory, which made him a candidate for future administrative responsibilities. He received a classical education—knowledge of Chinese classics, calligraphy, grammar, and ceremonial protocol—but his true talent shone brightest outside the palace walls.

His first military assignments date back to the 770s, when imperial expeditions against the Emishi ended in a series of costly defeats. Previous generals—including Ki no Kosami and Ōtomo no Otomaro—failed to break the resistance in the north. Tamuramaro served alongside them as an auxiliary officer, gaining experience in conducting campaigns in difficult terrain: forests, mountains, and the swamps of Mutsu. He learned the language of the Emishi, studied their tactics, rituals, fortification methods, and ways of life.

In the eyes of Emperor Kanmu, Tamuramaro earned the reputation of a man “hard as iron, silent as stone, but loyal as a pair of komainu (lion-dogs) guarding the temple gate.” When the capital of Heian was founded in 794, and the new era was to begin with the symbolic subjugation of the barbarian north, the choice was obvious. Tamuramaro was to set out not only as a general—but as Sei-i Taishōgun.

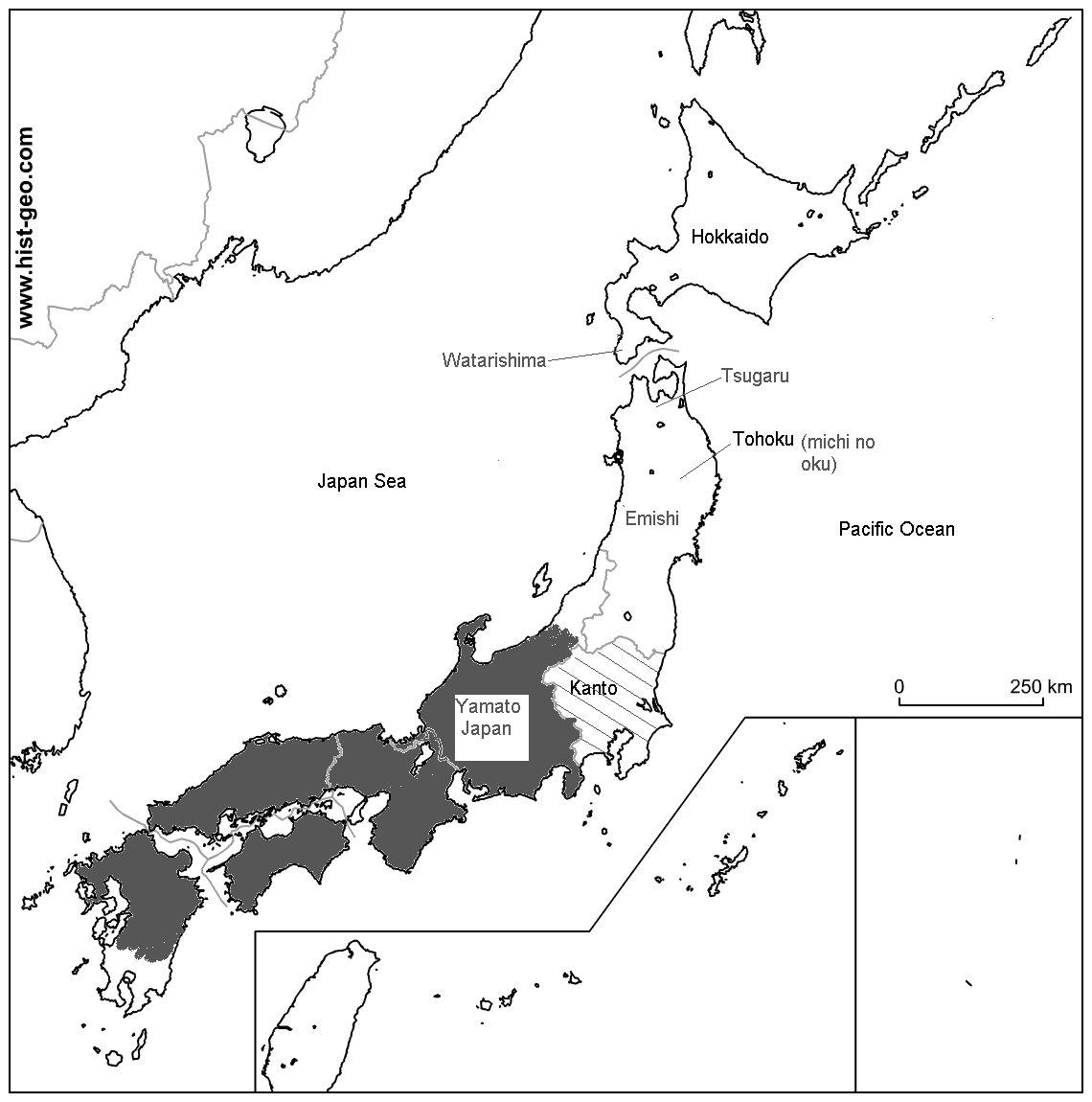

Campaigns Against the Emishi (794–802)

Tamuramaro was sent to complete what others had started and abandoned. From 794 to 802, he led a military campaign intended not only to defeat the Emishi, but to break their spirit and bring the northern lands into the imperial orbit of power. It was no easy task. The terrain was treacherous—marshes, fast-flowing rivers, and forested slopes favored guerrilla raids by local warriors armed with bows and spears. Sometimes the fight was not for a battlefield, but for a bridge, a ford, a narrow mountain pass. Relentless rains, winter snowstorms, and ambushes meant that the imperial army had to learn—to adapt.

