Rent-a-Sister: A Japanese Method for Handling Extreme Isolation

RENT-A-SISTER

Contemporary Japan faces several challenges that are both typical for the country and exotic to the rest of the world. Even though these phenomena occur in other countries and cultures, they often take on their most extreme forms in Japan. One such phenomenon linked to the unique aspects of Japanese society—though it also exists elsewhere—is hikikomori.

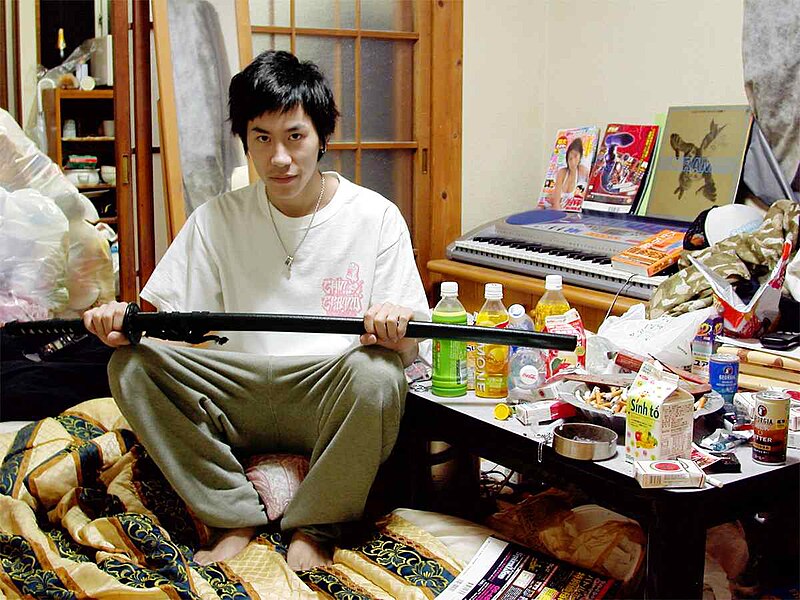

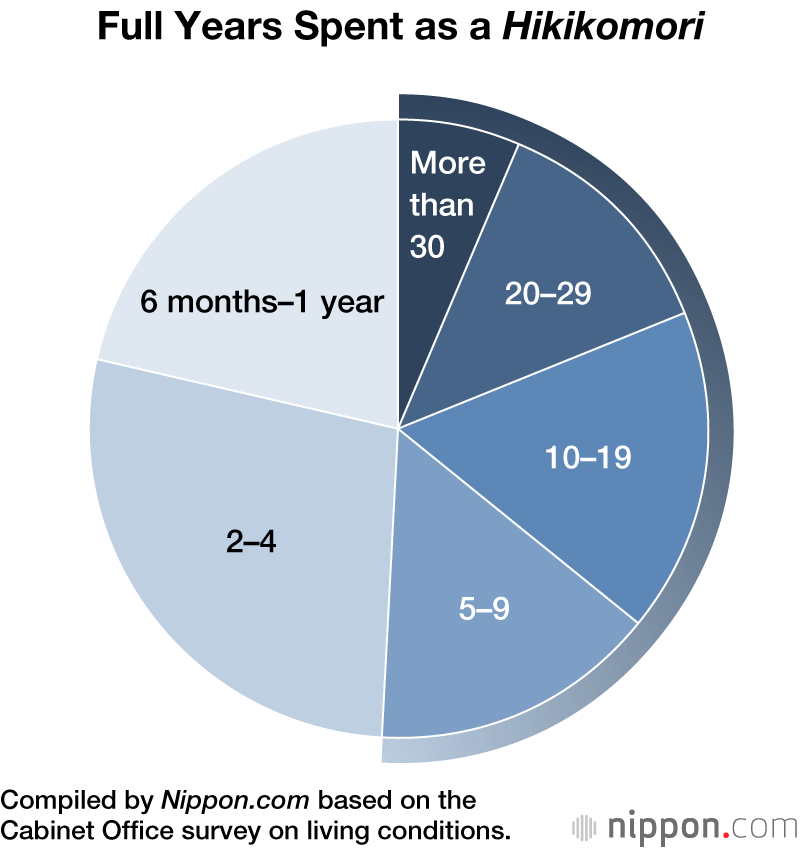

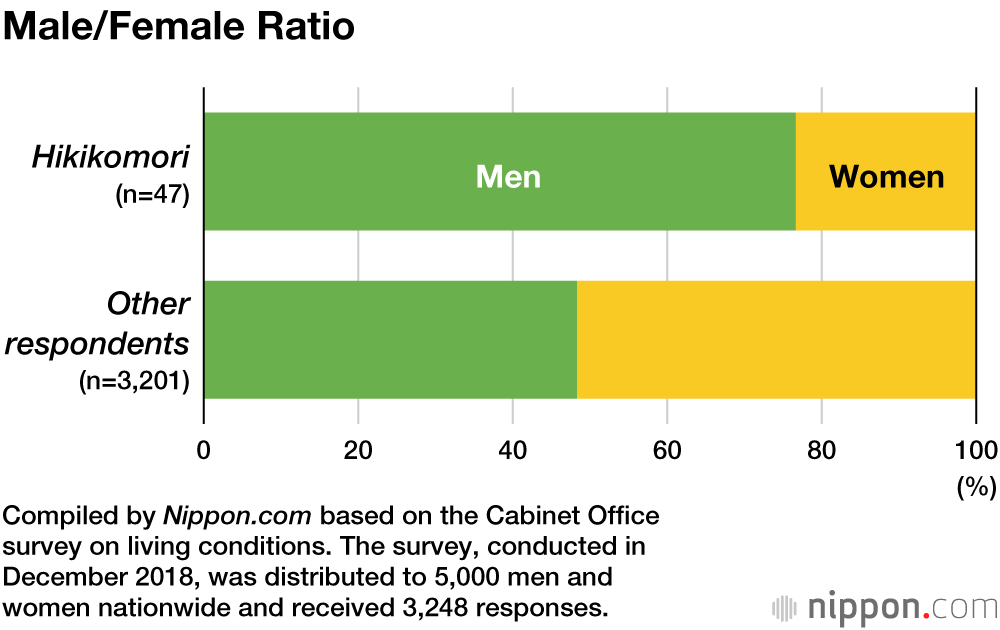

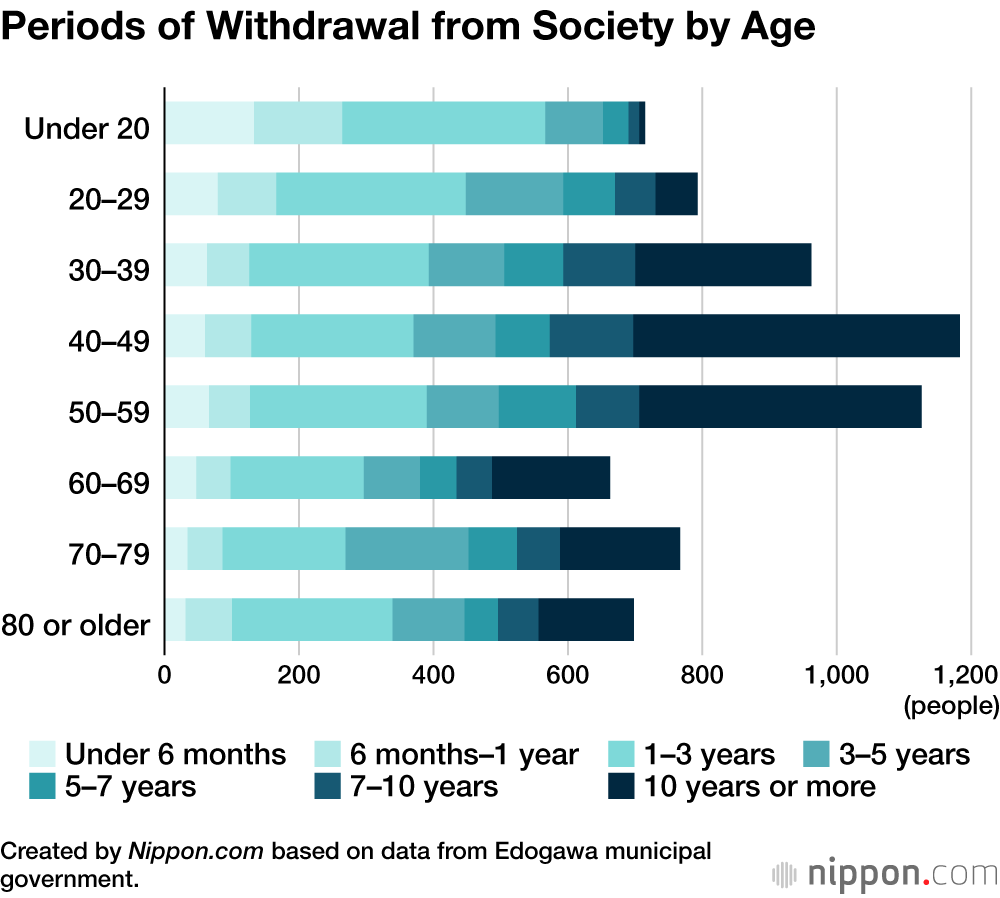

In Japanese society, 1% of the population is missing. They do not leave their homes and fulfill no social role. These are the hikikomori—people who have withdrawn from active social life, suffering from a state of profound social isolation. People who retreat for months or even years (decades, or the rest of their lives) from all forms of social interaction, ceasing to leave their homes. According to recent estimates, this could involve even up to a million Japanese.

In today's article, we will examine how this service works exactly, what its effects are, and what the business and pop culture have to say about it. But first, let's meet Eri – we will accompany her during one of her days at work as a Rental Sister.

A Day in the Life of a Rental Sister

Sendai

Sendai

Meet Eri, a 26-year-old intelligent and somewhat talkative woman for a Japanese, fresh out of psychology at Tohoku University in Sendai. After graduating, she decided to take on a job that could bring about real change in people's lives – she became a rental sister. This