Who Stood Against the Imperial Forces?

Two of the most powerful Emishi leaders: Aterui and More. Aterui—sometimes called the “Wild Prince of the North”—was known for his brilliant tactics and mastery of the terrain. He had defeated several expeditions previously sent from Nara and orchestrated a massacre along the Kitakami River. Tamuramaro had to change his approach: he began constructing forts and strongholds, including those in Izawa and Shiwa, which served not only as military bases but also as centers of administration and propaganda. Where the sword could not reach, cunning did—Tamuramaro forged alliances with local Emishi tribes who had already laid down their arms, bribing them with gifts, titles, and intermarriage.

After eight years of war, in 802, Aterui and More—out of courage and resolve, but also in recognition of their inevitable defeat—surrendered their arms and personally submitted to Tamuramaro. The general was moved—he knew the worth of an enemy who had fought with honor and dignity. He sent them to the capital with a plea for clemency. But Nagaoka and Heian-kyō knew no mercy—the Emishi were still, for many, a symbol of rebellion and darkness. Aterui and More were executed, despite Tamuramaro's desperate pleas for their lives. For a commander who believed in the warrior’s honor, it was a deep fracture—a shadow that would never leave him (for more on this event and on the wars between Yamato and the Emishi, see here: Forgotten Wars of Ancient Japan – The Emishi Versus Yamato).

But politics knows only victors. Tamuramaro’s success was undeniable. Japan expanded its borders, the Emishi were pushed into the shadows of history, and the empire triumphed. In the eyes of the court, Tamuramaro became the embodiment of effectiveness—a silent yet ruthless instrument in the hands of the throne.

The Shadow of Power – His Role After the Campaigns

As a reward, Tamuramaro was granted titles reserved for only the highest officials. Dainagon—Grand Counselor, and later Hyōbu-kyō—Minister of War. Yet his actions revealed a growing reserve—as if the shadow of Aterui, condemned to death by the executioner of Yamato despite the Black Shōgun’s promise, still loomed behind him.

He died in the year 811, at the age of 53. He was buried on a hill at the eastern edge of Heian-kyō. It was there, according to legend, that Shōgun-zuka (将軍塚) was erected—a symbolic tomb and monument from which Tamuramaro’s spirit was said to watch over the capital and guard its fate. The place remains a site of pilgrimage to this day.

In the centuries that followed, as memory merged with legend, Tamuramaro began to be venerated as a guardian spirit of warriors, a patron of victory and prudence. He never sat on a throne, never founded a dynasty—but became a model for those who came after: for the Minamoto, the Ashikaga, and the Tokugawa. The quiet, black shōgun from before the samurai era—a man who served in the shadow of the throne but became a legend himself.

New Legends of an Ancient Shōgun

In the context of 20th-century historiography, however, radically different interpretations emerged, moving beyond aesthetic and symbolic frameworks. Some thinkers associated with the Afrocentric movement—such as W.E.B. DuBois, Joel A. Rogers, Runoko Rashidi, and Basil Hall Chamberlain (though his approach was more philological than Afrocentric)—began to speculate that Tamuramaro might have been Black or of African descent. These theories, however, are not based on Japanese sources but on speculative interpretations of iconography, place names, oral legends, and alleged connections between Japan and ancient Africa or the Middle East.

In reality, no Japanese sources from the Nara or Heian periods suggest African ancestry for Tamuramaro, nor do they mention the color of his skin. Chronicles such as the Shoku Nihongi or Nihon Kōki describe him solely in administrative, military, and ritual contexts. The very term “Black Shōgun” appears only in folklore and literature of later eras, most likely as a reference to his black armor and role as the “silent executor” of imperial will. In Japanese culture, black carried many meanings—from elegance to threat—but it was not associated with race. Moreover, there is no confirmed evidence of the presence of people of African descent in Japan during the Heian period.

So why did such interpretations arise—and gain a certain popularity in some circles? History, like any cultural narrative, is sensitive to the identity needs and political climates of successive eras. Afrocentric readings of Tamuramaro’s story tell us less about him than about the desire to find Black heroes in global historical narratives. In the face of marginalization and silence in a history dominated by Western perspectives, Afrocentric movements sought—and still seek—figures who could symbolize the presence of Africans even in distant cultural spheres such as Japan.

The Legacy of Tamuramaro

Tamuramaro did not found a warrior clan of his own, did not seek power over Japan, and did not establish a bakufu. He was a general in the service of the emperor—a man of an era that still believed in the undivided sovereignty of the court in Heian-kyō. Unlike Yoritomo or Tokugawa, his power did not stem from actual territorial control but from imperial mandate. He was a blade held in the sovereign’s hand—and he never left that hand.

And yet it was he who blazed the trail for those who would come after. In command structures, in armor iconography, in battle rituals and strategies, Tamuramaro was a harbinger of the world that was yet to be born. His figure appears later in epic literature, in war legends, in Buddhist temples as a protective deity, among paintings and stone tablets commemorating ancient heroes. He is a hero without an epic of his own, yet a patron of Japan’s rulers across several eras.

Let him not remain in our memory merely as the mythical “Black Shōgun” of ancient legends. Let him be remembered for what he truly was: an outstanding and exceptionally well-organized commander, whose sword was not yet that of a samurai—but was already cutting across the horizon of the future.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Daily Life in the Ainu Village of Shiraoi on Hokkaido – Tales by the Iworu Fire

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!