choice was driven by her passion for helping others and belief in the possibility of breaking down the social barriers that often isolate individuals with hikikomori from the rest of society. Honestly, it's a great way to gain experience for someone fresh out of school.

Dawn has not yet broken when Eri, a rental sister from the New Start program, is already preparing for a challenging day. Eri, with over a year of experience working with hikikomori, starts her day by reviewing her schedule of appointments. Today her main task is visiting Y.S., a 28-year-old man who has not left his room for several years.

Yuu

Yuu

Before leaving home, Eri prepares a package with Y.S.'s favorite snacks and a new board game featuring themes from the anime "Isekai Ojisan," which may encourage him to interact. Before she reaches the meeting place, she checks her notes from previous visits to ensure she hasn’t overlooked any important details about Y.S.'s progress in treatment.

Everything is important – the tone of voice, the words used, facial expressions. If Eri reacts too intensely or too vividly, she will frighten the patient and he will retreat back into himself. If she is too reserved, the patient may think he has offended her and he will also withdraw into himself. Preparing to talk to a hikikomori is like "warming up before a challenging shogi match. Although no, it's not like chess, it's more like walking through a minefield," says Eri.

- "Yuu-kun, ohayō! It’s me again, Eri. Onii-chan, I brought something you might like," says Eri, using a more casual and close greeting and the warm term "Onii-chan," which means "older brother" in Japanese. This manner of addressing highlights her role as someone close and trustworthy, gradually yielding positive results in her interactions with Yuu.

Artist

Takumi

When Eri arrives, they greet each other briefly, and then they proceed to prepare a meal together, which serves as a form of therapy for Takumi. Today, they decide to make yakisoba, a popular Japanese dish consisting of fried noodles, vegetables, and pieces of pork, all of which are easy to prepare and allow them to focus on conversation. As they prepare the ingredients, Eri talks with Takumi about various spices and their influence on the flavor of dishes.

- "Takumi-kun, maybe after lunch we could go for a short walk? I heard they have those new matcha ice creams on sale that you were talking about last time." Takumi dismisses the suggestion with a nervous laugh, but the seed is planted.

When the food is ready, they take their places at the table in the brightly lit part of the kitchen. The meal proceeds in a pleasant atmosphere, and the conversation flows more freely than usual. Takumi, though still somewhat shy, seems more open to dialogue, which is an important step in his therapy.

After the meal, still sitting at the table with finished plates in front of them, Eri gently brings up the topic of the walk again.

Unfortunately, Takumi gets up abruptly and starts apologizing to Eri while pointing her towards the exit. She didn't understand much of what Takumi muttered among his apologies, but he seemed to say that his favorite anime series was about to start. She scared him. "Well, maybe next time," she thinks to herself as she gets ready to leave.

Ending the day with Takumi reaffirms for Eri that patience and understanding in dealing with hikikomori are the number one traits to cultivate if one wants to see results. A first outing would be a significant achievement, but it was not yet time. Their delicate and complex situation requires Eri not only to be professional but also to have immense empathy and the ability to build trust, along with vast reserves of patience.

Evening

As Eri returns home, she reflects on her interactions of the day. She is already planning what and how to prepare for tomorrow's visits. Who to talk to and about what. Towards whom she should take a step forward and encourage a deepening of the relationship, and towards whom she must still maintain a semi-formal stance and distance.

A day in the life of a rental sister is full of challenges but also immense satisfaction from every, even the smallest, progress of her charges. Eri, like other rental sisters, plays an important role in combating the hikikomori problem every day, changing the lives of many people. "When I saw how A.M., when we first went outside after years of isolation, looked around fascinated by the trees in the park and took a deeper breath of fresh air, I had tears in my eyes…" Eri concludes, responding to what this job gives her.

Hikikomori - Who Are They?

The Meaning of "Hikikomori" (引き籠もり)

The Meaning of "Hikikomori" (引き籠もり)

The term "hikikomori" comes from the Japanese language, where "hiki" (引き) means "to pull" (more in the sense of "pulling away"), and "komori" (籠もり) means "to seclude oneself." Thus, the word can literally be interpreted as "secluding oneself" or "withdrawing." In a social context, hikikomori describes individuals who isolate themselves from society, spending most or all of their time in their rooms and avoiding direct contact with other people. It is a phenomenon primarily visible in Japan but is becoming increasingly recognized worldwide.

Related Concepts, e.g., NEET (ニート) and Otaku (オタク)

An acronym for "Not in Education, Employment, or Training," NEET describes someone who is not engaged in education, work, or training. In Japan, this term is often associated with hikikomori, but the difference is that NEET can be socially active, whereas hikikomori avoid all forms of social participation. NEET could well be a "party-goer" living off their parents. They don't go to school, don't work, but lead an active social life. Of course, people with hikikomori syndrome are also often (but not always) NEETs (by secluding themselves in their homes and not forming any relationships with people outside, they often do not work or study).

This term is used to describe someone with obsessive interests, usually related to manga, anime, or video games. Although otaku can spend a lot of time in isolation similar to hikikomori, the main difference is their engagement in specific subcultures and communities. They don’t have to be "hermits;" they can very well work or study. The main determinant here is their hobby. A slice of reality to which they dedicate a large part of their life (it could be Dragon Ball, Naruto manga, but it can also be non-Japanese things, like Star Trek).

We discuss the phenomenon of hikikomori more extensively here: hikikomori, so I refer interested readers there. However, in this article, we will focus not on the causes and functioning of hikikomori but on the titular sisters.

Rental Sisters

Who Are They?

Who Are They?

The "rental sister" service in Japan has been designed as a creative solution to the hikikomori problem, offering personal and direct support to individuals isolating themselves from society. Rental sisters fulfill various roles aimed at supporting their clients both emotionally and socially.

Companionship and emotional support

Support in handling daily matters

Support in handling daily matters

Helping with organizing household duties, motivating to leave the house for necessary errands, or accompanying during outings, which is especially important for people who have not left their homes for a long time.

Supporting personal development

Encouraging the development of social and personal skills such as communication or time management. Sisters often also act as informal coaches, supporting their clients in setting and achieving personal goals.

Statistics and Research - Evidence of Service Effectiveness

Although there are no widely available statistical data that quantitatively measure the effectiveness of the "rental sister" service, available sources and reports from programs like New Start provide valuable insight into the potential benefits of this form of intervention. The New Start program, founded in 1994 in Japan, is an initiative aimed at helping people suffering from hikikomori reintegrate into society through offering residential therapeutic programs, employment support, and social activities. The New Start program has recorded several successes that shed light on the possibilities for reintegrating people suffering from hikikomori.

Successes of the New Start Program

Successes of the New Start Program

Between 2017 and 2019, the New Start dormitory helped about 2,000 hikikomori, of which 80% were able to achieve independence after more than a year of stay. This program offers structural support through part-time work and volunteerism, which facilitates the gradual reintegration of participants back into society.

Individual Cases

About individual cases (of course, actual surnames are not given), one can read in the reports of programs such as New Start., which boast stories such as the story of a certain Ikuo.

This story, ended with a happy ending in the form of his marriage to Ayako, is an example of how well the New Start program can work. Unfortunately, we do not know the stories of people for whom the program did not work, nor what the percentage of effectiveness is.

Challenges in the Reintegration Process

Challenges in the Reintegration Process

Despite positive stories, the reintegration of hikikomori into society remains a challenge. Many hikikomori resist interactions, which primarily means that the reintegration process is often lengthy. It may require months or even years of regular meetings and consistent presence of a rental sister before a person with hikikomori decides to take bigger steps, such as going to the park or cinema.

Besides direct support, the presence and activities of rental sisters also help change the societal perception of the hikikomori phenomenon. Through education and public discussions, society begins to view hikikomori not as a result of laziness or oddity but as a serious and complex social issue.

The Importance of Social Support

The Importance of Social Support

Research shows that social support and support networks are crucial in treating conditions like hikikomori, akin to the treatment of alcoholism. Programs such as New Start integrate these elements through support groups and group therapies. These become a key factor in reintegrating hikikomori back into society right after rental sisters (without whom hikikomori would not agree to participate in group therapy or even stay in the same room with a group).

Rental Sisters as Ambassadors of Hikikomori in Society

Rental Sisters as Ambassadors of Hikikomori in Society

Stereotypes vs. Reality of Hikikomori

Social stigma and misunderstanding of the hikikomori issue can result in the application of inappropriate intervention methods. Misconceptions of hikikomori as lazy or eccentric can lead parents to drastic actions, unfortunately misdirected. In Japan, it is evident that parents are determined to forcibly extract their children from their isolation, which can lead to an escalation of conflict and violence.

The Educational Role of Rental Sisters

The Educational Role of Rental Sisters

Programs like "Rental Sister" play a crucial role in changing the way society perceives hikikomori. Rental sisters, acting as ambassadors and educators, help in spreading accurate knowledge about hikikomori. Through their work, which aims not only to support individuals but also to educate families and local communities, they contribute to reducing the stigmatization of this phenomenon.

The Case of Fujisato

In Fujisato, actions for hikikomori began in 2010, and since then, significant successes have been noted. Over five years since the start of the support projects, 86 out of 113 identified hikikomori managed to achieve independence and reintegrate into society.

Every two to three months, hikikomori are visited in their homes, receiving newsletters with information about available support and events in the town. These actions gradually convince hikikomori to try engaging in social life, often resulting in success.

These focused and effective actions in Fujisato show how social engagement and appropriate strategies can contribute to a noticeable improvement in the hikikomori problem.

How We See Hikikomori and Rental Sisters in Pop Culture?

"Welcome to the N.H.K." (NHK ni Youkoso! – manga and anime)

Author: Tatsuhiko Takimoto, year: 2006

Misaki Nakahara plays the role of a "rental sister," although her relationship with Satou is more complex and full of tensions. The "contract" she proposes aims to help Satou overcome his hikikomori through regular meetings and therapeutic sessions. Misaki gradually reveals her background and motivations, allowing an understanding of why she is so eager to help Satou.

Misaki's role in Satou's life develops gradually. Initially a mystery to him, as the story unfolds, she becomes an important support, freeing him from his own inner demons and limiting beliefs. Their interactions lead to a series of challenges that force Satou to confront external reality, which is a key moment in his struggle with isolation.

"Recovery of an MMO Junkie" (Netojuu no Susume – manga/anime)

"Recovery of an MMO Junkie" (Netojuu no Susume – manga/anime)

Author: Rin Kokuyou, year: 2017

"Recovery of an MMO Junkie" is a story about Morioka Moriko, a 30-year-old hikikomori who quit her corporate life to immerse herself in the virtual world of MMO games. Moriko, as a fervent gamer, finds new life in the game, which is vastly different from her real, isolated existence. The story focuses on her daily interactions in the game and her gradual realization that real life may offer more than what the virtual world provides.

The role of social support is subtly outlined by the characters Moriko meets online, especially one player who turns out to be a colleague from her former job. These online interactions become the bridge that helps Moriko gradually return to society. This character, though not formally a "rental sister" (perhaps more of a brother), serves a similar role of support and motivation for Moriko.

The climactic moment of the series is when Moriko decides to meet her game friends in the real world. This change of scenery reflects a deeper transformation in her life, showing how healthy relationships built in the virtual world can contribute to a real change in the life of someone struggling with social isolation.

"Colorful" (Karafuru – anime film)

"Colorful" (Karafuru – anime film)

Director: Keiichi Hara, year: 2010

"Colorful" is an anime film that tells the story of a soul that gets a second chance at life in the body of Makoto, a 14-year-old boy who was close to becoming a hikikomori. The film delves into the causes of Makoto's depression and withdrawal from social life, including family issues and peer pressure. "Colorful" addresses themes of redemption and the importance of understanding and support in overcoming personal demons.

Makoto receives support from various characters he encounters in his new chance at life; these characters play the role that rental sisters do in reality. These interactions teach him the importance of valuing his life and how big a role understanding and empathy can play in improving it.

The decisive moment of the film is when Makoto, supported by newly met friends and finding support in his family, begins to appreciate each day and opens up to new experiences. By accepting help, he gradually breaks down his own barriers, learning acceptance and finding meaning in life.

New Perspectives

New Perspectives

Initiatives like New Start are becoming key elements in Japan's fight against social isolation, especially in the context of the hikikomori phenomenon. While direct statistics on the effectiveness of these programs are limited, there is evidence suggesting that regular interventions can significantly improve the quality of life for those affected by this issue.

New Start is continually evolving. In recent years, it has expanded its activities to include organizing summer reintegration camps where hikikomori have the opportunity to meet and work together on group projects, often resulting in positive outcomes in building their confidence and social skills.

As society becomes increasingly aware of mental health issues and social isolation, initiatives like Rent-a-Sister may become even more integrated into the mainstream of health and social care. The Japanese government has already started pilot programs aimed at integrating such services into the traditional social care system, hoping to expand their availability and improve efficacy. It is clear that although the road to completely eliminating the hikikomori issue is still long, innovative approaches like rental sisters play a key role in changing how Japan handles this complex social problem. By developing these programs and learning from experiences, future generations can expect to have better tools to deal with social isolation and its consequences.

>> SEE ALSO SIMILAR ARTICLES:

Beyond Stereotypes: The True Face of Hikikomori in Japan and Worldwide

Johatsu – on average, every year over 80,000 Japanese people disappear. They call it 'evaporating.'

The Aokigahara Suicide Forest: What Secrets Do the Silent Trees Guard?

Parasite Singles: Japan's Demographic Dilemma at the Heart of Family

"Strong Japanese Women"

see book by the author

of the page

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

未開 ソビエライ

An enthusiast of Asian culture with a deep appreciation for the diverse philosophies of the world. By education, a psychologist and philologist specializing in Korean studies. At heart, a programmer (primarily for Android) and a passionate technology enthusiast, as well as a practitioner of Zen and mono no aware. In moments of tranquility, adheres to a disciplined lifestyle, firmly believing that perseverance, continuous personal growth, and dedication to one's passions are the wisest paths in life. Author of the book "Strong Women of Japan" (>>see more)

Personal motto:

"The most powerful force in the universe is compound interest." - Albert Einstein (probably)

Mike Soray

(aka Michał Sobieraj)

Write us...

Ciechanów, Polska

dr.imyon@gmail.com

___________________

inari.smart

Would you like to share your thoughts or feedback about our website or app? Leave us a message, and we’ll get back to you quickly. We value your perspective!

Sendai

Sendai Yuu

Yuu

The Meaning of "Hikikomori" (引き籠もり)

The Meaning of "Hikikomori" (引き籠もり) Who Are They?

Who Are They? Support in handling daily matters

Support in handling daily matters Successes of the New Start Program

Successes of the New Start Program Challenges in the Reintegration Process

Challenges in the Reintegration Process The Importance of Social Support

The Importance of Social Support Rental Sisters as Ambassadors of Hikikomori in Society

Rental Sisters as Ambassadors of Hikikomori in Society The Educational Role of Rental Sisters

The Educational Role of Rental Sisters "Recovery of an MMO Junkie" (Netojuu no Susume – manga/anime)

"Recovery of an MMO Junkie" (Netojuu no Susume – manga/anime) "Colorful" (Karafuru – anime film)

"Colorful" (Karafuru – anime film) New Perspectives

New Perspectives